This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth has published this week and the second is work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

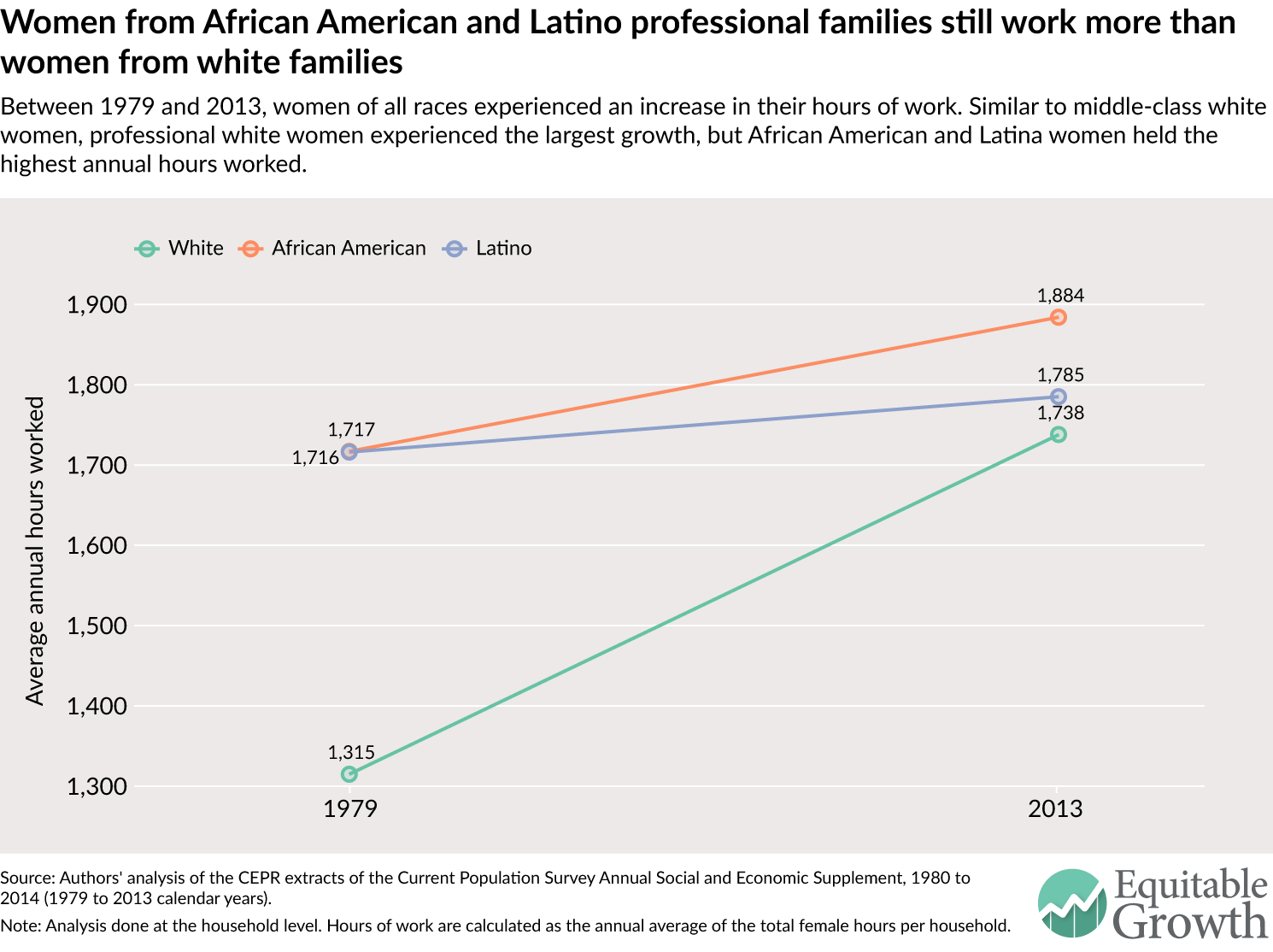

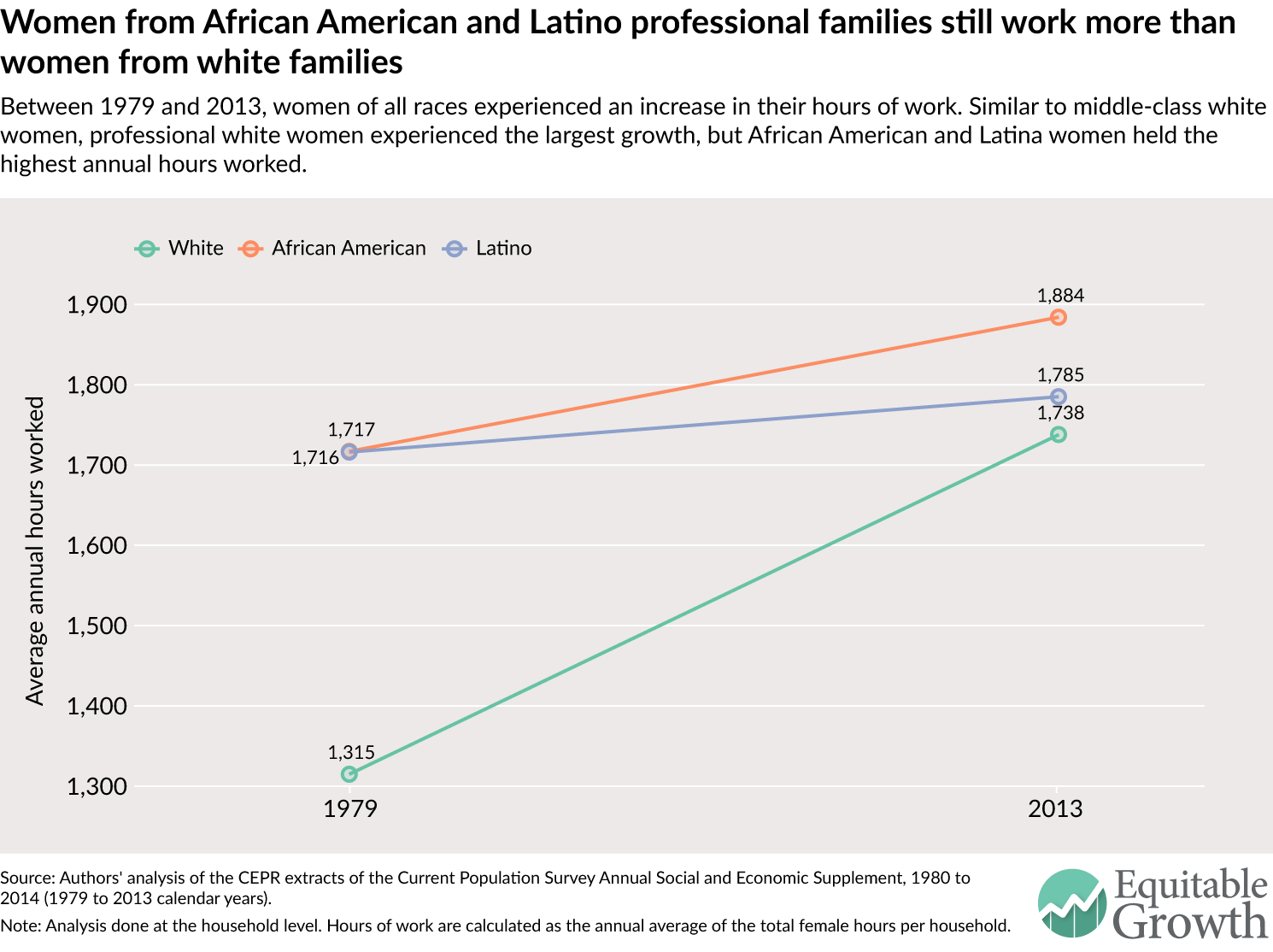

Two weeks ago, Heather Boushey and Kavya Vaghul showed how the increasing entrance of women into America’s paid labor force over the past few decades has propped up family income growth. In a new piece this week, Boushey and Vaghul show how these trends vary across race and ethnicity.

The rise of passive index investing and concerns about short-termism by corporations has sparked a debate about who gets to allocate capital in the United States. But in a way, this debate is also about who gets some of the increased profits of recent years.

A crisis is looming in the United States as many households haven’t saved enough for retirement. At the same time, we might have too much saving relative to investment opportunities. So how we should help improve retirement security?

The economies of high-income countries have become financialized over the past 30 years as credit has almost doubled as a share of gross domestic product. How does this affect the functioning of the macroeconomy? A new paper lays out some key stylized facts.

Links from around the web

The incarceration rate in the United States is incredibly high by both international and historical comparisons. As a result, sentencing laws are under increasing scrutiny. And the economic evidence, as Jason Furman and Douglas Holtz-Eakin argue, shows that the costs of incarceration now far outweigh the benefits. [nyt]

The welfare reform of the 1990s was intended to increase the labor force participation of women on the program. But the program also had extremely sharp benefit phase-outs, encouraging some women to work less in order to stay on the program. Patrick Kline and Melissa Tartari write up their paper on this topic. [microeconomic insights]

We’re all familiar with the dangers of subprime mortgages. But while those financial instruments have retreated from the scene, a new product has emerged that replicates many of their problems. Heather Perlberg looks into the rise of “seller-financed” home sales. [bloomberg]

Numerous writers and analysts (yours truly included) have raised concerns about increases in market concentration, declines in competition, and higher economic rents. Does this have a negative impact on economic growth? Dietz Vollrath says it depends, but it likely reduces innovation. [growth economics]

As the U.S. health care sector has more than a few problems, the Affordable Care Act aimed to change a wide number of things about the system—one of which is the medical debt. Margot Sanger-Katz details a new study on how the law is improving financial security. [the upshot]

Friday figure

Figure from “Across races, women bolster family economic security” by Heather Boushey and Kavya Vaghul

Figure from “Across races, women bolster family economic security” by Heather Boushey and Kavya Vaghul

Figure from “

Figure from “