This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth has published this week and the second is work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

There’s been quite a bit of conversation about the influence and scope of the so-called gig economy in the overall U.S. economy. Some observers think the “sharing economy” companies are the harbingers of a new labor market, while others think the hype is nothing more than sound and fury. New data shows the rise in independent contractors predates the rise of Uber and its ilk.

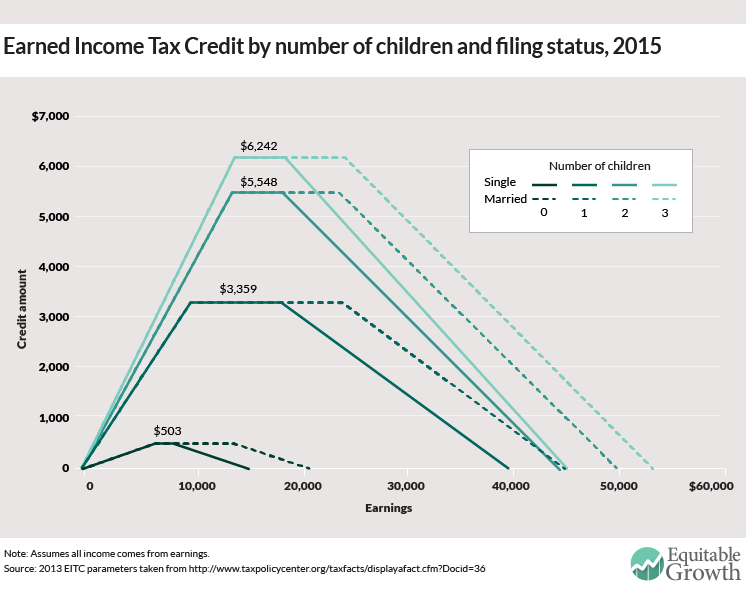

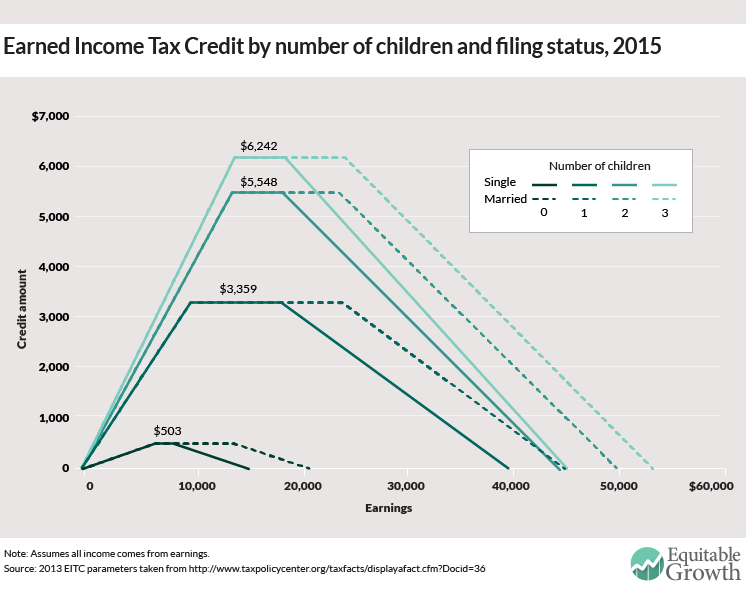

The Earned Income Tax Credit has been very successful at reducing poverty in the United States, and policymakers are thinking of ways to expand upon it. One such proposal is to expand the size of benefits for childless workers. We might want to also think about policies that are complementary to the tax credit.

Speaking of the Earned Income Tax Credit, University of California, Berkeley economist Jesse Rothstein summarizes the research on the tax credit in a new issue brief.

The Federal Reserve raised interest rates this week for the first time in almost a decade, ending the era of zero-interest-rate policy. At least for now. But with U.S. employment growth barely keeping up with the country’s population growth, the Fed’s decision was wrong.

The way the Fed hiked the federal funds rate was a first for the central bank. The use of the reverse repo market reflects big changes in the financial system, including the rise of the shadow banking system. And the rise of that system is a sign of a changing global economy.

Links from around the web

History may not repeat itself, but sometimes it does rhyme. Matthew C. Klein looks at the parallels between the economy of today and the economy in 1998 when a decision about interest rates also sparked considerable debate. Klein argues the Fed might be “atoning” for their easing almost 20 years ago. [ft alphaville]

The high level of economic inequality in the United States is often reproduced in other ways, including in family life. Economic circumstances have a deep impact on how families function—particularly on how parents raise their children. Claire Cain Miller takes a look at the evolution of parenting inequality in the United States. [the upshot]

While U.S. wage growth has been decidedly mediocre recently, data on incomes have shown a much better trend. But that difference might be because the data isn’t up to date. Justin Lahart points to the new release of data from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages as possibly confirming that idea. [wsj]

In the United States, benefits such as health insurance and retirement savings plans are tightly connected to employment. For the most part, they’re provided through your employer. But it doesn’t have to be that way. Shane Ferro reports on a conference about the future of benefits in a new world of work. [huff post]

An argument being banded about recently is that global demographic changes will soon shift bargaining power back toward labor and help boost wage growth in high-income countries. But how large will this effect be in the face of different institutions across countries? Duncan Weldon, formerly of the BBC, looks into this question. [medium]

Friday figure

Figure from “The Earned Income Tax Credit” by Jesse Rothstein.