This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is the work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Last Friday, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released new data on the state of wage growth during the second quarter of this year. According to the agency’s Employment Cost Index, accelerating wage growth is here. But does that mean it’s time for the Fed to hike interest rates?

With short-term and long-term U.S. interest rates at near historical lows, policymakers are coming around to the idea that short-term deficits can increase a bit. But when they’re thinking about what any new borrowings should be spend on, they should keep in mind different rates of return.

The share of students eligible for subsidized school lunches in the United States is a measure of economic disadvantage that is widely used by policymakers and researchers. But a new paper shows how looking at just current student eligibly doesn’t fully capture the levels of disadvantage some of these students face.

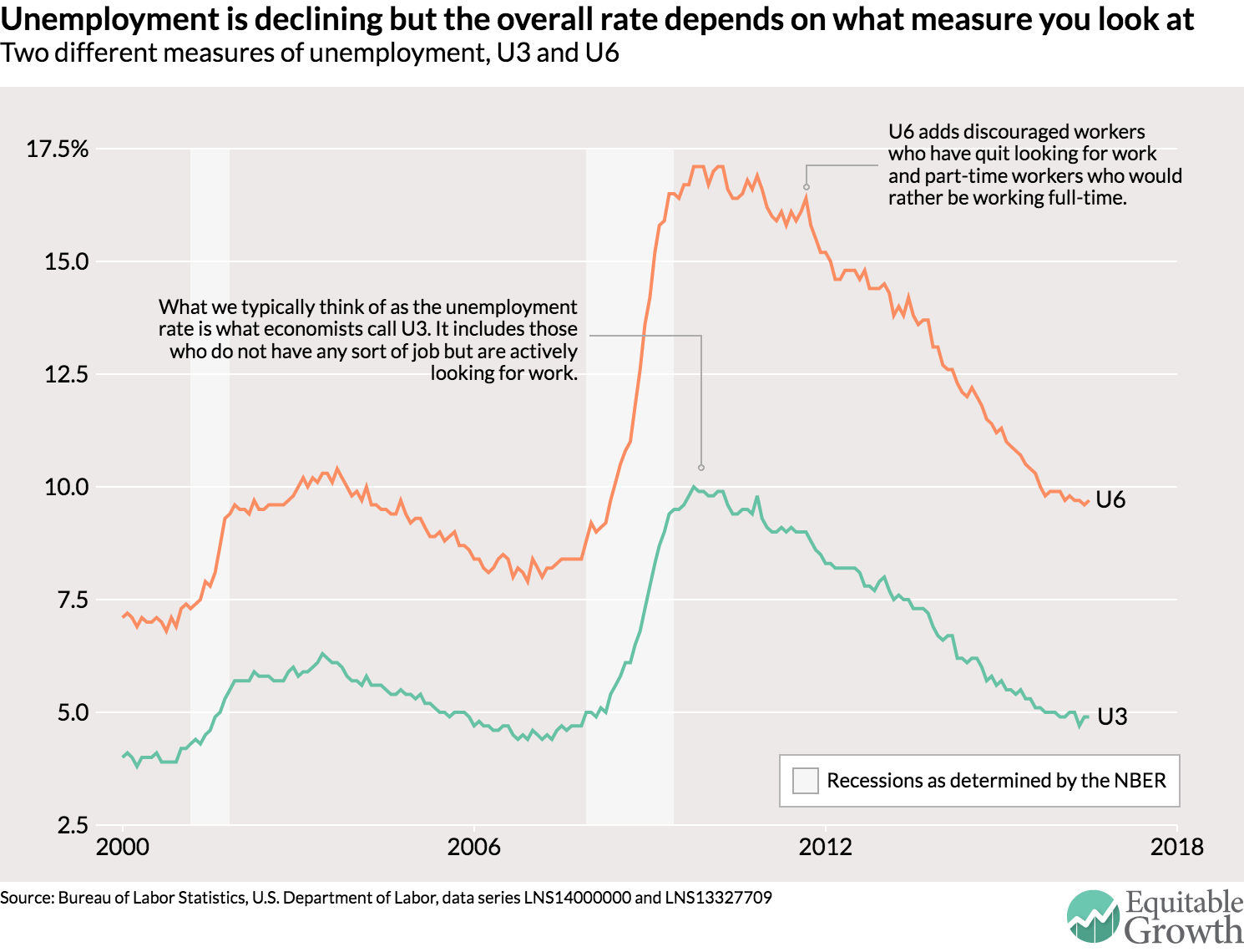

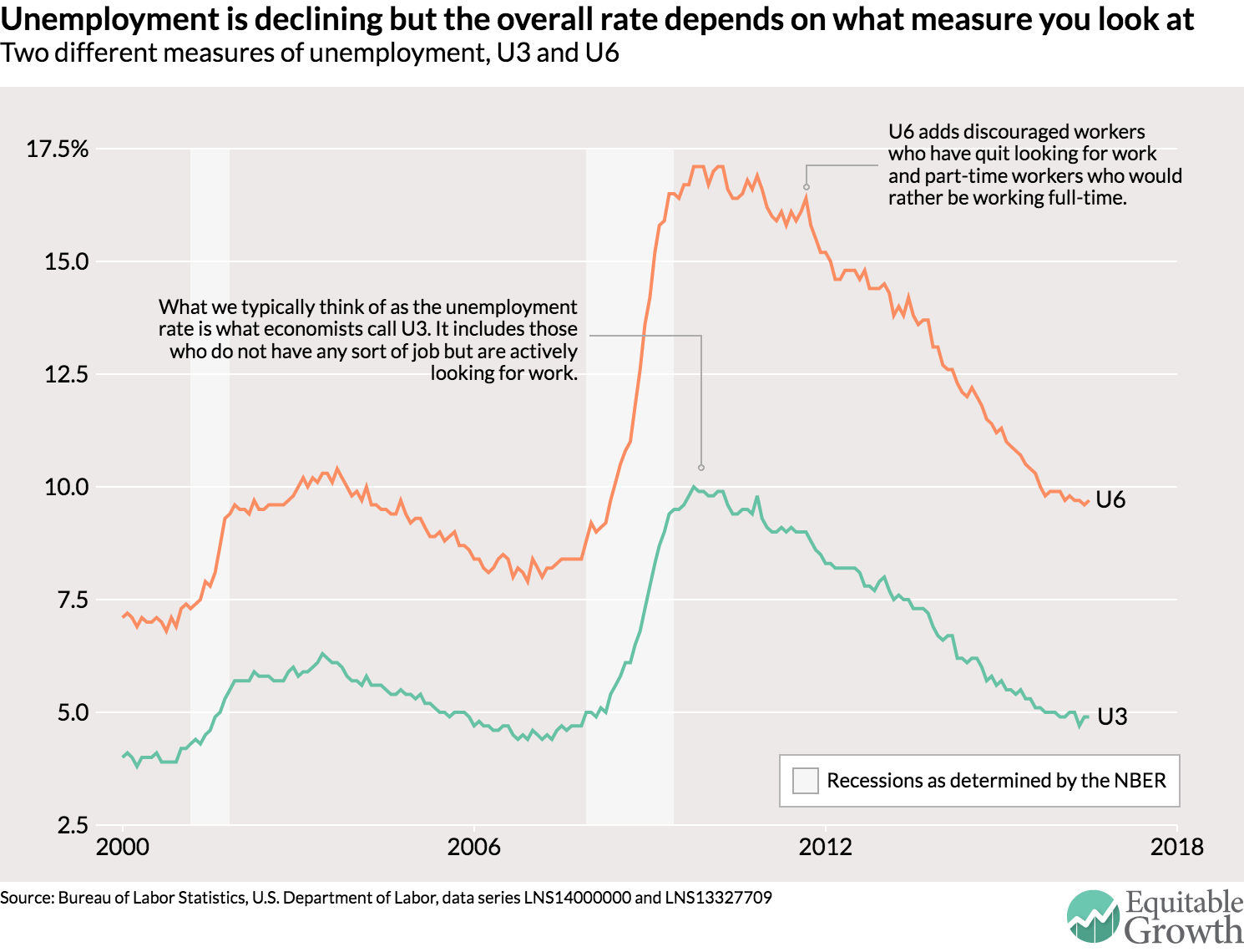

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released new data on the labor market in July earlier today. Check out five important graphs from the data picked by Equitable Growth staff.

Links from around the web

U.S. economic growth hasn’t been as strong as some people might over the past decade and a half. How can policy help boost growth? Narayana Kocherlakota argues for three big policy pushes: infrastructure investment, a temporary elimination of the employer side of the payroll tax, and a time-dated universal basic income. [bloomberg view]

One reason why economic growth has been relatively slow is that the U.S. population is aging as older workers leave the labor force. But a new paper, written up by Claudia Sahm, looks at how an aging population may be reducing productivity growth. [macromom]

The European Union is now the largest contributor to the “global savings glut” and has quite a few economies that could use a boost in growth. According to the International Monetary Fund’s assessment, the EU should recommend fiscal stimulus. Brad Setser sees if this is actually happening. [follow the money]

What’s at the heart of the gender wage gap in the United States? Sarah Kliff digs into this question and the related research and comes back with a story—told in part with stick figures. [vox]

The U.S. government has a number of statistical agencies that all create important data. But they often can’t share useful data among themselves to help improve these data sets. Michael R. Strain writes that data synchronization could help alleviate this problem. [aei]

Friday figure

Figure from “Equitable Growth’s Jobs Day Graphs: July 2016 Report Edition” by Equitable Growth staff