The last seven years have been disastrous for many workers, particularly for lower-wage workers with little education or formal training, but also for some college-educated and higher-skilled workers. One explanation is that lackluster wage growth and, until recently, high unemployment reflect cyclical conditions—a combination of a lack of demand in the U.S. economy and greater sensitivity of workers on the bottom-rungs of the job ladder to changes in the business cycle. A second explanation attributes stagnant wages and employment losses to structural changes in the labor market, including long-term industrial and demographic shifts and policy changes that reduce the incentive to work. This explanation interprets recent trends as the “new normal” and suggests that the U.S. economy will never return to pre-recession labor market conditions unless policies are changed dramatically.

My research, based on a review of extensive data on labor market outcomes since the end of the Great Recession of 2007-2009, finds no basis for concluding that the recent trend of stagnant wages and low employment is the “new normal.” Rather, the data point to continued business cycle weakness as the most important determinant of workers’ outcomes over the past several years. It is only in the past few months that we have started to see data consistent with growing labor market tightness, and even this trend is too new to be confident. The continued stagnation of wages through the end of 2014 implies that, at a minimum, a fair amount of slack remained in the labor market as of that late date. In turn, policies that would promote faster recoveries and encourage aggregate demand during and after recessions remain key policy tools.

View full pdf here.

Why is this relevant for policymakers?

Labor force participation rates are still down sharply since the onset of the Great Recession, but the unemployment rate, which spiked from 5 percent to 9.5 percent during the recession, has almost returned to its pre-recession level. If the low participation rate reflects structural economic changes then the current labor market is the “new normal” and there is not much that policymakers can do to improve short-term performance. If instead the problems are due to cyclical economic weakness, generating continued labor market slack that is hidden by the low unemployment rate, then there is much more scope for fiscal and monetary policy to improve labor market conditions. Clearly, cyclical and structural explanations imply vastly different policy responses.

A number of structural shifts have been suggested as explanations for the “new normal,” among them a reduction in workers’ willingness to take jobs (perhaps driven by changes in the incentives created by government transfer programs such as extended unemployment insurance), an aging population that creates shortages of younger workers, and rapid shifts in employers’ needs toward newer types of skills that are in short supply in the labor force. My examination of recent data finds little basis for any of these hypothesized changes. Rather, the evidence—most notably stagnant wages among those who are employed—suggests that lackluster employment growth from 2009 through at least the end of 2014 reflected a continued shortage of demand for virtually all types of workers. It is only in the most recent data—which may well be a temporary blip—that we start to see wage growth consistent with a tightening labor market. It is far too soon to conclude that structural changes will prevent a full recovery to pre-recession labor force participation rates. In the meantime, it will be important to have accommodative fiscal and monetary policies, lest we strangle the belated, still nascent recovery in its infancy. What little wage growth we have seen to date suggests little reason to worry that increases in demand for labor above the current level will trigger meaningful wage inflation.

What do the data say?

The unemployment rate has been below 6 percent since September 2014, lower than many estimates of the level consistent with “full employment.” (Even in a full-employment labor market, we would expect some unemployment as workers transition from one job to another.) Yet the employment-to-population ratio—the share of working-age adults who hold jobs—has been much slower to recover after the Great Recession, and remains lower than was seen at any point between 1984 and 2009. The difference between these measures of labor market slack reflects a sharp decline since 2007 in the share of the population that is participating in the labor market. These declines have continued throughout the recovery, and show no sign of being reversed.

Diagnoses of the situation have thus depended on which data series one chooses to emphasize. The unemployment rate data suggested a robust recovery from early 2011 onward. By 2014, the economy appeared to have little room left to improve, leading some to conclude that the still low employment rate and weak wage growth must have been the “new normal.” But the employment rate series suggested that there remained substantial slack left in the labor market throughout the period as four percent of the population who had been employed before 2007 but were not being pulled back into the labor market. Neither data series in isolation could reveal the true state of the labor market.

To distinguish between these “glass-half-full” and “glass-half-empty” views, I look to evidence regarding employment and wage growth by industry and demography, seeking indications of imbalances between labor supply and demand. If the labor market in 2013-14 was as tight as the unemployment rate alone indicated then we should have seen wage increases as employers bid against each other for workers who were in increasingly short supply. By contrast, if wage growth remained anemic throughout the period, and if employment shortfalls were spread evenly across high- and low-skill demographic groups, then that would be an indication that the unemployment rate was misleading and that the labor market remained quite slack.

View full pdf here.

Findings by industry

One potential source of structural problems is an imbalance between employers’ needs and the skills being offered by job seekers. Rapid technological changes can lead to increases in the demand for workers with specialized skills, yet slack might still remain in other parts of the labor market. There is clear evidence of this sort of imbalance in the mining and logging sector, which has grown substantially since before the recent recession and where there are clear signs that employers are having trouble finding workers to fill open jobs. But outside of this sector, there is little sign that demand growth has been disproportionately concentrated in sectors such as information and technology that typically require specialized skills.

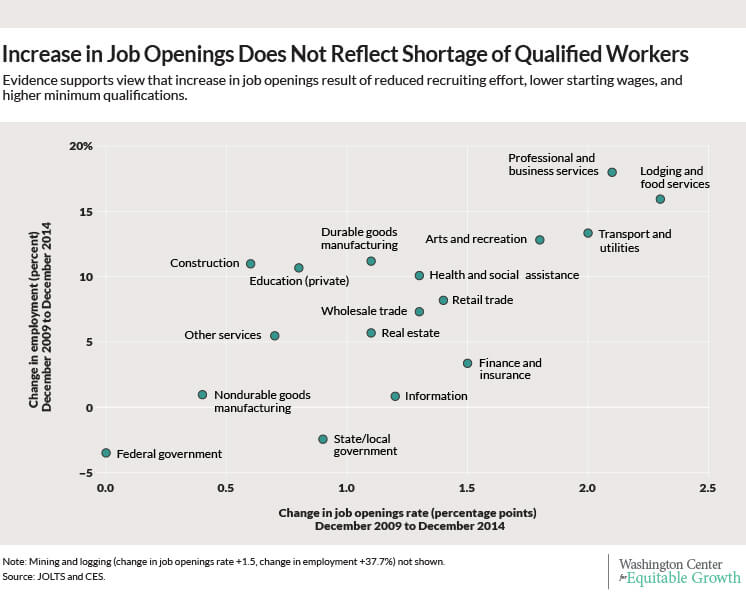

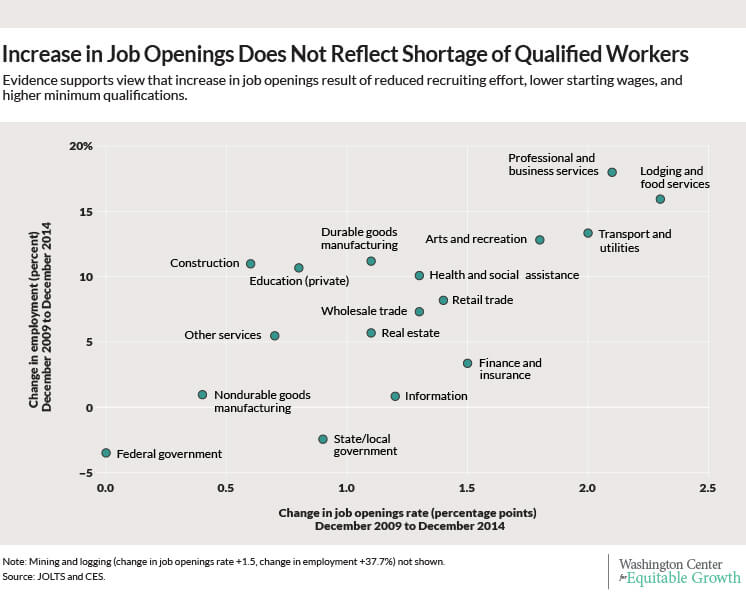

Rather, job openings have grown most in sectors such as transportation, lodging and food services, and arts and recreation. These data generally appear consistent with the view that the increase in job openings reflects reduced recruiting efforts, lower starting wages, or higher minimum qualifications rather than shortages of qualified workers. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

It also is possible that demand for labor within certain industries created shortages of some particular types of workers that are masked by weakness in other subsectors. This explanation is perhaps most plausible for the finance and information sectors, where one can easily imagine shortages of workers with industry-specific skills. The information sector, where technological changes requiring new skills are most likely to be an important component of labor demand, and thus where structural labor supply shortages are most plausible, has had only a modest increase in job openings, and total employment remains below its 2007 level.

Findings by demography

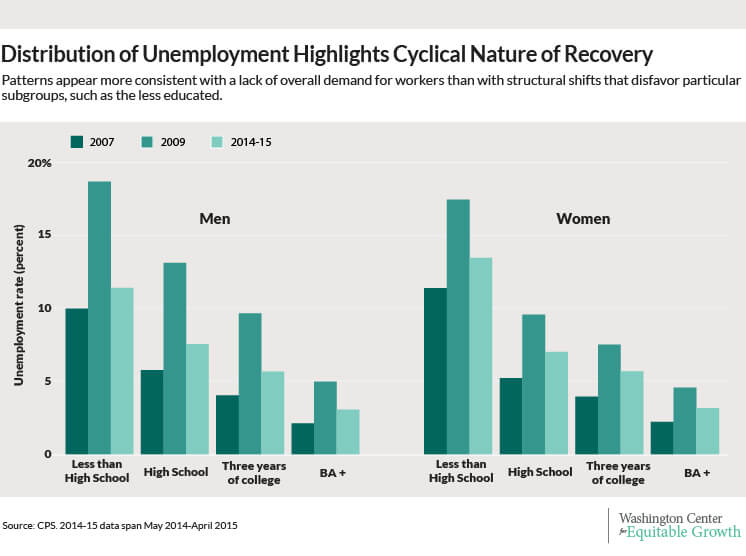

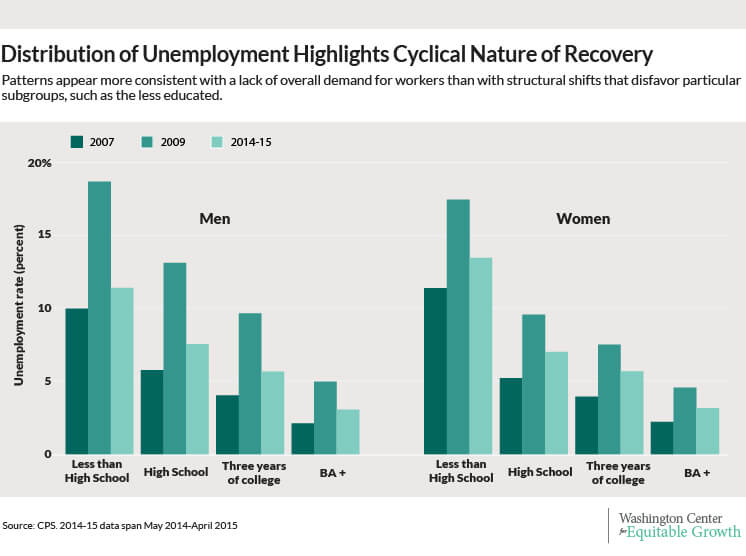

Another source of evidence about mismatches between workers skills’ and firms’ needs lies in the demographic distribution of unemployment. In the recent recession, unemployment rose much more for non-college workers than for those who had attended college, and at each education level more for men than for women. The latter likely reflects the disproportionate declines in construction and manufacturing, which are cyclically sensitive industries that were very hard hit in this cycle. The former could be consistent with a shift in favor of higher-skill workers.

But data from the subsequent economic recovery contradict this explanation. The unemployment rate fell faster in the recovery for less-skilled workers than for college-educated workers, and particularly fast for non-college men. There is no indication that the unemployment rate for college-educated workers has reached any sort of a floor since it remains—even in the most recent data—notably higher than in 2007. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Findings regarding wages

Ultimately, the most decisive way to diagnose the adequacy of labor demand is by examining wages: If employers are having trouble finding suitable workers then they will compete against each other for those workers who are available, bidding up wages. Across-the-board labor shortages would mean increases in wages across the economy while shortages for workers with specialized skills would mean raises in particular sectors.

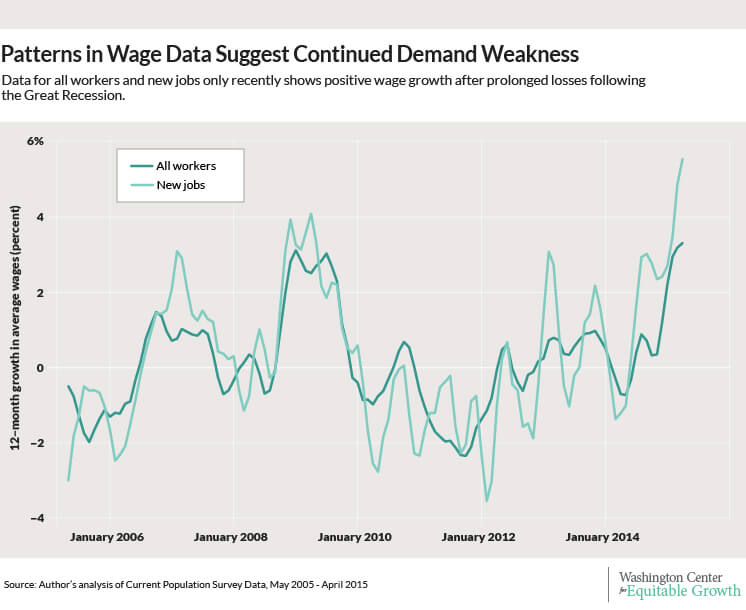

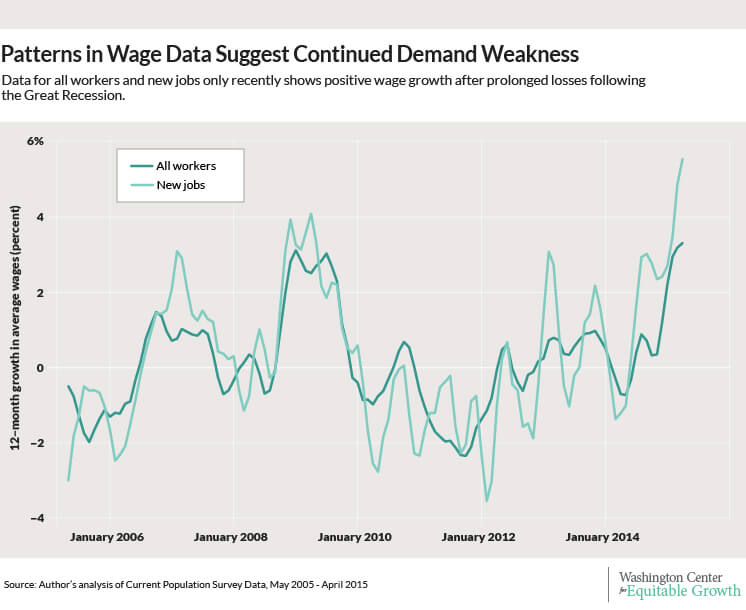

If the economy were pushing against overall limits then we would expect to see rising wages. But the data through 2014 showed no signs of upward pressure on wages. Average real wages (adjusted for inflation) were stagnant since 2009, with increases below 1 percent per year even in 2014. Workers at the very top of the wage distribution saw larger increases, but even these totaled only 2 to 3 percent between 2008 and 2014, and they were concentrated among the top 20 percent of workers. Below the 80th percentile, real wages fell by about 3 percent at the median. It is only in the most recent data (since the beginning of 2015) where there is any sign of real wage growth, at roughly a 3 percent annual rate. If this is sustained, and especially if it accelerates in the coming months, then it might indicate that the labor market has finally begun to tighten. But a few months of data are too little to support this conclusion, particularly when real wage growth has been boosted by low inflation attributable to declines in energy prices. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

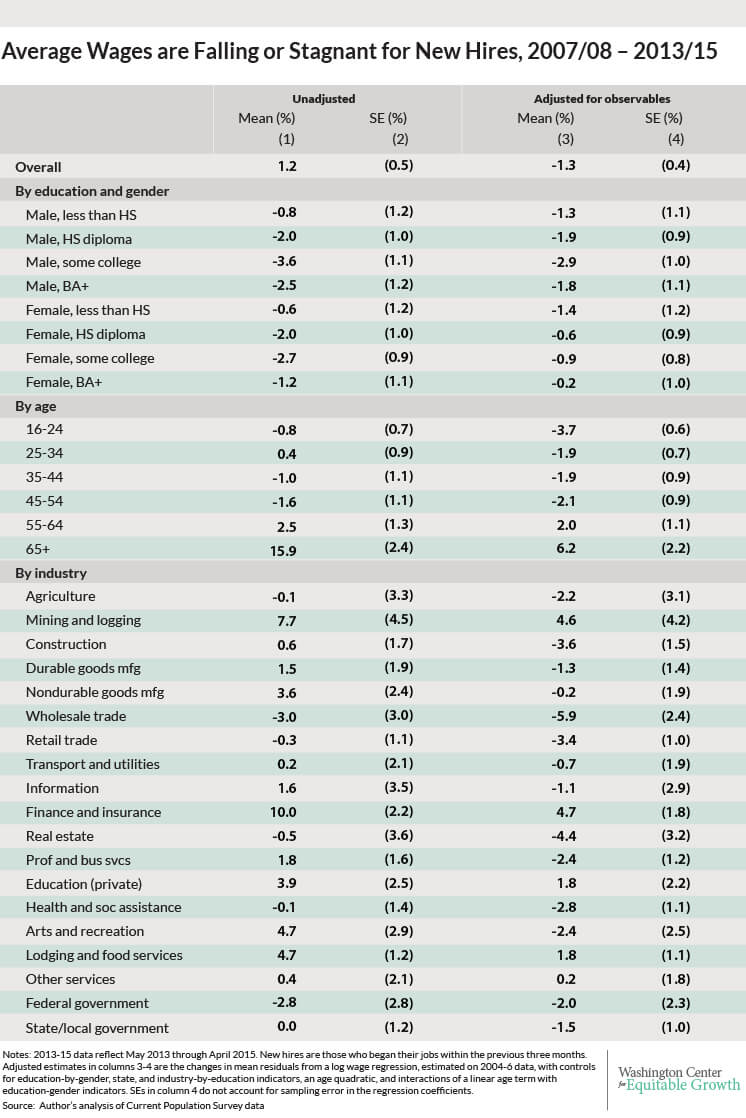

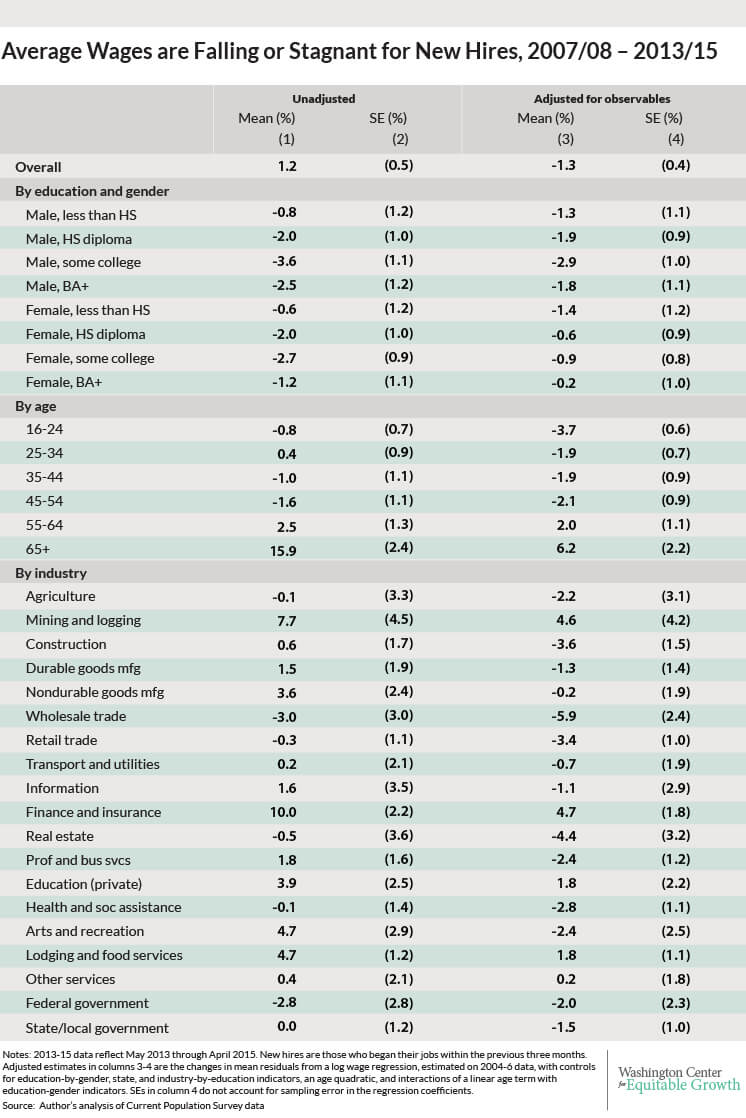

Over the longer period, there is no sign of meaningfully larger wage increases in sectors with rising job openings, as would be expected if these sectors faced persistent labor shortages. Across industries, only the mining and finance sectors appear to have posted meaningful wage increases, and even these have averaged less than 1 percent per year real wage growth. Once again, the patterns in the data are fully consistent with continued demand weakness, and not at all consistent with growing shortages of workers in growing sectors. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

Policy implications

In the years since the Great Recession, the unemployment rate has gradually crept downward while other indicators of the health of the labor market have been stagnant. Lackluster wage growth and high unemployment rates among lower-skilled workers appear to be attributable to a continued shortage of demand in the U.S. economy, combined with greater sensitivity to cyclical conditions of workers on the bottom-rungs of the job ladder. That means the high nonemployment rate among lower-skilled workers is not the “new normal” but rather could be substantially resolved by more robust economic growth and better fiscal and monetary demand-management policies.

Further, my research suggests that increased aggregate demand for workers, at the current level, will not create inflation. At best, we are only in the past few months seeing meaningful tightness. More likely, this is an artifact of declining oil prices, which means the current labor market still has substantial slack. Under the latter interpretation, additional labor demand would improve employment outcomes, with particular benefits for low-skilled workers and other disadvantaged groups who suffer disproportionately from cyclical downturns.

My results also counsel against many of the recommendations made by proponents of the view that the economy has settled into a “new normal.” In particular, there are two ill-advised responses to current conditions in the labor market predicated on a misdiagnosis of the economy as having escaped the cyclical downturn. First, tax cuts or reductions in unemployment insurance or means-tested government transfer programs aimed at increasing labor supply will do more to reduce wages than to increase employment.

Second, education and training programs aimed at increasing the skill of low-wage workers are unlikely to do much to help the labor market when there are demand shortages at every rung of the job ladder. So education and training programs are unlikely to help in the short term. That said, these programs alongside increased income support for low earners still make sense as a response to long-term trends—even if they cannot be expected to contribute meaningfully in the short run.

Taking ill-advised policy steps, such as failing to implement needed fiscal and monetary policies to boost demand for labor, or, worse, implementing policies aimed at tamping down an overheating economy, could extend periods of underemployment, damaging workers’ productivity for many years to come. Every month that the economy continues to underperform is making us poorer for decades into the future. Over-cautious policy could cause substantial damage. It is also crucial to put policies in place now to prepare for the next downturn, to avoid such a sustained, weak recovery.

Conclusion

Claims that the economy is nearing its growth potential, and that ongoing low employment rates are the unavoidable consequence of structural changes in the labor market, are at odds with the evidence. Neither comparisons across industries or education groups, nor analyses of wage growth offer any evidence of tight labor markets pushing up against their limits. Unemployment rates remain higher than in 2007 for all ages, education levels, genders, and industries. Sectors that have been more cyclically sensitive in the past saw larger increases in unemployment in the Great Recession, but there is remarkably little difference beyond this observation in the current data. And wages have continued to stagnate for the vast majority of workers, at least until the very most recent data. All of these patterns are consistent with an ongoing shortfall in aggregate labor demand, and less so with a gradual adjustment to technological or demand-driven shocks that created demand for new types of skills that cannot be satisfied by the current workforce.

—Jesse Rothstein is an associate professor of public policy and economics and the director of the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment at the University of California, Berkeley.

View full pdf here.