This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is the work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

The U.S. economy might need an injection of more inflation. But many economists point to models that show higher inflation would have significant costs. A new paper comes to a different conclusion, examining how those costs might not change much with the rate of inflation.

Cutting the U.S. corporate income tax to help boost wages sounds like a counterintuitive idea. But if we think the incidence of the tax falls mostly on labor, it makes sense. Yet it seems unlikely that labor bears most, if any, of the tax burden, which mainly falls on capital.

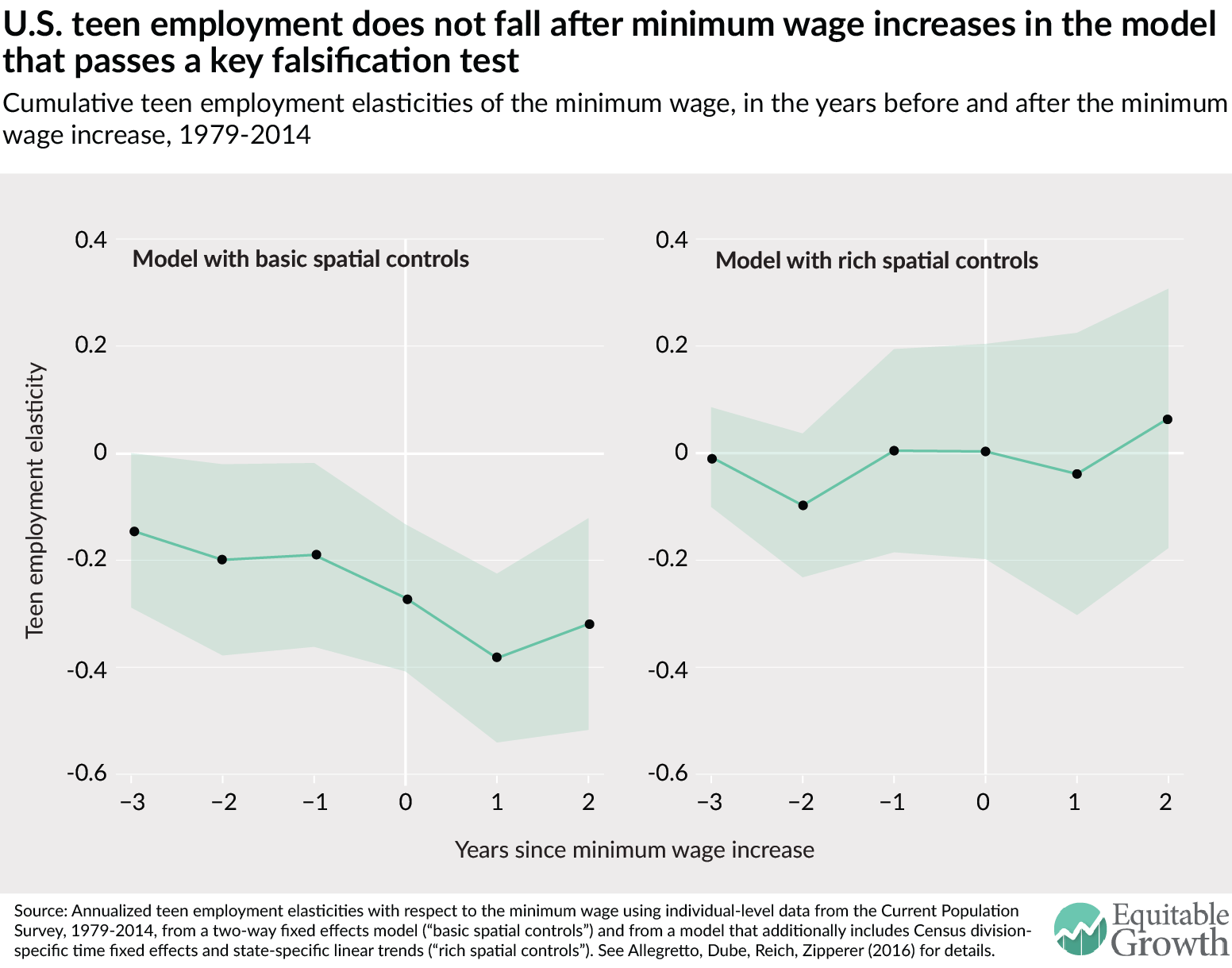

Does raising the minimum wage in the United States reduce teen employment? A new paper in this debate argues that studies finding a negative impact do not account for pre-existing labor market trends in states before minimum wage hikes. Ben Zipperer, a co-author of the paper, provides a nontechnical explanation of the paper.

The last few years have seen significant increases in subprime auto lending across the country. For anyone who remembers the last big uptick in subprime lending, this might cause some concern about sparking a new recession. Those concerns are overblown.

Despite trends toward increasing gender equity in the workplace, occupational segregation by gender is still pervasive in the U.S. labor market. Will McGrew shows how this segregation is a problem for the wages and economic growth.

Links from around the web

Earlier this week, John Williams, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, released a new paper on rethinking monetary policy in an era of low interest rates. Larry Summers reacts to the paper and suggests some more policy reforms. [wonkblog]

Part of the Federal Reserve’s mandate is to promote “maximum employment” with its conduct of monetary policy. But there are clear differences in how changes in unemployment affect different racial groups in the United States, particularly African Americans. Narayana Kocherlakota points out that positive trend of Fed policymakers starting to acknowledge this fact. [bloomberg view]

Is there any connection between the decline in the labor share of income and measured productivity growth? Dietz Vollrath explains (with a baking analogy) how a change in the distribution of income can impact productivity growth. [growth econ]

The causes of rising “inter-firm inequality” is a big open question in economics. Looking into this question, Claudia Sahm digs into a big paper on the role of firms in the rise of income inequality. [macromom]

Due to the recent exit of certain insurers from the new U.S. insurance exchange markets, concerns about competition are becoming more prominent. With those concerns in mind, Yale University’s Jacob Hacker brings back his proposal for a public option—an insurance plan rule by the federal government – for the exchanges. [vox]

Friday figure

Figure from “Credible research designs for minimum wage studies” by Ben Zipperer.