Weekend reading: The fate of child care and of small businesses in the post-pandemic economy edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

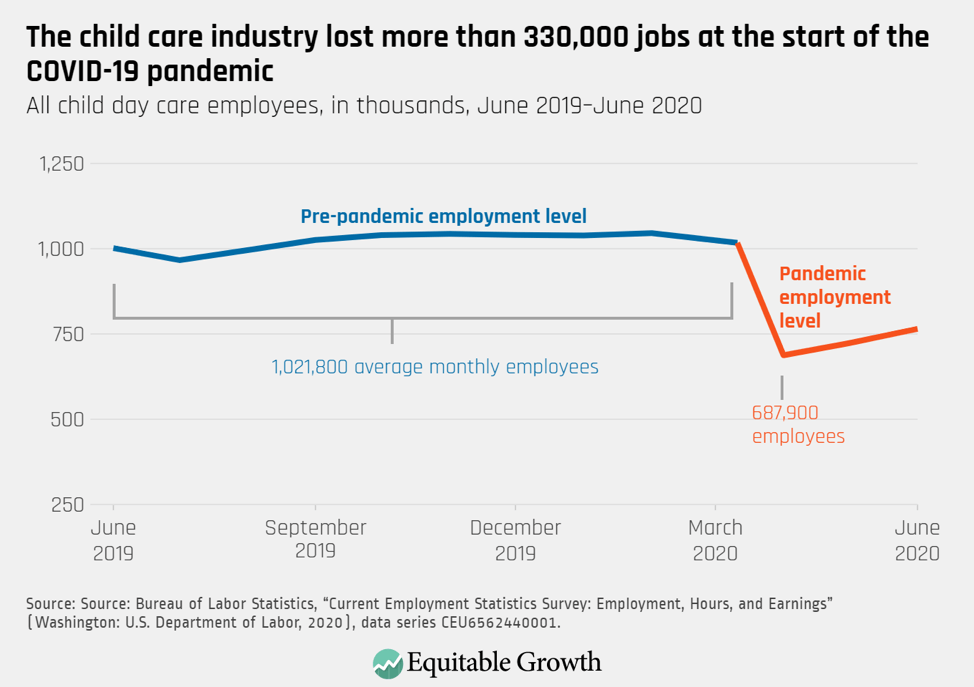

The coronavirus recession and the current debate surrounding reopening the U.S. economy shine a blinding light on the role of child care in supporting our economy. In fact, writes Sam Abbott, rarely before has it been so obvious how important various forms of child care—from schools to daycare to summer camps—are to the state of the economy and its ability to recover. A national set of safety standards must be developed by scientists and public health officials, he argues, and until that happens any plans to reopen schools and child care facilities will remain patchwork and random, shaped largely by uncertainty about the coronavirus pandemic and its impact on children and how it is spread by children. Likewise, Abbott says, policymakers should ensure that child care is affordable and accessible to all American families—an already daunting challenge made more formidable because the child care industry has suffered devastating layoffs and closures since the onset of the pandemic. Abbott reviews some pre-coronavirus trends in child care options and parental preferences, and why those choices could limit the post-pandemic child care industry without thoroughgoing reforms.

Now that some U.S. small businesses are attempting to reopen, and policymakers are still considering how to stabilize the economy while protecting public health, it is as good a time as any to look back at the Paycheck Protection Program and examine its efficacy in achieving its goals. The program was designed to help small businesses keep employees on payroll and avoid bankruptcy during the pandemic. While early research shows it did provide a liquidity backstop for some firms during lockdowns, Amanda Fischer explains that studies also show that PPP loans did not go to small businesses in the country’s hardest-hit areas and that the program itself did not have a statistically significant impact on preventing layoffs. Fischer goes through the various studies that analyze the program and reveal its flaws, and then proposes several policy recommendations and alterations that could address these shortcomings in future iterations of the program.

New research from Kate Bahn and Mark Stelzner shows how employers have more power over—and thus can push wages down more—for women and non-White workers compared to White men workers. The co-authors look at how workers search for jobs to show how racial and gender wealth disparities reinforce discriminatory pay penalties. They find that workers with greater wealth (who, in the United States, tend to be White workers) are better equipped to weather drops in income levels during job search periods and can thus hold out for a job that pays well and fits their skillset, while workers with less wealth and less of a financial cushion (who tend to be workers of color) take jobs that pay “just enough” out of necessity. Similarly, women workers tend to have more household responsibilities and thus are constrained by geography in their job searches, reducing their job prospects and allowing employers to take advantage of that constraint. The co-authors also show how workers’ ability to act collectively limits employers’ monopsony power, or the ability to set wages, of employers and reduces exploitation of workers based on gender and race and ethnicity. Bahn and Stelzner then propose several policies that can strengthen worker power, reduce wealth inequality, and boost family economic security.

Head over to Brad DeLong’s latest Worthy Reads to get his takes on recent must-read content from Equitable Growth and around the web.

Links from around the web

Until now, there has been very little acknowledgement of how truly vital child care and schooling is to the functioning of the U.S. economy—or the impact a broken child care system has on workers and their families. Vox’s Anna North gives us a deeper look at the numbers, providing an easy-to-grasp framework for looking at the impact of the current child care crisis on our economy and how important it will be to solve this crisis for our future economic recovery. North looks at data points such as the number of workers with children under age 18 who have lost their child care due to the pandemic, the impact of this loss on income, wages, and hours worked, and how differently this affects women and men workers, as well as two-parent and single-parent households. North then reviews the impact of the coronavirus pandemic and resulting recession on the child care system and its workers, and, in looking at the Trump administration’s failure to provide guidance in this area, concludes with an assertion that we must change how we value care work and education in order to carve out a path forward.

Eventually, the overall U.S. economy will recover from the coronavirus recession, but not before leaving a lasting impact on how many Main Streets across the United States are structured, writes James Kwak in The Washington Post. It’s likely that many small businesses will not survive, that “chain stores will replace mom-and-pop businesses, some storefronts will remain vacant, and cash that once went into local hands will be redirected to Amazon and Walmart.” In other words, the pandemic and the resulting recession are likely to amplify the two major trends that have been reshaping our economy in recent years: consolidation and inequality. Kwak explains the effect these two economic trends have had thus far, and how they will only be exacerbated by the hardships many small businesses and local economies are likely to face in the coming months and years.

Before federal aid lapses at the end of this month, policymakers in Washington DC must ensure that Unemployment Insurance benefits are extended until people can actually find new jobs and return to work safely, writes The New York Times’ Editorial Board. Automatic stabilizers would work to increase support for those in need during this and future crises and wind down automatically when normal economic conditions return, the Board continues, thus guaranteeing that politics don’t play a role in helping vulnerable communities facing layoffs. The extended unemployment benefits provided in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act in March have played an outsize role in stabilizing household finances and keeping families out of poverty. The end-of-July expiration date was placed on these extended benefits because policymakers hoped the pandemic would be under control by now. Because this is obviously not the case, the Editorial Board urges Congress to act swiftly to extend these benefits further and incorporate an automatic stabilizing element to ensure workers receive needed aid in the best, smartest, and most timely way.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Child care is essential for working parents, but is the industry ready and safe to reopen?” by Sam Abbott.