U.S. tax revenue will rise modestly in the next 10 years, no thanks to corporate taxes

The Congressional Budget Office’s latest budget and economic outlook for 2017 and beyond estimates that overall federal tax revenue will be on the rise over the next decade if current tax laws remain unchanged. Yet the CBO also anticipates that this growth in tax revenue will be tempered by decreases in receipts from specific sources, including the payroll tax and the corporate income tax.

The report forecasts that revenues will grow modestly relative to U.S. gross domestic product between this fiscal year ending September 30th and 2027. A majority of this growth is expected to be driven by an increase in revenues from individual income taxes, which will rise from 8.6 percent of GDP in 2017 to 9.7 percent of GDP by 2027 thanks to “bracket creep,” an aging population that will begin accessing more and more retirement income, and fast-growing earnings for those at the top of the income ladder. Revenues from payroll taxes and other taxes, which includes the excise, estate, and gift taxes, will see small declines from 6.0 percent and 1.5 percent of GDP to 5.9 percent and 1.2 percent of GDP in 2027, respectively.

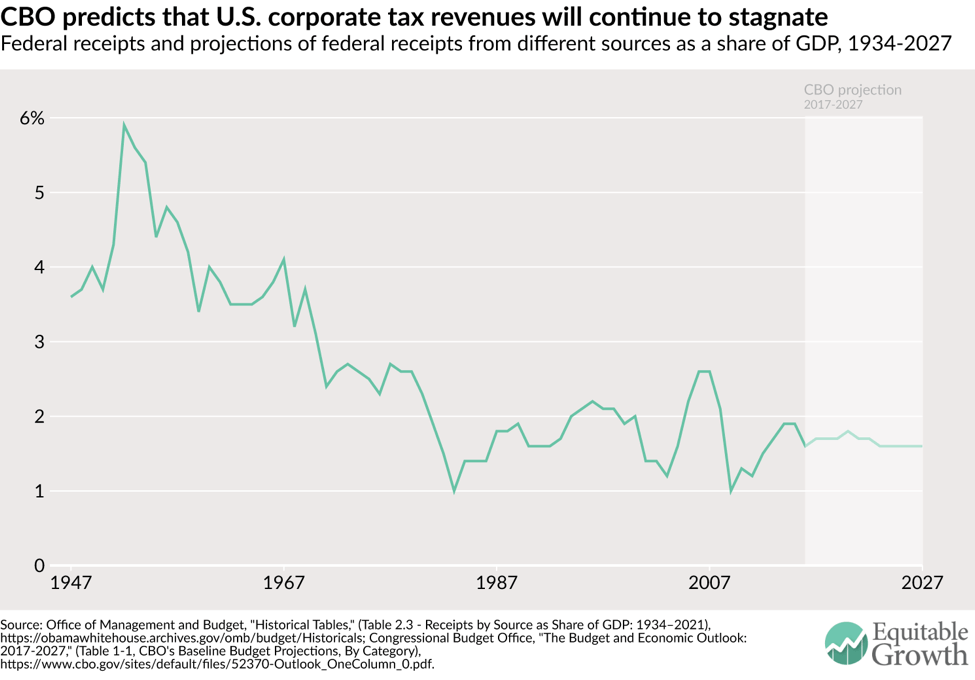

The trends in corporate tax revenues, however, are an interesting case. In fiscal year 2017, receipts from corporate income tax are expected to amount to 1.7 percent of GDP. By 2027, the Congressional Budget Office anticipates that these revenues will fall by 0.1 percentage point to 1.6 percent of GDP. This small predicted drop is actually part of a longer trend: In the United States, corporate tax revenues as a share of the economy have been relatively stagnant since the mid-1980s. (See Figure 1).

Figure 1

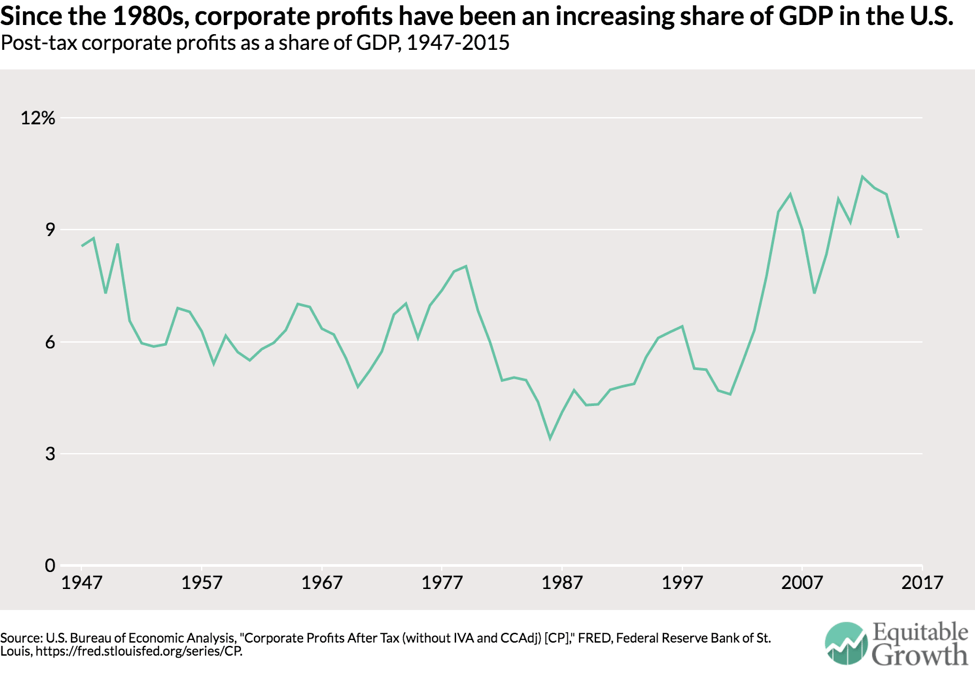

Over this same period, though, corporate profits have grown sharply. Between 1985 and 2015, corporate profits as a share of GDP rose by 4.4 percentage points. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Rising corporate profits in a time when corporate tax revenues remain relatively stable suggests that effective corporate tax rates are declining. In fact, in their models, the Congressional Budget Office assumes that businesses and investors will continue to find new ways to reduce their tax rates, which is part of the reason that corporate receipts face a small decrease in the next decade. The continued erosion of corporate tax revenues will have long-term effects on total federal revenues and could even contribute to a further rise in income inequality.

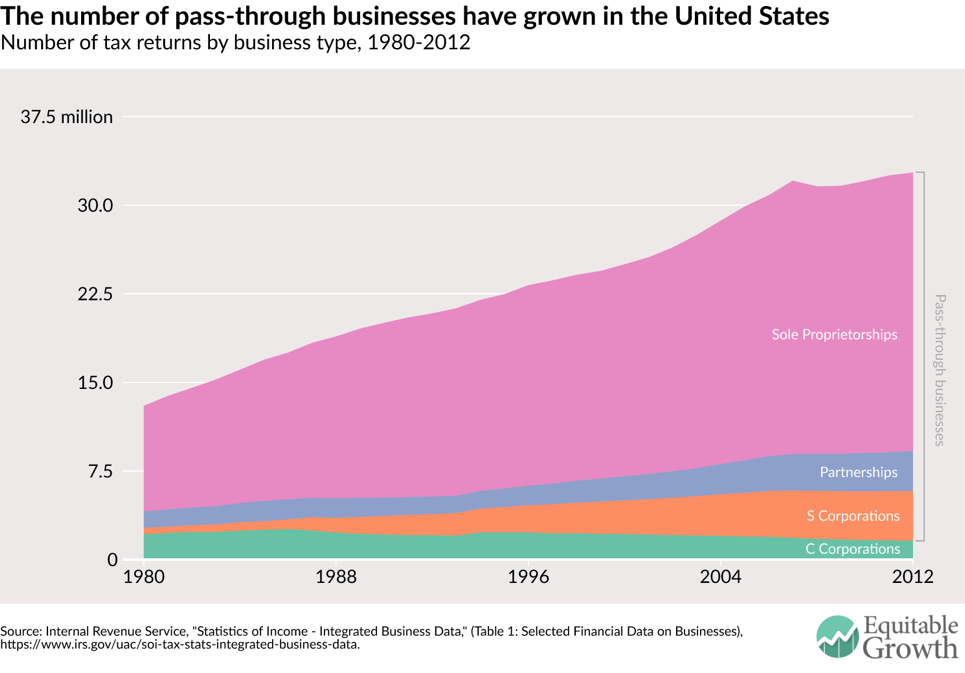

One strategy that businesses use to reduce their tax rates is to organize as a pass-through business, effectively reducing the tax base for the corporate income tax. S Corporations, Sole Proprietorships, and Partnerships are all considered to be pass-through businesses because the profits from these firms are not subject to corporate income taxes. Instead, the profits can be “passed-through” to the business owners and taxed only on their individual income tax returns. In contrast, owners of traditional C Corporations face two taxes: a corporate tax on profits and a tax to shareholders on profits that are distributed as dividends. The clear advantage of setting up as a pass-through business has greatly motivated owners to find loopholes, which has augmented their presence in the United States. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Another strategy that businesses are increasingly using is corporate profit shifting. Corporate profits, for example, can be shifted out of the United States by increasing intercompany loans, setting high transfer prices, or using a process known as corporate tax inversion. According to research by Kimberly Clausing of Reed College, who uses data from the U.S. Commerce Department’s Bureau of Economic Analysis, corporate profit shifting in 2012 alone reduced tax revenues by between $77 billion and $111 billion.

Again, if all current laws and tax codes remain unchanged, the Congressional Budget Office predicts these strategies will be used at a greater rate and corporate tax revenue will continue to stagnate as a share of GDP and actually fall relative to total corporate profits in the economy. But, with tax reform looming as a top priority for the Trump Administration and Congress, business may not stay as usual.

Speaker of the House Paul Ryan’s blueprint for tax reform—the likely template for Congress—would make several major changes to the corporate income tax code that would slash corporate tax revenues over time. Some of these changes include reducing the marginal tax rate on corporate profits from 35 percent to 20 percent and capping the tax rate on pass-through business profits at 25 percent. A recent analysis of the House of Representative’s plan by the Tax Policy Center found that if the House blueprint were implemented, $3 trillion in tax revenue would be lost over the next ten years. The TPC estimates that close to two-thirds of those losses would come from changes to the corporate tax code. What’s more, there is skepticism that the Ryan plan would lessen incentives for creating pass-through entities or fully stop U.S. corporations from shifting their profits to earn most of their income overseas in the first place.

Whether laws and tax codes remain the same or are reformed according to the House blueprint, it is clear that over the next decade corporate tax revenues need to be better preserved. Given that corporate taxes are one of the most progressive taxes in the federal system, policymakers must consider a way to recoup these losses or else we’ll be saddled with even wider income inequality.