Weekend reading: The federal government’s role in the coronavirus response edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Now that Congress has passed the second round of funding for the Small Business Administration’s Payroll Protection Program—which provides loans to small businesses in response to the coronavirus recession—it’s time to look back at the federal government’s handling of the first round and correct its mistakes. Using data on loan sizes and distributions, Amanda Fischer takes us through some lessons that policymakers can learn from the first round of small business funding, which dried up in just two weeks. Fischer explains how existing inequalities may have biased how, where, and to whom the original $349 billion was distributed, leaving big businesses and certain small businesses in specific industries more likely to survive the coronavirus recession than their less-advantaged peers. Fischer calls on policymakers to not only continue passing additional aid for small businesses but also ensure better oversight and data collection into the distribution and allocation of the funding.

Another suggestion for improving federal government intervention in the face of the coronavirus recession comes from Heather Boushey on Medium: bringing back a Great Depression-era Works Progress Administration response. The U.S. economy will not be able to recover unless and until the public feels safe leaving their homes, knowing that the virus’s spread has been contained—and this is unlikely to happen without a great increase in our capacity to test, as well as track and trace individuals who have been infected. Widespread testing and a robust track-and-trace system require federal government intervention to coordinate and implement evenly on a national scale. The federal government is the only entity with the expertise and capacity to do so swiftly, and, Boushey argues, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention could quickly step into this role: It is already trained in infectious disease tracking and knows how to manage privacy concerns around this type of data collection and surveillance.

As Congress refuses to provide additional funding for state and local governments to address the coronavirus pandemic and recession, the Federal Reserve’s Municipal Lending Facility may be what saves many communities across the United States. In an op-ed published in The New York Times this week, Claudia Sahm argues that the Fed’s unlimited ability to print money and backstop the short-term municipal bond market—which states use to smooth out revenues but which is facing lower lending rates by investors due to economic uncertainty—may help many communities weather this storm. However, Sahm writes, the restrictions on which communities can access this program often exclude small and midsize cities—including the 35 cities with the highest percentage of black residents—as well as rural areas. The Fed can and should lift these limitations, Sahm concludes, in order to support more municipalities facing dire economic circumstances in the face of congressional inaction.

Looking outside our borders, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, the S.K. and Angela Chan Professor of Management at the University of California, Berkeley, examines the coronavirus recession in European and emerging economies in a column covering his remarks at a March 24 online conference of more than 100 economists. He begins by stating that the pandemic and ensuing recession will affect all countries, despite slight differences in the timing of the onset of both the public health and economic crises and in the responses governments have taken. Gourinchas then runs through the three policy proposals the European Central Bank is considering to assist European countries in need, as well as the specific circumstances and challenges facing emerging economies and how they differ from those faced by advanced economies. While developed nations are dealing with deteriorating public health and economic situations within their borders, he concludes, we can’t leave behind developing nations in the recovery and response: We are all in this together.

Links from around the web

How has the $600 weekly Unemployment Insurance add-on affected workers in each state? Ella Koeze’s interactive in The New York Times looks at how the extra $600 compares to average weekly salaries in each state based on the wage-replacement rate to see where unemployment benefits under the new system will be greater or less than a worker’s normal salary. Koeze also examines how policymakers decided upon the $600 flat figure and how it will affect workers unevenly across regions, depending on factors such as cost of living and unemployment benefit floors and caps in various states.

The new coronavirus pandemic has shown the impact that socioeconomic status has on whether a person gets sick, writes Olga Khazan in The Atlantic, and experts say this could lead to a backlash against the better-off. Wealthier people are more likely to have the ability to telecommute, reducing their exposure to the virus, are less likely to have underlying health conditions, lowering their chances of getting seriously ill, and are more likely to practice social distancing correctly than their worse-off peers. It’s common for natural disasters or other crises to expose these gaps in society—and, as a result, these periods also tend to be “good for workers” as they can create an appetite for long-term social change. But, Khazan asks, will the backlash this time be against corporate CEOs or against the middle class? The answer to that question may determine how the working class views government interventions and who to blame for their socioeconomic circumstances.

Predicting recessions is hard for economists even when the world isn’t facing a global pandemic, writes Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux on FiveThirtyEight. In the best of times, it requires tons of research and often more than a few mistakes—and now, with countries around the world struggling to contain the public health and economic fallouts and all the usual sources of economic uncertainty flipped on their heads, it’s even harder to try to predict how long the downturn will last, what will turn things around, or how quick the recovery will be. Thomson-DeVeaux runs through why it’s so difficult to predict and properly diagnose recessions and recoveries, and how the coronavirus recession is as challenging, if not more so, to map.

Friday figure

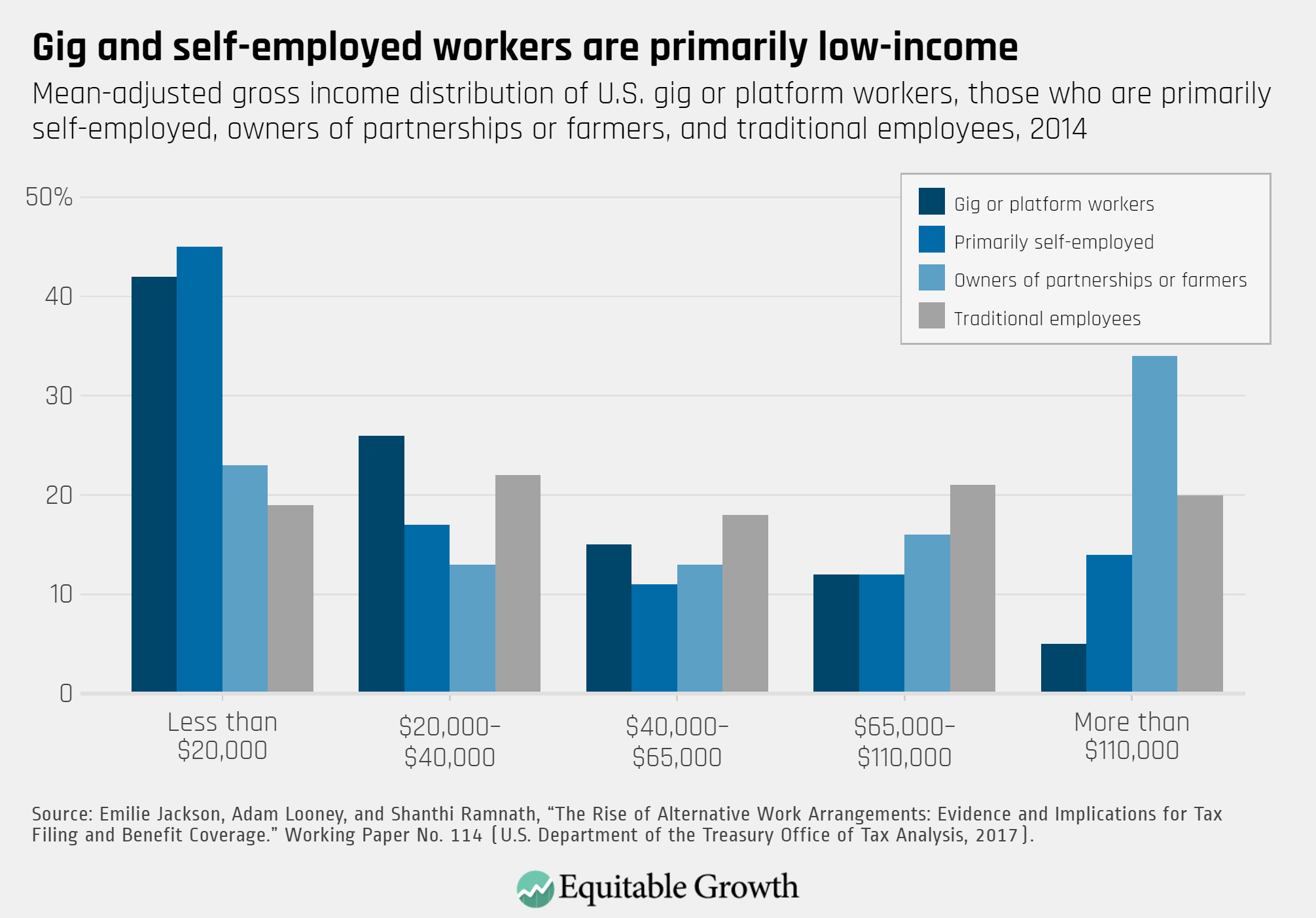

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “The coronavirus recession exposes how U.S. labor laws fail gig workers and independent contractors,” by Corey Husak and Carmen Sanchez Cumming.