April Jobs report: Disappointing job gains mean the damage from the coronavirus recession may be long term, especially for young workers

The U.S. labor market delivered employment gains that were far below expectations last month. According to the Employment Situation Summary released this morning by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, between mid-March and mid-April the U.S. economy added only 266,000 non-farm payroll jobs, and the share of the population between the ages of 25 and 54 that is employed—a measure economists call the prime-age employment to population ratio—increased only slightly, from 76.8 percent in March to 76.9 percent in April.

April’s Jobs report is a stark reminder that the U.S. labor market continues to be a long way from its pre-pandemic employment levels. The U.S. economy now has a jobs deficit of 8.2 million compared to February, 2020, before the coronavirus pandemic and resulting recession hit. For the millions of workers who have lost their jobs, including many young workers and those who experienced structural disadvantages in the labor market well before the coronavirus recession, this crisis may lead to long-term damage to their economic outcomes.

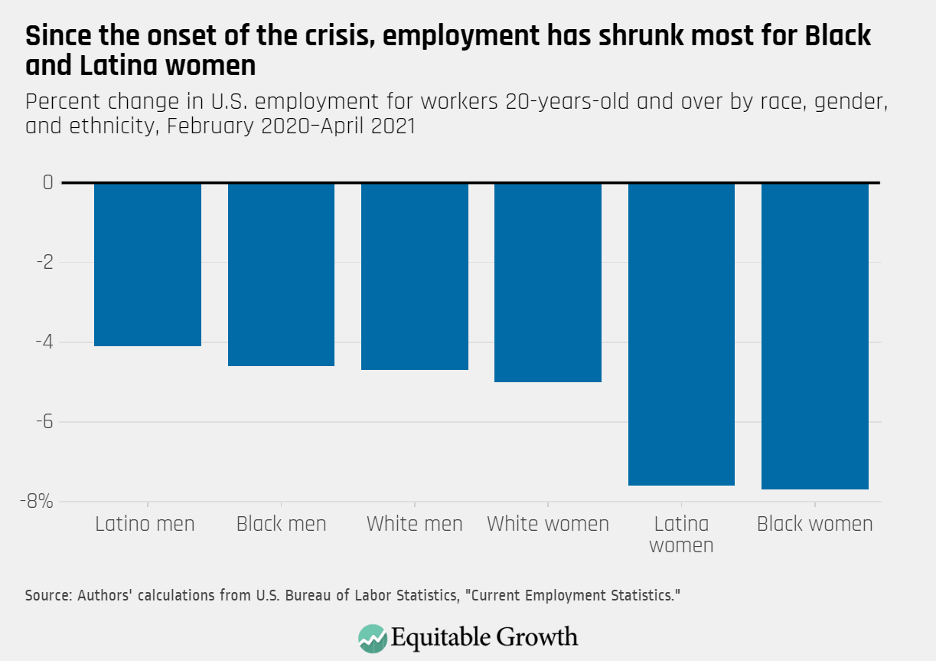

The modest net increase in employment was not spread evenly across the workforce. At 9.7 percent, the unemployment rate for Black workers is higher than for any of the other major racial or ethnic groups, followed by the jobless rate of Latinx workers (7.9 percent), Asian American workers (5.7 percent), and White workers (5.3 percent). Across race, ethnicity, and gender, Black women saw an important increase in employment, adding 135,000 jobs. Yet the number of Black women employed is still 7.7 percent below pre-coronavirus recession levels. Along with Latina women, Black women’s employment has declined more than for any other group. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

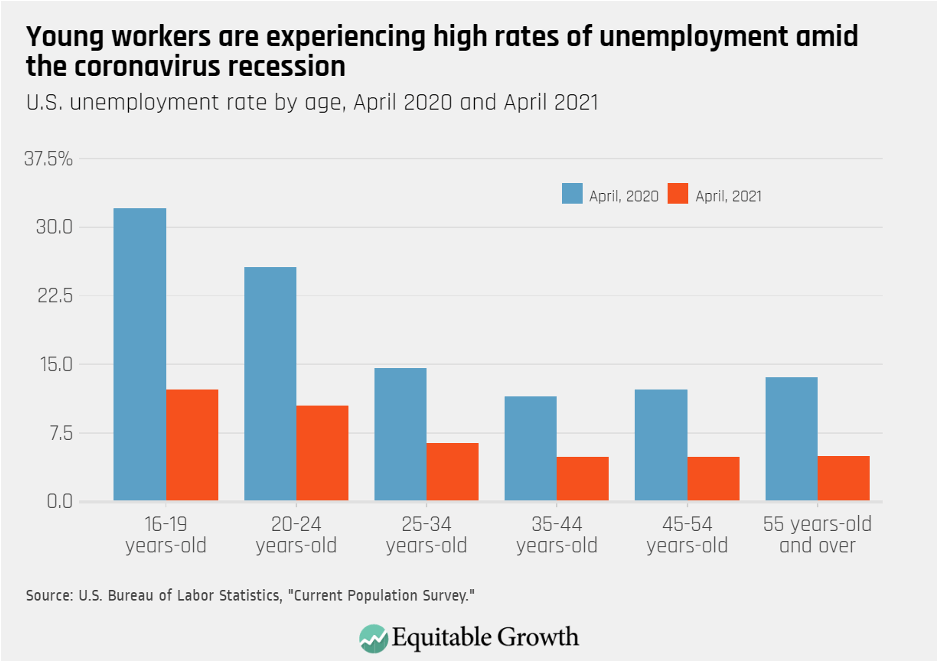

Young workers are another group that has been hard hit. As the health and economic crises hit the United States, the unemployment rate of workers between the ages of 16 and 19 skyrocketed, going from 11.5 percent in February 2020 to 32.1 percent in April 2020. For workers between the ages of 20 and 24 the jobless rate climbed from 6.3 percent to 25.6 percent during the same period. Currently at 12.3 percent and 10.5 percent, respectively, the jobless rate for the youngest subsets of workers in the U.S. economy is both above pre-pandemic levels and above the jobless rate of older workers. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Research from the early months of the coronavirus recession shows that younger workers—along with workers of color, workers with lower levels of educational attainment, and women workers—experienced both particularly large decreases in hiring and particularly large employment losses. These results hold even when accounting for young workers’ occupational distribution, since they are overrepresented in positions that have been among the most exposed during this downturn, including lower-paying service jobs in the leisure and hospitality industry.

Moreover, at the height of the recession last spring young Black, Asian American, and Pacific Islander workers experienced especially high jobless rates, reaching nearly 30 percent according to an analysis by the Economic Policy Institute, compared to 24 percent among all workers between the ages of 16 and 24.

What makes younger workers so vulnerable to slack business conditions? For one, research shows that workers who first step into the U.S. labor force during a recession experience persistently harmful effects on their future labor market outcomes. Usually, early careers are periods of strong earnings growth—a process that can be disrupted by recessions. In addition, because earnings mobility has declined since the 1980s, where workers start off in the earnings distribution is increasingly important.

Research by Jesse Rothstein at the University of California, Berkeley, finds, for instance, that workers who graduated college during the Great Recession of 2007–2009 had lower employment rates and earnings than older college graduates. Likewise, research by Kevin Rinz of the U.S. Census Bureau shows that during the Great Recession, millennials (people born between 1980 and 1994), experienced especially large earnings losses that persisted even as the U.S. economy recovered.

In part, Rinz finds, these losses were driven by millennials’ lower likelihood to work for high-paying employers even as their employment rates recovered. Rinz also finds that millennials suffered from structural changes to local labor markets in hard-hit locations that caused persistent lower earnings and employment opportunities even as the overall national economy moved beyond the recession.

As the U.S. economy struggles to return to pre-pandemic levels, it is important to highlight the persistent negative economic consequences facing the hardest hit workers that could last well into the forthcoming economic recovery and exacerbate long-term trends of rising economic inequality and insecurity. A year after one of the worst months for the U.S. labor market, an important way to prevent young workers from the harmful long-term consequences of recessions is to promote healthy earnings growth through policies that increase wages, such as lifting the federal minimum wage floor and fostering unionization to offset the persistent downward pressure on wages facing these workers.

To ensure that happens, policymakers should make heavy long-term investments in the broader U.S. economy alongside economic relief to workers and families and greater access to Unemployment Insurance benefits to give affected workers a strong and stable foundation to build on during the eventual recovery. Specifically, under the current Unemployment Insurance system, self-employed workers, workers just stepping into the labor force, and workers who do not meet the minimum earnings thresholds are not eligible for regular jobless benefits, hurting both individual workers and the entire economy. To ensure the damages caused by the coronavirus recession can be overcome swiftly and sustainably, all young workers and other vulnerable workers need to be able to benefit from one of the country’s most important income support programs.