Recent research documenting an increase in wealth inequality since the 1980s has led to calls for the increased taxation of wealth, including a high-profile proposal from Thomas Piketty, the Paris School of Economics professor and author of Capital in the 21st Century. But there is relatively little empirical research on wealth taxes relative to other types of taxes on business and investment income. A new working paper by Katrine Jakobsen of the University of Copenhagen, Kristian Jakobsen of the Social Capital Fund, Henrik Kleven of Princeton University, and Gabriel Zucman of the University of California, Berkeley breaks new ground on this topic by examining the experience of Denmark, which imposed a tax on wealth until the end of 1996.

The researchers rely on Danish administrative records on wealth that have been collected since 1980. These records were used to administer the Danish wealth tax until its abolition and continued to be collected even after the tax was repealed. The Danish wealth tax was an annual flat-rate tax on net worth above an exemption threshold. Net worth is the value of a families’ assets less the value of their debts, and the tax base included a wide variety of assets such as cash, deposits, bonds, equities, business assets, and housing, though the tax did not apply to pension wealth. The exemption threshold varied over time, but throughout the period the researchers study, the exemption was set high enough to exclude 97 percent of the population.

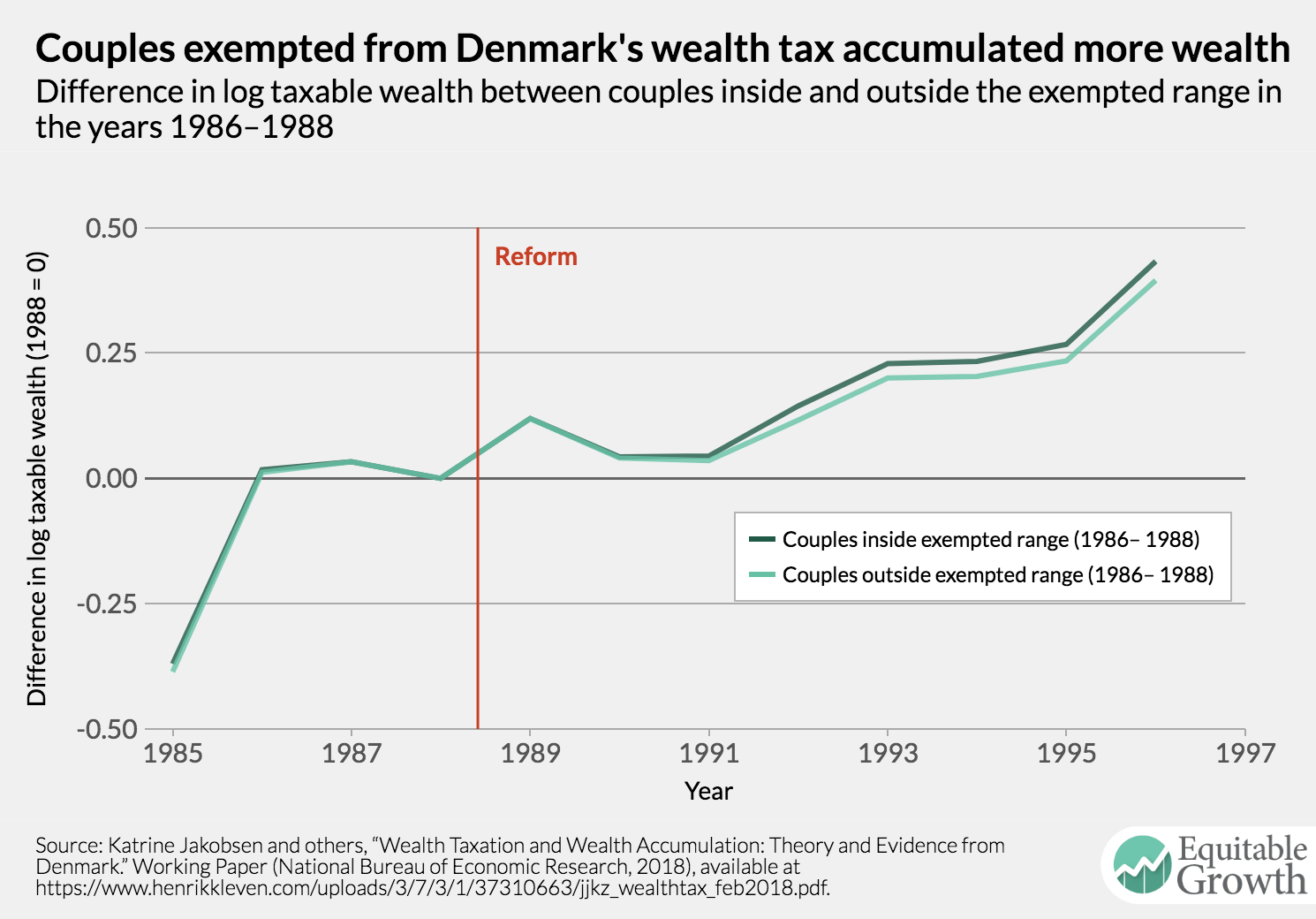

Denmark reduced the rate of its wealth tax from 2.2 percent to 1 percent between 1989 and 1991, and then repealed the tax entirely at the end of 1996. The 1989 tax cuts also increased the exemption threshold. The researchers study two quasi-experiments resulting from these changes. The first compares taxpayers for whom the increase in the exemption eliminated wealth taxes relative to other similar taxpayers still affected by the wealth tax. The authors estimate that the elimination of the wealth tax for this group of taxpayers—in approximately the 98th to 99th percentiles of the wealth distribution—led to a roughly 10 percent increase in wealth holdings after 8 years.

The second experiment relies on a group of very wealthy taxpayers—in the top 1 percent of the wealth distribution—who faced a zero marginal wealth tax rate prior to the tax cuts because of a separate provision of the law limiting the overall average tax rate. The researchers find that the reduction in the rate of the wealth tax led to a roughly 30 percent increase in accumulated wealth after 8 years among other similar taxpayers relative to this group of taxpayers who did not face a positive marginal tax rate on wealth. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The four researchers then construct a model to simulate the lifecycle profile of wealth to estimate the effects of changes in wealth taxation on the long-run level of wealth based on the quasi-experimental evidence. For families between the 98th and 99th percentiles of the wealth distribution, the authors find that the tax cut they study results in increases in wealth over a period of about 20 years. Wealth levels are about 20 percent higher than they would have been without the tax cut. Interestingly, families in this range of the wealth distribution save less at the lower tax rate for most of their lives, and the higher wealth levels at death reflect the mechanical effects of the reduced tax rate. For families in the top 1 percent of the wealth distribution, the tax cut the authors study led to levels of wealth that were about 70 percent higher than they otherwise would have been after 30 years.

These findings suggest that wealth taxes can have a quantitatively important effect on wealth inequality and thus may be a useful tool for policymakers interested in reducing wealth inequality. (Interestingly, the authors note that wealth inequality did not increase sharply in Denmark during the period they study and suggest an increase in pension wealth as a countervailing force.) Yet in this relatively understudied area, more research is needed to better understand how people respond to wealth taxes and how such taxes influence patterns of wealth accumulation.