Why do some jobs pay better than others? Think about what workers do.

Overview

Most U.S. labor market data characterize jobs by describing the categories of industry and occupation to which the jobs belong. But to understand why some types of jobs tend to pay well while others do not, even the most detailed versions of these categories are not that helpful. Nothing about the terms “fast food and counter workers” and “bioengineers and biomedical engineers” explains why workers in the former category tend to have low wages while workers in the latter category tend to have high wages.

To understand differences in wages across occupations—why some jobs pay better than others—it helps to consider how the content of jobs differs across occupations. What do people do at work? What skills do they use? What talents or abilities help people perform well? Data from the Occupational Information Network, or O*NET, help researchers measure how occupations differ on these dimensions, among many others.

In particular, O*NET measures the degree of importance and complexity of dozens of skills, abilities, and work activities within hundreds of detailed occupations. To make things concrete:

- Skills are capabilities people develop that help them learn or do their jobs. Examples include critical thinking, active listening, computer programming, and complex problem solving.

- Abilities are more permanent talents that can help people do their jobs. Examples include stamina, memorization, and written expression.

- Work activities are sets of similar actions or tasks performed together across different jobs. Examples include staffing organizational units, performing administrative activities, selling or influencing others, and scheduling work and activities.

For each skill, ability, and work activity, a combination of expert analysts at O*NET and workers surveyed about their jobs assess the importance of each of these more-detailed job characteristics (on a five-point scale) and the degree of complexity involved (on a seven-point scale) in how they figure into each occupation. Correlating these measures with wages can help reveal what is driving pay differences across occupations.

This issue brief will explore these differences in pay across a variety of occupations and how real wages, after factoring in inflation, changed over the course of the past 25 years. While policymaking undoubtedly plays an important role in wage dynamics over time, it is also important to have a clear understanding of the role played by economic fundamentals. Our aim is to begin an examination of how demand for skills, abilities, and work activities changed across and within different occupations, explore how these changes relate to job quality, and lay the groundwork for discerning how the U.S. labor market will shift anew as new technologies such as artificial intelligence become more prevalent in U.S. workplaces.

How do wages relate to job content?

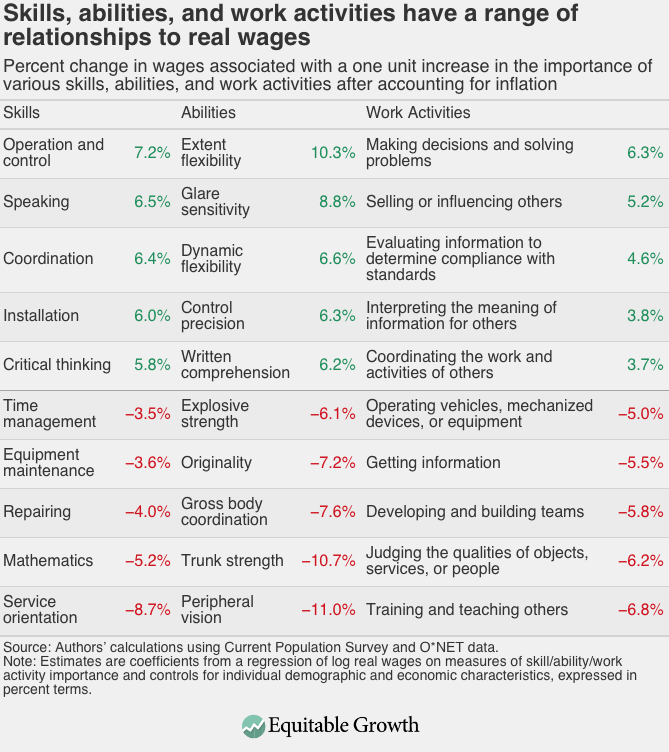

Because the content of jobs in any given pair of occupations will differ on many dimensions at once, we use a regression framework to consider how the importance of each skill, ability, and work activity that O*NET measures relates to wages. Our estimates answer the question, “A one unit increase in the importance of this characteristic is associated with what percent change in average wages, holding all else constant?” We start by using data from 2020 through 2024.

Table 1 below shows the five skills, abilities, and work activities that we estimate to have the strongest positive and negative correlations with wages. Some of these correlations may be surprising. Within skills, for example, consider mathematics, which is negatively correlated with real wages. If you expected mathematics to be positively correlated with wages, why is that? Could it be because mathematics skills help workers complete in-demand, remunerative tasks, such as making decisions and solving problems, which are among the activities most positively associated with wages? Or because mathematics seems similar to other important skills such as critical thinking, which is among the most positively associated with wages?

By comparing occupations on all these dimensions at once, our regression attributes to each one only the relationship with wages directly connected to it, rather than lumping together contributions from sets of connected characteristics. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

Next, we investigate how the relationships between skills, abilities, and work activities have changed over time. Figure 1 below shows how the association between each skill, ability, and work activity and real wages, after accounting for inflation, has changed between 2003–2007 and 2020–2024. (Characteristics are sorted according to their 2020–2024 correlations with wages.) Several characteristics have registered substantial shifts in their wage correlations over this period, including many that are currently among the most positively and negatively correlated with wages.

The physical abilities that appear in Table 1, in particular, have displayed big shifts since 2003–2007. Extent flexibility (the ability to bend, stretch, twist, or reach), glare sensitivity (the ability to see objects in the presence of glare or bright lighting), and dynamic flexibility (the ability to quickly and repeatedly bend, stretch, twist, or reach) have all gone from being minimally or negatively correlated with wages to among the abilities most positively correlated with wages. At the other extreme, trunk strength and explosive strength went from having positive wage correlations to having among the most negative wage correlations. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

This raises interesting questions about what has happened. Differential progress in the development of technologies that assist or replace the performance of work requiring strength and gross body movements versus precision and fine motor control could have changed the relationship between the importance of these abilities for workers and the associated compensation. Looking further into these and a number of other shifts depicted in Figure 1 would be very interesting for researchers to further detail these changing workplace dynamics.

It is also interesting to think about how these relationships might change in the future. Rapidly developing artificial intelligence technologies are very likely to change the content of some jobs in the short term to medium term, and the range of longer-term possibilities is wide. We will address questions related to AI more extensively in a future column.

Did job content matter for post-pandemic wage growth?

Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020—and potentially encouraged by the policy responses to it—the U.S. labor market experienced a period of unusually high job turnover, first driven by layoffs amid pandemic shutdowns and later driven by voluntary quits. Collectively, this period has sometimes been called the Great Resignation or the Great Reshuffle.

One important consequence of this period is that many workers were doing different kinds of work at the end of it than they were at the beginning. At the same time, pandemic conditions led to large shifts in consumption, first away from and then back toward in-person services. Could these shifts have been accompanied by changes in the returns to earnings of different skills, abilities, or work activities?

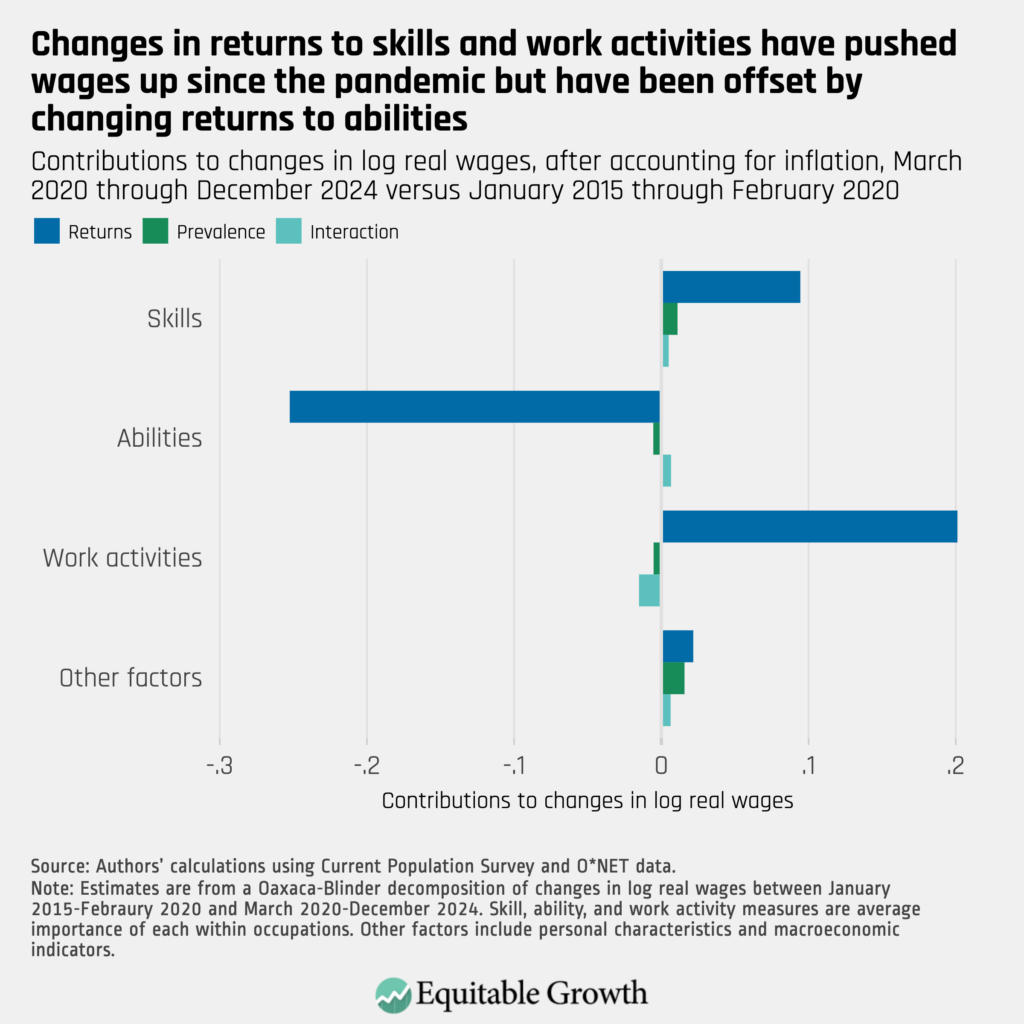

From the beginning of the pandemic through the end of 2024, real wages were about 9 percent higher on average than they were from the beginning of 2015 through February 2020. We use a statistical technique known as the Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition to break down how changes in the prevalence of various skills, abilities, and work activities (their average importance across jobs) and changes in the returns to those same skills, abilities, and work activities (the correlation between their importance and earnings) contributed to that difference. The decomposition also attributes some of the change in wages to the interaction between changes in prevalence and changes in returns.

Figure 2 below shows the results of our decomposition. Collectively, changes in the relative importance of skills, abilities, and work activities in the average job made only minor and partially offsetting contributions to the difference in average real wages between these two periods. The change in the relative importance of skills pushed wages up slightly, while the change in the relative importance of abilities and work activities pushed wages down slightly. Combined, these changes in the importance of the average skill, ability, or work activity pushed wages down slightly. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Change in the returns to these characteristics made more substantial contributions to the change in real wages. Changes in the returns to work activities pushed real wages up by about 21 percent, while changes in the returns to skills pushed real wages up by nearly 8 percent. This was offset, however, by changes in the returns to abilities, which pushed wages down by about 26 percent.

Changes in both the composition of other controls, such as demographic characteristics and macroeconomic indicators, and their returns tended to push real wages up slightly after the pandemic. Overall, changes in returns accounted for a statistically significant 6 percent increase in real wages, with changes in average values of those characteristics across periods and interactions between those two types of changes accounting for the rest.

What else matters for wages?

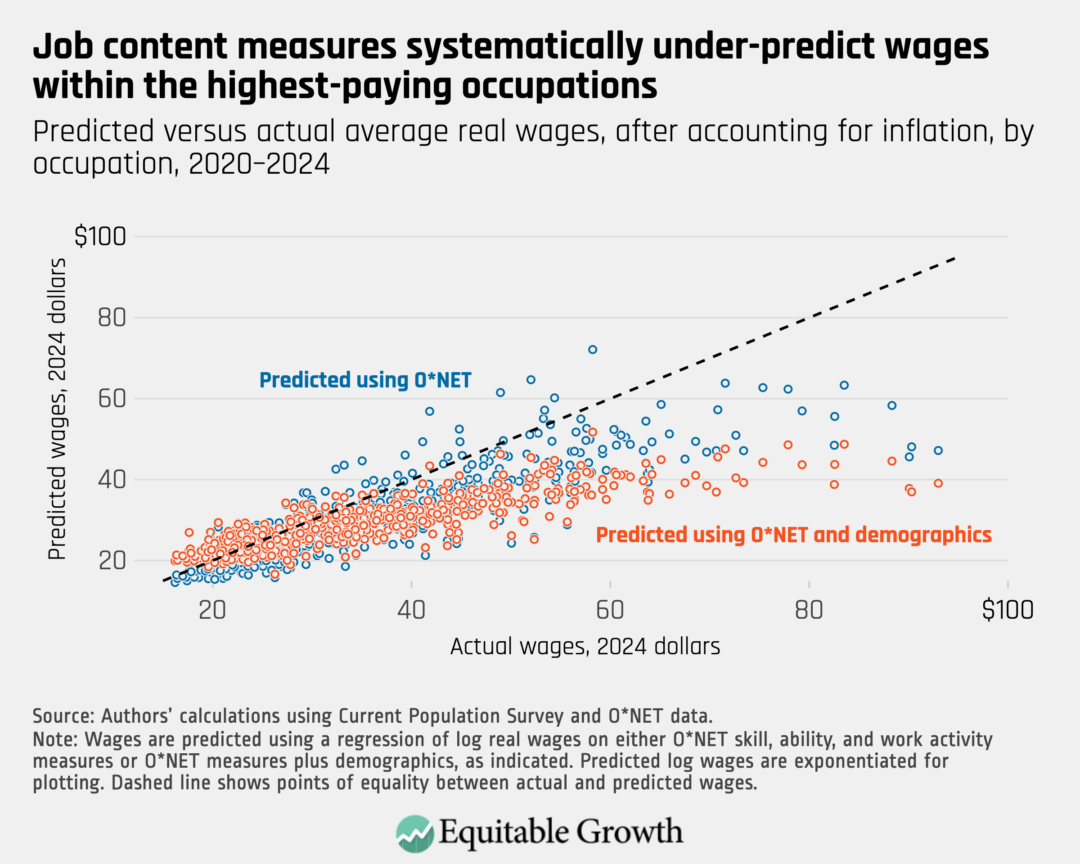

As useful as considering the content of jobs is for understanding why some occupations have high wages and others have low wages, the measures considered here are far from the only things that matter for wages. Differences in job content across occupations explain about 31 percent of variation in wages in a simple individual-level regression of log real wages on skill, ability, and work activity importance from O*NET.

This is a relatively large amount for a few categories of occupational characteristics but still far from most of the variation. Figure 3 shows that estimates from that regression systematically underpredict average wages in the highest-paying occupations. Adding workers’ personal characteristics to this regression does not change this result (and, if anything, exacerbates the issue). (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

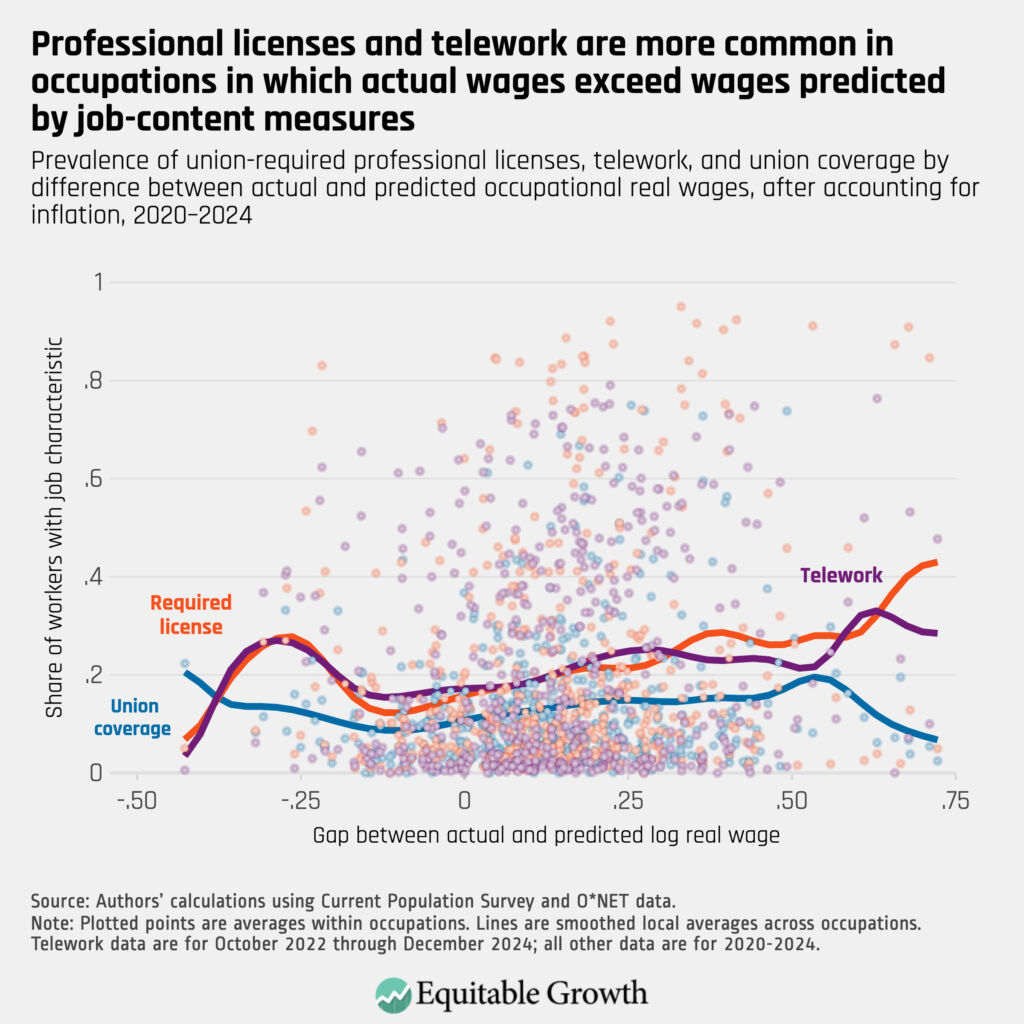

This gap between actual real wages and those wages predicted using measures of job content in high-paying occupations raises an interesting question: Why else are these occupations so high-paying? What else makes these jobs good? As an initial exploration of this question, Figure 4 looks at how a few other job characteristics vary with the gap between actual and O*NET-predicted occupational real wages. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

Barriers to entry could provide one explanation for how jobs that are already expected to be high-paying based on their content end up being even higher-paying than expected. Many high-paying jobs require substantial education, but some also explicitly require professional certifications, such as a medical license for doctors or admission to the bar for lawyers. Figure 4 shows that required licenses or professional certifications are indeed more common in occupations with larger gaps between actual real wage and O*NET’s predicted wages. While this is only suggestive, it illustrates another factor worth considering when thinking about what makes jobs good.

The gap between actual and predicted wages may even understate the degree to which wages in high-paying occupations exceed those predicted by job-content measures. Telework—an amenity that the average worker would be willing to give up a nonnegligible share of their wages to access—is also more common in occupations with larger gaps between actual and predicted wages. This is likely also true of other forms of compensation, such as employer-sponsored health insurance or retirement plans, which are available more often in higher-paying jobs. Union representation, one mechanism by which workers might try to secure higher pay or access to benefits, does not seem to be systematically related to the gap between actual and predicted real wages.

Conclusion

Differences in job content play a meaningful role in explaining why some occupations have high wages and others have low wages. But the relationships between measures of job content and wages are not necessarily stable, as shifts over the past two decades indicate. These shifts can have macroeconomically important implications, a possibility to which to remain attuned, as AI technology continues to develop. As informative as these relationships are, a full accounting of differences in wages across types of jobs should also consider how job content interacts with other forms of compensation, such as fringe benefits and job amenities, as well as how barriers to entry influence wages in certain jobs.