Taking a look at unpredictable schedules

The first Labor Day celebration took place on September 5, 1882 in New York City, when thousands of workers marched and took an unauthorized “workingman’s holiday” to protest the unlimited hours many workers of the era were compelled to put in. While overwork is still a problem for many Americans, a growing number of Americans are grappling with unpredictable, constantly shifting schedules, as detailed in a new issue brief today from Equitable Growth.

The first Labor Day celebration took place on September 5, 1882 in New York City, when thousands of workers marched and took an unauthorized “workingman’s holiday” to protest the unlimited hours many workers of the era were compelled to put in. While overwork is still a problem for many Americans, a growing number of Americans are grappling with unpredictable, constantly shifting schedules, as detailed in a new issue brief today from Equitable Growth.

Unpredictable scheduling is often aided by “just-in-time” scheduling software, which allows employers to generate schedules based on predicted consumer demand, accounting for factors such as time of day, weather, the season, or even a nearby sporting event. But they do so at the expense of the worker, many of whom see their schedules shift from day-to-day and are given little advanced notice of when they are supposed to show up to work

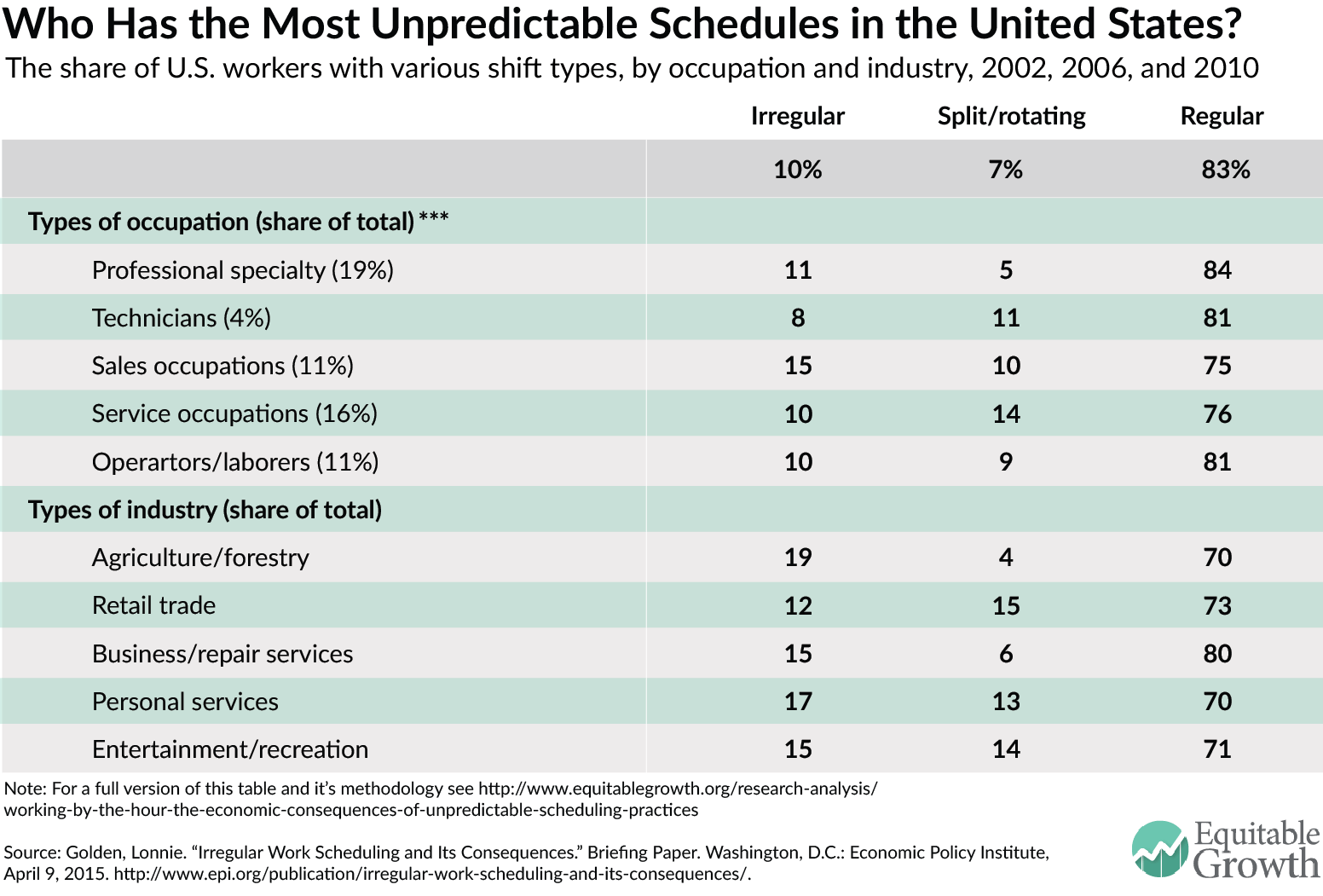

These kind of unstable schedules affect about 17 percent of the labor force, according to one study. They tend to be most common in retail and service sectors, which are some of the fastest-growing industries and also ones in which workers already face a lack of benefits, poor working conditions, and insufficient pay. (See Table 1.) What’s more, employers frequently require full-time availability to ensure there are always enough workers during busy periods but then fail to give stable or full-time hours.

Employees may spend time and money commuting to work for a scheduled shift only to be sent home without pay if business is slow. For those with children, that may mean they have to pay for childcare even if they themselves did not get paid. And within some industries, it is not uncommon for employers to require workers to remain on-call, keeping their schedules free on the chance that their employer may need them.

These practices perpetuate existing gender and racial inequalities, as workers of color—especially women of color—tend to be sorted into the low-paid positions most most affected by these unstable scheduling practices (despite sharing similar levels of education and age with their white counterparts). The volatility in hours can mean that workers may not earn enough to make ends meet, which affects family well-being as well as economic demand. Yet workers may be unable to take a second job or pursue the kind of education necessary for upward mobility because of the constantly fluctuating hours. In fact, many employees—especially those with care responsibilities—are fired or forced to quit in order to search for a new job.

As we lay out in our issue brief, this has costs for firms. While reducing labor costs may slash expenditures in the short-term, treating workers’ time as just another variable in the cost equation undermines productivity and creates high turnover rates, both of which are costly. Unpredictable schedules also affect who can take jobs and how productive workers may be on the jobs, which also has an impact on business profits.

Despite the problems, federal law does not address unpredictable schedules. But in the face of mounting pressure from employees and policymakers, many private companies have begun to overhaul their work policies. Six major retailers, for example, ended on-call scheduling after attorney general Eric Schneiderman launched an inquiry into their workforce. Wal-Mart Stores Inc., which was one of the first adopters of just-in-time scheduling practices, has announced that it is testing a new system that gives employees the choice to have fix schedules for up to six months at a time. Technology companies also are helping workers take matters into their own hands, and are creating a variety of new smartphone apps that can help employees and employers provide more schedule flexibility.

Local governments also are beginning to pay attention to this issue. After San Francisco enacted the Retail Workers Bill of Rights in 2014, which restricts employers’ ability to impose unpredictable and last-minute schedules on their employees, 18 different states and municipalities introduced similar work-hour legislation in 2015. A bill was introduced last year on the federal level as well.

Of course, legislation alone cannot completely eliminate scheduling abuses by employers, but a federal standard would provide an important marker that states and localities could improve upon and motivate the private sector to invent new ways to balance labor costs and profits.