…but Vox’s Dylan Matthews brings something news to the table, pointing to the contemporary Democrats’ default anti-poverty policy: get people into a job, any job. Translated that means work supports for jobs with very low pay and scant prospects for upward mobility. The genesis of this policy was the so-called Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996, also known as “welfare reform.”… From 1996 to 2000, most of the evidence on TANF, with one important exception, showed up positive. Poverty decreased, employment and wages increased. The problem for evaluation is that this same period happened to be one of the best in U.S. history, in terms of labor market advance. In addition, the minimum wage (in 1996 and 1997) and the Earned Income Tax Credit (in 1993) increased. This makes it hard to isolate any beneficial effects of TANF. Unfortunately, the positive signs for those in the bottom income quintile (20%) of the population have crumbled since 2000. Truth is, they weren’t that positive to begin with. The impact on work in “leavers” studies (where TANF recipients were tracked after graduating from the program) tended to show work effects in the high teens. Think about that for a second. You’re working, say, one week a month. You increase work (assuming you have the option) by the top of the range, 20%. Instead of working five days a month, you work six days. Twelve extra days a year. Nor does work necessarily mean higher income, since increased earnings offset benefits, and work expenses reduce net income. The other ominous, early sign was income decline for the poorest single mothers’ families, documented by the saintly Wendell Primus and colleagues. (Primus actually resigned from his post with the Clinton Administration after the welfare was signed. How often do you see that.)…

At the time I hoped that the reform might cast a different light on welfare recipients. Instead of being bums, they would be workers. But enrollment in TANF has dropped off the table. Meanwhile, Barack Obama is slurred as “the Food Stamp president.” So the meanness has not dissipated, it has just been redirected…. All this is a lengthy prelude to Matthews’ post. His remedy for a future of lousy jobs is the UBI…. You’re not as much at the mercy of employers…. The chief benefit of the ‘exit’ option is the implied upward pressure on wages. So far, so good. But Matthews’ thrust is actually more radical than that. He is throwing shade on the moral obligation and axiomatic economic imperative of work itself, in particular employed work…. Let’s desacralize work. Dignity of work, my fanny. Work that is truly voluntary would be nice. Work that is compelled as an alternative to destitution does not comport with any reasonable concept of dignity. It’s like the dignity of kicking back to Tony Soprano…

Month: April 2015

Must-Read: Pro-Growth Liberal: Jeffrey Sachs’ Feeble Defense of David Cameron

Finally, there is output growth. In the UK, real (inflation-adjusted) GDP fell by 3.8% from the fourth quarter of 2007 to the second quarter of 2010. It then rose by 8.1% from that point until the fourth quarter of 2014. In the US, real GDP fell by 1.6% from the fourth quarter of 2007 to the second quarter of 2010, and then rose by 10.5% from then until the fourth quarter of 2014. Thus, both countries have experienced moderately high and broadly similar growth rates since May 2010, when Cameron’s government took power.

I have no idea what Paul Krugman did to tick off Jeffrey Sachs so I’ll let him speak for himself. But let’s note the fact that the real GDP in the US was a mere 8.7% higher in 2014QIV than it was in 2007QIV. That is by any measure a terrible economic performance. We should also note that real GDP in the UK has increased only 3.7% over the same period. For anyone to suggest that such a dismal economic record justifies fiscal austerity leaves me wondering where this person learned their macroeconomics.

From my perspective, the remarkable–and remarkably stupid–thing we see here is Jeffrey Sachs’s belief claim that U.S. economic performance since the second quarter of 2010 has been in any sense praiseworthy, and that a government that accomplished that is worth voting for.

It hasn’t.

And the reason that it hasn’t has been (a) extraordinary state- coupled with moderate federal-level fiscal austerity, (b) the failure of the Obama administration to use its housing-finance regulatory powers as tools of macroeconomic management, and (c) the unwillingness and perhaps inability of the Federal Reserve to take up the slack.

In the United Kingdom, the Prime Minister who possesses a majority of the House of Commons is the government: Cameron rules fiscal policy, regulatory policy, and monetary policy. Cameron bears responsibility. In the United States, since the second quarter of 2010 Obama has had no power to pass additional fiscal stimulus and no power to reshape the FOMC. Only housing regulatory policy was under his control. Obama gets to claim nearly-full responsibility for the relatively good things. But Obama has to share only a portion of the blame for the bad things.

Today’s Must-Must Read: Gavyn Davies: Who Is Right About the Equilibrium Interest Rate?

…This justifies a large part of the rate increase shown in the dots chart, a view also explicitly stated by Ms Yellen in her speech on policy normalisation. Mr Summers agrees that the Fed will be forced to deliver the equilibrium rate most of the time, but argues that it cannot do so at the moment because of the zero lower bound…. Summers implies that the equilibrium real rate is not only extremely low… [but] may stay there for many years, thus failing to validate the rise in the equilibrium rate implied by the Bernanke/Yellen view. One interpretation of the market’s pricing of forward short rates is therefore that investors lean on the side of Mr Summers…. The resulting abnormally low real bond yields are obviously a critical under-pinning for buoyant asset prices…. If the FOMC were to make it crystal clear that investors are just downright wrong about the forward path for interest rates, the resulting correction in both bond and equity markets could be severe….

The FOMC… are certainly willing to publish the dots, and to spell out their views on the most likely path for the equilibrium real rate. But they are far from ready to risk a major disruption in the markets by telling investors explicitly that they have misjudged the hawkishness of the Fed. Why is this? Presumably it is because the Yellen camp concedes that there is great uncertainty about the equilibrium real rate…. The Bernanke/Yellen belief that the equilibrium rate will rise in the next 3 years as headwinds diminish is at best conjectural….

What would cause Ms Yellen to act more decisively by ‘shocking’ the market’s path for forward short rates? The equilibrium rate is not directly observable, and is very hard even to estimate within a narrow range. This invites caution. The only reliable signal that the equilibrium rate is rising would be upward pressure on inflation. The so-called ‘whites of their eyes’ policy stance, supported by Mr Summers and several members of the FOMC, would therefore wait until there is clear evidence of rising inflation before becoming confident that the equilibrium rate is rising. Fortunately for global asset prices, Ms Yellen is not yet willing to oppose that point of view with any real conviction.

Determining the optimal U.S. tax rate for higher earners

There are two constants in life: death and arguments about the optimal top marginal tax rate. The proper level of income taxation in the United States has been a hotly contested topic since the creation of the first federal income tax more than a century ago. The debate over the optimal tax rate has only intensified in recent years, as income and wealth inequality in the United States increases while taxes on the rich decline. Policymakers need an empirical answer to the question of the optimal level of taxation on top incomes.

How exactly do economists calculate an optimal level? Until very recently, economic research sought to determine the optimal rate by using just one concept—the highest tax rate that would maximize the amount of revenue collected, bearing in mind the disincentive to work created by taxation. Yet the most cutting-edge evidence tells us that our current estimates of the optimal tax rate are inaccurate because they’re missing important additional pieces of information about the behavioral response to taxes.

View full PDF here alongside all endnotes

So what is the optimal tax rate for top incomes? In order to determine that rate, policymakers should instead consider the following three ways that top earners might respond to tax changes:

- by varying the supply of their own labor (working less)

- by shifting between different types of income (wages and capital) to avoid taxes

- by bargaining for different compensation levels from their employers

In this brief, we examine these three possible responses to higher taxes among the wealthy—responses that economists call elasticities—as posited by economists Thomas Piketty of the Paris School of Economics, Emmanuel Saez at the University of California-Berkeley, and Stefanie Stantcheva of Harvard University. Cutting to the chase, the three authors find that the optimal rate of taxation is much higher when we consider the responses quantified by three different elasticities as compared to one elasticity.

The analysis by Piketty, Saez, and Stantcheva finds that the optimal top tax rate is 83 percent. In contrast, the optimal rate using only one elasticity is 57 percent, which in turn compares to the current higher marginal tax in the United States of 39.6 percent. While 83 percent seems like a very high number, the underlying analysis of the paper is persuasive. Yet, the real take-away is the way the three authors calculate the much higher tax rate, and the importance of top earners bargaining for their compensation in calculating the optimal rate. U.S. policymakers need to understand the more complex responses of high earners to different tax rates. This new understanding is important given the country’s rising economic inequality and the relationship this rising inequality has to economic growth.

What is an elasticity?

Economists often seek to examine how responsive one economic variable will be to a change in another: What is known as an elasticity. Often they’ll explore the elasticity of Variable A to Variable B, such as the elasticity of employment to changes in the minimum wage or the elasticity of work hours to increases in the marginal tax rate. The resulting calculation of that elasticity would tell you how responsive the one variable is to changes in another. The larger the magnitude of the number, the larger the change.

In the case of the employment and the minimum wage, think of an elasticity of -0.1. This would mean a 10 percent increase in the minimum wage would result in a 1 percent decline in the level of employment. Or consider the elasticity of work hours to increases in the marginal tax rate, which economists calculate at -0.2—meaning a 10 percent increase in the marginal tax rate would result in a 2 percent decline in hours worked.

Obviously, many variables are at play in the complex U.S. economy. This is why factoring in other elasticities is important for economists to explore and for policymakers to understand.

A new approach to the problem

In their paper “Optimal Taxation of Top Labor Incomes: A Tale of Three Elasticities,” economists Piketty, Saez, and Stantcheva overturn conventional wisdom on optimal taxation by introducing empirical tests of three key ways that taxes can affect the behavior of top earners. The authors argue that the optimal tax rate for top earners isn’t the result of just one kind of response to taxation, but rather three different kind of behavioral responses, or three elasticities.

When the authors calculate the optimal tax rate using only the criteria that the rate not reduce the amount of time top earners spend working, they find that the optimal top tax rate would be 57 percent. But the authors argue that using just one elasticity misses out on too much that’s going on with the behavior of top earners when tax rates are changed. Instead, we should consider three elasticities.

Elasticity 1: Labor supply response

The labor supply of top earners is economic parlance for the amount of time wealthy individuals will put into work instead of leisure. To find the elasticity of their working hours to the tax rate they pay, the authors first calculate the “supply side” elasticity, which measures the sensitivity of the labor supply of top earners to changes in the top tax rate. As the tax rate increases, individuals start to re-evaluate the trade-off between working and earning more money and not working and enjoying leisure time. If top earners were to stop working then the reduction in the labor supply would not only reduce the amount of taxes collected but, more importantly, could be harmful to economic growth.

That’s why policymakers need to know how responsive to taxation top earners are when it comes to their willingness to work. If they are very responsive, then the optimal tax rate could be lower, all other things being equal. If they are less responsive, the rate could be higher.

The authors calculate this first elasticity by looking at how both the share of income going to top earners in the United States, and U.S. economic output (measured by gross domestic product per person) changed as the top tax rate changed. They find that as the top tax rate went down between 1960 and the end of 2012 the top 1 percent of earners were able to keep more of their income but the growth of GDP per capita didn’t increase. That means this first elasticity is pretty low, at most 0.2.

In short, top earners do not substantially vary their labor supply in response to tax rates.

Elasticity 2: Tax avoidance

Another way that top earners can respond to taxation is to change the kind of income they receive so that they can avoid a higher tax rate. If the tax rate on labor income increases then top earners might shift their income toward capital income that is taxed differently. A chief executive officer at a big corporation, for example, might get his compensation shifted from purely salary to include stock options, which when exercised are treated as capital income. This doesn’t mean the top earners are changing their behavior. Rather they are trying to shelter their money from taxation.

A higher elasticity, or responsiveness, means that an increase in the tax rate would make the earner very likely to change the kind of income they earn. A low elasticity means that an earner would not change her source of income based on changes in the tax rate. In a situation where this elasticity is high, top earners will simply shift all their income away from labor and toward capital—so a high tax on the labor income of top earners would yield little revenue.

To calculate this elasticity, the authors compare the trends in the share of labor income going to the top 1 percent to the trends in the share of income that includes capital gains. What they find is that the trends of the two data series are nearly identical. In fact, Piketty, Saez, and Stantcheva say their estimate for the second elasticity is 0. Top earners in the United States do not tend to shift their income sources in response to changes in the tax rates.

Elasticity 3: Executive compensation bargaining

Many top earners are corporate executives. According to one estimate, 41 percent of the top 0.1 percent of income earners are executives, managers, or supervisors. A growing body of research demonstrates that corporate CEOs and other members of the corporate “C suite” (chief financial officers, chief information officers, chief operating officers, and the like) are not responsible for all the gains in the company’s economic performance for which they are compensated. In other words, a substantial share of top corporate executives’ earnings are comprised of funds from the firm that might otherwise go to other workers, investments in the firm, or to shareholders.

When tax rates are lower, executives have a stronger incentive to bargain for higher compensation. And since this compensation isn’t necessarily due to higher productivity, the struggle is zero-sum—if executives receive compensation for productivity gains they aren’t responsible for then funds that would go toward other ends get diverted. Piketty, Saez, and Stantcheva explain that a higher elasticity means that executives are more likely to bargain for higher pay when tax rates are lower and therefore receive funds that might go elsewhere within the firm.

In order to calculate this elasticity, the economists look at international data to determine the relationship between top tax rates and CEO pay. The data show that in countries with lower tax rates, CEOs have higher average incomes after accounting for the kinds of industries in which their companies compete. Piketty, Saez, and Stantcheva interpret this finding as the sign of a high third elasticity, which they calculate conservatively at 0.3 at the lowest. This would mean a higher tax rate on top earners would reduce what economists call rent-seeking—the taking of undue compensation—within the firm, potentially increasing wages for average workers.

Conclusion: The optimal rate?

The research presented in “Optimal Taxation of Top Labor Incomes: A Tale of Three Elasticities,” by economists Piketty, Saez, and Stantcheva, suggests that the conventional wisdom around optimal taxation rates for top earners is missing some nuance in how top earners respond to taxation. Including the bigger picture would seem to leave substantial room for an increase in rates on top earners. Piketty, Saez, and Stantcheva’s calculate that the optimal top tax rate comes out to 83 percent, once their three elasticities—labor supply, tax avoidance, and bargaining—are combined.

Compare that result to the result of 57 percent when economists only consider the overall elasticity of income to tax rates. This level is also much higher than the current top federal income tax rate of 39.6. This isn’t to say that our current top tax bracket should be raised to 83 percent tomorrow. Rather, this is the optimal rate for those at the very top of the income ladder. The top tax bracket would have to be changed in order to tax only those individuals or households at the very tippy top at this new 83 percent rate.

The results of this research also indicate that the rise in income inequality at the very top of the income spectrum was driven primarily by the decline in tax rates, which allowed top earners to get higher incomes without increasing the pace of economic growth. So the main take-away from latest research is clear: Tax rates in the United States on incomes at the very top could be much higher without affecting output growth and potentially boost wages for average workers.

Intangible assets and the labor share of income

Here are a few trends that have been going on in the United States over the past several decades: The share of income going to labor has declined. Corporate profits as a share of the economy have increased. And net investment (outside of the construction industry) has stagnated. Explaining all three of these facts in one coherent story about what’s happened to the economy since the late 1970s doesn’t necessarily fit with a few well-known hypotheses about the relationship between labor and capital.

First, take the research of Loukas Karabarbounis and Brent Neiman, both of the University of Chicago. In their view, the share of income has declined because capital has become less expensive due to technological progress. Computers have become much cheaper, so companies have responded by buying more computers and displacing workers. In economic models, this would require the elasticity of substitution between capital and labor to be greater than 1. In other words, companies being able to readily switch between capital and labor.

Karabarbounis and Neiman’s hypothesis makes sense when accounting for the decline in the labor share. But if that share were going down because firms were buying more capital equipment such as computers, then investment would be increasing as a share of the economy. But it’s not. We know that the price of investment goods is declining, so it looks like firms are just keeping the savings from the decline in the prices instead of investing more. That would explain the increasing profit share as well.

While the mechanics of how the labor share decreased are different, Research by Thomas Piketty of the Paris School of Economics also depends upon the elasticity of substitution between capital and labor to be greater than 1 to show that the labor share of income is declining, but he posits different reasons for this happening. His mechanism is that the rich increasingly save their income and the resulting deepening in capital results in a declining labor share. In his research with Gabriel Zucman of the London School of Economics, Piketty finds an elasticity greater than 1, but like Karabarbounis and Neiman, this result comes from looking at macroeconomic aggregates.

When the elasticity is estimated at a micro level, however, it looks like the elasticity is lower than 1, meaning that switching capital investments for human labor is not as productive. Ezra Oberfield of Princeton University and Devesh Raval of the Federal Trade Commission looked at how individual firms substitute between labor and capital and built that up to an aggregate elasticity that is less than 1. Yet they also found that the labor share has declined.

What could explain a declining labor share with an elasticity lower than 1? A look at the assets of corporations reveals a potential answer. Economist Robin Hanson at George Mason University reports on data that shows that 5/6ths of market valuation of the S&P 500 companies are now “intangible assets” such as patents and trademarks, intellectual property and, importantly in this case, brand names and business methodologies.

To understand this concept, imagine that you want to replicate a company. Let’s say it’s Facebook. You go out and buy all the assets of the company: servers, real estate, and the firm’s employees. But Facebook’s large amount of “intangible assets” means that if you purchase all these physical assets you’d only have a firm that was less than the original firm. The original Facebook obviously has something intangible that can’t be replicated. For the S&P 500 overall, the replicated firm would only be worth 1/6 of the original firm.

Hanson runs through potential explanations for why these intangibles have increased in importance. They include patents, branding, and monopoly power. His colleague at George Mason University, Tyler Cowen, does warn that part of this increase in intangible assets could be from measurement error, but still it seems that any one of these reasons would mesh with the three theoretical explanations above about why capital investments are low yet the labor share of income is still declining (with an elasticity below 1).

Especially when it comes to monopoly power, increased profits and stagnant investments are the sign of monopolies. In his widely read research on the labor share, Massachusetts Institute of Technology PhD. student Matt Rognlie points to a potential increase in market power among companies.

If market power is a significant reason for the increase in intangibles, then this means economists need to focus on understanding how market power and monopolies work in the modern age. Can we do anything about the natural monopolies that arise from social networks companies? Would we want to? Those and many more questions would have to be dealt with.

Things to Read on the Evening of April 12, 2015

Must- and Should-Reads:

- Afternoon Must-Read: : Job Turnover and Workers’ Wellbeing

- : “I finished Inequality: What Can Be Done? by Tony Atkinson, and think it’s great. If you’re only going to read one book on the subject, this is more useful than Piketty…. His main focus is how firms make these choices and exercise their market power. What constraints do they face? This depends on the state, and on corporate governance, and on finance. All of these offer paths to influencing income distribution…”

- : Draghi’s Doom Loops: More than Just the Euthanasia of the Rentiers

- (2001): A Theory of the Consumption Function, With and Without Liquidity Constraints

Might Like to Be Aware of:

- : “‘Climate change is going to lead to overall much drier conditions toward the end of the 21st century than anything we’ve seen in probably the last 1,000 years,’ said Benjamin Cook…. But despite the drier conditions and the apocalyptic headlines, California is unlikely to become a parched, uninhabitable hellscape, experts say…”

- Morning Must-Read: The American Prospect 25th Anniversary

- Today’s Must-Must-Read: : What Causes Recessions?

Morning Must-Must-Read: Noah Smith: What Causes Recessions?

…believe that recessions are a natural, even healthy process… responses to changes in the rate of technological progress, or to news of future progress, or even bursts of creative destruction. Others… believe that there’s something blocking the market from adjusting to the shocks that buffet it. The market adjusts by the price mechanism…. So if you want to show that the market doesn’t naturally self-regulate, the simplest and easiest way is just to show that prices themselves can’t adjust in response to events. This phenomenon is called ‘sticky prices.’… Greg Mankiw and Lawrence Ball wrote an essay for the National Bureau of Economic Research entitled ‘A Sticky-Price Manifesto.’…

The economic establishment reacted harshly…. ‘Why do I have to read this?’ fumed Robert Lucas, the dean of macroeconomics. ‘This paper contributes nothing.’ He went on to accuse the sticky-pricers of being opposed to science and progress:

But Lucas fumed in vain…. Sticky-price theorists proved that you didn’t need a lot of price stickiness to mess up the smooth working of the economy. Even the tiniest dash of stickiness would turn all kinds of theories on their heads…. Sticky-price models still have their dogged opponents here and there throughout the macroeconomics world. Steve Williamson of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis dismisses sticky prices on his blog, saying that the Great Recession went on too long to have been caused by price stickiness, and that sticky-price models have conquered central banks mainly due to slick marketing…. The moral of the story is that if you just keep pounding away with theory and evidence, even the toughest orthodoxy in a mean, confrontational field like macroeconomics will eventually have to give you some respect.

People should read Robert Lucas’s unhinged discussion of Ball-Mankiw:

Robert E. Lucas, Jr. (1994), “Comments on Ball and Mankiw,” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 41, pp. 153-155….

Why do I have to read this? The paper contributes nothing not even an opinion or belief–on any of the substantive questions of macroeconomics. What fraction of U.S. real output variability in the postwar period can be attributed to monetary instability? Cochrane’s paper addresses this question, as have Barro, Kydland and Prescott, Shapiro and Watson, and many other recent writers. It appears to be a very difficult one. Ball and Mankiw have nothing to offer on this question, beyond saying, trivially, that they believe the answer is a positive number and suggesting, falsely and dishonestly, that others have asserted it is zero. Yet monetary non-neutrality is the intended subject of their paper!

One can speculate about the purposes for which this paper was written–a box in the Economist?–but obviously it is not an attempt to engage other macroeconomic researchers in debate over research strategies. The cost of the ideological approach adopted by Ball and Mankiw is that one loses contact with the progressive, cumulative science aspect of macro-economics. In order to recognize the existence and possibility of research progress, one needs to recognize deficiencies in traditional views, to acknowledge the existence of unresolved questions on which intelligent people can differ. For the ideological traditionalist, this acknowledgement is too risky. Better to deny the possibility of real progress, to treat new ideas as useful only in refuting new heresies, in getting us back where we were before the heretics threatened to spoil everything. There is a tradition that must be defended against heresy, but within that tradition there is no development, only unchanging truth. Research that was in fact directed at difficult questions becomes trivialized, no matter which side it is on. Hume, Friedman, Schwartz, Keynes, Hicks, Modigliani become merely interchangeable spokesmen for a fixed set of ideas.

Why does it matter that Friedman and Schwartz carefully assembled and examined data on U.S. monetary history, if the real effects of changes in money were evident to Hume, who had no systematic data on either money or production? Why does it matter that Hicks and Modigliani showed us how to distill intelligible equation systems out of the confusions of Keynes’s Genera/ Theory? Why does it matter that theorists today are developing new models of pricing? If work like this represents progress, it must be because it contributes to resolving some difficulty or deficiency with earlier theory or evidence or both. If the IS/LM model as passed on to us by Hicks and Modigliani is all we need, why do I need to work through hard papers by Caballero or Caplin and Leahy? If these papers offer nothing more than debating points against heretics, I would rather do something else!…

For Ball and Mankiw there can be no real progress, so real business cycle theory is only a threat: It must be defeated, and then we can go back to where we were “a generation ago” (to quote from the draft given at the conference). The possibility of a synthesis of old and new ideas that might leave us better off cannot be envisioned. A few years ago, one of my sons used the Samuelson-Nordhaus textbook in a college economics course. When I visited him, I looked at the endpaper of the book to see if actual GNP was getting any closer to potential GNP than it had been in the edition I had used many years earlier. But the old chart was gone, and in its place was a kind of genealogy of economic thought, with boxes for Smith and Ricardo at the top, and a complicated picture of boxes connected by lines, descending down to the present day. At the bottom were three boxes: On the left, a box labelled “Communist China”; in the center, and slightly larger than the rest, a box labelled “Mainstream Keynesianism.” The last box, on the right, was labelled “Chicago monetarism.”

Times change. Accordingly, to Ball and Mankiw, Chicago monetarism (or at least Milton Friedman) now shares the middle, mainstream box, and there is a new group for the right-hand box, to be paired with the Chinese communists. But the tradition of argument by innuendo, of caricaturing one’s unnamed opponents, of using them as foils to dramatize one’s own position, continues on. I am sorry to see it perpetuated by Ball and Mankiw, and I hope they will put it behind them and return to the research contributions we know they are capable of making.

Weekend reading

This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles we think anyone interested in equitable growth should be reading. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week we can put them in context.

Links

Noah Smith asks: what causes recessions? He takes a look at “sticky prices.” [bloomberg view]

Ryan Decker writes about public earnings buying private firms. [updated priors]

What’s responsible for wage stagnation? William Galston points to international trade and China. [wsj]

Steve Randy Waldman on the trilemma of liberalism, inequality, and nonpathology. [interfluidity]

David Andolfatto interviews Giuseppe Moscarini on the job ladder and the employment recovery from the Great Recession. [st louis fed]

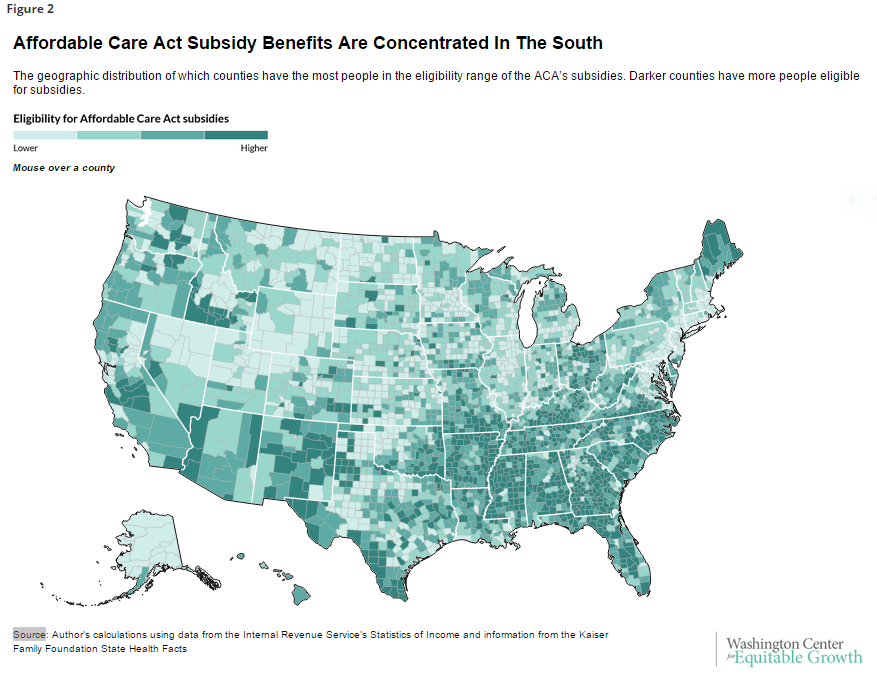

Friday figure

Figure from “Where do the beneficiaries of the Affordable Care Act live?” by Carter C. Price and David Evans.

Morning Must-Read: The American Prospect: 25th Anniversary

The American Prospect: “Join us for a Gala 25th Anniversary Luncheon featuring Senator Elizabeth Warren…

…Wednesday, May 13, 2015 – 11:00am-2:30pm | Hyatt Regency Capitol Hill, Columbia Ballroom | 400 New Jersey Ave NW, Washington, DC 20001. The program will feature keynote Elizabeth Warren—plus a discussion on the role of journalism like ours in progressive politics… celebrating The Prospect’s own work… celebrating and featuring our more than forty past Writing Fellows…. The panel will include some of the brightest stars among the alums of our Writing Fellows program:

- Nick Confessore, New York Times, Fellow ’98-‘99 Follow @nickconfessore

- Matt Yglesias, Vox Media, Fellow, ’03-‘04 Follow @mattyglesias

- Kate Sheppard, Huffington Post, Fellow, ’07-08 Follow @kate_sheppard

- Adam Serwer, BuzzFeed, Fellow ’08-’10 Follow @AdamSerwer

- Nathalie Baptiste, American Prospect current Fellow Follow @nhbaptiste

From its founding in 1990, The American Prospect has been a voice of a practical progressive politics. We are still the same Little Magazine with Big Ideas that the founders intended. The Prospect’s mission for 25 years has been to strengthen the capacity of activists, engaged citizens, and public officials to pursue new policies and strategies for social justice. Through our Writing Fellows program, the Prospect opens a pathway for new, younger, and more diverse voices to join the public debate.

Morning Must-Read: Technology and Jobs: Should Workers Worry?

Global Conference 2015 | Technology and Jobs: Should Workers Worry? » Milken Institute:

The Beverly Hilton | 9876 Wilshire Blvd. | Beverly Hills, CA 90210

Tuesday, April 28, 2015 / 3:45 pm – 4:45 pm

Moderator: Josh Barro, Correspondent, New York TimesSpeakers:

- Brad DeLong, Professor of Economics, U.C. Berkeley

- Jeremy Howard, CEO, Enlitic

- Gerald Huff, Principal Software Engineer, Tesla Motors

- Amy Webb, Digital Media Futurist; Founder, Webbmedia Group

For centuries, people have worried that new technologies will destroy jobs without creating enough new ones, and every time the doomsayers have been proven wrong. But today, with disruptive advances occurring at dizzying speed, some worry that the time may finally have come when more jobs are destroyed by technology than are created. One 2013 report by Oxford University researchers concluded that 47 percent of U.S. jobs are threatened by automation. Should workers be worried, or is the fear overblown? Is technology–from robots to intelligent digital agents–our friend or a threat? If the latter, what do we need to do to ensure employment by the middle class and others? How can we reorganize our business and economic system to avert more economic turmoil?