The new overtime rule is “good economics and good business”

Millions of Americans may soon be getting a raise, or at least will gain more time away from the office after a standard 40-hour workweek. The Department of Labor is set to issue a final ruling to expand the Fair Labor Standard Act’s overtime coverage today, making salaried workers earning up to $47,476 a year eligible for time-and-a-half pay if they work beyond a 40-hour week. The Obama Administration estimates that the new regulations, which go into effect on December 1st, will extend overtime protections to more than 4 million workers (with others estimating more).

The ruling is the first substantial update to the threshold since 1975, which covered 62 percent of salaried employees at the time. But because the overtime rule was not tied to inflation, today’s current threshold of $23,660 is below the poverty line for a family of four and covers only 7 percent of the salaried workforce. The updated provision allows for future increases every three years.

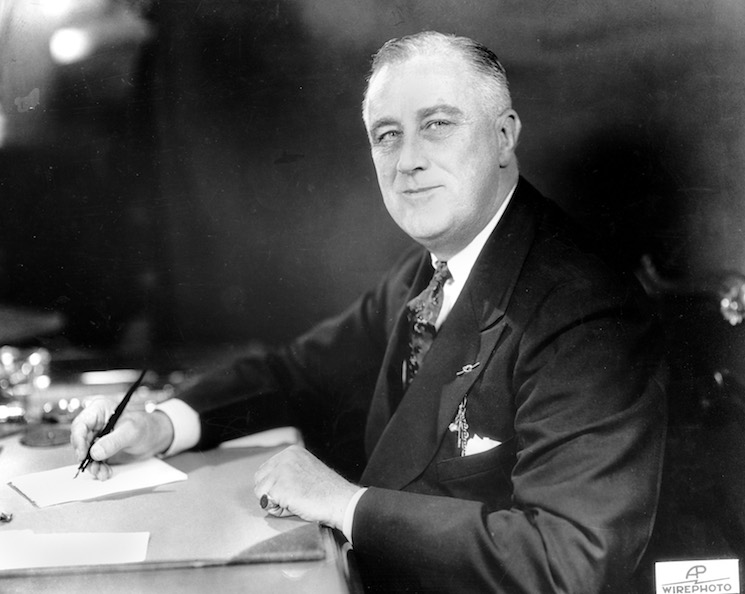

The new rule will obviously help individual workers, but these work-hour protections also deliver significant benefits for the entire economy as well. When the Fair Labor Standards Act was first enacted in 1938 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the height of the Great Depression, champions of the overtime provision argued that it would not just mitigate overwork but also encourage employers to “spread the work” by hiring more people working fewer hours. Roosevelt also urged businesses concerned about the initial cost of hiring more workers to consider that increasing employment would indirectly inject some much-needed cash into the struggling economy. As Roosevelt said in 1933:

I ask that managements give first consideration to the improvement of operating figures by greatly increased sales to be expected from the rising purchasing power of the public. That is good economics and good business. The aim of this whole effort is to restore our rich domestic market by raising its vast consuming capacity.

Today’s economy differs from that of the 1930s, yet, in an economy that is not operating at full capacity, this policy is likely to put more money into workers’ pockets. A bigger paycheck boosts their ability to buy goods and services—a key economic engine for domestic growth. That is because workers that will benefit from these policies are more likely to spend the extra money they earn.

Even if employers respond to the new overtime rules by limiting hours, which has been cited as a criticism of the new regulations, the extra time workers gain—time spent investing in one’s health, education, community, or family– may be just as valuable to some workers. Exhaustion from overwork takes a detrimental toll on one’s mental and physical health, relationship, or even one’s children. That may be why, when University of Pennsylvania, Abington’s Lonnie Golden undertook a 2013 survey of 1,000 adults, he found that one in five workers would take a 20 percent pay cut in exchange for one fewer day of work.

Because there are a certain number of fixed costs associated with each individual employee, it may seem like a cost-effective business strategy to have fewer employees work longer hours, especially if an employer does not have to pay them overtime. But Stanford University’s John Pencavel finds that, generally speaking, a worker’s output drops sharply if they routinely work beyond 49 hours a week (even if you think you are getting a lot done). If you tend to stick around the office late at night on a routine basis, you are getting little work done at the expense of your own well-being.

This costs companies money. One study contends that in 2007, fatigued workers cost employers more than $100 billion annually in lost productivity. Overtime also raises the rate of mistakes and safety mishaps, which put the general public at risk. Federal regulators, for example, found that a truck driver’s extreme fatigue due to many hours on the road was the main causes in the crash that killed comedian James McNair and critically injured Tracy Morgan.

More standardized work hours also make it easier for those with outside obligations to navigate the demands of work and life, which has implications on a national scale: When employers require long hours, it means they are less likely to hire those with caregiving or other outside responsibilities. Because women still take on the bulk of the caregiving responsibilities, long hours may push some women out of the workforce. This doesn’t just harm female workers: Because women are graduating from college and graduate school in higher numbers than men, employers miss out on the opportunity to hire the most qualified people for the job.

Fewer women in the labor market also harms the economy as a whole. Research by Equitable Growth’s Heather Boushey and John Schmitt, and Eileen Appelbaum at the Center for Economic and Policy Research found that that U.S. gross domestic product would have been about 11 percent lower in 2012 if women had not increased their working hours as they did since 1979. That translates to $1.7 trillion less in output—similar to what the combined U.S. spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid in 2012.

There is no doubt that workers and their families cannot succeed without hard work. But we must be more mindful of the consequences for individuals, businesses, and the economy alike associated with working without limitations. The new overtime rule, which will disproportionately help women, workers under 35, African Americans, Hispanics, and workers with lower educations, is an important step.