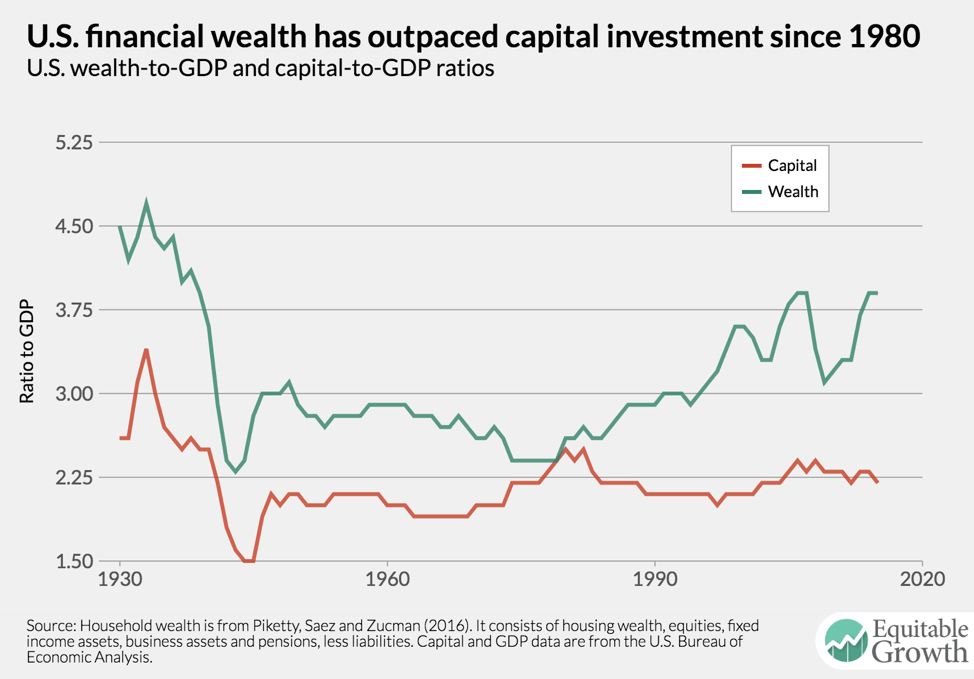

Long-term U.S. interest rates have been rising this year, with the yield on a 10-year Treasury bond increasing about half a percentage point since the beginning of the year. The rise in the yield over just the past few months may seem large, but looking at a longer time horizon since the early 1980s shows that the yield trend has been downward. (See Figure 1.) Is the recent uptick in 2018 the start of a new upward trend or just a blip in the current downward trajectory? That answer depends in part on what’s caused the long-term decline and whether that trend will continue. New research points at an important contributor to the decline in interest rates that may continue on for some time without policy changes: the high level of income inequality in the United States.

Figure 1

Recently released as part of the Equitable Growth Working Paper Series, a paper by Adrien Auclert of Stanford University and Matthew Rognlie of Northwestern University looks at how income inequality affects the amount of demand in the economy. Most people’s thinking about inequality’s impact on demand is through consumption, but that’s only one factor that economists need to consider. Higher levels of income inequality might reduce household consumption, but then other markets in the economy are going to adjust. Business investment (another piece of aggregate demand) is going to adjust after consumption declines, for example, and then, of course, there’s the reaction of policymakers in the form of monetary or fiscal policy.

Auclert and Rognlie work to show how income inequality affects or determines changes in demand through some of these so-called partial equilibrium effects and then how they are transmitted into general equilibrium-the equilibrium when all the markets in an economy clear. The two authors show that the processes are different depending upon the timeframe that the model is looking at.

In the short run, the key to understanding partial equilibrium is the relationship (or covariance) between income and the marginal propensity to consume. Understanding how much individuals will respond to a one-time shock to their income gives us the partial equilibrium response of consumption. Then this partial effect gets multiplied by the general equilibrium effects, which are determined by monetary policy, fiscal policy, and how much incomes will respond to the decline in employment during an economic downturn. What the authors find is that, in the short run, a rise in income inequality only slightly affects demand in the economy.

In the long run, however, the source of higher income inequality matters tremendously. If higher income inequality is due to higher income risks, or more volatile incomes, then that reduces demand in the economy quite a bit. That’s because the partial equilibrium effects related to consumption are driven by how much the demand for assets will increase depending upon changes to income risk. Essentially, if rich people are rich because they have more variable incomes, then they will have more of a demand for assets to use as precautionary savings. Increased demand for assets means reduced demand for current goods and services, which reduces overall aggregate demand.

The key here for the partial equilibrium effect in the long run is the sensitivity of asset demand to “idiosyncratic income risk.” If people are more likely to demand assets (save more money) for a given amount of risk, then higher income inequality will result in more saving and reduced demand. The general equilibrium multiplier here is similar to the one for the short run.

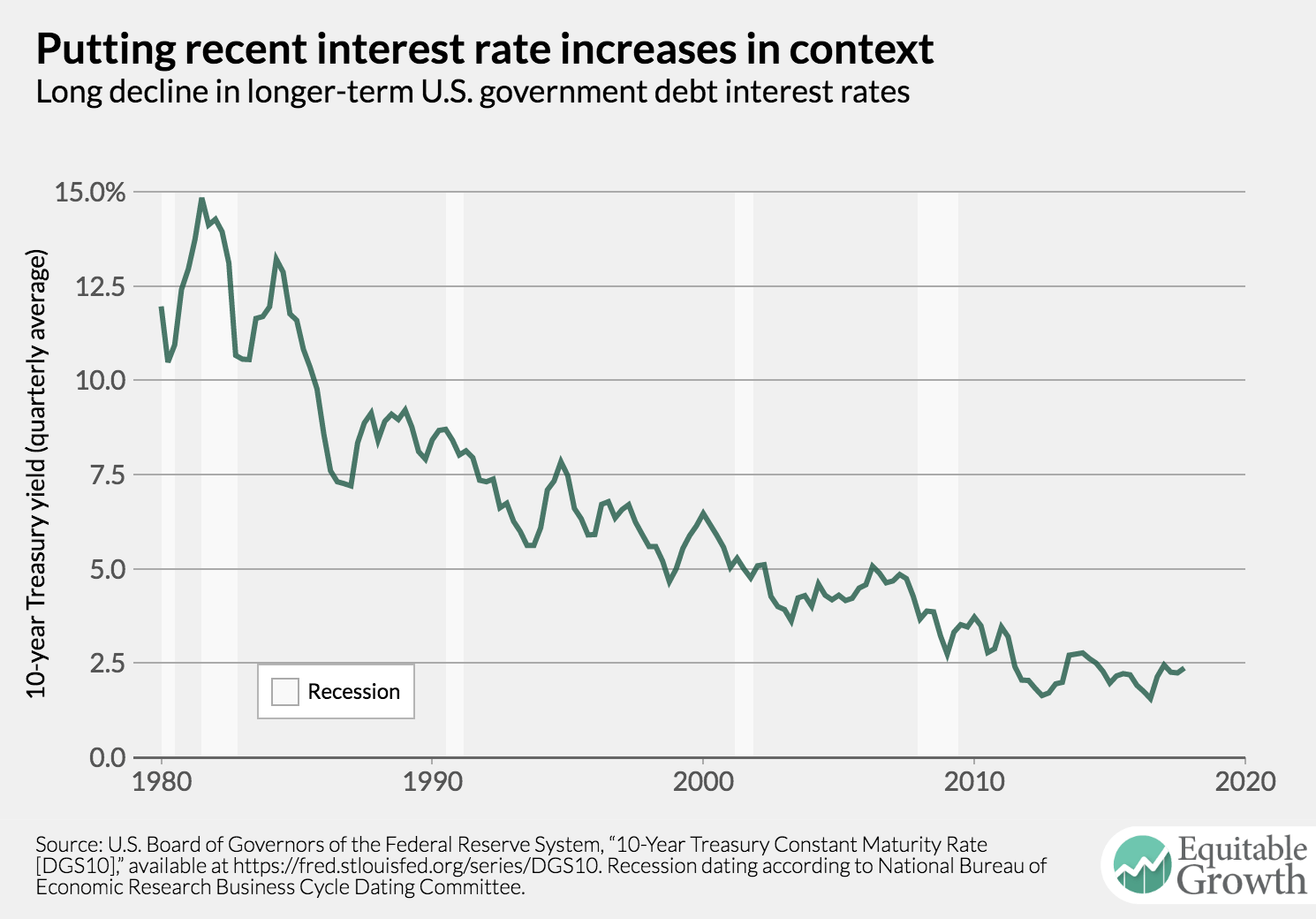

Using this long-run model, Auclert and Rognlie can give an estimate of how of the decline in the natural, or equilibrium, rate of interest can be explained by higher income inequality. If the increase in income inequality is because of higher income risk, then inequality is responsible for about 20 percent of the total 4 percentage point decline in interest rates since the 1980s. That leaves almost 80 percent of the decline to be explained by other factors, though other research finds important roles for factors that are unlikely to change quickly such as an aging population.

U.S. interest rates may be on the rise, but it’s not clear how long their ascent will last. The past 35 years have seen a significant increase in income inequality, an aging population, and a potentially large increase in some businesses’ monopoly power in the economy alongside other structural shifts that change the functioning of the economy. Until we see significant changes in those factors and others, interest rates don’t seem likely to rapidly ascend anytime soon.