- : About Us | Authors Alliance

- : Why Is the CBO Concocting a Phony Debt Crisis?

- : Still Crazy After All These Years

- : Preparing for the Next Recession: Lessons from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act

Category: Equitablog

Weekend reading: Hysteresis, wage setting, market concentration, and more

This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth has published this week and the second is work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

After recessions, there’s usually quite a bit of geographic variation in employment rates. Some areas of the country are hit much worse by a recession than others, but eventually those differences erode. But that hasn’t happened in the wake of the Great Recession—and a new paper says it might not happen until 2021.

The role of firms in income inequality is an increasingly popular topic of conversation for researchers and analysts. But sometimes those conversations conflate two different trends that result in firms paying more on average than other firms. Untangling the two has important ramifications for how we understand the labor market.

Tax credits have become some of the more popular policy interventions when it comes to improving the living standards of workers at the lower end of the wage distribution. While programs like the Earned Income Tax Credit have been quite successful, they certainly can be improved, as new research shows.

As the global economy seems to weaken, investors complain about the communications strategy of the Federal Reserve, and commentators ponder the usefulness of policies once deemed radical, a debate about the proper tools of monetary policy is raging. But maybe it’s time to expand that conversation even further.

Links from around the web

The last two decades have seen high levels of corporate profits, an increasing return to capital, and high levels of market concentration in the United States. In other words, the U.S. economy has a competition problem. The Economist details the extent of this problem. [the economist]

Despite continued gains, there’s still a significant gap between the earnings of men and women in the United States. While there are a number of reasons for that gap, a major cause is occupational segregation. Claire Cain Miller digs into new research on the topic. [the upshot]

The research Miller cites is an example of work that takes into account the role of gender and identity when it comes to economic matters. As Martin Sandbu argues, ignoring the role of gender can lead to economic analysis that misses major trends and significant issues. [free lunch]

“We’re out of the frying pan of speculative excess and into a subtler and more insidious problem of chronic undersupply.” Matt Yglesias details the next housing crisis the U.S. economy is facing. [vox]

Over the past four years, members of the Federal Open Markets Committee—the Federal Reserve’s policymaking arm—have been steadily lowering their estimate of “longer-run” interest rates. Matthew C. Klein notes that this indicates the central bank is starting to come to grips with the idea of secular stagnation. [ft alphaville]

Friday figure

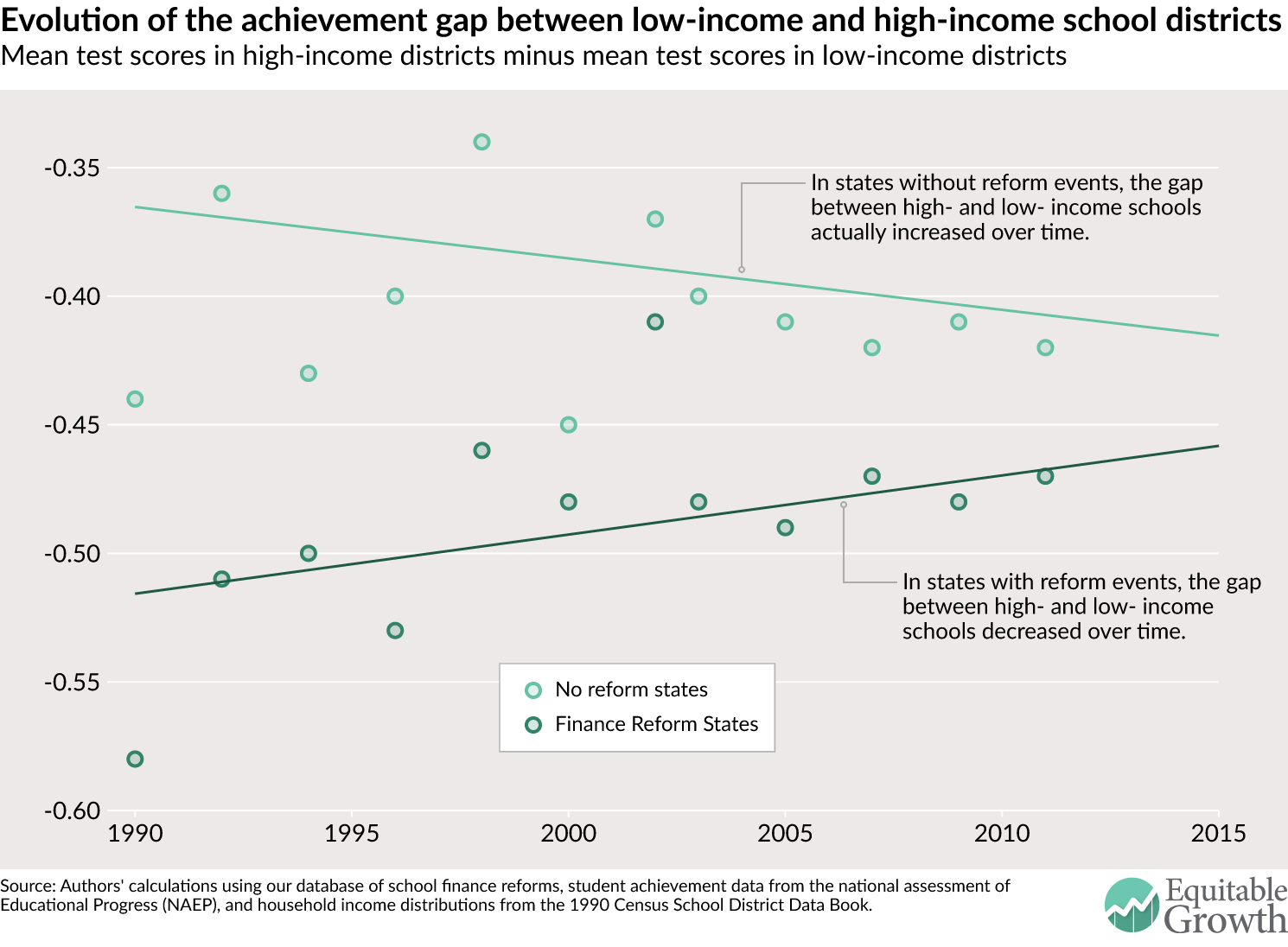

Figure from “Can school finance reforms improve student achievement?” by Julien Lafortune, Jesse Rothstein, and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach.

Must-Read: Pam Samuelson et al.: About Us | Authors Alliance

Must-Read: A very worthy endeavor.

However, I feel like a gotta say here that Google Books was the best vehicle for them to realize their dreams.

What is the current state of Google Books, anyway?

: About Us | Authors Alliance: “Authors Alliance promotes authorship for the public good…

… by supporting authors who write to be read. We embrace the unprecedented potential digital networks have for the creation and distribution of knowledge and culture. We represent the interests of authors who want to harness this potential to share their creations more broadly in order to serve the public good. Unfortunately, authors face many barriers that prevent the full realization of this potential to enhance public access to knowledge and creativity. Authors who are eager to share their existing works may discover that those works are out of print, un-digitized, and subject to copyrights signed away long before the digital age. Authors who are eager to share new works may feel torn between publication outlets that maximize public access and others that restrict access but provide important value in terms of peer review, prestige, or monetary reward. Authors may also struggle to understand how to navigate fair use and the rights clearance process in order to lawfully build on existing works.

The mission of Authors Alliance is to further the public interest in facilitating widespread access to works of authorship by assisting and representing authors who want to disseminate knowledge and products of the imagination broadly. We provide information and tools designed to help authors better understand and manage key legal, technological, and institutional aspects of authorship in the digital age. We are also a voice for authors in discussions about public and institutional policies that might promote or inhibit the broad dissemination they seek.

Must-read: Avi Rabin-Havt: “Why Is the CBO Concocting a Phony Debt Crisis?”

Must-Read: : Why Is the CBO Concocting a Phony Debt Crisis?: “The CBO assumes that Social Security and Medicare Part A will draw on the general fund of the US Treasury…

…to cover benefit shortfalls following the depletion of their trust funds, which at the current rate will occur in 2034. That would obviously lead to an exploding debt, but it’s a scenario prohibited by law. In the case of both programs, benefits must be paid either from revenue collected via payroll taxes or from accumulated savings in the programs’ trust funds. When those funds run out, full benefits will simply not be paid. ‘Because there is no borrowing authority, there is really a hard stop,’ said Goss.

Congress could pass a law saying that Social Security and Medicare Part A would begin drawing on the US Treasury general fund after 2034. Or, Congress could preemptively pass laws to avert the situation before the deadline; it could take the approach favored by progressives and increase revenue to the programs by lifting the payroll tax cap, or alternatively raise the retirement age and lower benefits. But the bottom line is the CBO projections disregard the actual law and assume a worst-case legislative scenario—and one that is politically unlikely, to boot…

Must-read: Jon Faust: “Still Crazy After All These Years”

Must-Read: : Still Crazy After All These Years: “For the past several years, the Congressional Budget Office has been offering frightening forecasts…

…about government debt growing out of control unless strong action is taken. While these forecasts have played a prominent role in policy debates, the CFE’s Jonathan Wright and Bob Barbera have for several years been arguing that those forecasts are, well, crazy. Or as the headline on Bob’s 2014 FT piece put it: ‘Forecasts of U.S. Fiscal Armageddon are Wrong.’ The key… is that the CBOs economic growth and interest rate projections jointly make no sense…. Under the CBO’s projected tepid growth projection, interest rates were highly unlikely to rise to the assumed levels….

We were glad to read in Greg Ip’s recent column that Doug Elmendorf, the CBO director responsible for those forecasts until recently, now agrees. Elmendorf and Louise Scheiner of the Hutchins Institute make the argument that:

the fact that U.S. government borrowing rates are at historical lows and likely to stay low for some time, implies spending cuts and tax increases should be delayed and smaller in size than widely believed.

It was Elmendorf’s CBO that helped stoke those widely-believed views now labelled as misguided. And as noted above, the CBO is still stoking. For the sake of coherent public policy, we hope that the CBO will listen to Elmendorf and Scheiner.

Must-read: Jared Bernstein and Ben Spielberg: “Preparing for the Next Recession: Lessons from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act”

Must-Read: : Preparing for the Next Recession: Lessons from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act: “Measures that can quickly respond to a recession by bolstering the economy…

…and at least moderating the downturn’s negative impacts are important. While the Federal Reserve lowers interest rates and expands access to credit, the President and Congress can tap various ‘stabilizers’ through budget and tax policy that can offset some of the financial losses that households experience and help them maintain higher levels of consumer spending…. The depth of the Great Recession and the slow recovery, however, serve as poignant reminders that monetary policy and automatic stabilizers don’t always do enough. Meanwhile, state balanced-budget requirements present a serious obstacle to recovery efforts…. But while ARRA was clearly effective, many of its interventions ended too soon, as the economic need for them persisted both at the macroeconomic level (growth and unemployment) and the household level….

Moving forward in anticipation of further recessions, a stronger set of automatic stabilizers would help…. Make UI’s EB program more responsive to economic conditions by having it take effect more quickly and remain in effect until hardship and labor market weakness are alleviated sufficiently, encourage ‘worksharing’ among employees by creating incentives for it through UI, strengthen basic UI benefits, and bolster UI’s financing system. Have temporarily higher SNAP benefits (and perhaps higher SNAP administrative funds for states) take effect automatically when a trigger, possibly tied to state unemployment rates, reaches certain thresholds. Make state fiscal relief, in the form of higher federal payments to help states cover their Medicaid costs, take effect automatically, possibly via the same mechanism that is used to trigger a temporary increase in SNAP benefits. PPrepare for additional discretionary steps during downturns by establishing a dedicated fund for subsidized jobs and job creation programs and considering one-time housing vouchers that can help struggling families keep their homes, pay their rents, and avoid homelessness…

Must-reads: March 24, 2016

- (1936): The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money

- : The State of American Politics

- : Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization

- (1936): A somewhat comprehensive socialization of investment…

- : Mission still not accomplished: To reach full employment we need to move fiscal policy from austerity to stimulus

- : Moving to the Innovation Frontier

- (2011): Zombie Marx

- : The Affordable Care Act at Six: Progress on Coverage, Costs, and Quality

- (1829): Contra Say’s Law: “Money, consequently, was in request, and all other commodities were in comparative disrepute…”

- (1819): The “General Glut”

- : Inputs in the Production of Early Childhood Human Capital: Evidence from Head Start

- : MMT and Mainstream Macro

- : Worthwhile Canadian Initiative: Reverse-Engineering the MMT Model

Must-read: John Maynard Keynes: “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money”

Must-Read: (1936): The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money: “Is the fulfilment of these ideas a visionary hope?…

…Have they insufficient roots in the motives which govern the evolution of political society? Are the interests which they will thwart stronger and more obvious than those which they will serve?

I do not attempt an answer in this place…. But if the ideas are correct… it would be a mistake, I predict, to dispute their potency over a period of time…. The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back. I am sure that the power of vested interests is vastly exaggerated compared with the gradual encroachment of ideas….

There are not many who are influenced by new theories after they are twenty-five or thirty years of age, so that the ideas which civil servants and politicians and even agitators apply to current events are not likely to be the newest. But, soon or late, it is ideas, not vested interests, which are dangerous for good or evil.

Must-read: Mark Thoma: “The State of American Politics”

Must-Read: : The State of American Politics: “Paul Ryan, in a speech…

…on the state of American politics, says:

We don’t lock ourselves in an echo chamber, where we take comfort in the dogmas and opinions we already hold.

Followed by:

… in 1981 the Kemp-Roth bill was signed into law, lowering tax rates, spurring growth, and putting millions of Americans back to work.

Bruce Bartlett:

… I was the staff economist for Rep. Jack Kemp (R-N.Y.) in 1977, and it was my job to draft what came to be the Kemp-Roth tax bill, which Reagan endorsed in 1980 and enacted the following year…. Republicans like to say that massive growth followed the Reagan tax cut. But average real GDP growth during Reagan’s eight years in the White House was only slightly above the rate of the previous eight years: 3.4 percent per year vs. 2.9 percent. The average unemployment rate was actually higher under Reagan than it was during the previous eight years: 7.5 percent vs. 6.6 percent…

What tools do central banks have left?

Central bankers are usually quite staid people. After all, when your pronouncements can easily swing stock markets and disrupt bond markets, you should be very careful about what you say. In normal times, central bankers should remain committed to being very reasonable and responsible. But it seems sometimes that the time for that old playbook has passed.

In the United States, the combination of our tepid recovery from the Great Recession, the low rates of inflation, and interest rates hovering around zero despite extraordinary amounts of expansionary monetary policy has provoked some rethinking of the old ways. Do we need new tools to guide economic growth moving forward? Or should we just amend the old ways?

Negative nominal interest rates, once thought to be an impossibility, are now being seriously considered as a tool for the Federal Reserve. Other central banks—including the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank—have already taken the dive and lowered their nominal interest rates below zero, but it’s uncertain if the U.S. central bank will jump as well when the time arrives.

Former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke doesn’t seem to consider negative rates a tool that would be wildly different from what’s been tried in the past. If interest rates have been cut to zero, he writes, “modestly negative rates seem a natural continuation; there is no clear discontinuity in the economic and financial effects of, say, a 0.1 percent interest rate and a -0.1 percent rate.” Whether the central bank can go negative (Bernanke says the legality of negative rates is uncertain) or will go there in the near future (he says it’s unlikely anytime soon) is very much up for debate. But there’s a real debate to be had.

Maybe new tools such as negative rates aren’t needed, though. The recent meeting of the Federal Open Markets Committee, the Fed’s policy-setting arm, has raised questions about the central bank’s use of “forward guidance” and its credibility when it comes to hitting its stated 2 percent inflation target. As Bernanke puts it in his post, central banks often refer to their guidance of policy by setting expectations through communications as “open mouth operations.” But the Fed seems to have tied its hands by setting expectations through its “dot plot” that there’s a set path for policy, despite its protests that the dots are not projections of the future path of interest rates. Perhaps the Fed would be better served by focusing on forward guidance that depends less on the calendar and more on economic thresholds.

But ultimately, these adoptions or reorientations of tools may just be picking at the edge of the problem. The Federal Reserve might now be facing the possibility of inflation slightly over its target of 2 percent after four years of missing the target on the downside. An overshoot would signal that the inflation target is really a target and not a ceiling, that inflation could go slightly higher in an effort to let economic growth really get a strong foothold. But if we’re to believe Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen’s remarks at the Fed’s latest press conference—in which she said the Federal Open Markets Committee was not trying to “engineer an overshoot of inflation”—then we shouldn’t hold our breath for overshooting.

Timidity, then, may be the problem that central bankers have to solve. As Ryan Avent of The Economist argues, it may be time for a monetary policy regime change. The Federal Reserve may test out new tools, but they may be for naught if new targets—such as a nominal gross domestic product target—don’t emerge. Central banks can experiment all they want with negative rates, helicopters, and different-colored dots, but a bit of resolve in the form of more dramatic, bigger-picture steps may be in order.