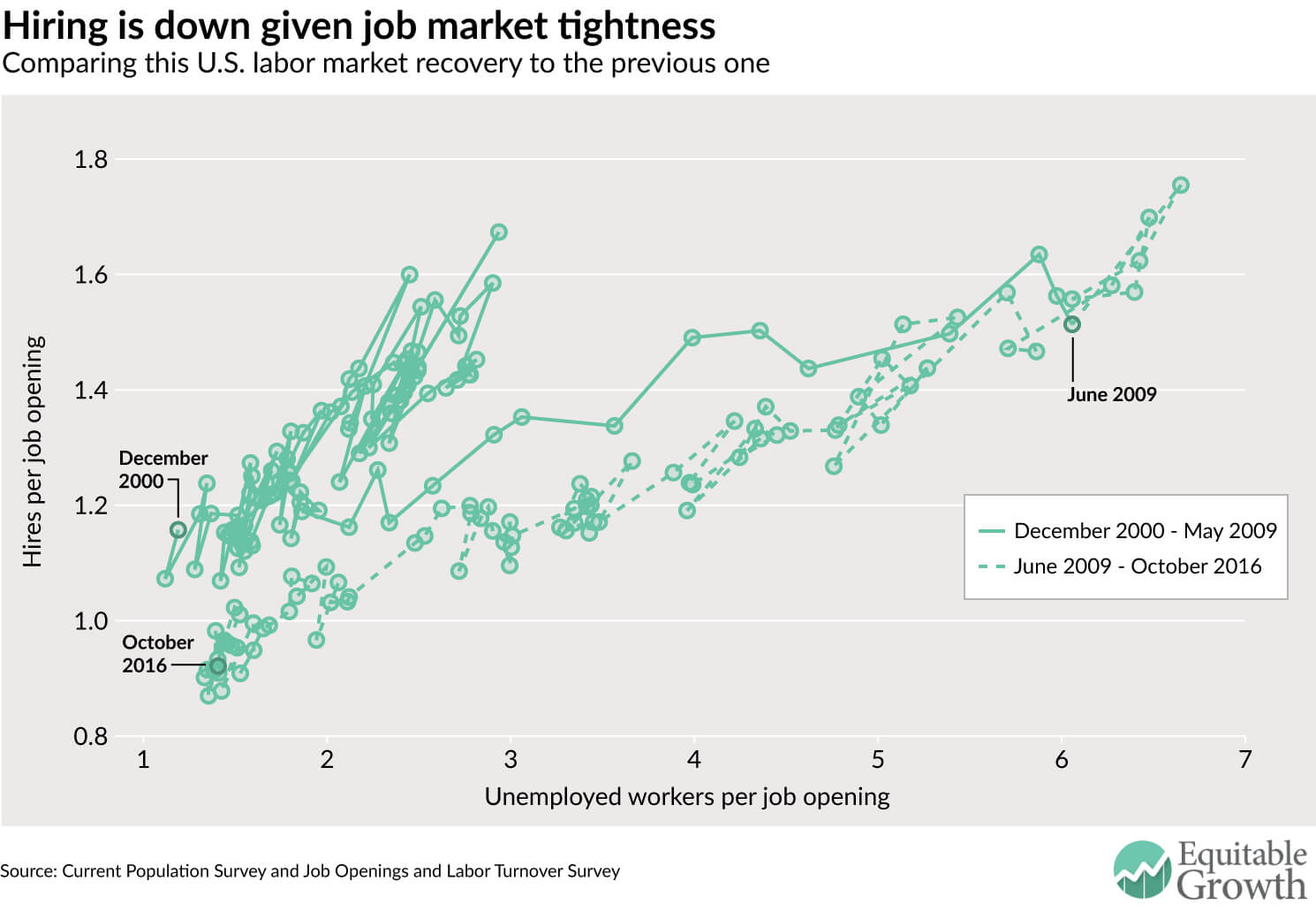

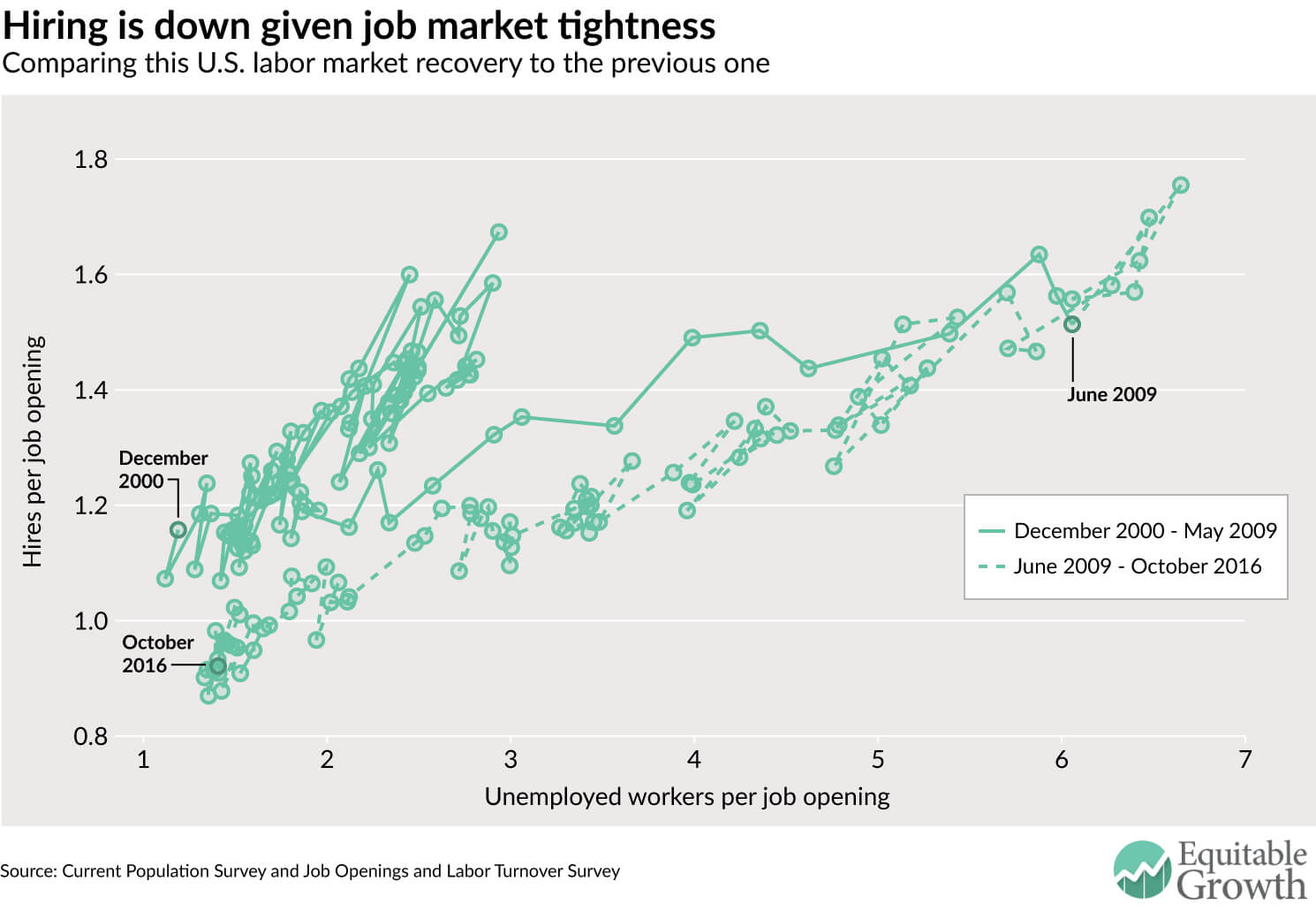

The U.S. labor market is heading toward full employment in 2017. But not every metric of labor market health seems to be in line with previous periods of labor market tightness. There’s less hiring for each job opening, relative to years past. That is, the data indicate that the number of people hired is out of line with our experience during past economic recoveries. Employers are getting fewer hires out of job openings than at similar levels of labor market tightness in the past. (See Figure 1.) New evidence points to a lack of movement between jobs, a problem that has implications for the strength of U.S. wage growth.

A change in the relationship between labor market tightness and the vacancy yield could indicate that something about the process of matching workers to jobs has shifted. It looks like for each job opening, there’s less hiring. This shift may be related to the fact that employers are posting more job openings than in the past, but policymakers need to take into account hiring patterns among different types of job seekers as well.

In a working paper released late last year, economists Peter Diamond of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Ayşegül Şahin of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York take a look at this so-called “matching function”—the relationship between hiring and labor market tightness. Specifically, they disaggregate the function for a number of characteristics of workers and employers.

One particularly interesting disaggregation looks at differences in hiring for workers with different labor-force characteristics. Diamond and Şahin compare hiring for workers who were previously out of the labor force, those who were officially unemployed, and those who were previously employed. They find that hires of those who were unemployed and out of the labor force are more sensitive to the overall health of the labor market, which means these new hires rise and fall more (and unemployment rises and falls more) compared to hires of those who were previous unemployed.

Yet looking at hires similar to the way they are presented in Figure 1 but with data going back to 1975, the economists show hires of those who were previously employed during the current recovery are far below the trend from previous recoveries. Hires of those out of the labor force are in line with previous recoveries, and hires of those who were unemployed are slightly lower, but the recent experience for hires of those who are currently employed is way out of line. Hires of these already employed workers has been quite weak compared to the tightness of the labor market.

Such “job switching” has been trending downward for all age groups since 2000. This lack of movement among those with jobs might be a sign that sticking at a job is paying more than in the past, but there’s no evidence that the boost to earnings from longer job tenure has increased in recent years. Something is amiss with either the willingness of workers to switch jobs or employers’ interest in hiring already employed workers. As we look at the labor market moving forward in 2017, this is a trend to keep an eye on.