Who benefits from the booming U.S. stock market?

The U.S. stock market is on a roll. The S&P 500, a broad index tracking companies publicly listed in the United States, experienced 25 percent growth over the past year. The more familiar Dow Jones Industrial Average climbed to historic highs over the same period. But what does this mean for the broader U.S. economy? A rising equity market may be a sign of rising confidence in the economy, but it’s not clear how much tangible benefit will flow to most Americans.

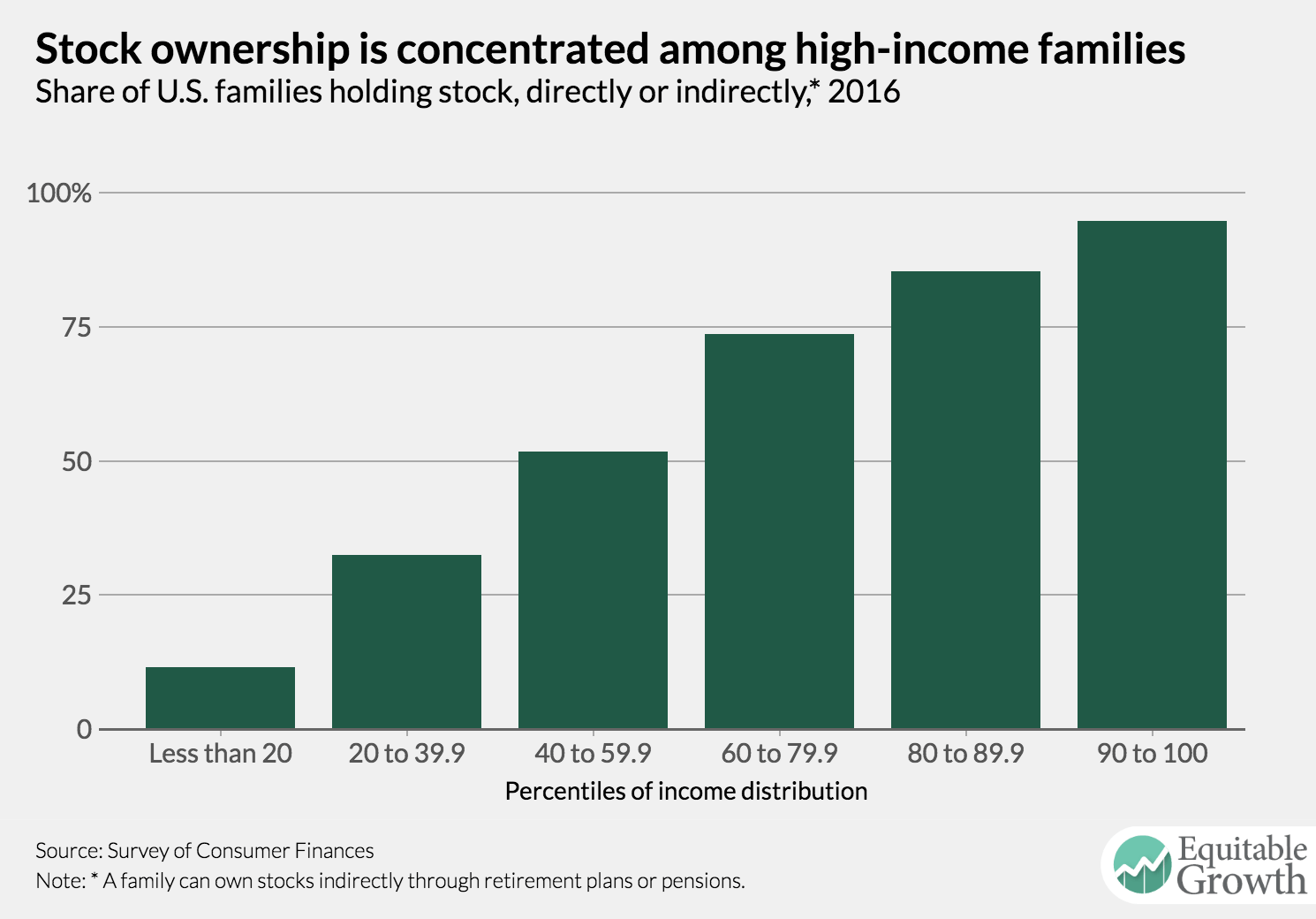

First, the direct benefits to most households will be limited because not that many households own stock. Slightly less than 52 percent of U.S. families hold stock, either directly or indirectly, according to the Survey of Consumer Finances. (A family can own stocks indirectly through retirement plans or pensions.) The distribution of this ownership, however, is quite skewed. The bottom 40 percent of families by income own stock at a much lower rate, with only 11.6 percent of households in the bottom 20 percent owning stock, while only 32.5 percent of the next 20 percent did as of 2016. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Even when lower-income households do own stock, the differences in amount owned is quite large. The median value of stocks owned by the roughly 12 percent of the bottom 20 percent of families was $6,000 in 2016. Compare that to the median value of $363,400 for the 94.7 percent of the top 10 percent of families who own stocks. A rising stock market is going benefit those who own more stocks. In the United States, that’s already-wealthy households.

Higher stock prices, however, also may have an indirect benefit to most U.S. workers. A rising stock market could signal to companies that they should invest more because these firms’ rising financial valuations are above the value of the firm’s capital. This kind of thinking lies behind what’s known as “Tobin’s Q,” the ratio of a firm’s financial value (market capitalization) to the value of its assets (book value). If the ratio is greater than 1-a financial value higher than its book value-then Tobin’s Q suggests that a company should invest more in its operations and its workforce. A rising stock market could lead to more investment, which would also lead to higher wages for workers.

The problem with expecting Tobin’s Q to play out as theorized is that the financial value of U.S. firms has been outpacing the value of their tangible capital for some time now. Research by economists German Gutierrez and Thomas Philippon of New York University details how business investment growth in the United States has become detached from profit growth. So this indirect channel seems unlikely to lead to significantly broader long-term prosperity for most Americans. In fact, there’s evidence in Gutierrez and Philippon’s research to suggest that profits are increasingly leading to share buybacks and dividends, which boost prices for existing shareholders. Some of these payouts may get reinvested in other firms, but if the disconnect between valuation and investment continues, then those reinvested returns won’t do much to boost investment.

Putting aside the usefulness of indices of the U.S. stock market for understanding the overall health of the U.S. economy, these same measures also might be less useful for understanding the health of U.S. business income and values. The number of publicly listed firms in the United States peaked in 1996. Business income is increasingly shifting toward privately held firms such as partnerships and other so-called pass through businesses. Looking at the S&P 500 or the Dow Jones Industrial Average will tell you something about publicly held companies, but that information is less applicable to all companies operating in the U.S. economy than it was in the past.

To be clear, a rising U.S. stock market is certainly better than a falling one. Policymakers should be aware of who benefits from the rising market-those who are already doing so well. But absent reforms to broaden stock ownership and to help reconnect business investment and profit growth, policymakers shouldn’t get overly excited about a booming stock market.