The “Bush Boom” and the Obama Stagnation: Wednesday Focus: March 12, 2014

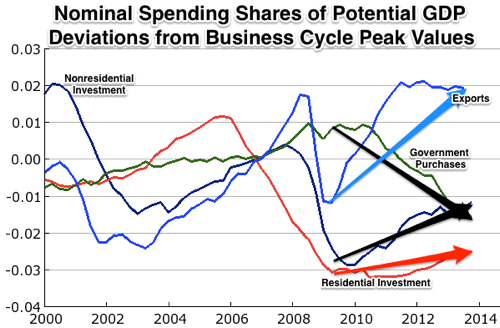

Let me start by setting out four major components of spending in the economy–spending by foreigners on exports, spending by all levels of the U.S. government purchasing goods and services, spending on residential construction, and spending by businesses on plant and equipment–all measured as percentages of potential output, and all calculated as deviations of their values from the mid-2000s business cycle peak:

The Bush Boom:

- +1.0%: Exports

- +0.6%: Government Purchases

- +0.0%: Nonresidential Investment

- +1.6%: Residential Investment

- +3.2%: TOTAL

The Obama Stagnation:

- +3.0%: Exports

- -2.3%: Government Purchases

- +1.7%: Nonresidential Investment

- +0.4%: Residential Investment

- +2.8%: TOTAL

The two crashes–the Dot-Com Crash and the Greater Crash–that preceded the <snark>”Bush Boom”</snark> and the Obama Stagnation were very different: the economic tide reached its ebb with an unemployment rate of 6.4% in 2003 after a 2% point upward leap since 2000; the economic tide reached its ebb with an unemployment rate of 10.0% in 2009 after a 5.5% point upward leap since 2007. Because of what came before, we would have expected the bounce-back to be much stronger after 2009. But it wasn’t–it has been about the same. And the big reason that it has been about the same is that government purchases grew by 0.6% points of GDP after the Dot-Com Crash came to an end, yet have fallen by 2.3% points of GDP since the end of the Greater Crash in 2009.

Export growth has been much stronger since 2009 and has carried exports up to levels unimaginable at the last business-cycle peak. Non-residential investment growth has been much stronger and has carried non-residential investment back to within 0.5% point of the same share of potential GDP it was at the start of 2006. The economy’s deficiencies lie in three areas. First, they lie in residential investment–where the singular failure of the Obama administration to take any meaningful executive action to repair housing finance or to make establishing a sound framework for housing finance a legislative priority at any level have greatly increased financial uncertainty and prevented any sort of housing finance normalization. Second, they lie in government purchases–where the Obama administration’s vain pursuit of a “grand bargain” on the long-run financing of the government has prevented it from fighting counterproductive short-term austerity. Third, they lie in the failure of other sectors to take up any of the economic slack. But why should businesses invest more when demand is still low? And how, with a Treasury still committed to the stale talking point that a strong dollar is in America’s interest, could we expect much more out of exports? And what is supposed to fuel another consumption boom with so many households still feeling overleveraged and so many others still sleeping in their sister’s basement as they try to build up another housing down payment?

When the economic history of 2002-2020 comes to be written, it will be all about at least three extraordinary self-inflicted economic disasters: the deregulation of housing and high finance and the consequent Greater Crash of 2007-2009; the failure to nationalize and then rationalize housing finance and so restore the housing credit channel at any point starting in 2009; and the extraordinary counterproductive wave of short-term austerity beginning in late 2010.

I wonder how and what the policymakers will plead in excuse? First out of the gate, of course, will be Tim Geithner’s Stress Test…