Broken plumbing: How systems for delivering economic relief in response to the coronavirus recession failed the U.S. economy

Overview

Sudden economic contractions are dangerous. Individuals experience income shocks that leave them hungry, sick, and frightened. And if left unchecked, these shocks spread. When people lose income, they stop spending, businesses lose customers, layoffs begin, more people lose income, and more people stop spending. This cycle sends hardships rippling through the population.

Well-crafted economic delivery systems to absorb these shocks are crucial to stopping this cycle, but some policymakers in the United States construct them poorly on purpose. They design systems well that transfer cash to the powerful but use faulty delivery systems as a backdoor way to tamp down aid and assistance to everyday people.

To understand how economic delivery systems can stop the cycle of economic contraction, it’s instructive to look back over the past two decades. Economists drew a clear lesson from the Great Recession a decade ago—delivering money to the hardest-hit individuals and families is one of the best tools to break the cycle of economic contraction. When people have money to buy essential goods and services, businesses maintain their customer base and don’t need to lay off staff. And, as Harvard University economist and Equitable Growth Steering Committee member Karen Dynan and her co-authors’ research found, delivering money to working- and middle-class Americans is the best way to create a virtuous cycle to stabilize the U.S. economy amid an economic downturn.

In the early days of the coronavirus recession, Congress realized this and acted, appropriating more than $2.3 trillion to halt the sharp economic downturn. But earmarking money for individuals and families is not enough. Money needs to actually reach consumers for them to spend it and stabilize the economy.

What are the steps between policymakers acting and families having money to spend to meet their needs? A metaphor can be instructive here. Think of the appropriated resources as water, stored in an aquifer. When resources are delivered effectively, a consumer will turn on the tap at her bathroom sink, and the water will flow. To get from the aquifer to the tap, the water flows through a plumbing system. When there are problems with the plumbing, consumers find their taps empty.

Well-functioning delivery systems, like plumbing systems, are essential to stopping the cycle of economic contraction. At the onset of the coronavirus recession, Congress decided to deliver money to consumers using a variety of programs. Each program has its own set of plumbing systems, beset with its own challenges. As economist Esther Duflo at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology notes, economists have a responsibility to not just create theoretical models but also engage in the messy, complicated work of ensuring that our economic “plumbing” is effective.

It is tempting to look at our broken plumbing and feel resigned that it has to be this way. Fixing delivery systems is a relatively boring and decidedly challenging task. But that perspective misses an important fact: For some people and businesses, delivery systems do work well. In fact, they tend to be incredibly effective for the most powerful members of our society. It’s not that good plumbing is too hard to build or that it naturally breaks down over time. Rather, our policymakers intentionally underresource the systems that deliver aid to everyday people, while quietly maintaining systems that efficiently funnel resources to the powerful.

Using faulty plumbing is a discreet way to cut off aid from those with great need but little political power. It can also be a way to deliver aid through channels that provide profit-making opportunities to private plumbing systems that pop up to fill gaps left open by absent or rusty public plumbing. In good times, the burdens of this system are borne primarily by the very vulnerable. In bad times, economic shocks spread more widely, and the plumbing problems affect more people.

Below, we detail four delivery systems tasked with providing relief during the coronavirus recession— relief targeted to small and large businesses, Unemployment Insurance, direct payments to consumers, and paid leave programs—each of them emblematic of a different plumbing problem. Looking at business rescue programs, we see pipes well-designed to flow easily to people with power, while the taps of the less powerful remain dry. Looking at Unemployment Insurance, we see the failure to invest in pipes, preventing these benefits from flowing smoothly to people who need them the most. Looking at direct payments, we see who profits when the plumbing is routed through costly private systems that twist and turn, enabling the powerful to siphon off of the plumbing. And looking at paid leave, we see what happens when policymakers build no pipes at all and suddenly need to turn on a spigot when the economy hits a drought.

To summarize this research brief’s conclusions, policymakers must invest in our economic infrastructure if our economy is to emerge from the COVID crisis more resilient. This includes:

- Re-engineering plumbing to deliver aid to those who need it most in a manner just as quick as our most sophisticated plumbing for the well-connected and well-resourced. This problem comes into stark relief with regard to business rescue programs.

- Fixing broken plumbing that has been degraded by years of deliberate neglect. An example of this rusty plumbing is embodied with the degradation of our Unemployment Insurance systems.

- Re-routing plumbing to deliver aid directly to the most vulnerable and eliminate costly detours that happen along the way. This brief discusses how a public payment system has been supplanted by private delivery channels that are both slower and costlier to our most vulnerable individuals and families.

- Building new plumbing for new programs that invest in an equitable economy. The absence of a paid leave delivery infrastructure has hobbled our ability to quickly and efficiently set that up in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic.

Business rescue programs—unequal plumbing

Challenges in small business rescue systems

Previous writing from the Washington Center for Equitable Growth discusses how mechanisms to aid small businesses are ad hoc, unfamiliar, and difficult to scale up to reach all impacted firms, while mechanisms to aid medium- to large-sized businesses are efficient, well-practiced, and can be deployed at scale. In other words, the economic plumbing to help our small businesses is rusty and degraded, while the plumbing that serves medium- to large-sized businesses is sturdy and resilient.

How is this playing out during the coronavirus recession? News articles declare that “the small business die-off is here,” notwithstanding the $670 billion approved by Congress to save small businesses via the Paycheck Protection Program. Reporting shows that small business owners did not feel confident that they could meet PPP requirements in time for loans to convert to grants, and that even for those who did receive small business loans, the support may not be enough to cover expenses during periods of mandatory lockdown or partial business closures. A survey of research on the Paycheck Protection Program shows that the loans were not properly targeted to the geographic areas hit hardest by the pandemic or its economic effects, and were not designed in a way to prevent avoidable layoffs. Because the assistance provided by the PPP was relatively shallow in comparison to the shock faced by most small businesses, the program ended up serving as a liquidity backstop for small businesses that needed a temporary boost, rather than a lifeline for the most devastated businesses.

The funding also likely arrived too late for many businesses. Recent research from Opportunity Insights, led by former Equitable Growth Steering Committee member Raj Chetty, finds that small businesses providing services that require face-to-face contact in certain ZIP codes saw an 80 percent drop-off in revenue largely before government rescue money was even available. Moreover, early survey research is showing that small businesses owned by Black and Latinx entrepreneurs are suffering particularly acutely.

The story is different for medium- to large-sized businesses, whose aid came largely via lender-of-last resort interventions by the Federal Reserve rather than through appropriations by Congress. The Federal Reserve’s stated commitments to support the economy across a number of interventions had the effect of bolstering these businesses’ ability to raise capital, even before most policy actions were undertaken. So, it doesn’t even much matter when the Fed starts to lend to companies or buy their bonds because the mere reassurance that the Fed will step in is enough to soothe the markets that serve medium- to large-sized businesses. Investment-grade, or the most creditworthy, U.S. companies issued record-breaking amounts of debt during the first few months of the coronavirus recession and have continued to do so. Junk bonds, or those that are backed by less creditworthy but still medium- to large-sized companies, are strongly rebounding too.

The gap between the efficient business rescue programs for medium- to large-sized businesses and laggard small business rescue programs was known to policymakers well before the coronavirus pandemic caused the latest recession. After the global financial crisis of a decade ago, the stock market and bank profits rebounded quickly, while small businesses recovered much more slowly. While the Federal Reserve at that time was able to calm markets with monetary policy interventions and bail out large financial firms over the course of mere days, small business rescue programs never received a needed revamp.

Fast forward to today. Markets rightly believe Fed Chair Jerome Powell when he says that the Federal Reserve is “not going to run out of ammunition,” largely because the Fed took extraordinary actions a decade ago when faced with the previous crisis.

Small businesses do not hear the same reassurances and would have no reason to believe such statements even if they were declared. In fact, multiple government oversight reports and pieces of journalism document how small business aid was slow to arrive for eligible firms after natural disasters over the course of the past decade. This pattern was replicated on a larger scale during the current crisis, when the U.S. Small Business Administration was tasked with deploying funding provided via the Paycheck Protection Program to ailing small firms.

There certainly are success stories for small businesses due to the Paycheck Protection Program, yet the small business aid also was beset by administrative chaos at its inception. The Small Business Administration website crashed on its first day of launching and many times thereafter, and many small businesses remain in grave danger. One survey of small business owners shows that more than half of them expect to be out of business in the 6 months after the survey was taken in April 2020.

Profit-seeking in private rescue systems

In the case of both programs—both the insufficient small business rescue efforts and the efficient medium- to large-sized business rescue efforts—it should be noted that the government lacked the infrastructure to administer programs directly. In fact, each was administered by agents in the financial sector, rather than through the direct public provision of assistance.

This means that certain private firms, usually the most advantaged and well-connected, profit from the taxpayer-directed deployment of rescue aid. That profit represents funds that reinforce existing political power and that could otherwise be channeled back into helping those suffering.

In the case of small business rescue programs, the Small Business Administration, lacking staff or technical capacity to loan hundreds of billions of dollars using in-house capacity, relied on financial institutions to intermediate the delivery of financial aid from taxpayers to eligible small firms. In exchange for these services, lenders received more than $18 billion in fee income from processing Paycheck Protection Program loans—money that was deducted from the pool of funding available for small businesses.

By intermediating aid through the banking sector, the program also reinforced existing inequities in small business credit, at least according to anecdotal reports. The New York Times reported that a large small business lender established a “concierge service” for VIP business clients, allowing them to bypass call center wait times and avoid online portal snafus. As stated earlier, other stories documented the troubles faced by Black- and Latinx-owned small businesses in accessing funds, repeating longstanding discrimination in small business funding from the banking sector.

Again, this policy choice is not inevitable. Congress could have found ways to directly compensate businesses using systems similar to best practices from abroad. Denmark’s business rescue program, for example, had businesses apply directly to the Danish Business Authority for rescue aid. Denmark is now on track for a much less dramatic collapse in GDP this year, compared to peer countries, due both to the success of public health measures and economic rescue programs in the country. An efficient and already well-developed U.S. Small Business Administration, with pre-existing relationships with the IRS or payroll processing companies, could have worked to release aid in a more efficient and equitable manner.

One natural experiment in the United States is the state of North Dakota, which led the nation in small business rescue funding received per small business worker in the state. Observers credit the Bank of North Dakota, a public bank, for the state leading in the deployment of small business funds. In the words of Robert Hockett, a Cornell University law professor and alumnus of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, in a comment to The Washington Post, “there was no leakage—the sort of ridiculous fee-charging that tends to happen when you do it through larger banking entities.”

He added that the North Dakota model “isn’t really designed to maximize revenue lines by finding as many places to assess fees or brokerage charges as possible.” Though the bank offers few retail services or direct loans, it did serve as a clearinghouse to community banks, educating them about the new program, coordinating across the state, and buying slices of loans from local lenders where needed. The amount and type of help available in North Dakota was clearly well-practiced and scaled to the extent of the crisis in the state.

In the case of large business rescue programs, profit-seeking firms also sit at the center of aid programs. The Federal Reserve is being supported by asset management firms BlackRock, Inc. in the purchase of corporate bonds and Pimco Company in the purchase of commercial paper. Both are programs designed to boost large businesses’ financial health. All told, BlackRock and Pimco are under contract to purchase hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of financial investments on behalf of the Fed, with BlackRock, for example, slated to earn around $40 million in profit from the services it’s providing.

This raises significant conflict of interest concerns, as each company is also a large shareholder or bondholder in many of the companies whose financial investments they may buy on behalf of taxpayers. In the case of BlackRock, the company was also tasked with purchasing exchange-traded funds, and early reports show that BlackRock ETFs were the primary beneficiaries of BlackRock purchases as an agent of the Federal Reserve. Other observers point to relatively lax conflict of interest standards in place within Federal Reserve financial agent contracts, allowing potentially unfair access to market-moving information. And while these contracts will come up for a bid by the summer, they were initially granted by the Fed on a no-bid, temporary basis in response to the coronavirus recession emergency.

The use of these firms to administer rescue programs on behalf of the Federal Reserve is not a new phenomenon. The same approach was used in response to the 2008 financial crisis, underscoring that the Fed and policymakers have had time to consider alternative approaches to responding to a financial emergency and chose not to build public plumbing, but instead to rely merely on private plumbing. This represents a missed opportunity, as the Federal Reserve System employs almost 23,000 individuals, including sophisticated lawyers, economists, and market experts, and its budget authority is unlimited and set outside the congressional appropriations process. Given that this is the second major rescue program in more than 12 years, it stands to reason that it may be in the public’s best interest to develop this expertise in-house.

Alternatively, scholars such as Saule Omarova and Robert Hockett, both from the Cornell School of Law, suggest that Congress create a National Investment Authority that could serve as an institutional bailout manager, with democratic governance, to manage taxpayer investments in private enterprises with a fiduciary duty to the public. Similar proposals have been floated in major news outlets, harkening back to the Great Depression’s Reconstruction Finance Corporation, and in a piece by Todd Tucker, the director of governance studies at the Roosevelt Institute.

The plumbing that serves our least well-resourced constituencies—small businesses—is rusty, compared to the plumbing that serves medium- to large-sized businesses. Compounding that imbalance is the fact that the very firms that benefit from the efficient plumbing also manage to profit from the laggard plumbing available to others, reinforcing inequities in a feedback loop that accelerates during times of crisis.

Unemployment Insurance—rusty plumbing

At a moment when nearly 1 in 4 U.S. workers is not receiving a paycheck due to a pandemic that is clearly beyond their control and taking place in a country with no paid leave social insurance program, Unemployment Insurance is an obvious choice for delivering income to those who lose work due to the pandemic and its economic fall-out. Indeed, Congress recognized this when they gave states the ability to modify rules affecting the receipt of Unemployment Insurance to suit the conditions of the pandemic, and again when they established three pandemic-specific Unemployment Insurance add-ons: one increasing the benefit amount, another lengthening the benefit duration, and a third expanding the group of people eligible for benefits to include independent contractors, those with low earnings, and independent contractors.

Yet when people went to access the benefits they were entitled to under the law, many were greeted by crashed websites, jammed phone lines, and even instructions to line up in person to receive paper applications. The $600 weekly increase took weeks to implement, and in some states, the program expanding benefits to new groups of claimants took months. While some policymakers try to pass off this state of affairs as an unexpected tragedy—a sad coincidence that the system was out of shape just when benefits were needed most—the difficulties with benefit delivery are the result of decades of conscious choice by policymakers to starve the system of the resources it needed most. With computing systems that are hard to navigate for claimants and challenging to update for administrators, and without adequate resources for staffing and system updates, the plumbing for delivering Unemployment Insurance benefits is broken from years of neglect.

Unemployment Insurance program administration is funded through federal taxes based on employee payroll—referred to as FUTA taxes after the Federal Unemployment Tax Act. Taxes are collected at a rate of 0.6 percent (the FUTA tax rate is 6 percent, but a 5.4 percent credit is applied for state taxes paid) and are levied on the first $7,000 of earnings for each worker on an employer’s payroll. For a full-time, year-round employee, the FUTA tax is $42 per worker per year.

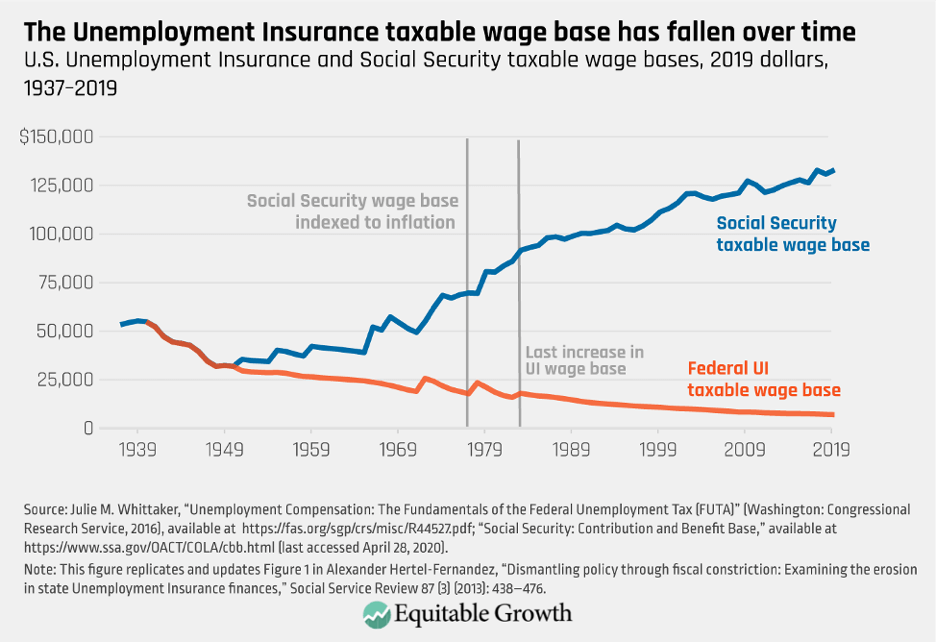

These taxes are technically charged to employers, but research finds that employers pass the cost on to workers by paying them less. This revenue is tasked with not only maintaining more than 50 administrative systems but also funding half the cost of the extended benefits that workers receive in times of economic contraction. In 1939, the taxable wage base was $3,000, equivalent to $55,000 in 2020 dollars. Because this amount can only be raised by law (and has only increased three times over the past 80 years), its value has eroded by nearly 800 percent. In contrast, the taxable wage base for Social Security benefits was indexed to inflation in 1977. The chart below shows their divergent histories. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

This trend has been labeled fiscal constriction by Columbia University scholar Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, and it means that by starving the Unemployment Insurance program of resources, policymakers effectively bind their own hands and purposefully prevent themselves from establishing a modern and efficient system for disbursing benefits. During the Great Recession, we saw the consequences of fiscal constriction clearly. Yet federal policymakers left the taxable wage base at the same level it has been stuck at since 1983, unmoved by the hardship of millions of members of the U.S. labor force and unwilling to risk even a small amount of political capital by modestly nudging tax levels upward.

Bringing the Unemployment Insurance taxable wage base back to the same level as the Social Security taxable wage base and then indexing it to inflation would provide states with the resources they need to deliver unemployment benefits efficiently and effectively.

Looking to 2017 as an example and conducting a simple back-of-the-envelope calculation that keeps the FUTA tax rate at 6 percent and applies a 5.4 percent state credit reduction to the $7 trillion of taxable earnings under the Social Security wage base indicates that using this tax base would generate $41 billion. This is a $33 billion increase over the $8 billion in FUTA taxes that were actually collected in 2017. Similar to other social insurance programs, Unemployment Insurance has an elegant design—small taxes in good times ensure smooth delivery of benefits in hard times. By allowing the pay-for to erode over time, policymakers shirk their fiscal responsibility, and workers and families pay the price. Following the Social Security model and indexing the wage base is a small investment that will yield large dividends.

In fact, this additional revenue would provide sufficient funds for Unemployment Insurance system modernization efforts (past grants to states have ranged from $50 million to $200 million), ongoing maintenance, and appropriate staffing. These funds also could be used to provide grants to states to partner with community-based organizations serving vulnerable workers to raise awareness of Unemployment Insurance benefits and provide assistance in the application process. Additional revenue would cover the increased use of the Extended Benefits program and could be used to provide grants to states as they standardize the amount and length of benefits, as detailed below. Any change to the taxable wage base could be scheduled—for example, occurring when unemployment rates return to pre-pandemic levels with revenue advanced prior to that time.

Without this type of policy change, policymakers won’t have the resources that are so badly needed to repair our broken plumbing and efficiently deliver benefits to people who are entitled to them under law. The case of Unemployment Insurance shows that it’s not enough to build a system to disburse benefits—that money needs to be spent over the long haul to maintain that system. This type of continued investment is necessary to deliver the benefits that provide relief to individuals and stabilize our economy when crisis hits.

Direct payments to households—plumbing that twists and turns to allow siphoning off along the way

Most Americans live on razor-thin budgets, even in good times. One study from the Federal Reserve has found that only 40 percent of Americans could cover a $400 emergency expense.

So, when Congress authorized emergency direct payments to households as part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act, the efficiency of the plumbing was nearly as important as the amount of water unleashed from the aquifer. The degradation of our public plumbing systems—namely, the IRS as an agency tasked with locating all U.S. taxpayers and building a channel to allow payments between individuals and the government—was laid bare.

While around 6 in 10 people who file taxes received a direct deposit refund from the IRS in 2018 or 2019—the filing years the IRS used to track bank account information for these payments—4 in 10 filers, representing almost 64 million filers, did not (the vast majority of those 64 million filers was eligible for CARES Act payments, which phase out for higher-income earners). These individuals and families had to wait weeks for paper checks to be mailed, with one estimate suggesting that certain filers may have to keep waiting until September, about 20 weeks after the direct payments were authorized by Congress. While the IRS rightly prioritized mailing checks out sooner for those with the lowest adjusted gross income, mailing paper checks still took weeks longer than for those with direct deposit numbers on file.

Those who don’t file tax returns with the IRS faced an even more complex situation. Social Security recipients who didn’t, in the recent past, file tax returns received unclear information about whether they had to file a supplementary tax form to get a direct payment check and had to meet a deadline if they wanted to claim dependents. While the IRS set up an online portal for nonfilers to report direct deposit information and avoid the check-mailing process, the deadline for such submissions was May 13, and many less-tech-savvy individuals probably didn’t know where to enter that information or were unable to do so.

While the IRS worked as quickly as possible to deploy money in a timely manner, there are consequences to this lack of preparedness. Those who receive paper checks may have needed, or may still need, to get expensive payday loans to tide them over until checks arrive. Others still may overdraft on their bank accounts, leading to fees. Others who don’t need an advance on their checks may need to go to expensive check cashers to convert checks into money once they arrive. And because policymakers allowed creditors to “eat first” once checks arrived, stories surfaced showing that banks garnished the checks deposited into peoples’ accounts, both to repay bank debts and on behalf of debt collectors.

All told, direct coronavirus-payment challenges replicate our existing understanding of the high cost of being poor, with low- to moderate-income households spending far more than other households on fees as a percentage of their income, averaging a whopping 10 percent of income, using data from before the coronavirus.

These expenses reflect a lack of public economic infrastructure. And while they represent burdensome budget items for some, they represent profit to others. Banks made an estimated $11.68 billion in overdraft fees in 2019, with an average fee of around $35 per overdraft. These fees fall particularly hard on the working class, with only 9 percent of account holders (typically those with low account balances) representing 84 percent of the total fees charged. Check cashers and payday lenders made a similar amount in fees, totaling around $11.4 billion in 2019.

Further, the tax preparation company TurboTax, owned by Intuit Inc., created a proprietary website where individuals could go to enter direct deposit information, calculate anticipated check amounts, and check on the status of their payments. While the website services are offered at no charge, TurboTax has, in the past, used the promise of free services to steer filers into more expensive proprietary and add-on products, even when they qualified for free filing. TurboTax made $1.6 billion in income in the most recent filing year.

Solutions for quicker direct payments

All of these frictions were avoidable had other public policy choices been made. Just as fiscal constriction has hobbled state Unemployment Insurance systems, federal policy has deliberately underinvested in technical capacity and potential delivery systems for the IRS. While the IRS staff had an unenviable task of accomplishing the massive technical and logistical challenge of deploying millions of direct payments in a matter of weeks during a global pandemic, the snafus experienced by the agency were undoubtably made worse by sustained budget cuts over the past decade. As the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities documents, the IRS has lost nearly 15 percent of its staff and 21 percent of its budget since 2009. A more well-resourced IRS would have been better prepared for this moment.

Policymakers also missed an opportunity to build out the IRS’s technology infrastructure by not considering legislation to direct and support the IRS in establishing a free file online portal system for annual tax returns. Though envisioned as a tool for routine annual filings before the pandemic, such a system run by a well-resourced IRS could have been quickly repurposed to meet direct payment needs and could have supplanted TurboTax.

Moreover, policymakers could have advanced other actions to strengthen payment delivery mechanisms to individuals and households. The United States has one of the slowest payment systems in the world, compared to peer countries. This means that it can take days after funds are deposited in private bank accounts for those funds to actually be available to spend. Again, in the case of the coronavirus recession, this adds yet more frictions to the delivery of aid. But this slow system is not inevitable.

In the United States, the Federal Reserve both regulates the private payment system and operates its own system. The private payment system, which is the dominant system, is operated by The Clearing House, a consortium of 24 large banks. The Fed has long had the goal of modernizing its own payment system, which hasn’t been updated in decades, releasing a proposal to bolster payment infrastructure in 2013 and then committing in 2019 to finalize an upgraded payment infrastructure by 2024.

Such moves to modernize our public payment infrastructure have been opposed by The Clearing House. The bank association argues that large banks have already invested substantial time in building their own system, that the Fed cannot act as both a regulator and a competitor, and that further investments would be needed to ensure interoperability with the new Fed system. Below the surface are the obvious concerns that this public system would undercut The Clearing House’s market dominance, would reduce profits on payment transactions, and would dampen the use of overdrafts, thereby further reducing bank fees.

In the case of the deployment of coronavirus rescue funds, a public, faster payment system would have clear benefits. One estimate from Aaron Klein, policy director for the Center on Regulation and Markets at The Brookings Institution, finds that implementing the Fed’s real-time payment system could save low-income families $7 billion a year simply by helping money to arrive faster and allowing families to thereby avoid intermediaries such as check-cashing services and payday lending companies to access their money.

Further, a public payment system also would help small businesses to manage incoming and outgoing payments, as these businesses are now operating on thinner margins during the recession. Lastly, a faster digital payment system is essential during a highly transmissible pandemic. While the use of cash to make payments has been declining for years, public health concerns and social distancing have increased the need to more quickly mediate money electronically.

In addition to building a quicker public payment system to deliver funds to private bank accounts, policymakers also could build accounts that are themselves public. Legislation based on the work of Washington Center for Equitable Growth Board member Mehrsa Baradaran has, for years, been introduced to allow the U.S. Postal Service to provide basic banking services to customers—bank accounts that could be available in every community across the country and could allow for a functioning economic system that equitably serves all individuals and families.

In this way, policymakers could eliminate or reduce costly fees and stop garnishments through this public system. And it wouldn’t be a new or untested approach. The U.S. Postal Service has done this in the past, providing banking services for 50 years starting in 1911. This would have the benefit of both expanding access, reducing costs to consumers, and shoring-up the finances of the postal system, which stands in a precarious position due to both the pandemic and congressional legislation that has required the service to pre-pay 75 years’ worth of healthcare and retirement benefits for workers. The Postal Service could offer these accounts either through a congressional authorization or via administrative action, with its Board of Governors authorizing the measure.

Paid leave—when plumbing does not exist

If ever there were a moment that called for paid leave, the coronavirus crisis is it. The term “paid family and medical leave” refers to social insurance programs in which a small payroll tax is collected while people work and then—when the need arises to care for a new child, seriously ill loved one, or one’s own serious medical need—workers can take weeks or months away from work with partial wage replacement. In some thoughtfully designed paid leave programs, workers are guaranteed to be able to return to their job when their leave is complete.

Most paid leave programs were not designed with a pandemic in mind, but they are built to deliver paid time away from work for health reasons while maintaining attachment to one’s employer. If you are scratching your head and wondering why policymakers chose not to deliver payments through a small modification to the eligibility criteria associated with our federal paid leave system, the answer is simple: We do not have a federal paid leave system. Legislation has been introduced for many years that proposes the adoption of a federal paid leave program. Yet political obstacles have prevented us from establishing a federal system, despite the research that suggests doing so would strengthen the economy and benefit the finances and health of paid leave claimants and those who receive care from them. A lack of a federal system leaves us scrambling to provide paid leave solutions when workers need them most.

Congress eventually passed legislation in response to the employment crisis caused by the COVID pandemic. But the “paid leave” program it enacted bears little resemblance to a strong social insurance system that provides adequate time away from work to care for oneself or a loved one. This is a temporary stop-gap, not an investment in permanent plumbing. This stop-gap system provides a fraction of the workforce with 80 hours of leave at full pay for those with symptoms or the need to quarantine due to one’s own COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, 80 hours at two-thirds pay for to care for someone subject to quarantine or a child subject to COVID-19-related school or childcare closure, and another 10 weeks of leave at two-thirds pay to provide childcare for one’s own children who are subject to COVID-19-related school or childcare closure. These benefits don’t provide the support that social insurance programs offer and that people whose families are affected by COVID-19 need: weeks, not days, of leave to attend to one’s illness or the illness of loved ones.

While the benefit is not generous enough, the real problem is program administration. The first problem is the glaring issue of the program coverage. Despite the largest firms having the greatest financial and staffing flexibility to allow for leave, no person who works at a firm with 500 or more employees is eligible for leave. Employers with fewer than 50 employees, too, can easily opt out, as can firms that employ healthcare workers or emergency responders.

What’s more, the interpretation of the healthcare carve-out is broad—anyone who works at a healthcare facility, from janitors to accountants, can be carved out. Sarah Jane Glynn at the Center for American Progress finds that as few as 1 in 5 private-sector workers may end up eligible for paid leave.

Then, being eligible for a benefit does not mean that a person can access it. Many factors influence what social scientists call the “take up” of benefits. Key factors include program knowledge, the ease or difficulty of applying for or being granted access to a program, and—in many cases—employer behavior that encourages or impedes claims. When it comes to the newly implemented federal paid leave program, there is a perfect storm of factors that create leaky plumbing. Money that Congress intended to channel to men and women who need time off from work due to COVID-19 is not reaching them in part, it appears, because of the lack of a robust public awareness campaign. Given that most people in the United States do not have access to state-provided paid time off and thus are unfamiliar with the concept, raising awareness of the new program is extremely important—and extremely difficult in the context of the pandemic.

To extend the plumbing metaphor: If people don’t realize that new taps have been installed, they can’t access the water that flows from them. It’s best to install the taps at times when people’s attention is not divided, so that they are aware of them well in advance of when they need to access them.

There is another major reason that we hypothesize depressed paid leave take-up rates: the confusing process of benefit reimbursement. Employers are required to cover the cost of the leave upfront and then are reimbursed quarterly for these costs. This complex way of paying for benefits means that employers who do not want to deal with paperwork or who cannot afford to front the cost of paid leave have an incentive to discourage employees from accessing their right to paid leave and may confuse employees who would otherwise hope to access the benefit.

When workers come to states with questions about their right to access paid leave, state labor departments are hamstrung: They don’t enforce the law, even though state residents come to them with issues. Good state-federal coordination is difficult to develop quickly, but it is crucial to ensure that workers can access the benefits they need. In the absence of a pre-existing plumbing system, workers were left with a temporary and unsatisfactory fix.

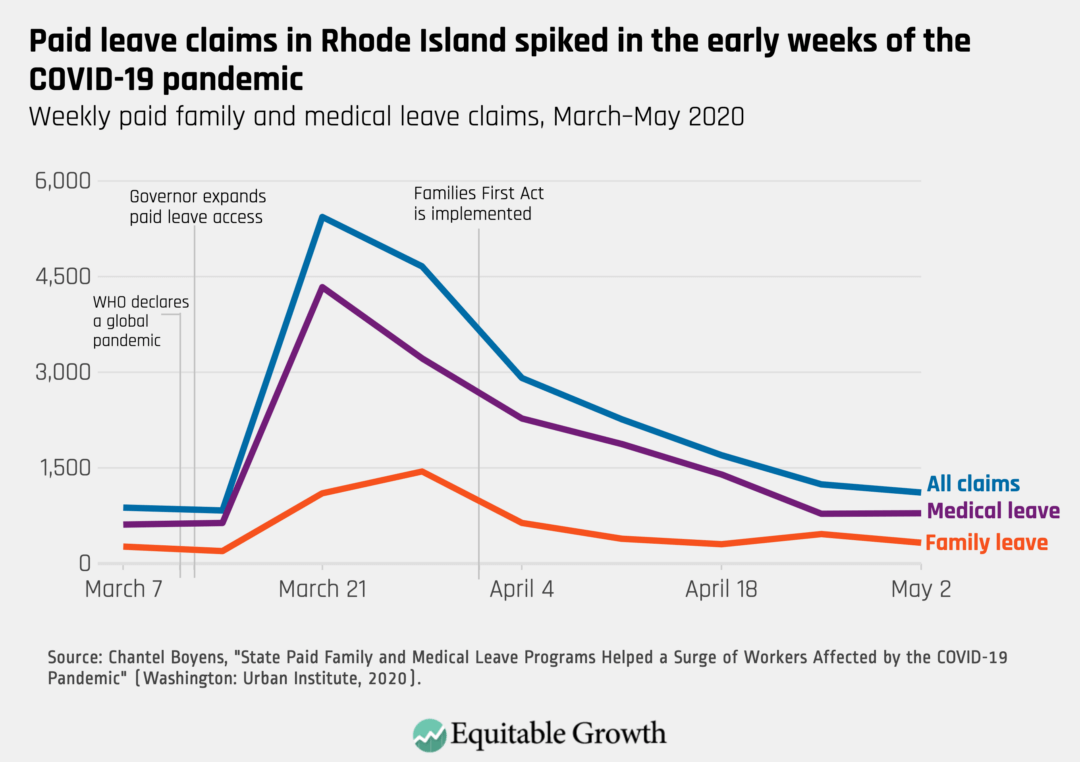

State paid leave systems provide a clear illustration of what a federal paid leave system could have provided, had it been established. When the coronavirus pandemic hit U.S. shores, residents of five states had access to state paid leave programs. In Rhode Island, shortly following Gov. Gina Raimondo’s (D) declaration of a public health emergency, the governor worked with the state’s Department of Labor and Training to ensure that people affected by the pandemic could access paid leave. The result: Paid leave claim rates in Rhode Island shot up in the early days of March. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Because an existing social insurance program was already in place, Rhode Islanders were able to access paid time off when they needed it most. The plumbing was in place to deliver the needed assistance. In contrast, residents of the 45 states that lack paid leave programs waited as Congress debated how to best deliver aid, ultimately receiving a program that missed the mark for effectively delivering paid leave to those who needed it most.

If the federal government had had a strong benefit delivery system in place before the coronavirus pandemic hit, then the benefits that are needed would be flowing much more easily and efficiently. In the wake of this catastrophe, some policymakers are calling for a permanent fix—a federal social insurance program—so that our nation is not caught off-guard the next time a crisis hits.

Conclusion

To break the current cycle of economic contraction and prepare to do so again in the future, policymakers need to deliver benefits to workers and families so that they can pay their rent, fill their prescriptions, and keep food on the table—setting into motion the virtuous cycle of economic stabilization. This moment requires an unprecedented scale of investments in people and businesses in the United States in order to mitigate the pain caused by this economic recession.

But our programs are only as effective as the plumbing we use to distribute those resources in a timely and equitable manner. Systematic disinvestment in our economic infrastructure impaired the well-being of the people in the United States, particularly those who are most vulnerable even in normal economic times. Policymakers’ decisions to allow, or even hasten, the degradation of economic infrastructure is a choice, not a coincidence. Our faulty plumbing has been purposefully neglected, poorly constructed, and designed in the service of short-term profits for some and as a backdoor way to deny aid to the most disadvantaged members of society.

To stabilize our economy in times of macroeconomic contraction, we need to redesign our invisible economic infrastructure to more quickly help individuals and families, not just the most well-resourced, eliminate costly toll collection from financial intermediaries, and reinvest in durable plumbing to prepare us for the next drought.