With the rise of new internet-based companies and the smartphone as an essential part of many people’s lives, it can be hard to believe that the U.S. economy is lacking for innovation and productivity enhancement. But that’s exactly what research on the state of U.S. productivity growth says. After a period of strong growth during the late 1990s and the early 2000s, U.S. productivity growth has slowed since 2004.

This apparent decline in the face of seeming technological bounty has caused some economists and analysts to wonder if the productivity statistics are accurately capturing the gains from new technology. In other words, our measures of economic output—and therefore productivity—may be understating reality. A new working paper, however, throws some cold water on that argument.

The mismeasurement explanation for the slowdown in productivity growth can be summarized as such: Many of the technological advances of the last decade are seemingly free to consumers as they don’t have to directly pay for the service. Google, for example, can greatly enhance one’s productivity, although there’s no fee to use it. The rise of these “free” internet services understates the output growth of the U.S. economy and therefore productivity growth.

On its face, this argument makes sense. But a look at the data, such as this analysis by economist Chad Syverson of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, shows how implausible it is that mismeasurement can explain the vast majority of the decline in productivity growth. Syverson takes four cuts at the data and finds the mismeasurement story lacking.

First, the United States isn’t the only country where productivity growth has declined. In fact, it’s declined in pretty much every country that’s a member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, whose membership is usually a sign of a high-income economy. But there’s quite a bit of variation in the extent to which those countries produce and consume the information and communications technologies at the heart of the supposed mismeasurement. If traditional measures weren’t capturing the gains of these technologies, we’d expect countries with higher levels of ICT production and consumption to have productivity drop more. But that’s not what Syverson finds; instead, he finds that there’s no relationship at all between the two.

Second, there’s already research on the extent to which the internet and related technology has given consumers added utility, increasing what economists call “consumer surplus.” As Syverson shows, even the largest of these estimates can only explain a third of the supposed gap in output from mismeasurement. Furthermore, all this consumer surplus would have to not be included in the price of things like broadband internet services. This seems unlikely.

The third test Syverson runs is to look at the specific sectors’ contributions to the overall U.S. economy—their value added—to see how much larger they would have to be for the mismeasurement story to make sense. For mismeasurement to explain even a third of the hypothesized output gap, the value added of internet-related industries would have needed to increase by 170 percent from 2004 to 2015, which is three times the actual growth rate.

Finally, Syverson looks at the difference between U.S. gross domestic product and gross domestic income. Both are measurements of economic output that should be the same in theory but come from different data sources—GDP is based on expenditure and GDI on income. For the last several years, GDI has been higher than GDP. The difference between the two may be an indication that GDP isn’t capturing technological gains. But the difference started in 1998 during an increase in productivity growth, and most of the difference is due to higher payments to capital.

It’d be nice if the recent spate of internet-related advances could rescue the U.S. economy from a low-growth future in deus ex machina fashion. But that just doesn’t seem to be the case. Instead, we need to hunker down and really think through the sources of innovation and productivity growth.

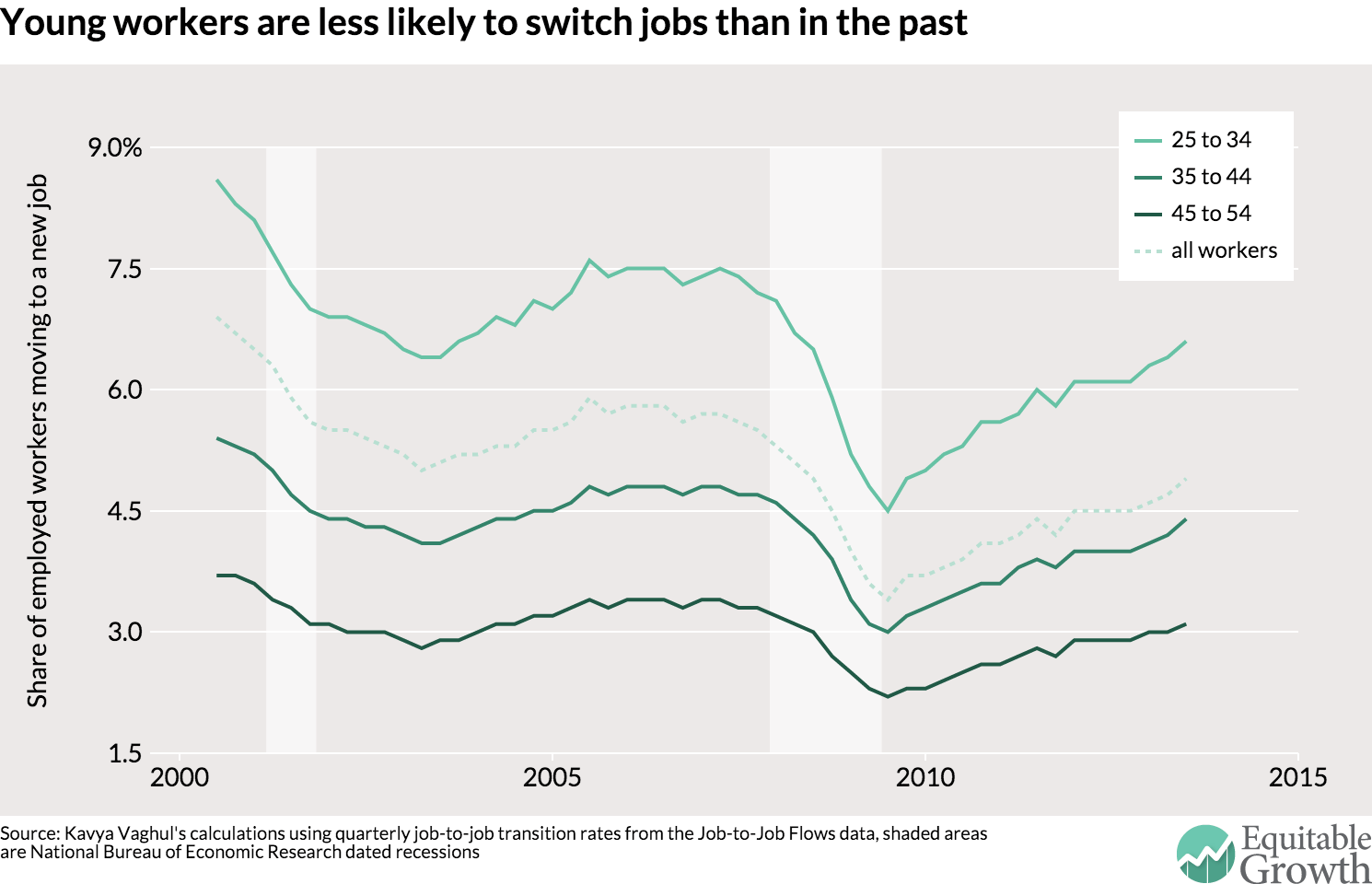

Since 2000, the job-to-job transition rate for all U.S. workers has been on the decline. From the peak of the overall transition rate in the third quarter of 2000 to the third quarter of 2013, the rate for workers ages 25 to 34 declined by about 23 percent. Over that same period, the switching rate fell by 18 percent for workers ages 35 to 44, and by 16 percent for workers ages 45 to 54. The decline has been the largest the youngest workers.

Since 2000, the job-to-job transition rate for all U.S. workers has been on the decline. From the peak of the overall transition rate in the third quarter of 2000 to the third quarter of 2013, the rate for workers ages 25 to 34 declined by about 23 percent. Over that same period, the switching rate fell by 18 percent for workers ages 35 to 44, and by 16 percent for workers ages 45 to 54. The decline has been the largest the youngest workers.