U.S. labor market data reveal that different job characteristics contribute to the gender wage gap

Overview

In 2003, women in the United States earned on average approximately 80 percent as much as U.S. men did per hour. By 2024, the gender pay gap had grown to 84 percent, after peaking at around 86 percent in 2022. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Yet the gender wage gap is not equal across all occupations in the U.S. labor market. Female financial service sales agents, for example, currently make 52.7 percent of their male counterparts’ earnings on average, while women working in media and communications make on average 12.9 percent more than men in their field.

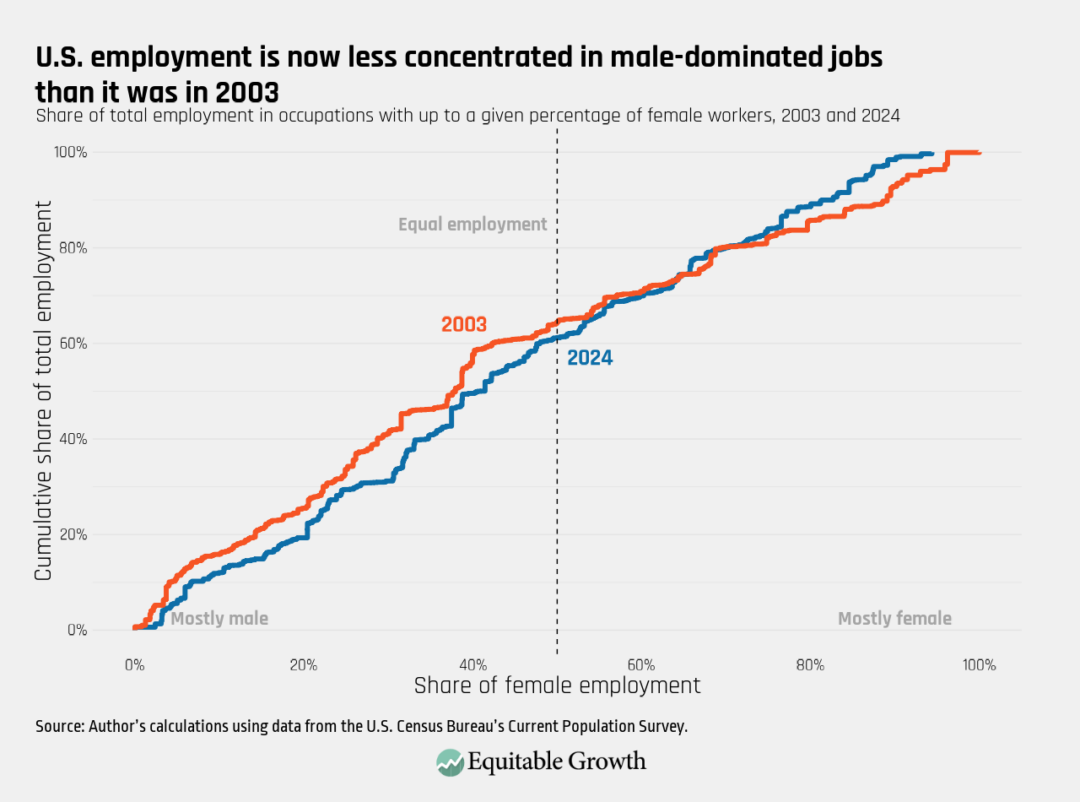

The gender wage gap changes across occupations because men and women have not been equally likely to work in all occupations—though this is less true now than it was 20 years ago because occupations have become more gender-balanced since 2003. Figure 2 below shows the share of all workers who are in occupations with a given percentage of female workers, with the left side of the graphic being more male-dominated jobs and the right side being female-dominated occupations. Each line represents the percentage of workers who are employed in occupations that have up to a given percentage of female workers. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Figure 2 suggests shifts in employment over time: The 2024 line has a lower percentage of employment that is majority male than the 2003 line and a (mostly) higher percentage of employment that is majority female. In 2003, for example, 64.4 percent of workers were employed in occupations that were 0 percent to 50 percent female. These shifts suggest that overall U.S. employment has moved toward more gender-balanced or female-majority occupations since 2003.

Figure 2 also demonstrates that, despite these shifts, many U.S. occupations are still dominated by males. Indeed, in 2024, fewer than half of all U.S. workers were employed in occupations with either equal male-female employment or majority-female employment.

So, why are women more likely to work in some occupations than others? Aside from previously studied factors, such as differences in education and treatment in the workplace, some of the answer may be found in what makes a job “good” for women workers, compared to the broader workforce. As such, examining the gender wage gap across occupations by job content is helpful.

Using O*NET data to study the gender wage gap

Data from the Occupational Information Network, or O*NET, provides insight into which worker tasks and talents are valued in different occupation. O*NET measures the degree of importance and complexity for 128 skills, abilities, and work activities for approximately 970 occupations in the U.S. labor market as of 2024. Looking at these elements can tell us more about how the jobs done by women and men differ and how these differences affect income.

The importance of various abilities, skills, and work activities to the average worker of an occupation are quantified by O*NET on a scale of 1 to 5 and are available for the years 2003 to 2024. By consolidating U.S. Census Bureau data with O*NET metrics, one can see how importance scores differ for men and women and how those differences have changed over time. This gender-importance gap is calculated by averaging the importance value of each O*NET element across occupations, based on employment by gender, then subtracting the women’s scores from the men’s. Positive values indicate that an element is on average more important in men’s jobs, while negative values indicate that an element is more important in women’s jobs.

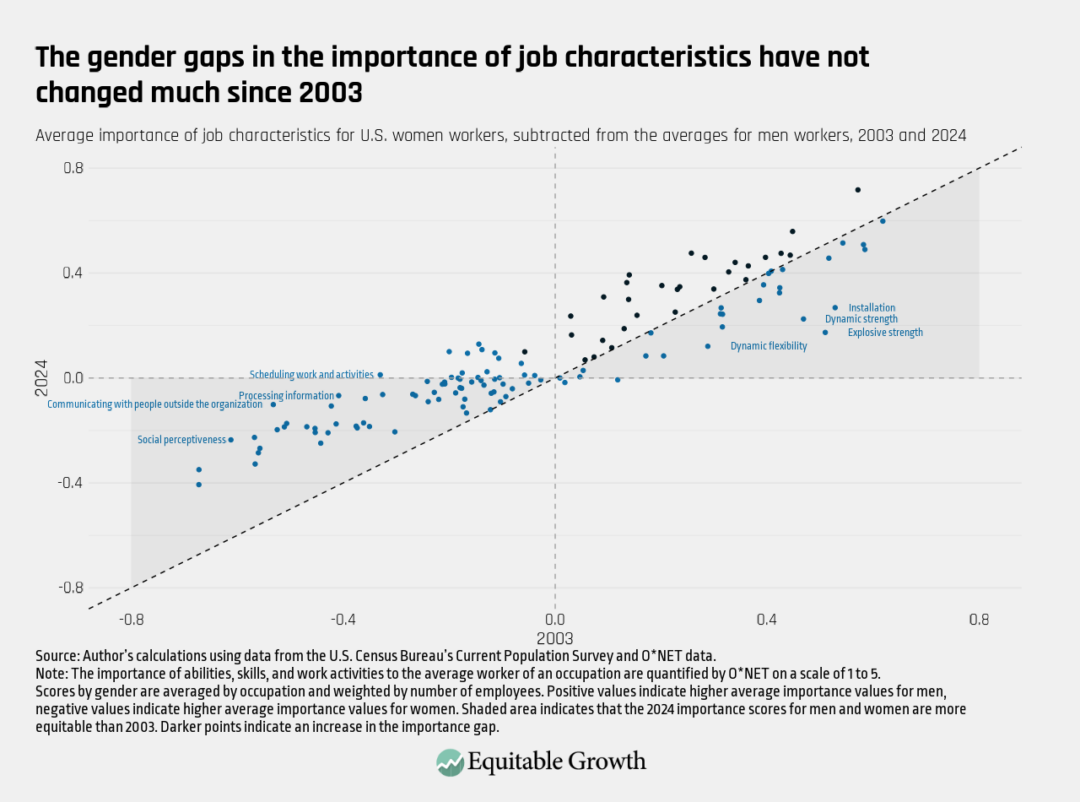

We find that the skills, abilities, and activities correlated with higher wages for women are different than those for men, and that changes to these differences over time have contributed to the reduction of the hourly wage gender gap. Figure 3 charts the 2024 importance gap against its 2003 equivalent, with each point representing a different O*NET element. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

As Figure 3 shows, there is consistent grouping close to the 1:1 line of correspondence—the dotted diagonal line—indicating that few gaps in element importance have changed much over the past 20 years. In fact, of the 128 O*NET elements, only 29 have larger gaps of importance now than they did before, as seen in the darker points on the figure. Most of the elements have 2024 importance scores that are more equitable across gender than 2003 and fall within the shaded areas. For the few points that are both lighter blue and in unshaded areas, the overall importance gap shrunk, but the sign of the importance gap changed. For instance, the gap was negative in 2003 but positive in 2024. On average, reductions in the importance gaps were more profound than increases.

Interestingly, the elements that were once more valued in high-female-employment occupations but are now valued similarly across both high-female and high-male occupations are primarily social skills and administrative tasks, such as “social perceptiveness” and “scheduling.” Conversely, the elements that were most valued by high-male occupations and have now more narrowed importance gaps consist of physical movement or strengths, including “dynamic flexibility” and “explosive strength.”

Differences in gender-importance scores make sense, given the sorting by gender that occurs in certain occupations. In 2024, for example, the most important work activity in high-female occupations was “getting information.” Two occupations that highly value this activity are medical assistants and speech-language pathologists, both of which were 90 percent female in 2024. Conversely, 2 percent of electricians were women in 2024, reducing the average valuation of “installation” skills. This sorting, and how it has shifted since 2003, offers a potential explanation as to why certain types of elements display importance gaps.

Figure 3 illustrates that jobs with different employment ratios value job characteristics differently. Our recent column on how the content of different jobs affects wages demonstrated that job characteristics can in fact impact earnings, but did not touch upon whether the aspects of an occupation that increase men’s wages are the same as those that increase women’s wages. In other words, are workers’ daily tasks—and the skills needed to perform them—valued equally by gender?

How job characteristics affect the gender wage gap

We find that the job characteristics that predict the greatest changes in women’s hourly wages are indeed, at times, different than those characteristics that predict the greatest changes in men’s wages. What’s more, when an element does impact both women’s and men’s wages, the degree of these impacts differ by gender and are not stable over time.

To come to these findings, we performed linear regressions on women’s wages from 2022–2024 on the 128 O*NET elements, with controls for worker demographics and industry. We then repeated the regressions for men’s wages and performed the same regressions by gender for the years 2003–2010. The years 2003 through 2010 contain the same U.S. Census Bureau measurements, which allow for ease of aggregation. The same is true for the 2020s, but we dropped 2020 and 2021 to remove any potential distorting effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

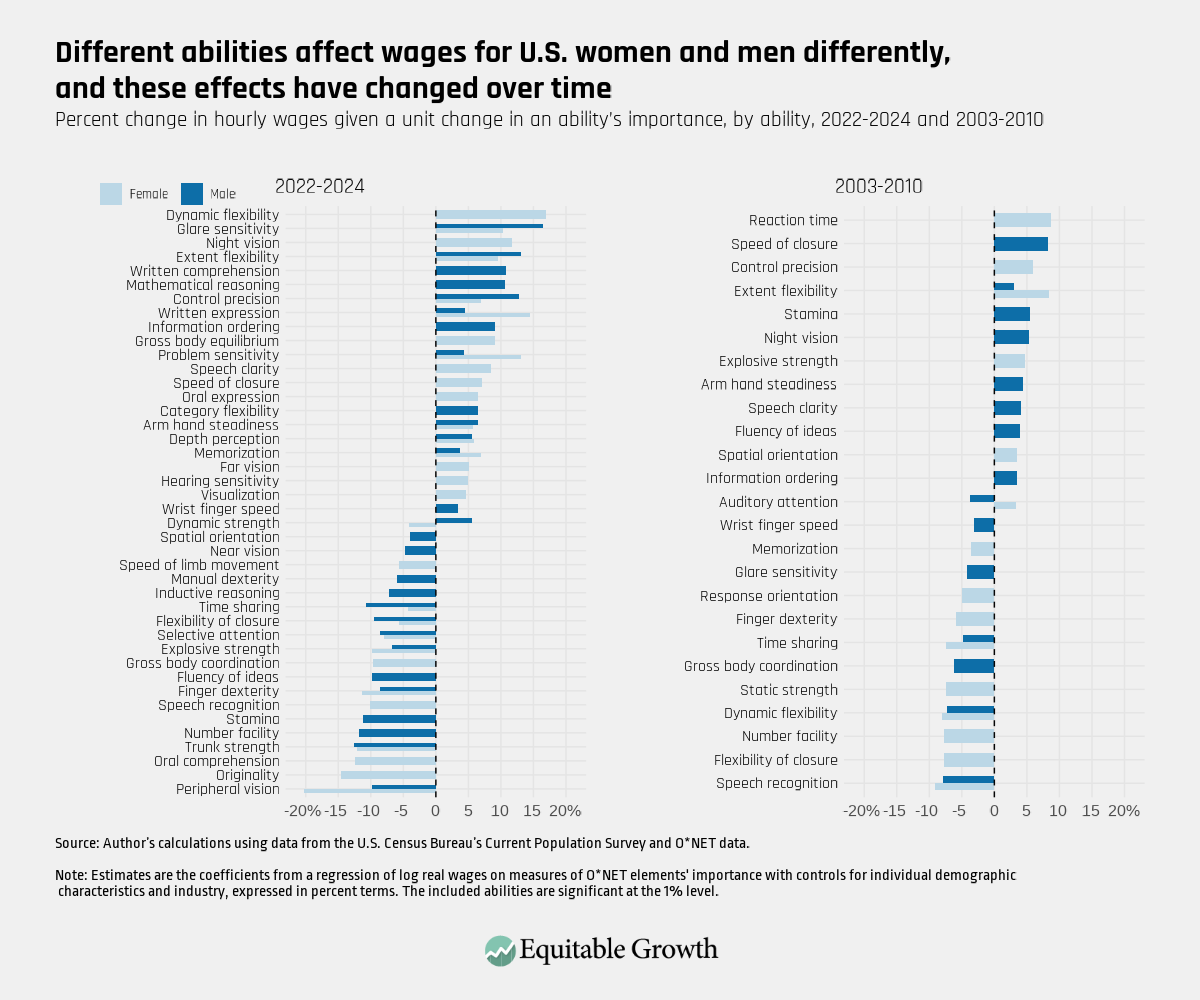

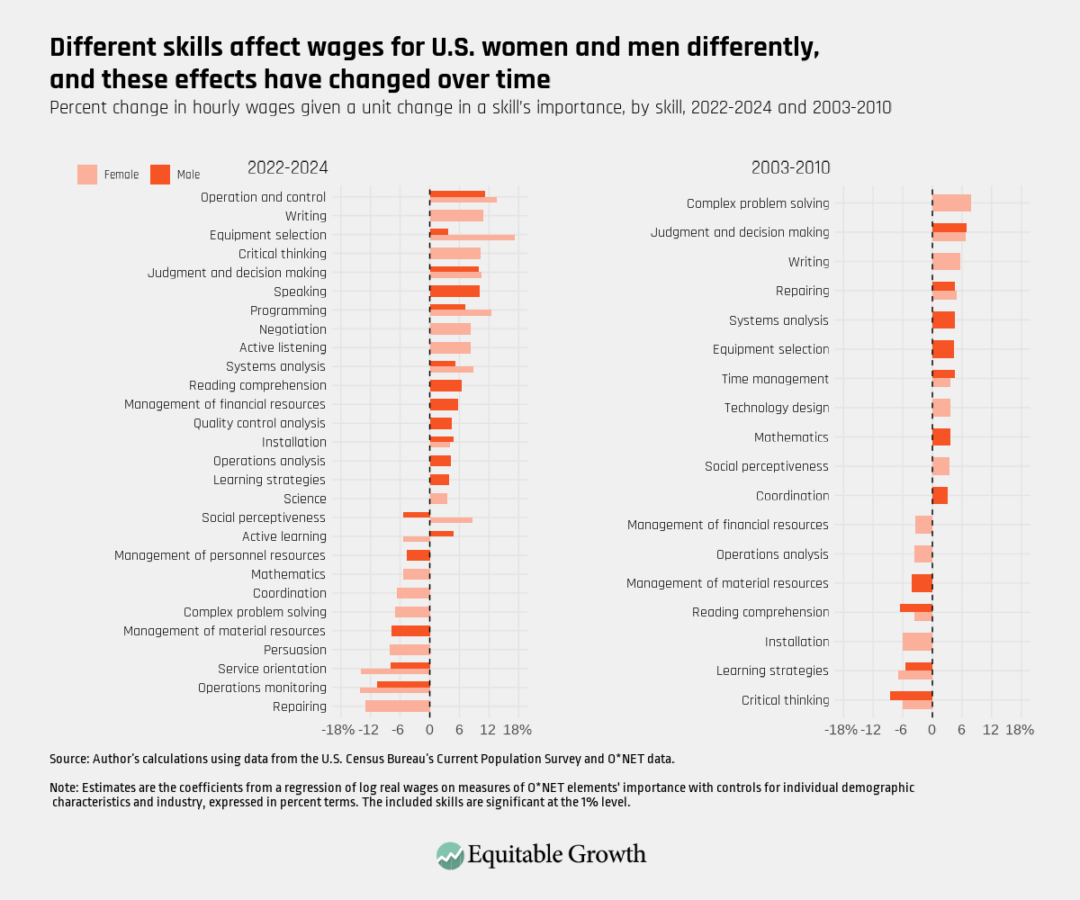

For visual ease, the results are split by three O*NET domains: abilities, or the permanent talents that can help people do their jobs (seen in Figure 4); skills, or the capabilities people develop that help them learn or do their jobs (seen in Figure 5), and work activities, or sets of similar actions or tasks performed together across different occupations (seen in Figure 6).

Figure 4 below shows that of the 52 abilities measured by O*NET in 2024, 42 of them currently impact wages at a statistically significant level. Sixteen of these abilities—including “extent flexibility,” “memorization,” and “written expression,” among others—influence the wages of both genders, albeit differently. In nearly all of these cases, the importance of these abilities either reward the wages of both genders or penalize both, with the exception of increases in the importance of “dynamic strength,” which positively affects men’s wages, while women’s. In addition to these common abilities, women have 14 unique elements, while men have 13. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

Figure 5 below illustrates how different skills affect wages differently for men and women and how those gaps have changed since 2003. There are 35 skills in the O*NET database. Twenty-eight of these skills predicted women’s and men’s wages in 2024, 10 of which men and women have in common, including “equipment selection,” “operations monitoring,” and “programming.” Only two skills—“social perceptiveness” and “active learning”—affected men’s and women’s wages differently. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

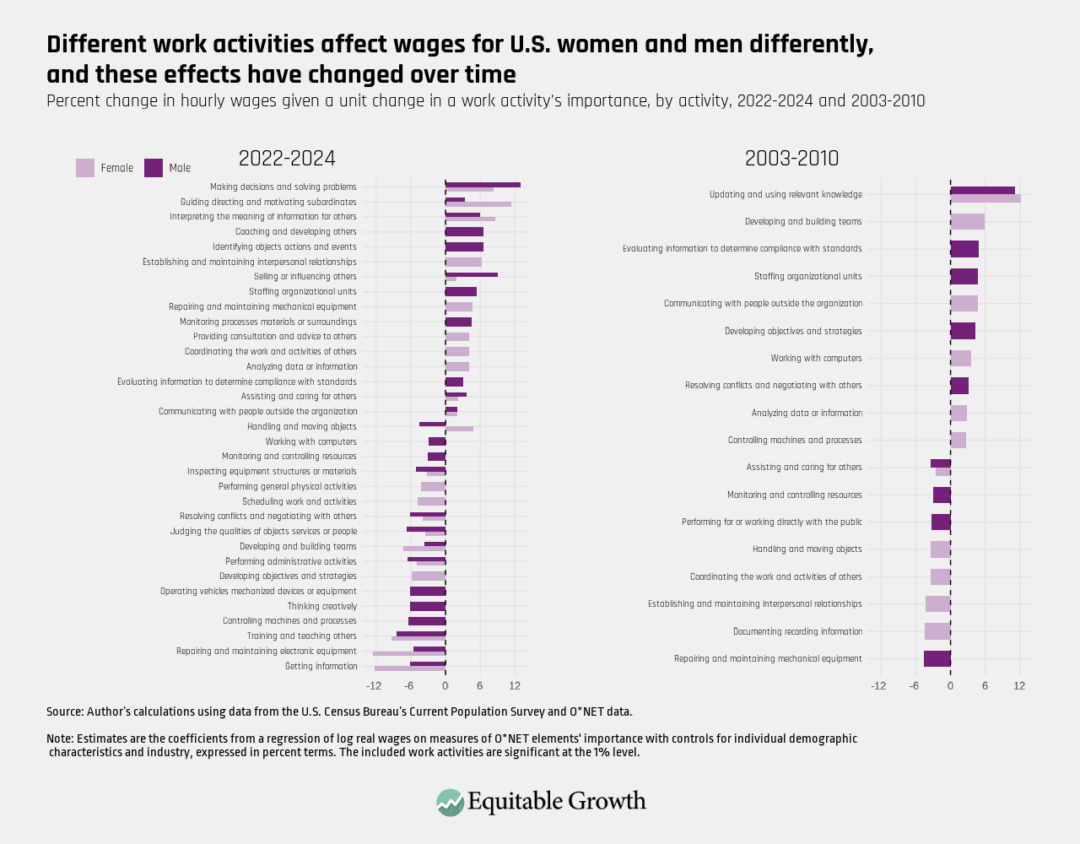

Figure 6 below represents the effect of work activities on wages. Of the 41 O*NET work activities, 33 are statistically significant factors that affect women’s and men’s wages. Less than half these work activities are shared between genders, however, and only one—“handling and moving objects”—currently affects each gender’s wages differently. See Figure 6.)

Figure 6

One key takeaway from Figures 4 through 6 is that the O*NET elements influencing women’s wages tend to have a greater impact than those influencing men’s wages. Across abilities, work activities, and skills, the range of effects is higher for women than men. On average, as the importance of job characteristics increase, women’s wages both rise and fall more than men’s wages.

Additionally, the way these elements have changed over time is similar, in the sense that there is a different set of important abilities, skills, or work activities that are relevant to women’s and men’s wages in 2003–2010 versus 2022–2024, though there is some overlap. Furthermore, the early lists consist of fewer elements that impact wages, and these elements are much less likely to overlap by gender.

The effect of job characteristics on the gender wage gap over time

The nature of men’s and women’s work, how they perform it, and its impact on wages have all changed since 2003. But to what extent do these differences contribute to the gender wage gap, and how has this relationship changed?

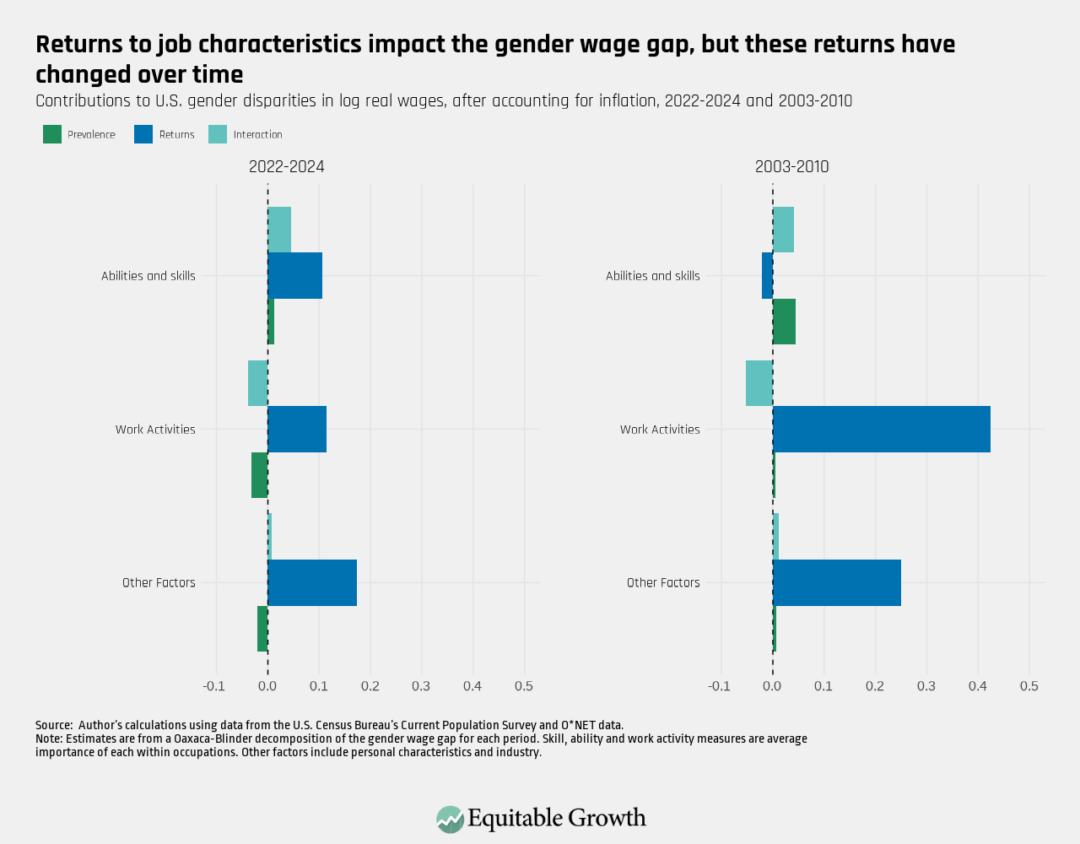

Figure 7 below presents the results of a Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition, which breaks down the wage gap into three components—differences in the prevalence of certain job characteristics by gender, differences in the returns to those characteristics, and the interaction between the two—for the periods 2003–2010 and 2022–2024. (For visual simplification, the effects of abilities and skills are combined.) The results show the impact of worker talents and tasks, as well as other demographic and industry factors. (See Figure 7.)

Figure 7

The data suggest that for both periods of time, the gender wage gap is largely driven by differences in returns to job characteristics, rather than by differences in the prevalence of those characteristics in certain occupations. In 2024, work activities and other factors contribute to the wage gap less than they did before. Conversely, worker talents (abilities and skills) now contribute to, instead of mitigate, the gender wage gap. The findings reveal that differing returns to job characteristics have been and continue to be a nontrivial component to gender wage disparities.

Conclusion

Gender employment ratios, job characteristics, and how they can predict disparities between women’s and men’s earnings have all fluctuated over time. Job characteristics meaningfully influence differences in wages across occupations but also are a key component in shedding light on differences in wages across gender. Incorporating these findings into established explanations might offer more clarity into shifts in the U.S. labor market and how those, in turn, may account for the gender wage gap in the 21st century.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!

Stay updated on our latest research