…The constraints on fiscal policy are determined by two factors: 1) can you print your own money, and 2) is unemployment already so low that fiscal stimulus is inflationary…. One of the things I dislike about the unthinking obsession with “expectations” in today’s monetary policy discourse is the suggestion that “inflation expectations” can suddenly–out of nowhere–go haywire. This a bit like the idea of bond panic. One day–for some unknown reason–the bond market is going to think that the government won’t raise future taxes, and panic…. But if the central bank can do QE, there cannot be sustained bond panic in the absence of a genuine inflation problem. Why? Because, as the BoJ is showing, faced with no inflation risk, the central bank can buy all the bonds.

All that matters then is what causes a sustained rise in inflation. The idea that the population wakes up one day and decides that because the national debt has gone through the Reinhart and Rogoff limit, or because a check from the Fed has arrived in the post, there is going to be a wild outbreak of inflation, is unconvincing…

Month: April 2015

Must-Read: Richard Mayhew: A Real Problem with the ACA

Weekend reading

This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles we think anyone interested in equitable growth should be reading. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week we can put them in context.

Links

Jordan Weissmann argues the top marginal tax rate should be much higher. [slate]

Ben Bernanke, who knows a thing or two about the topic, discusses the future of monetary policy. [brookings]

Matthew Weinzierl writes about fairness and the reasons for the income tax. [the conversation]

Simon Rabinovitch doesn’t think there’s a bubble in the Chinese stock market. At least not yet. [free exchange]

Josh Zumbrun digs into an IMF study about what caused the decline in oil prices: supply or demand? [wsj]

Friday figure

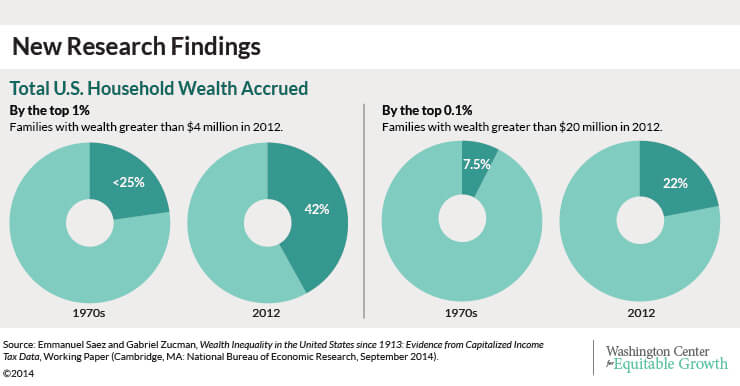

Figure from “Exploding wealth inequality in the United States,” by Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman

Breaking down the decline in the U.S. labor share of income

Understanding why the share of income going to labor is on the decline—a phenomenon stretching back several decades—is an increasingly popular area of economic research. There is some debate as to whether that labor share has declined at all, but in so much as there is agreement about the decline, the particular reason for it is very much debated. A new paper enters a different hypothesis into the debate by looking at how the labor share has changed within two large and different sectors of the U.S. economy, and how changes in technology may be the root cause of the shift.

The paper, by Francisco Alvarez-Cuadrado, Ngo Van Long, and Markus Poschke, all of McGill University, focuses on how differences between the manufacturing and service sectors might be responsible for the decline in the labor share in United States from 1960 to 2005. The U.S. economy, of course, underwent several major structural changes over this period of time amid the decline of labor’s share of income—one of the larger changes being the shift of employment from the manufacturing sector to the services sector. But why did that shift that happen?

The simple answer might be that economic activity shifted toward the service sector because this sector features a lower share of income going to labor, which would result in the aggregate labor share declining. But the authors find that the decline is more due to changes within sectorial labor shares rather than changes between the two sectors. In fact, the manufacturing sector started with a higher share of income going to labor in the 1960s, but the subsequent decline was much larger than the decline in the share of income going to labor in the service sector. So what accounts for the declining labor share if the cause is happening within the two sectors?

According to Alvarez-Cuadrado, Van Long, and Poschke the main factor is a difference in productivity between the two sectors. What they find is the importance of productivity growth depends on what specific kind of growth it is. The key factor, according to this analysis, is that the kind of productivity that the three economists call “labor-augmenting,”or the kind of productivity that does more to enhance the role of labor more than capital.

What the paper shows is that labor-augmenting productivity growth has been higher in the manufacturing sector than in the service sector. Workers with more education or skills are an example of labor-augmenting technological change. At the same time, the three economists find that the manufacturing sector more readily switches between the use of labor and capital than the service sector.

In economics speak, this phenomenon is explained by the elasticity of substitution, which is higher in manufacturing than in services industries, though both are lower than 1. This is particularly interesting given that any elasticity lower than 1 usually isn’t in line with a declining labor share.

What’s even more interesting about this new hypothesis is that technological growth is at the heart of the declining labor share of income. But the specifics show that it’s not the popular “robots” story that is often mentioned in these debates, where capital is displacing labor. Rather, in this new paper by Alvarez-Cuadrado, Van Long and Poschke, capital and labor are complements to each other, not substitutes. Their findings indicate that, technological growth has played a role in the declining share of income going to labor, but not in the way most would expect.

Things to Read on the Afternoon of April 16, 2015

Must- and Should-Reads:

- Must-Read: : Hottest Tax Idea in Washington Actually Terrible

- Must-Read: : The Mistakes Made by Most Development Reformers

- Must-Must-Read: : The Fed Can Be Patient About Raising Interest Rates

- : Europe’s Poisoned Chalice of Growth

- Must-Read: : The New Liberal Consensus Is a Force to Be Reckoned With

- Must-Read: : Research Summary

- : The Zombie Statistic [that Health Care Is Responsible for Just 10% of Overall Health] Revisited

- Must-Read: : Fixed Mindsets

Must-Read: Noah Smith: Fixed Mindsets

…She’s also a hedgehog. Meaning, of course, that she applies her One Big Idea to everything and anything, and tends to exaggerate its power and the evidence in favor of it. That’s OK. Most promoters of big good ideas are hedgehogs…. I think that as a society we’ve gotten good at recognizing hedgehogs and mentally correcting for the hedgehogginess…. Dweck makes it clear many times that natural ability does, in fact, matter. She states that among people of similar natural ability, having a growth mindset makes a big difference. What she is saying is that the marginal effect of the growth mindset on performance is large for most people, even though natural ability matters a lot in the average…

Must-Read: Marshall Steinbaum: Hottest Tax Idea in Washington Actually Terrible

…instead of taxing wealth or income, the government should encourage people to save by taxing only their spending… Rubio… Lee… Cardin…. Too bad they’re all wrong…. The theoretical arguments in favor of consumption taxes are typically based on the injustice of penalizing thrift by the poor. But those are just fables: Saving is overwhelmingly a pastime of the rich…. [It] might sound great in theory, but one that would be revenue and distributionally neutral would create tremendous smuggling opportunities and thus be impossible to enforce…

The path to more U.S. exports?

For most of its 80-year existence, the U.S. Export-Import Bank was a government program decidedly out of the spotlight. But over the past several years the bank has been front and center in debates about the role of the federal government in the U.S. economy. Proponents of the bank argue that the credit it provides is an important service that the free market won’t supply on its own. Opponents argue that the bank just acts as a subsidy for economic activity that would happen anyway in the free market. But in thinking about the program, it might be worthwhile to step back and think about broader macroeconomic conditions given the bank’s potential expiration at the end of June.

The bank, as you can guess from its name, is focused on financing U.S. business activity in international markets. According to the agency’s website, the bank’s mission is to help businesses “turn export opportunities into sales” and “get what they need to sell abroad and be competitive in international markets.” In other words, the bank is all about increasing U.S. exports.

But for anyone who’s taken an economics course on international trade knows, the level of exports really isn’t driven by credit financing. As Veronique de Rugy at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center points out, the bank only supports about 2 percent of all U.S. exports. Rather, much larger macroeconomic factors such as exchange rates and national savings play a decidedly bigger role. So what does determine the trade balance between two countries?

The first country, say China, consumes less than it produces, which means the country has net savings overall. The second country, say the United States, would like to consume more than it produces and in particular wants to buy goods or services from the first country. The result is that the United States ends up borrowing money from China to buy these goods. That’s one reason why China is running a trade surplus while United States is running a trade deficit. After a while, the United States will have to pay back China so it’ll reduce consumption, save more, and the roles will be reversed.

Of course, this process can be interrupted if the exchange rate is altered in some way. Say one of the countries has a currency, such as the U.S. dollar, that a lot of people want to hold to facilitate financial transactions. China, meanwhile, generally sets the exchange rate for its currency to make its exports more competitive in the international market. That means the United States will end up receiving a lot of savings from the rest of the world, including from China, allowing it to consume more than it otherwise would be able to purchase. And the currency will be stronger than it would have been otherwise. The result: a trade deficit with imports exceeding exports.

Whether or not exporters get financing from the U.S. Export-Import Bank, its existence would probably only have a marginal effect on net exports.

Must-Read: Dani Rodrik: The Mistakes Made by Most Development Reformers

…And you realize that they don’t change overnight. Are you better off promoting the set of policies that presume that rule of law and contract enforcement will take care of themselves, or are you better off recommending a strategy that optimizes against the background of a weak rule of law?… I say… you do much better when you do the second. The best example is China. Its growth experience is full of these second-best strategies, which take into account that they have, in many areas, weak institutions and a weak judicial system, and therefore they couldn’t move directly to the kinds of property rights we have in Europe and the United States. And yet they’ve managed to provide incentives and generate export-orientation in ways that are very different from how we would have said they ought to have done it… The same can be said of Vietnam, say, or farther afield, a country like Mauritius.

Today’s Must-Must-Read: Alan Blinder: The Fed Can Be Patient About Raising Interest Rates

…“further improvement in the labor market” (even though the unemployment rate is now back to spring 2008 levels), and convincing evidence that inflation (which has been running below target) is heading back to 2%. Waiting for both may require a lot of—well—patience…. The so-called hawks, who have been calling for rate hikes since 2009, have constantly warned of high inflation lurking just down the road. It must be a long road. The Fed’s favorite measure of core inflation (which omits food and energy prices) has been stuck in a narrow range between 1.3% and 1.7% since mid-2012. Headline inflation, which includes food and energy prices, is roughly zero. If the rationale for interest-rate hikes is heading off inflation, this performance practically cries out for patience…. A tight labor market could push up wages faster. Hawks look at today’s unemployment rate, which is 5.5% and falling, and see a labor market that is already tight and getting tighter. Ms. Yellen and the FOMC majority disagree. They patiently await “further improvement in the labor market”….

The impatience crowd once worried loudly and frequently about a different set of problems. Specifically, that near-zero interest rates and/or quantitative easing were allegedly causing financial-market “distortions” and “bubbles.”… The federal-funds rate has been near zero for over six years now, and the Fed’s balance sheet is roughly five times as large as when Lehman Brothers failed. Yet none of the hypothesized financial hazards have surfaced. So you don’t hear the scare stories much anymore. Here, too, the evidence suggests that patience is the right policy. To be sure, the Federal Reserve will not maintain near-zero interest rates and a $4.5 trillion balance sheet forever. Monetary policy will eventually begin to normalize. But not in June, and maybe not in September. Timing, they say, is everything. This is a time for patience.