What makes a job ‘good’? How U.S. labor market data can provide insight to improve workers’ economic conditions

Since the Great Recession of 2007–2009, a great deal of U.S. economic policymaking has been dedicated to creating jobs. The tools used to do so vary widely, from awarding grants or contracts to companies for the production of goods or the provision of services to providing financial support for households whose spending drives commerce and creating tax and regulatory conditions that are conducive to business investment.

Successfully creating jobs is seen as a political asset, while failure is often seen as a political liability. Indeed, creating jobs is so important for politicians’ future electoral outcomes that the first Trump administration presented its signature policy achievement—a tax cut that predominantly benefitted corporations and high-income individuals—as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, even though the unemployment rate was at a low rate of 4.1 percent when the law passed in December 2017. Similarly, Congress passed the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in November 2021, when the unemployment rate was 4.2 percent.

In a sense, it is reasonable for policymakers to be very focused on jobs. A large majority of people earn their incomes predominantly by working, and voters routinely list economic issues among their top concerns. And during the prolonged recovery from the Great Recession, there was a clear connection between creating jobs and improving people’s economic standing: At the time, there were not enough jobs available for everyone who wanted one.

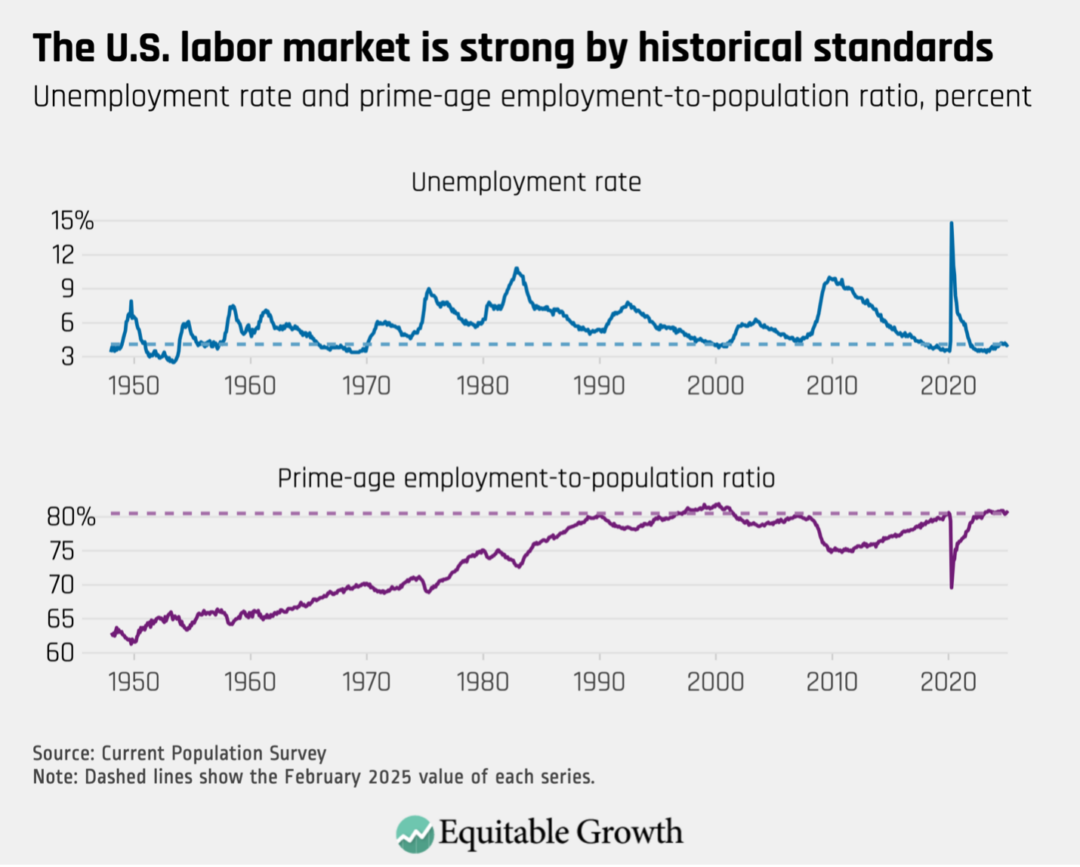

But nowadays, far fewer potential workers are on the sidelines, and it is much less clear how simply creating jobs might translate into higher standards of living. As at the end of 2017, the U.S. unemployment rate is currently 4.1 percent, and more than 80 percent of adults ages 25 to 54—the group of workers who tend to be most attached to the labor force, also known as prime-age workers— are employed. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

When such a large share of people who want jobs already have jobs, the workers who ultimately take a newly created job are probably those who already had a different job doing something else. As such, the economic improvement for these workers is more incremental than the gains that would be made by someone moving from unemployment to employment.

This diminished ability for newly created jobs to materially improve well-being represents a challenge for policymakers. Many of their constituents remain frustrated by their economic circumstances. Making them better-off therefore requires improvements in not the quantity of jobs available but in the quality of jobs available.

To their credit, policymakers have not neglected job quality. Recent and ongoing conversations about industrial policy in the United States are partially driven by an interest in improving job quality. The Biden administration, for example, took a range of steps to promote high wages and widen access to benefits in jobs connected to investments made through legislation such as the CHIPS and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act.

When the government controls or influences the terms of employment, focusing on what a job delivers concretely to a worker in terms of pay or benefits is a reasonable way to think about job quality. But the government cannot simply require that jobs be good. A job that pays well today may disappear tomorrow, and the best jobs a decade from now may not even exist yet.

Understanding the content of jobs—the tasks workers do, the skills they develop, and the abilities they rely upon to complete their work—in a more granular way, how that relates to compensation, and then how those things have changed over time can provide broader insights into many questions policymakers have about job quality. Which jobs are good now? Which jobs might get better or worse in the future? To what extent does access to good jobs differ across groups of workers?

Considering job content also can help policymakers think about the fundamental question underlying all of those specific questions: What makes a job good?

To that end, over the next few months, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth will be publishing a series of columns that will analyze various aspects of the relationships between the skills and abilities jobs require, the activities they involve, and the wages workers earn doing them.

We will draw information about the content of jobs from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Information Network, or O*NET, which has published detailed data on approximately 1,000 occupations in consistent form since 2003. While O*NET is not among the labor market datasets most widely used for research purposes, these data have been critical to studies that have shaped our understanding of how the labor market has evolved in recent decades. O*NET data also are emerging as an invaluable resource for analyzing the impact of artificial intelligence on the U.S. workforce.

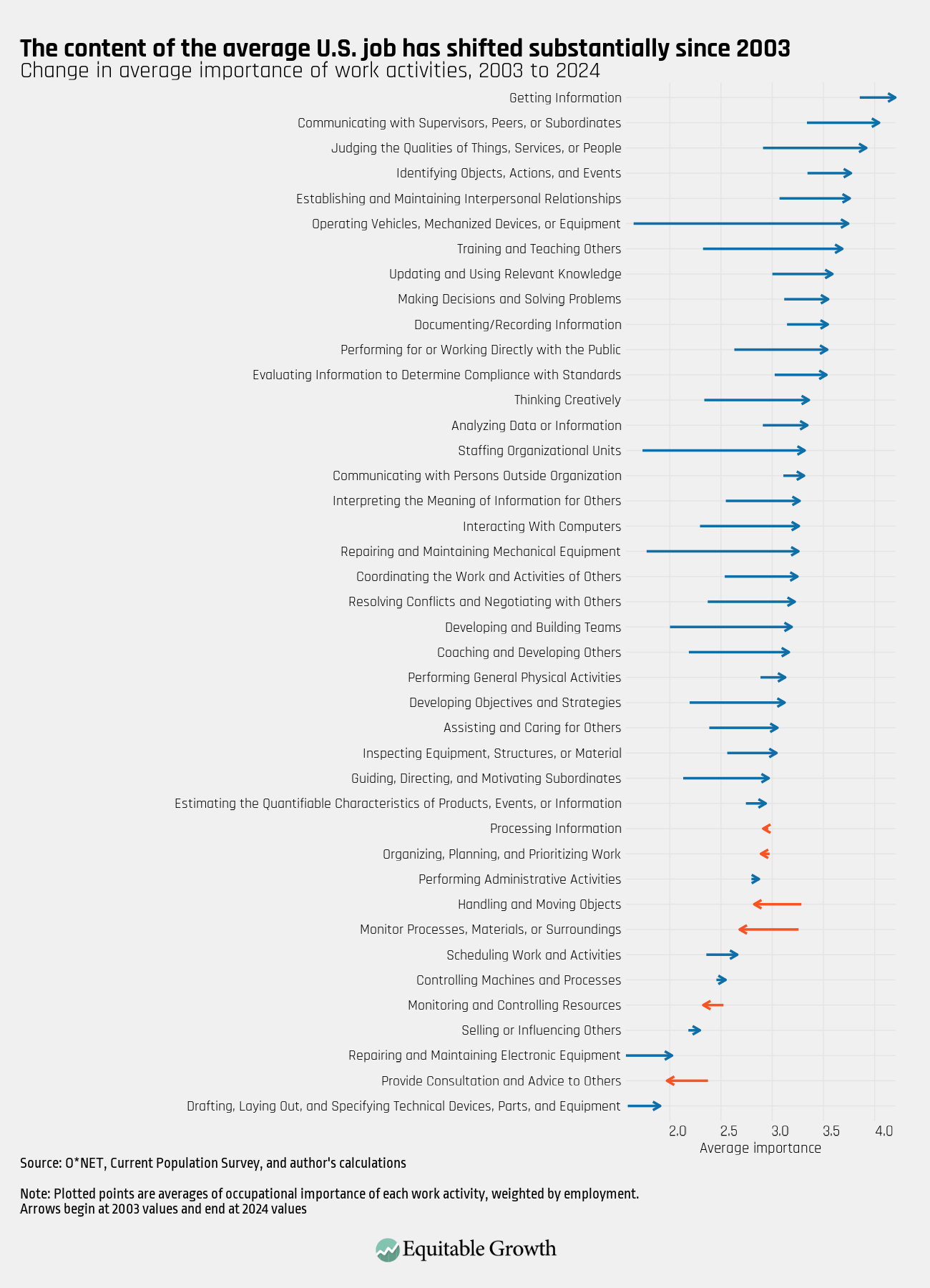

O*NET data can reveal a lot about job quality and job content in the United States. By consistently measuring detailed characteristics of jobs across the 1,000 occupations it surveys, O*NET data can help reveal changes in the U.S. labor market that would be missed if occupational titles were the only input studied. For example, Figure 2 below shows the average importance (on a scale of 1 to 5) across all surveyed jobs of 41 work activities in 2024, as well as how each activity’s importance has changed across all jobs since 2003. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

As we can see in Figure 2, a number of activities have experienced substantial shifts in their average importance over the period measured. This has happened even without large shifts in employment in jobs that may be most associated with those activities. For example, operating vehicles, mechanized devices, or equipment saw the largest increase in importance since 2003, from an average of about 1.6 in 2003 to about 3.7 in 2024. Of the major occupational categories, this activity seems most intuitively aligned with production, transportation, and material-moving occupations. Yet jobs in this category did not become correspondingly more common over this period. In fact, they declined as a share of total employment.

In the coming months, Equitable Growth will use O*NET data to tease out insights about how the tasks people do and the skills they use at work matter currently, how those developments came about, and what that means for the future of work and the U.S. labor market. This lens can be helpful for thinking through which jobs are good and how to make other jobs better—both of which are essential for policymakers and employers alike as they navigate changes to the labor market and labor force in the United States.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!