The historical lessons from the U.S. General Property Tax

In the early 19th century, a new type of property tax system emerged in the United States, distinguishing itself from its European counterparts by encompassing all forms of property. This tax system, known as the General Property Tax, went beyond the land-based taxes prevalent in Europe and the United States at the time and even included personal and financial wealth. It essentially functioned as one of the earliest versions of a wealth tax.

For almost a century, the General Property Tax was a cornerstone of the U.S. political and economic infrastructure, contributing a significant portion to the revenues of state and local governments. Unlike the European model, which relied more on central government funding, the General Property Tax showcased the American emphasis on local revenues to finance local government.

The prominence of the General Property Tax waned after the 1930s, however, as it was gradually supplanted by different forms of taxation, including the income tax and the sales tax in the early 20th century and a shift of activity from the local and state governments to the Federal government with large-scale new programs such as the New Deal. Today’s property tax in the United States is focused solely on real estate, the value of which varies greatly from region to region, state to state, and county to county across the nation.

An unintended byproduct of the General Property Tax was the detailed documentation it created, which provides a rich, granular historical dataset on U.S. wealth. Drawing on many primary and secondary sources, our new working paper constructs a new dataset that allows us to chart the evolution of national wealth from 1800 to 1935. We provide a comprehensive, localized measures of wealth at state and county levels. The dataset also enables us to study three fundamental issues:

- The trajectory of wealth accumulation during a crucial era of U.S. economic development

- The distribution of wealth across different regions of the country

- The factors that influenced the local growth of capital

Let’s briefly present all three of these findings detailed in our new working paper.

The immediately striking revelation from the dataset is the rapid acceleration of the growth in national wealth following the Civil War. This is especially evident in regions outside of the South, where stagnation contrasts sharply with the rest of the nation’s prosperity.

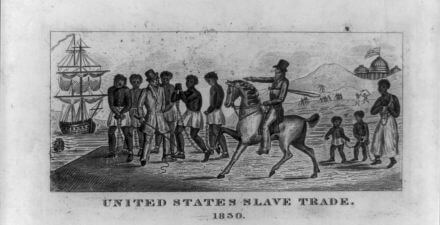

At first glance, wealth per capita in the Northeast, Midwest, and South before the Civil War was relatively similar, but this was in large part due to the institution of slavery. Enslaved Americans were regarded as the personal property of their enslavers, implying that Southern states’ wealth figures before emancipation were significantly inflated.

Once we adjust for this by excluding the value of those who were enslaved, the economic realities of Southern states such as Georgia, Florida, and Alabama look starkly different. More than half of these three states’ property was tied to enslavement. As a result, the wealth of White inhabitants in the Southern states seemed much greater than their Northern counterparts due solely to the institution of enslavement.

Furthermore, we find that per capita property value in Southern states experienced a significant decrease, more than 25 percent, from 1860 to 1870, even after the value attributed to enslaved Americans is subtracted. And these negative effects of slavery on the economic development of the South persisted for decades after the Civil War.

Even after considering various geographical, demographic, economic, and inequality factors, counties in the South that had the highest proportion of wealth tied to enslavement saw significantly slower growth over the long term, spanning the 60 years from 1870 to 1930.

The persistence of spatial wealth inequality after the Civil War is another finding. Despite migration flows and increased integration of the U.S. national market, the level of spatial inequality remained high until 1930 and beyond. The wealth hierarchy of counties and states remained largely unchanged, and the share of national wealth possessed by the top 10 percent of counties saw an uptick.

What contributed to the relative wealth of different regions after the Civil War? And why did some areas accumulate wealth faster than others? Our dataset provides some intriguing answers. Geographic features such as climate, topography, soil productivity, and coastal proximity played a significant role in shaping initial wealth and subsequent growth. Other factors, among them literacy rates and population density, also had significant impacts on wealth accumulation.

As regions evolved economically, a trend reminiscent of broader national development emerged. Wealthier regions exhibited lower agricultural employment and a higher concentration in commerce. Manufacturing saw an initial rise and then a decline as regions grew richer.

An important finding in light of the renewed debate about inequality is that wealth inequality within individual counties across the country was negatively correlated with long-term property growth. This correlation remained even when accounting for geographic, demographic, and economic factors. This local-level finding reinforces the broader literature examining the link between inequality and growth. One notable mediator in this relationship was human capital. Regions with higher inequality experienced lower increases in literacy rates.

In sum, the rich information revealed by the historical sources of the General Property Tax that we compiled in this new dataset of localized measures of wealth offers interesting new insights on the determinants of wealth accumulation and should continue to prove useful to economists, historians, and policymakers alike.

— Sacha Dray is an economist at The World Bank, Camille Landais is an economist at the London School of Economics, and Stefanie Stantcheva is a political economist at Harvard University.