Overview

After several decades of neglect, school desegregation by race and income in primary and secondary schools is once again a topic of conversation among policymakers at the federal level and in communities across the United States. School segregation by race was declared illegal in the Supreme Court’s landmark 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education, but it took several decades to enforce that decision across the nation. Additionally, a series of legal rulings, local efforts to resist integration, and other trends—including increasing residential segregation and economic inequality—began to slow the progress of desegregation beginning in the late 1980s. Today, students in many metropolitan areas currently experience levels of segregation and racial isolation comparable to those in the 1960s and 1970s.1

This report examines trends in racial and socioeconomic school segregation since 1954, discusses the key legal and economic drivers of these trends in school segregation through to the present day, and breaks down the empirical effects of school segregation on economic inequality, mobility, and growth. Building on this historical and social scientific context, the report concludes with evidence-backed recommendations for policymakers interested in once again desegregating schools to create a fairer and stronger economy for all students across the country and their families. Among those recommendations are:

- Reduce residential segregation via policies such as affordable housing and zoning reforms to create mixed-use, mixed-income neighborhoods

- Redrawn and/or consolidated school districts to cultivate student populations that are more socioeconomically and ethnically diverse

- Open enrollment systems that allow students to enroll in any school in their district or in nearby schools in neighboring districts

- Controlled choice procedures that allow students to attend a top-choice school, while ensuring equitable access to the highest-performing schools

- School finance reforms that equalize funding across schools and decrease school districts’ reliance on local property taxes

- Civil rights enforcement to certify that schools and school districts are not encouraging or allowing disparities in access to the best schools

- Expansion of gifted programs to a larger and more representative pool of students

Many of these reforms have already been implemented to varying extents at the federal, state, and local levels—providing concrete economic benefits to both disadvantaged students and the broader economy.

Trends in school segregation since Brown v. Board of Education

Following the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, the authorization of federal desegregation enforcement in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Supreme Court’s 1968 ruling in Green v. County School Board of New Kent County that district-level integration plans must meaningfully decrease segregation levels, the United States experienced a sharp decline in black-white school segregation, especially in the South.2 As desegregation gradually continued through the late 1980s and into the early 1990s, the pace progressively began to decelerate before slowing to a halt. Despite initial successes, the primary enforcers of desegregation—federal district courts and the federal Departments of Justice and Education—began to face headwinds in the form of changes in residential living patterns, school enrollments, Supreme Court precedents, and increasingly successful local efforts to resist integration.

The contemporary result of these trends today is a highly segregated status quo. Yet scholars disagree over whether the broad trend in segregation has been stagnation or resegregation since the late 1980s. Much of this debate hinges on which type of measure is used to assess segregation, specifically:

- Exposure measures, which estimate potential contact between racial groups in public schools

- Evenness measures, which track the extent to which the proportion of each racial group differs from one public school to the next3

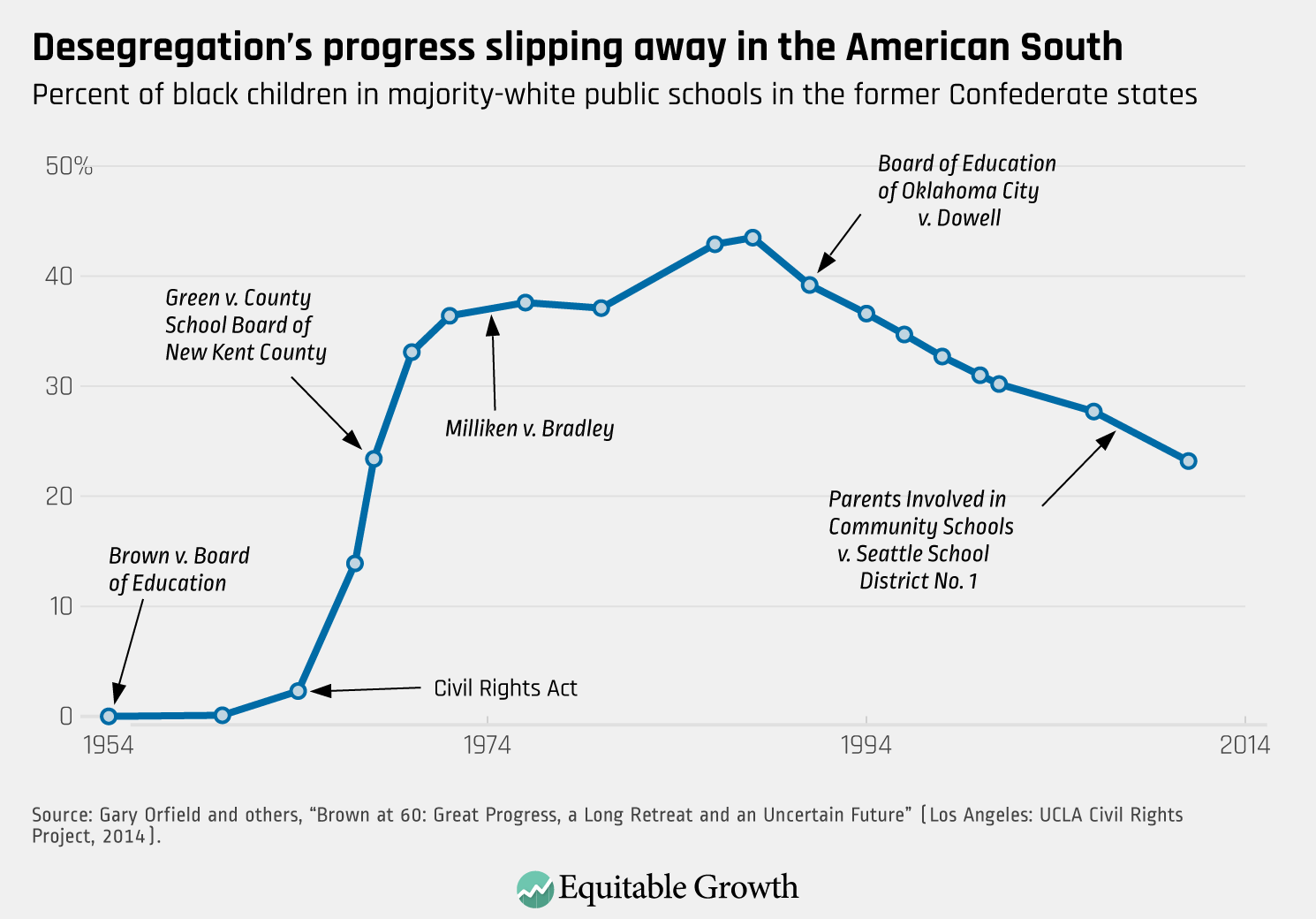

Evidence for resegregation is particularly strong in the case of the South. Using a measure of exposure—specifically, the fraction of black students in majority—white schools—University of California, Los Angeles researcher Gary Orfield, Penn State University researcher Erica Frankenberg, and other scholars find that segregation in the South (along with other regions) has increased over the past three decades. Specifically, their index of the proportion of black students enrolled in, and thus exposed to, majority-white schools in the South decreased from its peak of 43.5 percent in 1988 to its depressed level of 23.2 percent in 2011.4

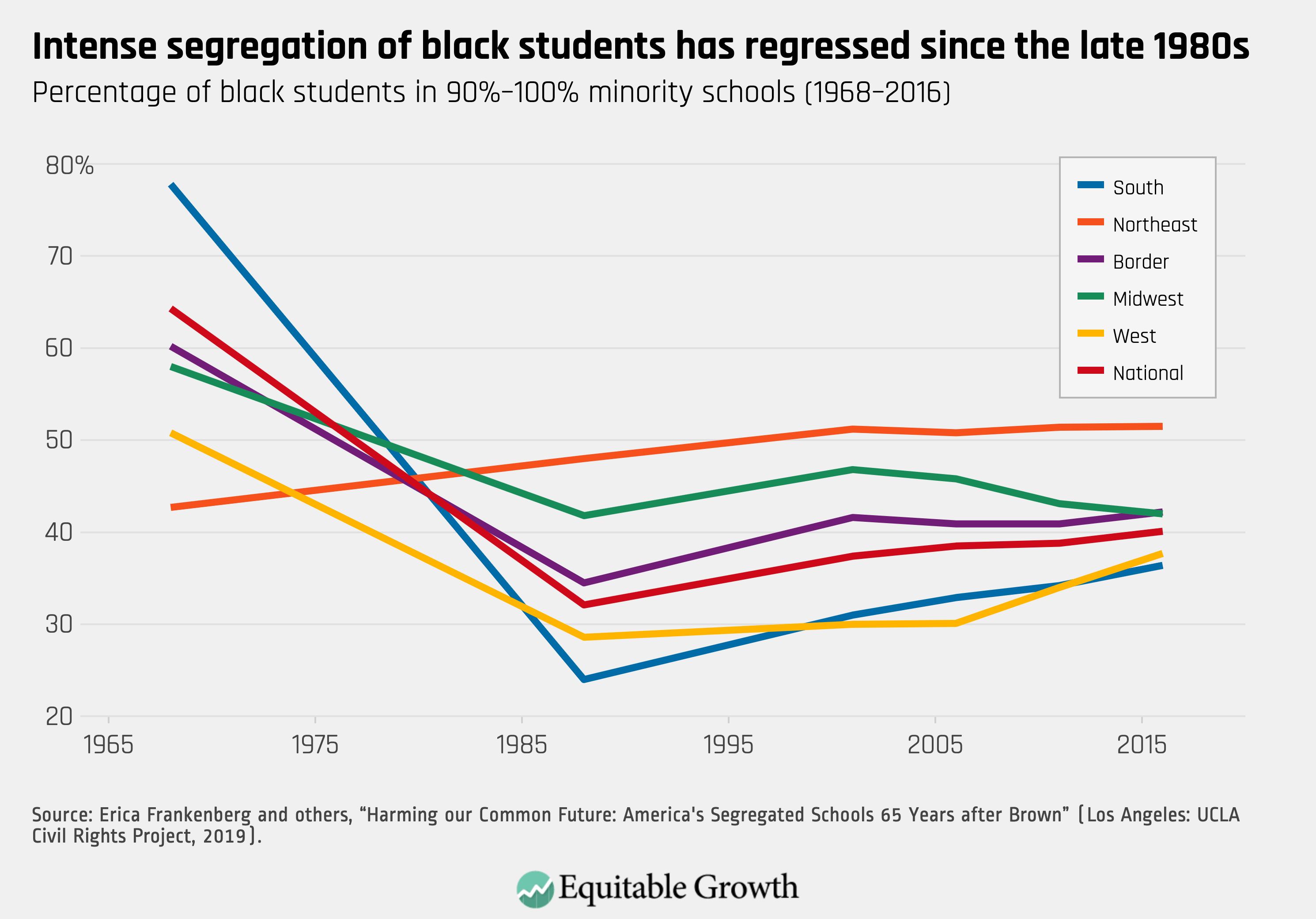

Using a measure of isolation, or lack of exposure, scholars have emphasized a particularly disconcerting concurrent national trend: the rise in “intensely segregated schools,” where black or Hispanic students represent upward of 90 percent of the total population. Although this severe form of segregation has been trending up across regions since the 1990s, it is important not to forget that the South’s huge progress in desegregation in the 1970s and 1980s has positioned it to be the least intensely segregated region for black students in the United States today. In contrast, black students in the Northeast are currently more likely to experience intense segregation than their peers in any other region. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Evenness measures tell a different story. Using a measure of unevenness—differences in the proportion of black and white students across schools—Brown University sociologist John R. Logan and other scholars argue that overall school segregation increased only slightly after 1990. But they nevertheless acknowledge a continuing increase in segregation between school districts from the 1970s through the 1990s—a trend which limited many of the early gains of desegregation.5

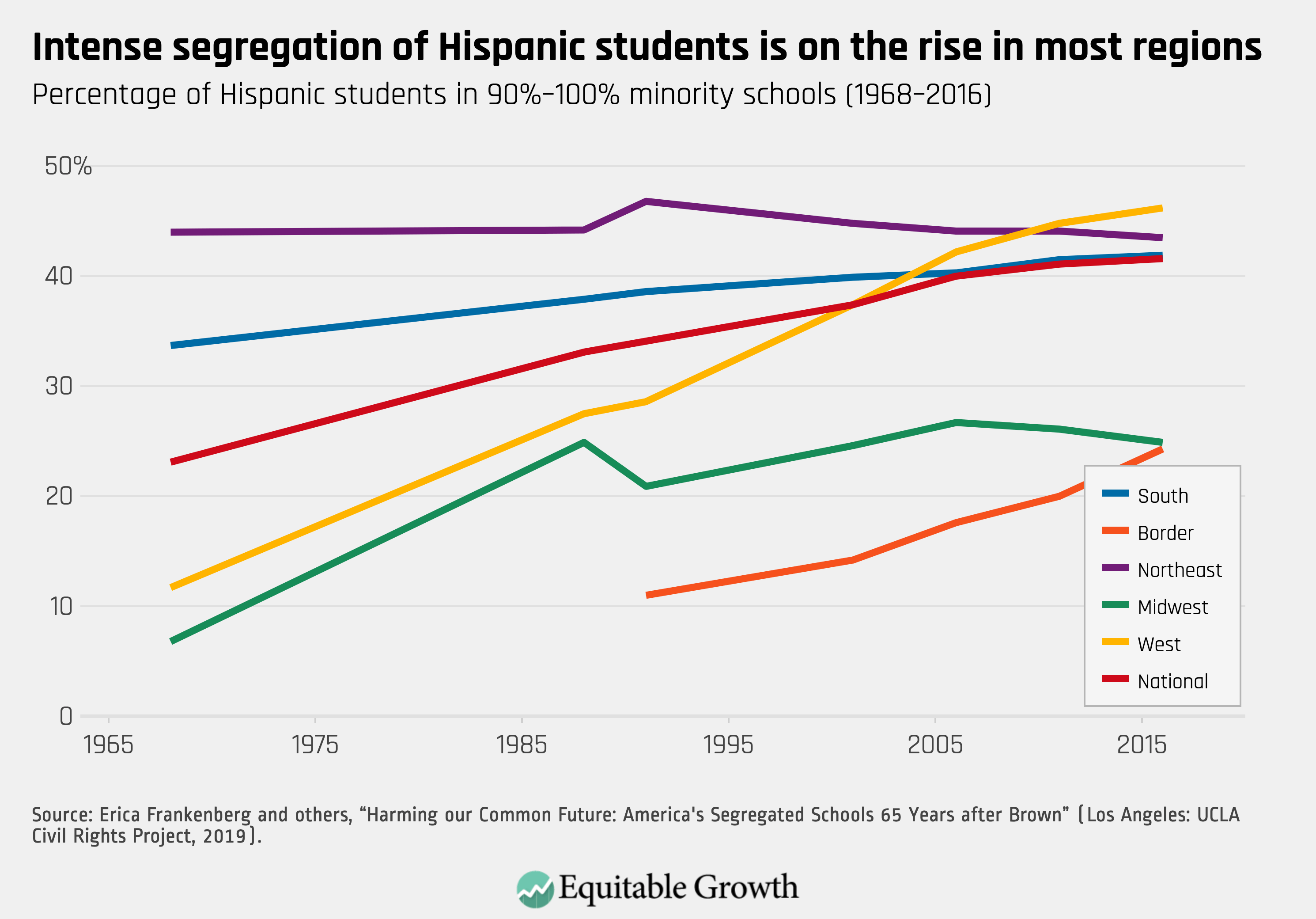

The story is similar for Hispanic students, who initially faced lower levels of segregation than their black peers but are currently in a similar situation. Using exposure metrics, Orfield and his colleagues calculate steadily increasing levels of segregation of Hispanic students from whites over the period from 1968 to the present. Yet scholars using evenness measures estimate smaller relative increases in Hispanic-white segregation in the 1990s and 2000s. Either way, it is clear that the segregation of Hispanic students has worsened notably in recent decades. Furthermore, like black students, Hispanic students today experience heightened levels of intense segregation. (See Figure 2).

Figure 2

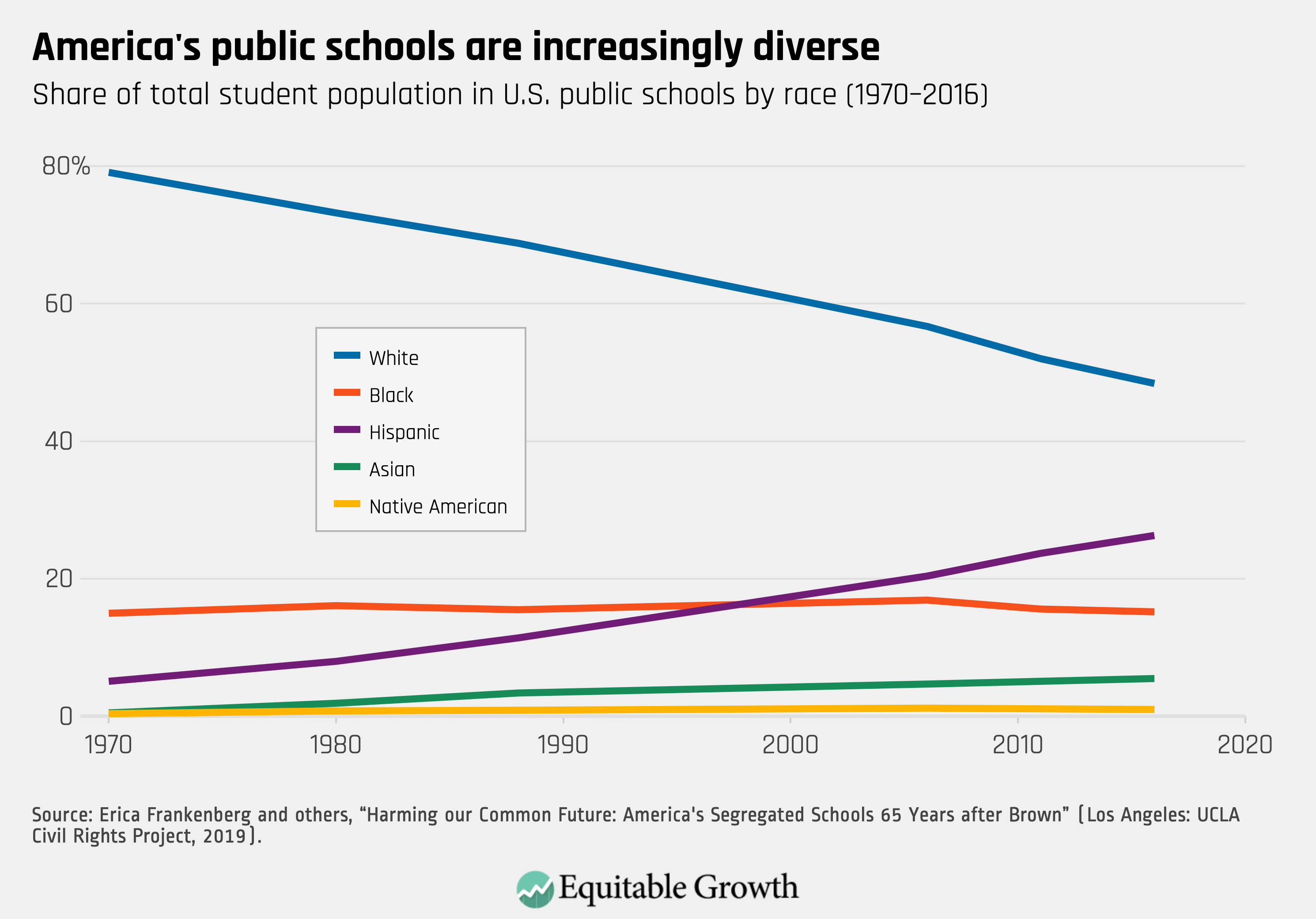

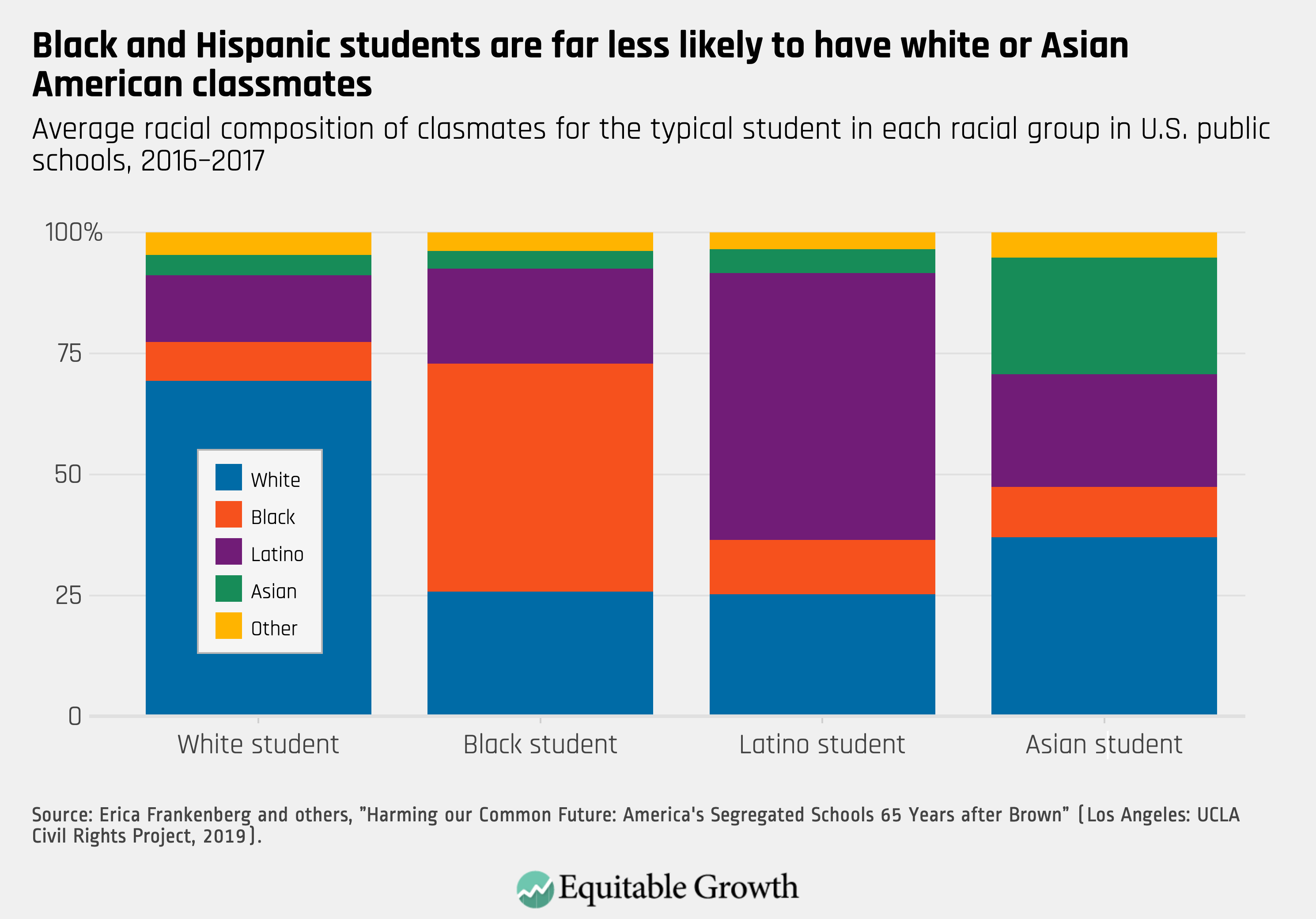

While Asian students also experience educational segregation, they are significantly better off, on average, than their black and Hispanic peers. Today, researchers estimate that black students are twice as segregated as their Asian American counterparts and 20 percent more segregated than Hispanics.6 Furthermore, whereas black and Hispanic students are more likely to be concentrated in high-poverty schools, Asian students, like their white counterparts, are most frequently found in middle-class schools.7 (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

The central explanation behind the divergence in evenness and exposure measures of school segregation is the growing diversification of the overall student population in the American public school system.8 This trend has made schools less segregated from an evenness perspective, as racially concentrated schools with low percentages of white students are increasingly reflective of the shrinking share of white students in the overall population.

Conversely, in the absence of public policies encouraging integration, the diversification of the overall student population has worsened exposure measures of segregation, as black and Hispanic students are increasingly concentrated in schools with other black and Hispanic students without much exposure to white and Asian American classmates.

This distinction is the reason why a growing number of U.S. students attend schools with classmates of different races, yet, at the same time, black and Hispanic students are most likely to live in districts and attend schools where the overwhelming majority of the student population is black or Hispanic.9 While both evenness and exposure measures of segregation are valuable, the recent rise in exposure-based measures of segregation and racial isolation should be of particular concern for policymakers insofar as the benefits of integration described in further detail below are derived from opportunities for exposure to different racial and socioeconomic groups.

One trend that is substantiated by both exposure and evenness measures of segregation is the sharp rise in income-based segregation since the 1970s. Today, the U.S. income distribution is increasingly polarized, with the middle class hollowed out, the wealthy registering big gains, and poor and working-class workers and their families slipping behind.10 While this trend has worsened income-based school segregation, measures of educational segregation by income have risen in recent decades, even when controlling for rising economic inequality. Specifically, sociologists Ann Owens of University of Southern California, Sean Reardon of Stanford University, and Christopher Jencks of Harvard University have found statistically significant increases in between-district and between-school segregation by income between 1990 and 2010—with the former currently responsible for two-thirds of contemporary socioeconomic segregation in metropolitan areas.11

While increasing income-based educational segregation limits educational opportunities for working- and middle-class students of all races, black and Hispanic students who face “double segregation” by both race and income are most affected. Indeed, Orfield, Frankenberg, and their co-authors find that half of the public schools that are 90 percent to 100 percent black and Hispanic likewise have a student population that is 90 percent to 100 percent from low-income households.12

Historical and contemporary causes of persistent segregation

This part of the report addresses the social scientific explanations for persistent educational segregation since the late 1980s. These causes largely fall into two categories. First, changes in living patterns, school-district boundaries, and public school enrollments have altered the underlying demographics of the population of students enrolled in public schools in each school district in the country. Second, a series of court cases and policy decisions at the federal level have restricted the powers of policymakers at all levels to combat contemporary educational segregation—both between districts and between schools.

Residential patterns

Given the close linkage between school funding, socioeconomic composition of student bodies, and housing choices in the United States, one of the leading causes of school segregation is housing segregation. Residential segregation has been persistent throughout U.S. history and increased particularly during the Jim Crow era in the South in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Segregation spiked again in the 1960s across the country, as many white families chose to avoid court-mandated desegregation by moving to whiter jurisdictions.13

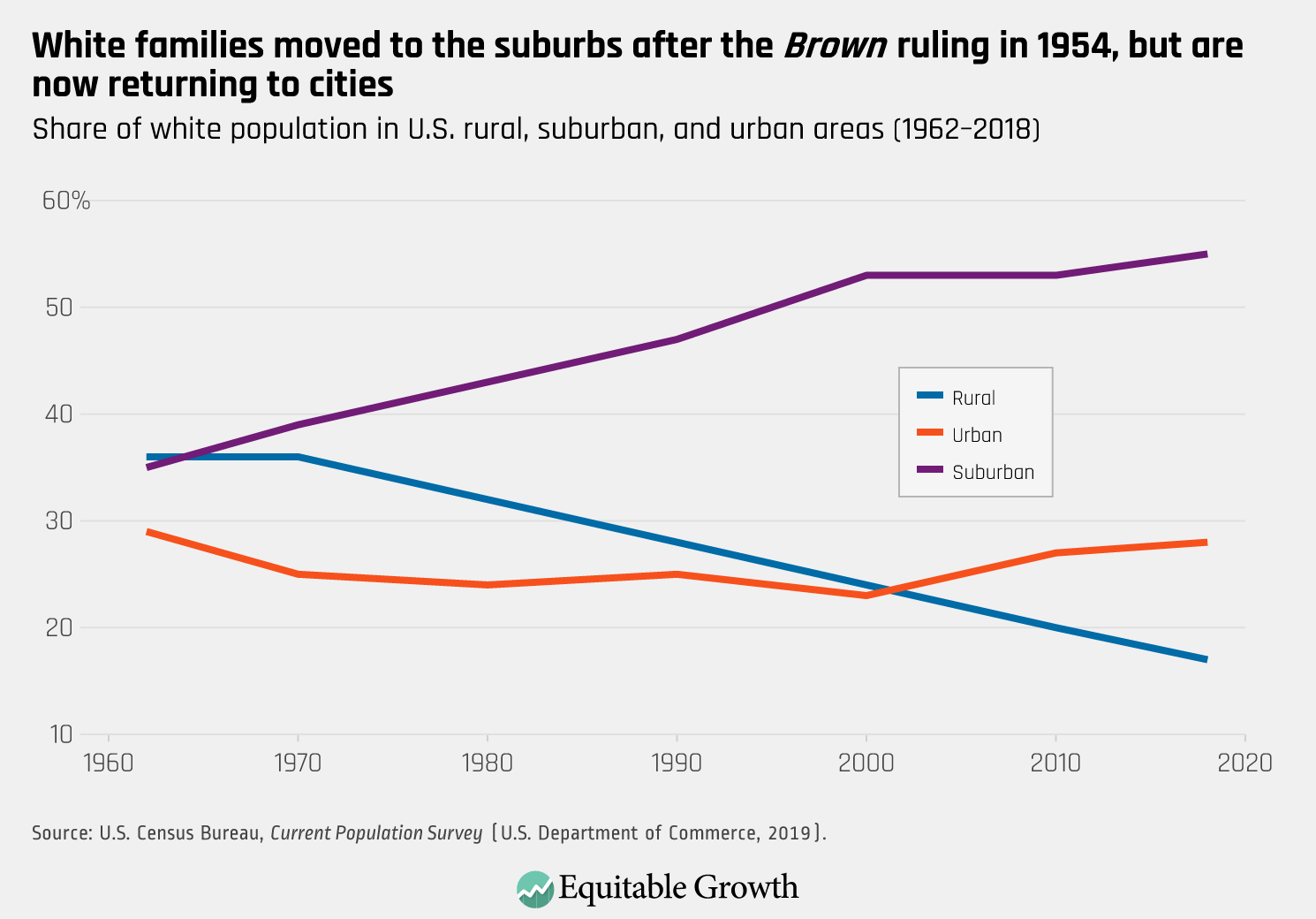

Beyond individual choices, Richard Rothstein at the Economic Policy Institute and other scholars detail the ways in which public policies at all levels—including discriminatory zoning, taxation, subsidies, and explicit redlining—work in concert with private actions to shut black families out of white neighborhoods and entrench segregation.14 Together, this process of residential exclusion and “white flight” to the suburbs was profound. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

Income-based segregation has also risen in recent decades, worsening white flight and creating socioeconomic divides between neighborhoods for families of all races. Among other scholars, Equitable Growth grantee and Stanford University sociologist Sean Reardon and Cornell University sociologist Kendra Bischoff find that rising income inequality since 1970 has simultaneously driven increasing income-based segregation of affluent families of all races away from lower- and middle-income families.15 Ann Owens of the University of Southern California argues that rising inequality worsened the cycle of housing and school segregation by income, as high-income families have become concentrated in districts where they can hoard resources and provide their children an advantage in the increasingly competitive and unequal economy.16

Reardon and Bischoff’s data likewise demonstrate that low-income black families, in particular, are increasingly experiencing heightened levels of racial isolation, exacerbated by the clustering of affordable housing in low-income neighborhoods. Notwithstanding the growing role of income-based segregation, black and Hispanic families today are disproportionately concentrated, at all income levels, in segregated neighborhoods with fewer resources than predominantly white communities with similar income demographics.17

That said, residential patterns across racial groups have shifted notably in the 21st century. Indeed, sociologist and demographer William Frey at The Brookings Institution documents two important reversals of post-Brown white flight over the past 20 years. First, black and Hispanic families are increasingly moving to the suburbs. And second, white workers—especially young, college-educated professionals—are returning to cities.18 While these trends have mitigated racial residential segregation in many communities over the past two decades, income segregation has continued to rise for all racial groups over the same period.19

Legal scholar Will Stancil at the University of Minnesota Law School’s Institute on Metropolitan Opportunity points to several examples where this kind of diversification within the suburbs—backed by mobilization of a diverse coalition and policy changes such as those described below—has paved the way for new local efforts pushing desegregation in those communities.20 Progress on integration has also taken place in recent years in small towns that have received a large number of recent Hispanic immigrants.21 Other scholars point to similar possibilities in newly diverse city centers.22 Nevertheless, the most recent evidence indicates that schools in both the suburbs, small towns, and cities will remain highly segregated in the absence of public policies that encourage, enforce, and maintain integration.23

Policies driving sorting by race and income

As the Supreme Court ruled in the Green case, durable solutions to segregation must go beyond technically opening all schools to all students under “freedom of choice” plans and must also include effective reforms by school districts to cultivate racial and income diversity across schools.24 In the absence of such systems, substantial evidence shows that sorting of students by race and income across schools is inevitable.25 While sorting between districts occurs when families change their residences or gerrymander school-district boundaries around their place of residence, sorting between schools in the same district is also very common. In recent decades, a variety of economic trends and policy reforms have driven increased racial and socioeconomic sorting of students and therefore worsened segregation across schools.

Opting out of public education altogether has been one option that has increased race- and income-based segregation in many communities. While moving to predominantly white suburbs was a more common response, empirical evidence from economists Charles T. Clotfelter of Duke University, Nathaniel Baum-Snow of Brown University, and Byron Lutz of the Federal Reserve confirms that many white families in both the North and South increasingly enrolled their children in private schools to sidestep desegregation.26 Equitable Growth grantee and newly appointed University of California, Berkeley economics and public policy professor Ellora Derenoncourt finds that the increase in private-school enrollment in northern cities began even earlier and was partially a response to the arrival of black migrants during the Great Migration of blacks from the agrarian South to the industrialized North in the first half of the 20th century as well.27 Today, private schools are 69 percent white (compared to 49 percent white for public schools) and account for approximately 16 percent of metropolitan-area school segregation.28

Charter and magnet schools can have a similar effect on segregation by creating parallel systems within public school districts, theoretically open to all but in practice facilitating race- and income-based sorting.29 A positive element of both charter and magnet schools is their districtwide or larger attendance zones. This feature has the potential to overcome the ways in which school attendance zones, such as school-district boundaries, can reproduce in schools the patterns of residential segregation that exist in neighborhoods.30 There are, however, important differences between the two categories of schools. Magnet schools are administrated by school districts and may have open or selective admissions policies, and are funded by the federal government as vehicles for integration, whereas charter schools are privately administered, compete for students, and often set many of their own admissions criteria.31

In the cases of both charter and selective magnet schools, inconsistent and/or subjective student recruitment and admissions procedures—coupled with a lack of supervision—are risk factors for heightened levels of segregation. As with school attendance zones, the admissions procedures at charter and selective magnet schools are not explicitly discriminatory yet often still result in substantial segregation, given racial and socioeconomic resource disparities.32 Specifically, the advantages enjoyed by wealthier, largely white families in the form of time, information, and money often gives their children a significant leg-up in identifying and securing a place in the best charter and selective magnet schools.33 In addition to their admissions policies, other scholars argue that strict discipline practices at charter schools push out low-income and minority students and artificially inflate test scores for the more advantaged students left behind.34

In many places, the result is heightened segregation both between charters and traditional schools and among charter schools themselves.35 Indeed, whereas only 4 percent of traditional public schools have 99 percent minority enrollment, that figure is 400 percent greater for charter schools, at 17 percent.36 Unsurprisingly, these dynamics are worse in the case of voucher schools—traditional private schools that receive public funding yet receive even less oversight than charter schools in terms of civil rights and other educational standards.37

The flip side is this: Despite enrolling more students and producing more consistent results in integrating schools and improving outcomes, magnet schools currently receive four times less federal funding than charter schools.38 This disparity in federal funding is a particularly startling trend, given that charter funding goes to private and, in some cases, for-profit organizations—often with limited oversight—as interdisciplinary scholar Noliwe Rooks at Cornell University critiques.39

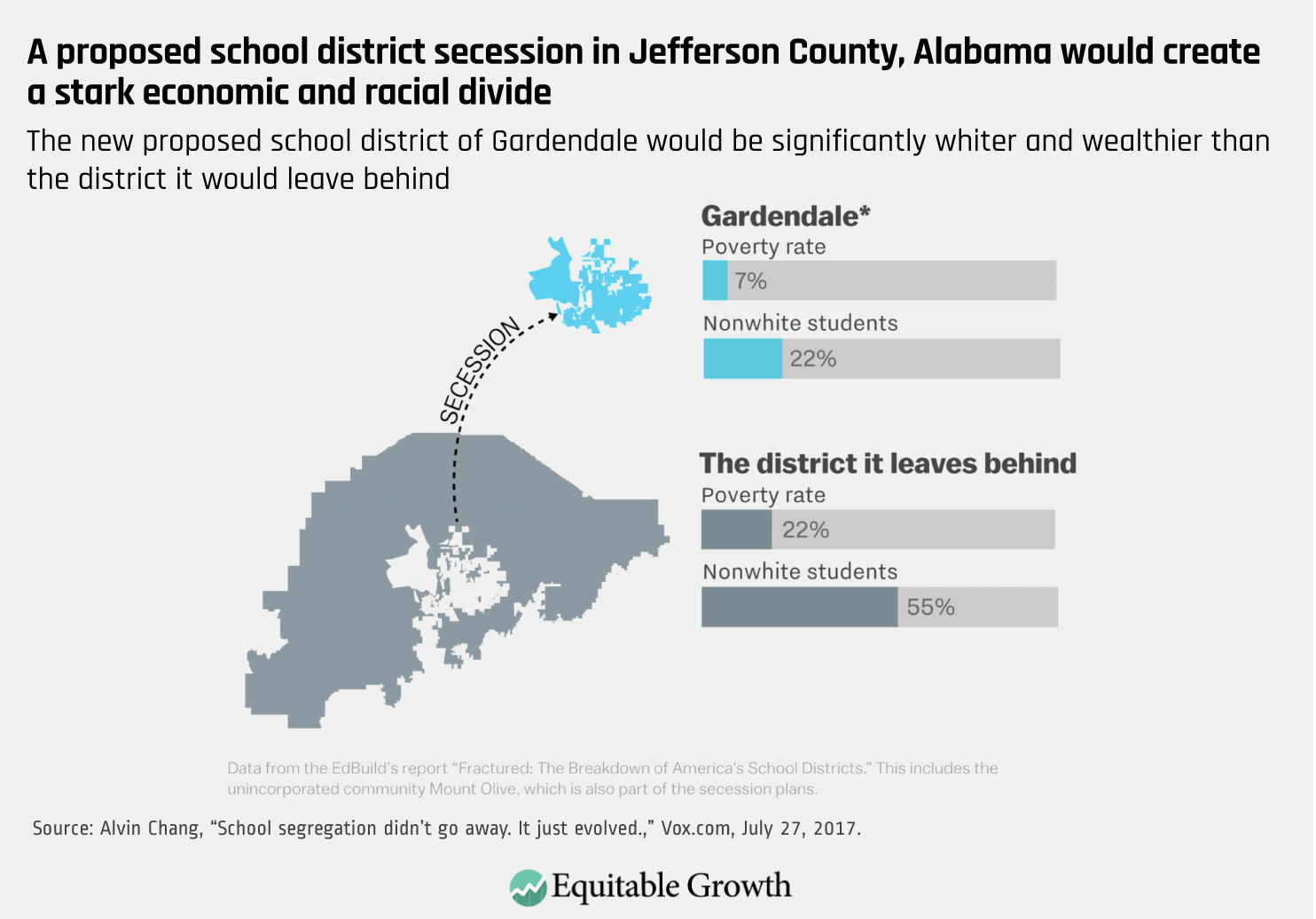

The gerrymandering of public school districts via secession also is becoming increasingly common. Instead of moving or enrolling their children in private or specialized public schools, many wealthy, largely white families have opted out of integrated schools by supporting the secession of their neighborhoods from a larger school district to create their own gerrymandered school districts. As New York Times magazine journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones illustrates in the case of Jefferson County (where Birmingham, Alabama is located), this strategy has roots in the early efforts to resist court-ordered desegregation in the 1960s but is becoming more frequent in the 21st century.40

Importantly, as highlighted in UC Berkeley economist and public policy professor Rucker Johnson and Newsweek reporter Alexander Nazaryan’s new book, Children of the Dream: Why School Integration Works, in cities such as Charlotte, Birmingham, and Memphis, these secessions can have big impacts on school funding disparities, given that 45 percent of schools’ budgets come from local property taxes in the United States.41 As a result, high-income families that secede from their school districts drain funding and worsen segregation for the low-income and middle-class children left behind.42 The proposed secession of Gardendale, Alabama from Jefferson County, for example, would increase levels of poverty and segregation in the original district. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

Declining civil rights enforcement

In the context of the changes in housing patterns and school enrollments, shifts in the legal system’s approach to segregation to at the federal level since the 1970s limited the ability of policymakers at all levels to push against these headwinds. Despite frequent claims that busing failed, there is a consensus among most researchers that the legal system played an important role in the early decline in school segregation after Brown, especially in the 1970s and 1980s.43 While it is true that opponents of integration emphasized the image of forced busing to drum up resistance to desegregation plans, the evidence is clear that these plans (whether or not they included busing) were effective in reducing segregation.44

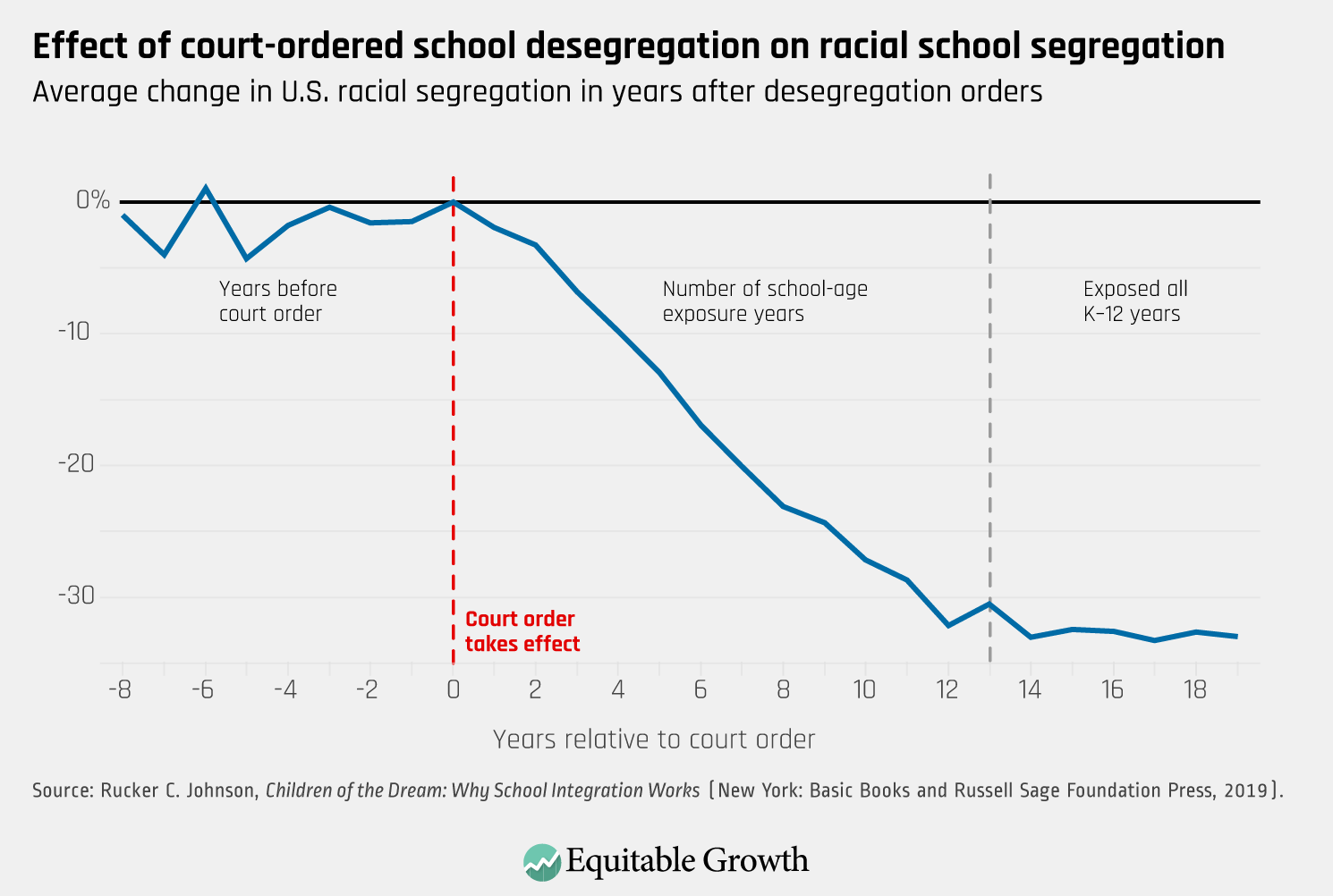

UC Berkley’s Johnson finds dramatic declines in black-white segregation in response to desegregation plans mandated by federal courts in the late 1960s through late 1980s, and there is even evidence that this legal momentum spilled over to reduce segregation in other communities as well.45 The executive branch played an important role in this period too, initiating cases against segregated districts and threatening to cut federal funding for districts that flouted integration plans. (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6

Despite the success of these early desegregation orders at reducing segregation, a series of subsequent U.S. Supreme Court decisions and changes in federal administrative priorities limited the frequency and scope of federal desegregation orders. While other cases had notable impacts, the three most relevant to the discussion here are Milliken v. Bradley, which prohibited federally mandated desegregation plans across school districts to reduce segregation in 1974; Board of Education of Oklahoma City v. Dowell, which authorized in 1991 the dissolution of desegregation orders, even when doing so would increase de facto segregation; and Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1, which restricted the use of race in voluntary student assignment plans aiming to reduce between-school segregation.46 These three court decisions coincided with important inflection points, when desegregation began to slow down before eventually reversing with the onset of the 1990s, particularly in the South. (See Figure 7).

Figure 7

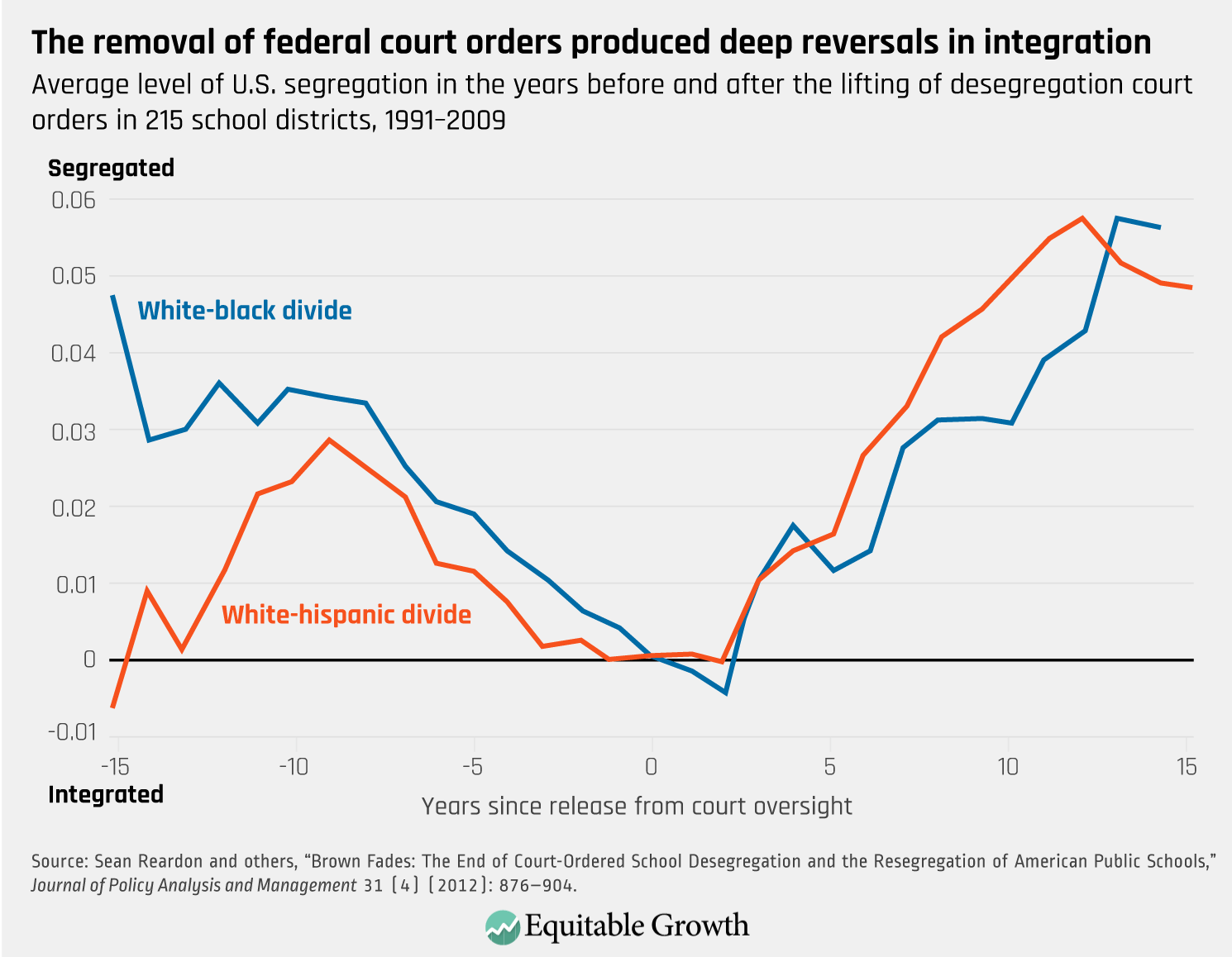

In lockstep with these judicial changes, the executive branch, starting in the late 1980s, began to defund and deprioritize desegregation enforcement, further reducing the quantity of enforcement actions and resultant court orders.47 There is strong microeconomic evidence that this reduction in legal enforcement of segregation was critical in driving resegregation. Indeed, in the two decades following the Dowell decision, the lowered standard for maintaining court oversight, coupled with changes in federal priorities, resulted in the release of 215 school districts from court oversight—45 percent of the 483 districts that had been subject to desegregation orders in 1990.48 The consequence of these changes was a steep rise in segregation, lasting for at least 15 years in districts where federal court orders were lifted. (See Figure 8.)

Figure 8

Effects of school segregation on inequality, mobility, and growth

Empirical studies in recent decades shed new light on the different ways that racial and socioeconomic school segregation can perpetuate both racial and economic inequality, in addition to impeding economic mobility and ultimately dampening overall U.S. economic growth. School segregation’s effects on economic inequality are numerous—exacerbating local school district funding disparities, resulting in lower curricular quality, cultivating discriminatory stereotypes, and stratifying social networks. In turn, these disparities dampen disadvantaged children’s academic performance, future labor market opportunities, and other social outcomes critical to their prospects for economic mobility.

In terms of growth, school segregation deteriorates the human capital base of the country by depriving millions of U.S. students of a quality education and thereby depressing aggregate levels of innovation and productivity growth in our economy. Additionally, the intergroup divisions and inequalities created by segregation corrode the social capital, or generalized trust, upon which the free exchange of goods, services, and ideas—and thus the efficient functioning of markets—rely.

School segregation and economic inequality

In the decades following the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown, economic and other social scientific research substantiated the decision’s key finding that separate schools are inherently unequal—in terms of school resources, learning opportunities, curricular quality, stereotypes, access to social networks, and academic performance.49 As the NAACP observed in the lead-up to Brown, segregated schools were never equally funded.50 Since school education funding is tied to property tax revenue in the surrounding communities and higher-income families tend to move to neighborhoods with whiter, wealthier schools, low-income and majority-minority schools usually suffer from chronic underfunding.51

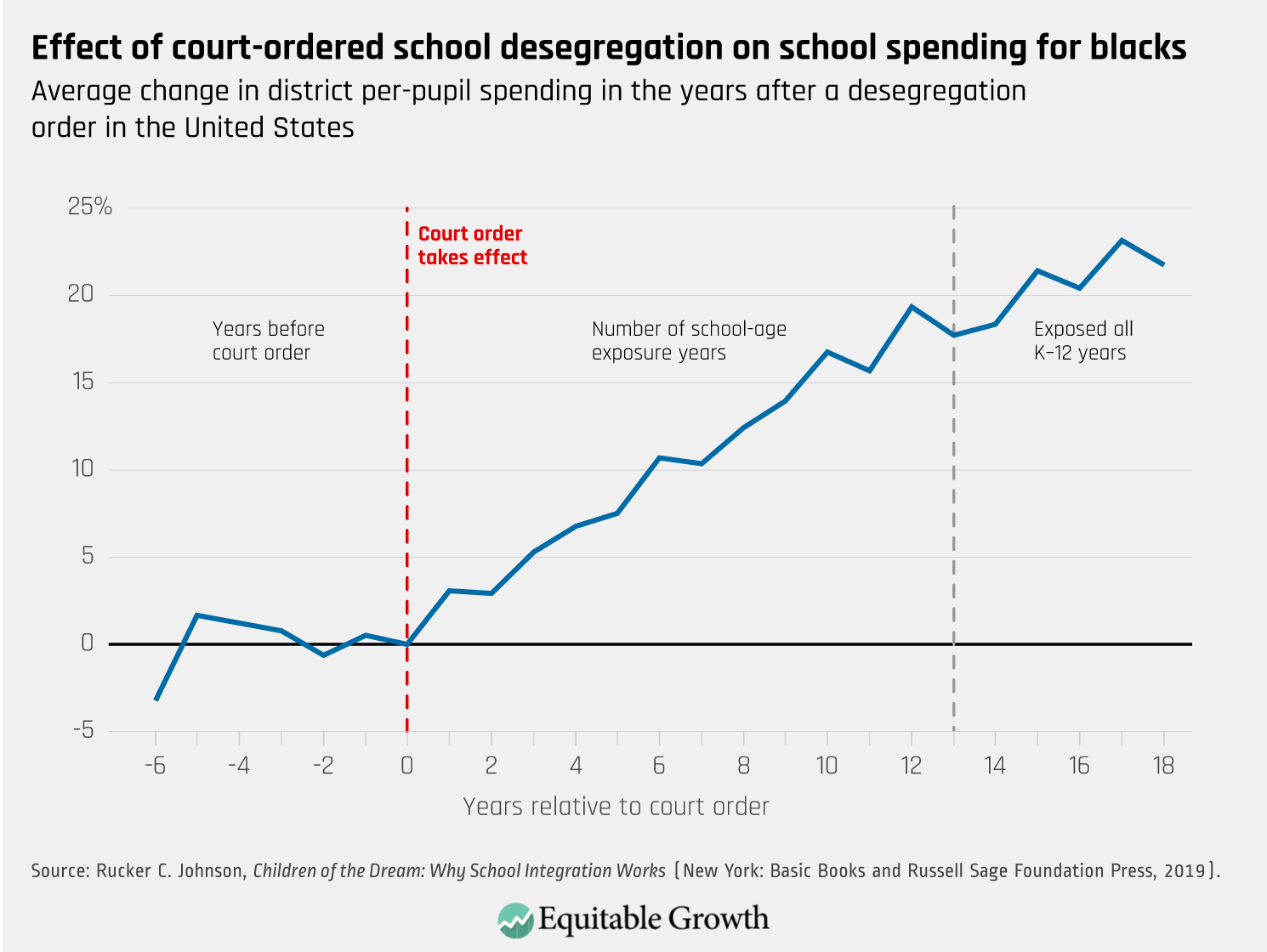

The early wave of desegregation made significant progress in closing this disparity in the average school funding available for black and white students. Using a detailed dataset on school integration orders, UC Berkeley’s Johnson’s finds large positive effects of court-ordered desegregation during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s on per-pupil education spending for black students. As in the other figures from Johnson’s book, Children of the Dream, this analysis tracks the average effects on funding across the hundreds of school districts that were subject to desegregation orders over this period. (See Figure 9.)

Figure 9

Conversely, with the decline of integration in recent decades, disparities between majority-white and majority-minority school districts have persisted. Today, in the aggregate, predominantly white districts in the United States receive an estimated $23 billion more in funding per year compared to predominantly nonwhite districts, despite serving the same number of students, according to EdBuild, a nonprofit research and advocacy organization focused on improving how states fund their schools.52

On top of financial resources, UC Berkeley economist Johnson, along with Susan Eaton at Brandeis University and C. Kirabo Jackson at Northwestern University, demonstrate that school segregation limits access to smaller class sizes and higher-quality teachers, both of which are key conditions for academic growth and development.53 Given the chronic disinvestment in public schools in recent decades, the funding disparity today between segregated schools is further entrenched by the reliance of many schools on parents’ disposable time and money for fundraising—as is the case for many charter schools.54

These large funding disparities have clear implications for academic and economic disparities. Specifically, studies by Jackson, Johnson, and Claudia Persico at American University—and by economists Jesse Rothstein and Julien Lafortune at UC Berkeley and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach at Northwestern—independently demonstrate that increasing school funding has a direct effect on improving academic outcomes.55 Despite debate in older research, Jackson reviews the literature on the topic and concludes that these more-recent studies are just two prominent examples of a recent series of empirical papers using more rigorous quasi-experimental methods to substantiate a strong causal relationship between school spending and student outcomes.56

School segregation also reinforces intergroup biases and stereotypes with negative implications for children’s opportunities and social cohesion in the U.S. economy as a whole. Segregation—whether along the lines of race, class, or some other characteristic—by definition makes this characteristic more salient for children as a means for separating in-groups from out-groups. In other words, when students are segregated by race, it sends a message that members of the other racial group are fundamentally different and deserving of different opportunities.57

Additionally, the homogenous environments created by school segregation inevitably foster racial biases and stereotypes about underrepresented groups. The late psychologist Gordon Allport’s widely validated contact hypothesis demonstrates that intergroup contact is necessary for overcoming intergroup distrust and disproving unfounded stereotypes.58 Yet segregation today entails low levels of exposure, especially for white students, to members of other ethnic and socioeconomic groups. This lack of exposure increases the prevalence of racial biases by limiting opportunities for the out-group to challenge or disprove these discriminatory clichés.59 (See Figure 10.)

Figure 10

This lack of intergroup exposure also generates racial and income-based inequality in access to social networks, which are important tools for children to develop their professional aspirations and to eventually obtain labor market opportunities. For low-income and minority students, lack of exposure to children whose parents have a wide array of incomes, backgrounds, and professions can cause these disadvantaged students to internalize that certain educational and professional opportunities are not available to them.60 Students in segregated schools do not just lose out on having diverse peers but also are far less likely to be exposed to a diverse pool of teachers—critical role models for developing children’s skills, ambitions, and interests.61

Conversely, recent research shows that exposure to a diversity of role models can inspire children to pursue careers they otherwise would not have considered. Equitable Growth grantee and Harvard University doctoral student Alex Bell, former Equitable Growth Steering Committee member and Harvard economist Raj Chetty, and their co-authors, for example, find that exposure to innovation during childhood is a key determinant of who becomes an inventor and that lack of exposure holds back the careers of many low-income and minority children who otherwise would have become inventors.62

Beyond these role model effects, social networks often play an even more concrete role in connecting students to educational and economic opportunities. When children begin applying to colleges and for job opportunities, for example, extensive and varied social networks provide critical information and references for successfully securing these new opportunities.63

School segregation and economic mobility

Numerous empirical studies show that the segregation of U.S. public schools results in large disparities in outcomes that limit children’s opportunities for economic and social mobility throughout their educational and professional careers. The impact of segregation on economic outcomes is first evident in schools, causing large academic disparities between children of different racial and socioeconomic backgrounds.64 There are debates over the mechanisms driving this effect, but there is a consensus among empirical scholars that income and racial segregation have a negative impact on the academic achievement of poor and minority students.65

While these effects are concentrated among low-income students of color, economists Stephen B. Billings at the University of Colorado, David J. Deming at the Harvard Kennedy School of Public Policy, and Jonah Rockoff at Columbia University find that the end of desegregation via busing in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg schools, in North Carolina’s biggest metropolis, reduced test scores and high school graduation rates for both white and black students who ended up in newly segregated, high-poverty schools.66

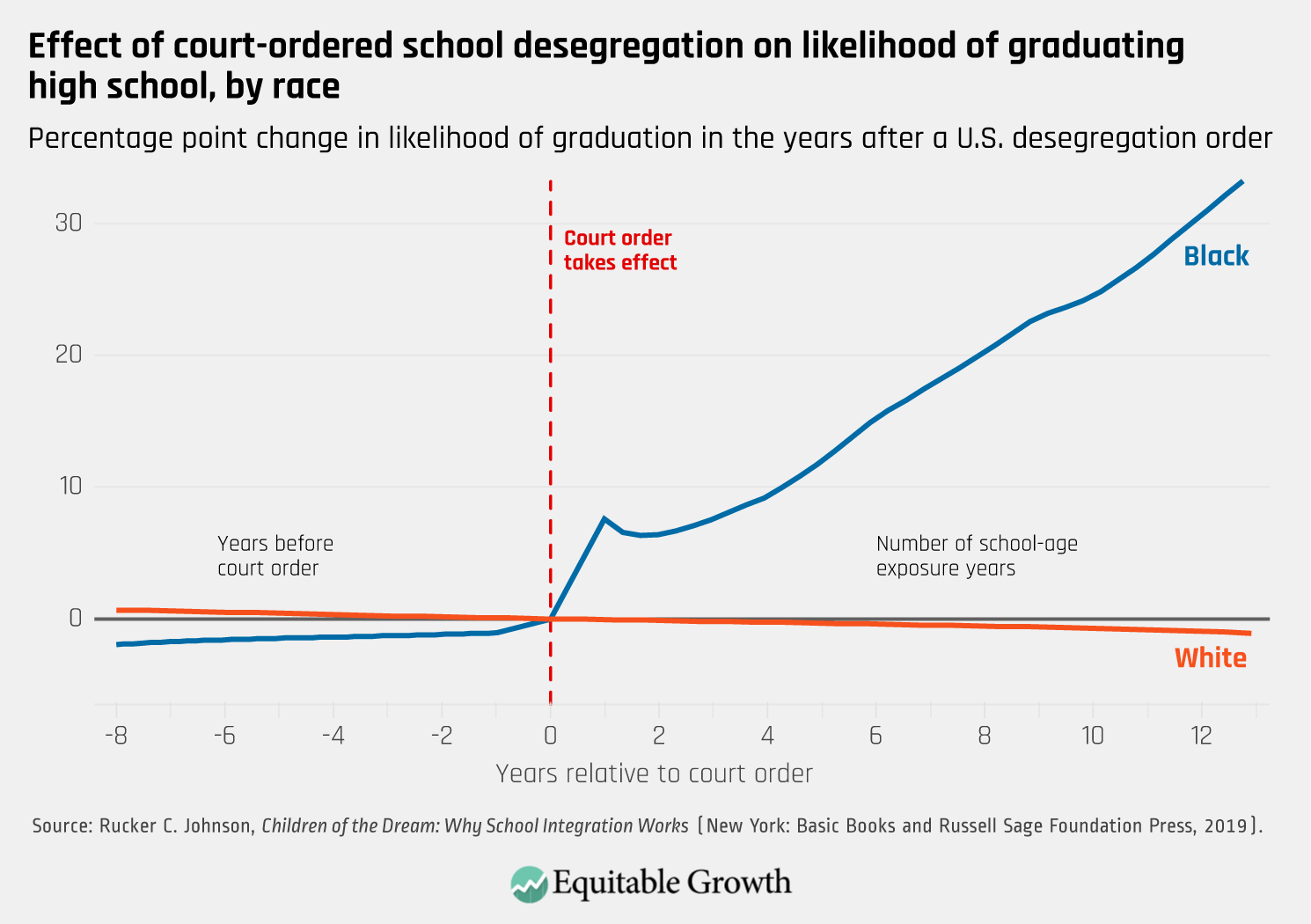

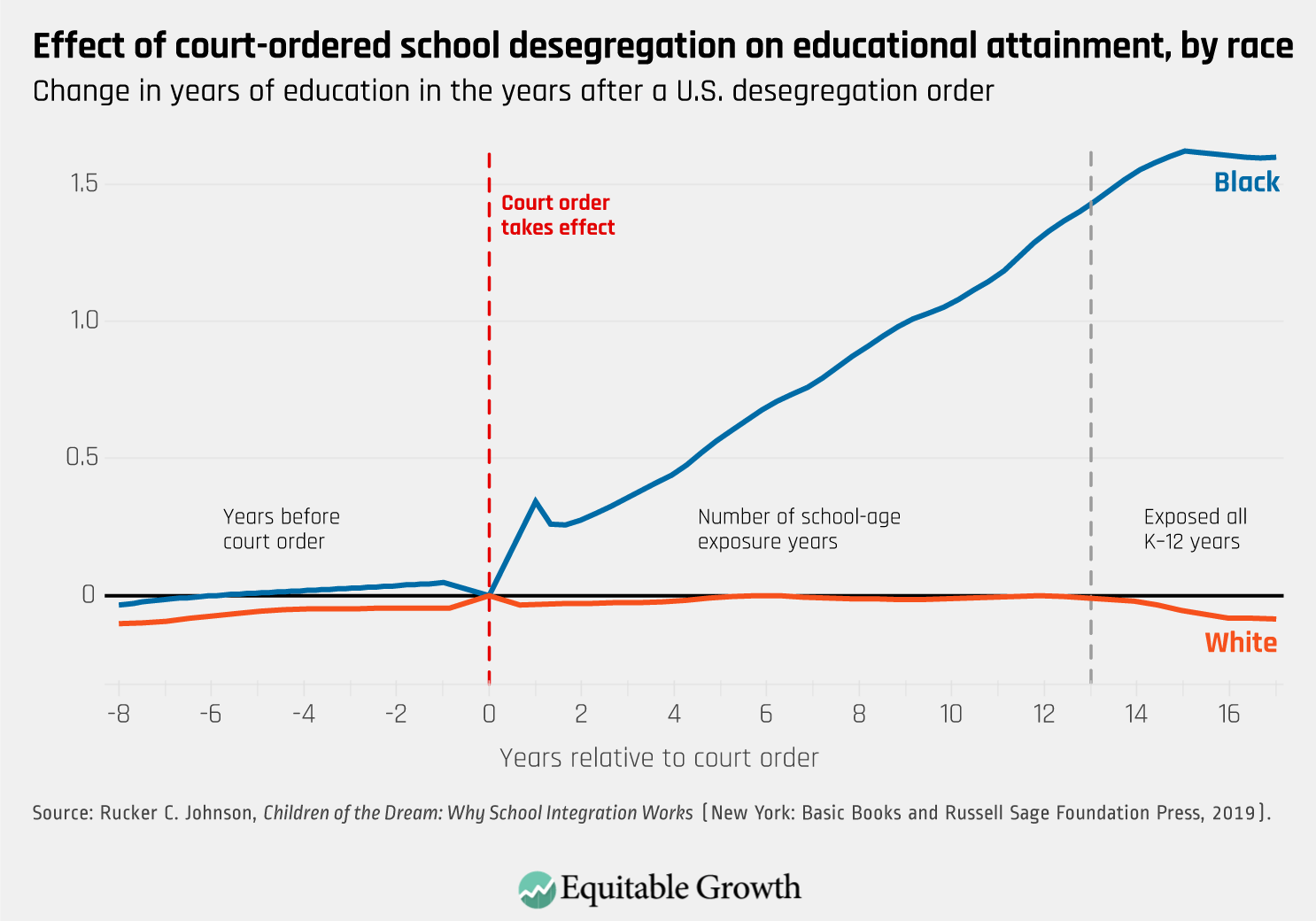

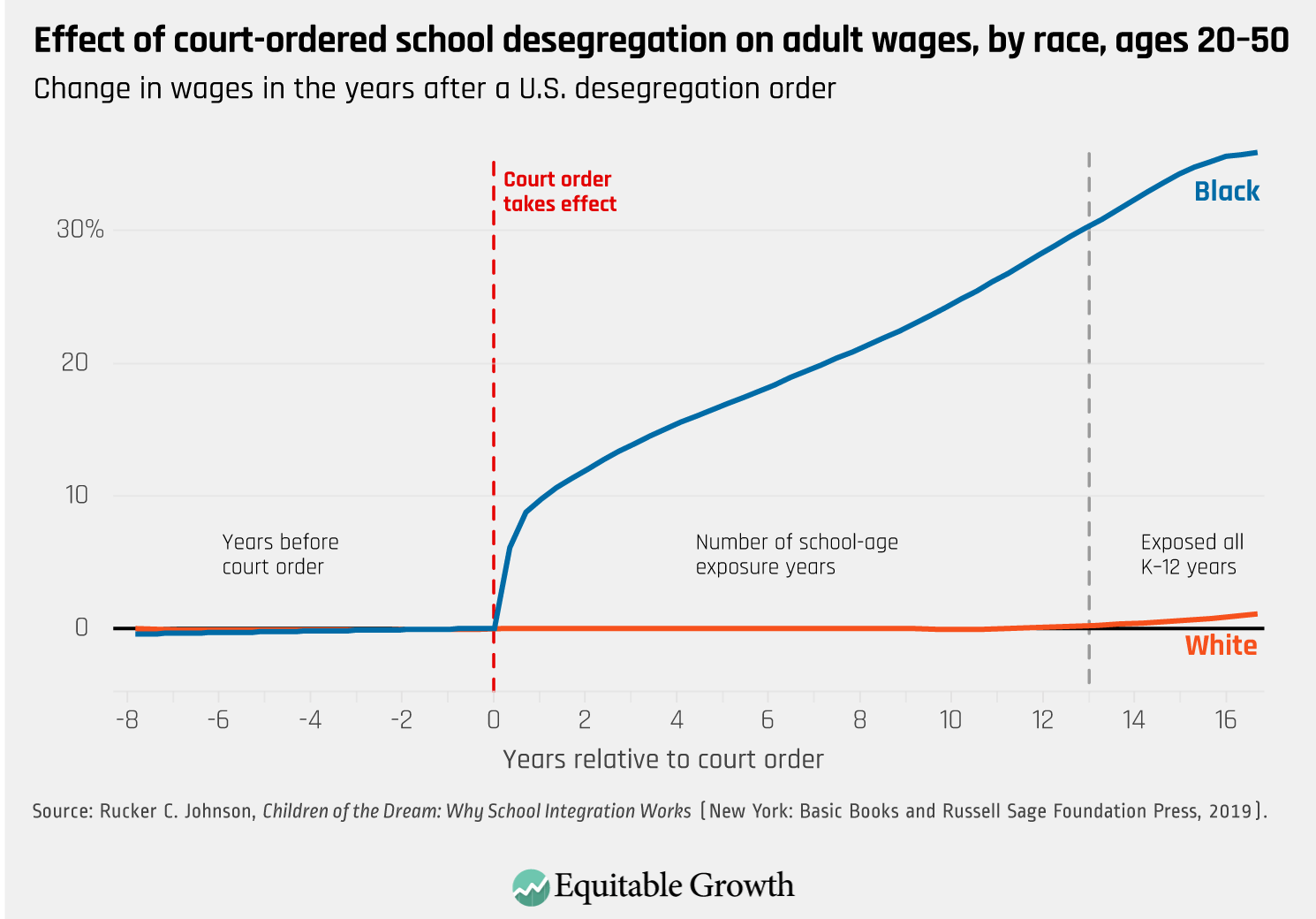

Conversely, desegregation produces large improvements in a variety of academic outcomes for economically and racially marginalized students without lowering the performance of their more advantaged classmates. UC Berkeley’s Johnson estimates that black students in desegregated schools throughout their Kindergarten through 12th grade education stayed in secondary school for one additional year and had a 30 percentage point greater likelihood of graduation than their peers in segregated schools. (See Figure 11 a-b.)

Figure 11 a

Figure 11 b

Given these gains, it is unsurprising that Johnson likewise finds substantial increases in college attendance and completion for black students who were students in newly integrated schools. Johnson’s analyses also validate the idea that the benefits of integration for blacks did not come at the expense of white students. Instead, he shows no negative impacts on whites’ educational and economic attainments resulting from desegregation.67

For many low-income and minority students, the effects of educational segregation are durable over the long term, influencing higher education, earnings, and other adult outcomes and thereby restricting their economic mobility prospects. Racial and income-based segregation, respectively, reduce the likelihood that minority and working-class students will attend college.68 Segregation increases disadvantaged students’ future risk of poverty and unemployment, and it depresses their earnings throughout their careers.69 Finally, segregation leads to subsequent increases in the likelihood of criminal involvement for students of all races isolated in high-poverty schools, and it likewise increases chronic health problems in adulthood for children from low-income, minority communities.70

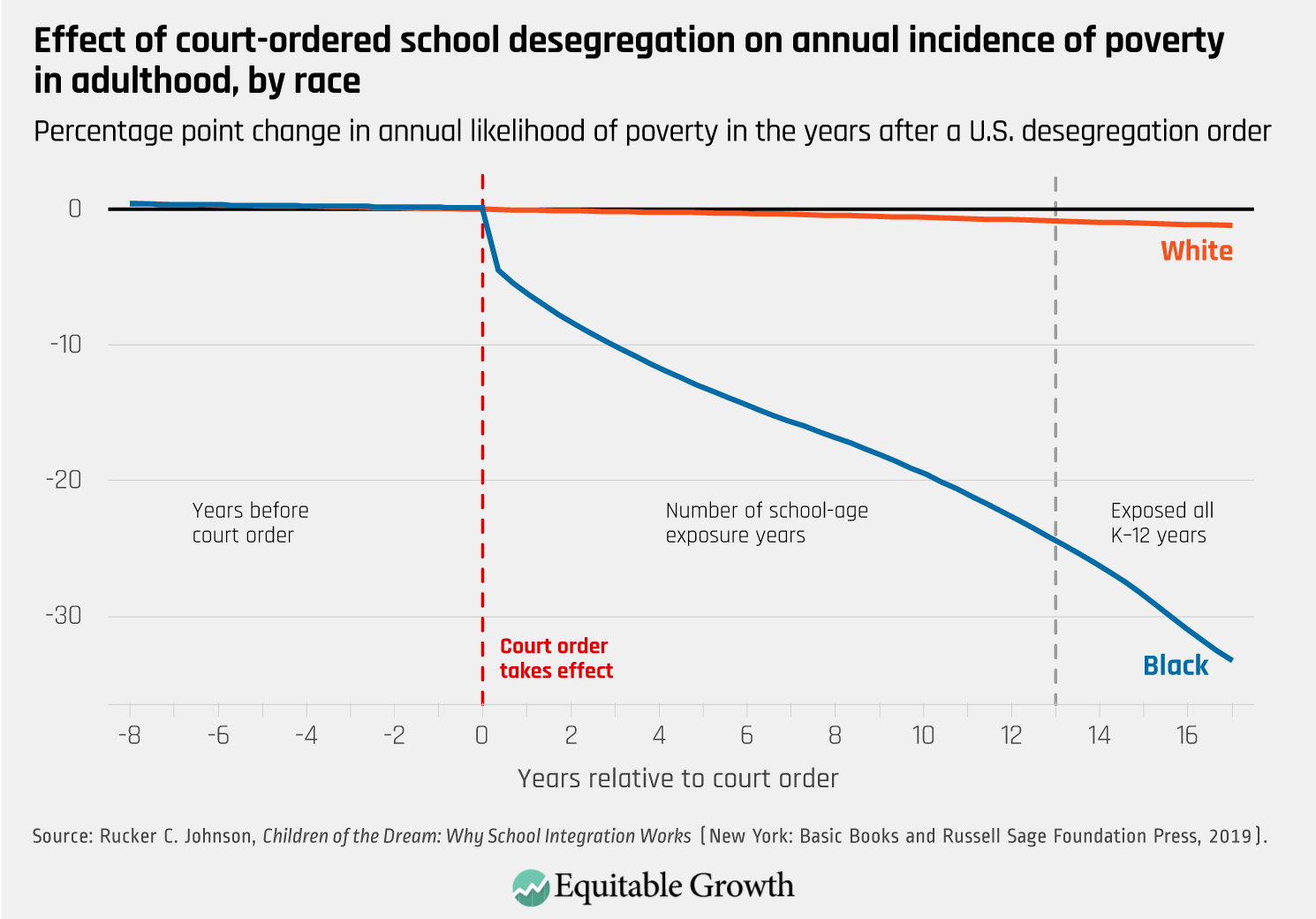

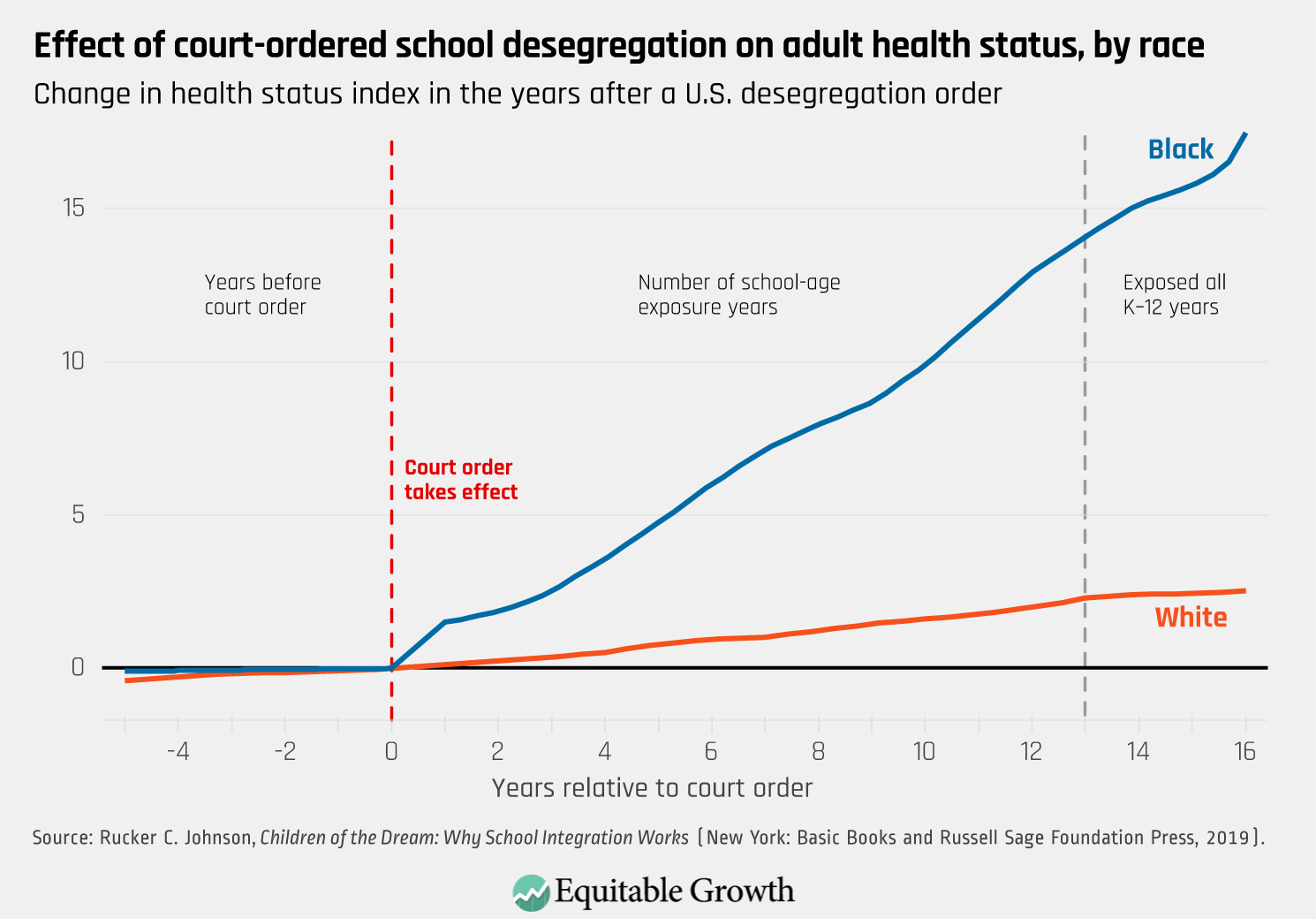

Illustrating several of these long-term impacts, UC Berkeley’s Johnson calculates the effects of desegregation on adult outcomes. In particular, for blacks, he finds the average effects of a 5-year exposure to court-ordered school desegregation led to about a 15 percent increase in wages, an 11 percentage point decline in the annual incidence of poverty, and a substantial boost to health status in adulthood. Similarly, exposure to desegregation beginning in the elementary school years produced a 3 percentage point reduction in the annual incidence of incarceration and a 22 percentage point decline in the probability of adult incarceration for black students. (See Figure 12 a-c.)

Figure 12 a

Figure 12 b

Figure 12 c

In addition to its independent effects, school segregation also damages low-income and disadvantaged students’ prospects for economic mobility by reinforcing residential segregation. Indeed, a variety of empirical studies confirm that upper-income and white families choose to live near schools with more upper-income and/or white students.71 These families’ choices are based on the implicit or explicit assumption that demographics are a proxy for school quality—despite significant evidence that economically advantaged students have high chances of success regardless of the demographics of their schools.72 The combined result of these individual choices is a retrenchment in the cycle of housing segregation, school segregation, funding inequalities, and academic disparities.

Pointing to the tight links between residential and educational segregation, Harvard’s Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren, along with their co-authors, find that poor children have the highest chances of economic mobility in neighborhoods with lower levels of residential segregation, greater social capital, and higher-quality public schools.73 Using these researchers’ data and a novel measure of residential segregation, Equitable Growth grantees and economists Trevon Logan (The Ohio State University), Marcus Casey (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign), Bradley Hardy (American University), and Rodney Andrews (University of Texas at Dallas) conclude that these effects can be durable intergenerationally as well. Indeed, they find that high levels of segregation as far back as the 19th century are correlated with notably lower contemporary economic mobility in many neighborhoods in the 21st century.74 These findings indicate that contemporary neighborhood and school segregation limit economic opportunities not just for students today, but also for their future children and grandchildren.

In related studies using mobility data assembled by Chetty and his co-authors, Yale University economist Barbara Biasi and UC Berkeley’s Johnson each estimate the impact of school funding on intergenerational mobility. Both economists both find that the equalization of school finance reforms implemented at the state level between 1986 and 2004 had a large positive effect on economic mobility—with low-income and minority students experiencing the largest benefits.75 In conjunction with the research above on educational segregation’s role in driving large income-and race-based resource disparities across schools, Biasi’s and Johnson’s studies provide strong suggestive evidence that significant progress toward integration would generate a strong boost in both school funding and intergenerational mobility for disadvantaged students.

School segregation and economic growth

On top of its effects on inequality and mobility, school segregation depresses aggregate human capital and social capital—two key drivers of social cohesion and economic growth. School segregation’s effects on human capital are clear: By abandoning millions of low-income and minority students in underfunded, underperforming schools, the U.S. economy is losing out on the talent and innovation necessary for a prosperous and dynamic economy.76

In the widely accepted human capital modification of Equitable Growth Steering Committee member and Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist and Nobel Laureate Robert Solow’s macroeconomic growth model, innovation and education are considered fundamental drivers of aggregate productivity and economic growth.77 Providing empirical confirmation of this relationship, research by Harvard economist Claudia Goldin and Equitable Growth Research Advisory Board member and fellow Harvard economist Lawrence Katz documents the central role of the expansion of primary and secondary education in driving aggregate productivity and output growth in the United States through the early 20th century.78

In light of this documented link, it is clear that by denying high-quality education to millions of students, school segregation today prevents the United States from reaping similar growth benefits from developing a more educated, and thus productive, workforce. Likewise, Alex Bell and his co-authors’ study on inventors, discussed above, as well as related work by Equitable Growth Research Advisory Board member and Michigan State economist Lisa Cook, also demonstrates that school segregation causes the U.S. economy to miss out on the “lost Einsteins” (and “Katherine Johnsons”) whose innovations could boost output and dynamism in the economy as a whole—were they not trapped in segregated schools.79

Due to the important role of social networks in connecting students to opportunities in higher education and labor markets, school segregation also is a notable driver of workplace segregation that disproportionately funnels low-income and minority students into lower-paying fields.80 University of Chicago economist Chang-Tai Hsieh and his co-authors estimate that 25 percent of the increase in aggregate output per worker between 1960 and 2010 was the product of improved allocation of talent due to the integration of women and ethnic minorities into numerous professions to which they had previously been denied access.81 By limiting the occupational opportunities of disadvantaged students, school segregation prevents this efficient allocation of talent, as well as the productivity gains derived from diverse workforces and teams.82

In addition to its effects in labor markets, many of the social ills that segregation causes down the line, including crime, poverty, and health problems, are obvious drags on the U.S. economy’s stock of talent as well. School segregation’s distortionary effects on human capital thus extend far beyond education to labor markets and society as a whole, further damaging the health and productivity of the economy.

Less present in policy debates yet equally relevant for a healthy economy is school segregation’s part in fomenting social distrust and thereby deteriorating social capital in communities across the country. In economics and other social sciences—especially in the work of French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, Harvard sociologist Robert Putnam, and Harvard economist Edward Glaeser—social capital is a term used to describe the network of social relationships that tie healthy communities together, as well as the interpersonal social trust formed by these bonds.83 Alternatively, social distrust, or the lack of social capital, is associated with arbitrary discrimination and missed opportunities for economic exchange and innovation across labor and consumer markets.84 By cultivating intergroup biases and stereotypes that foment distrust and division, school segregation thus contributes to inefficient markets and lost economic output.85 Research by Michigan State’s Cook also indicates that social capital is an important driver of innovation, pointing to another negative impact of segregation on the economy.86

On the macroeconomic level, low levels of social capital can deteriorate the institutions upon which human capital and growth rely. Harvard’s Goldin and Katz, for example, find that social capital was the key determinant of the early creation of universal, publicly funded secondary schools in Iowa and other states in the early 20th century.87 In contemporary times, empirical research by economists Alberto Alesina of Harvard and John Roemer of Yale, among other scholars, intricately explains the ways in which ethnic fractionalization, or distrust among different ethnic groups, drives underfunding of public goods, including public schools and other forms of public infrastructure, on both the federal and municipal levels in the United States.88 Given these effects on the microeconomic and macroeconomic levels, it is unsurprising that a variety of studies across the world have pointed to social capital as an important driver of economic growth.89

Supported by evidence from microeconomics, history, and political economy, Harvard political theorist Danielle Allen and University of Maryland, College Park political economist Eric Uslaner argue that segregation helps generate the contemporary distrust and division between ethnic groups in the United States by limiting opportunities for the contact necessary to form social trust, intergroup solidarity, and “political friendship.”90 By this account, it is segregation and bias, not diversity per se, which explain the underfunding of public schools and other public goods investigated in the work of Alesina, Roemer, and their respective co-authors.

Policy recommendations

School segregation is both a cause and a symptom of rising economic inequality in the United States. On the one hand, school segregation in recent decades increased with income inequality and income segregation. On the other hand, it worsened the situation and created even more severe inequalities in school funding, school quality, and adult economic opportunities for minority and low-income students. While these inequities have dramatic distortionary effects on the lives of individuals, they likewise deteriorate the human and social capital bases that fuel our economic engine. The good news, however, is that policymakers at all levels have at their disposal a variety of empirically tested strategies to achieve real integration for all students.

Reducing residential segregation is perhaps the most obvious method for reversing segregation in our public schools. To this end, cities across the country are experimenting with numerous policy reforms to create mixed-use, mixed-income neighborhoods that are home to a diverse array of families. These reforms notably include building affordable housing in upper- and middle-class neighborhoods, removing single-family zoning laws that exclude low-income and minority families, and setting minimum requirements for affordable units in new residential developments.91 School finance reforms at the federal, state, or metropolitan level that equalize funding across schools, such as those in Connecticut, New Jersey, or Wisconsin, also have the potential to lessen segregation and its impacts by decreasing the dramatic gaps in school funding—and thus quality—that currently drive housing patterns.92

In addition to fostering different residential trends, policymakers at all levels can reform the ways school-district and school attendance-zone boundaries transform residential segregation into educational segregation. Notably, consolidated school districts along county or metropolitan boundaries have been shown to be an extremely effective means of reducing segregation between urban and suburban communities, while also making cost savings possible due to returns to scale.93 Within school districts, there is growing evidence that redrawing or consolidating school attendance zones could likewise result in notable increases in integration without substantially increasing commute times for most students.94 Alternatively, many districts have successfully implemented intra- or interdistrict open enrollment policies that allow students to apply to attend schools outside of their school attendance zone or district.95 Other school systems have created magnet schools open to all students regardless of ZIP code.96

Such reforms, however, will have limited success in a vacuum. Numerous scholars argue that redistricting, open enrollment, and magnet school proposals should be implemented with student assignment systems that incorporate income and racial diversity as important objectives.97 Specific numerical requirements or objectives for children from various income backgrounds can be pursued without restriction to secure access to high-quality schools for low-income and middle-class students. While UC Berkeley’s Reardon, Equitable Growth grantee and Duke University economist William Darity, Jr., and others find that income-based integration does produce some racial integration, they argue racial diversity still needs to be incorporated as one of several important considerations in distributing students across schools.98

The key limitation of these plans is that race alone cannot be the determinative factor in placing a child in a particular school, as such a system is prohibited by the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1.99 Nevertheless, many school districts have leveraged modified plans that consider race and income with other factors to achieve significant increases in racial and socioeconomic integration, while minimizing commute times and ensuring students’ attend one of their top-choice schools.100 Successful models include recent efforts in Hartford, Connecticut, Eden Prairie, Minnesota, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Roaring Fork Valley, Colorado, and Dallas.101

It is particularly critical that these socioeconomic and racial diversity standards are applied to charter schools, which currently receive limited oversight in many states.102 While charter schools do face particularly severe levels of segregation, “diverse by design” charters provide clear evidence that integration of charter schools is indeed possible when backed by strong commitment from leadership and robust accountability mechanisms. As The Century Foundation researchers Halley Potter and Kimberly Quick argue, these efforts should be expanded from diverse-by-design schools to diverse-by-design systems, in which charters are incorporated into district and metropolitan plans to promote racially and socioeconomically equitable access to all public schools for all children.103

To reduce the prevalence of segregated education in desegregated schools, it is important for schools and school districts to ensure that all students in integrated schools, regardless of race or income, have access to a rigorous curriculum delivered by high-quality educators.104 Along with Equitable Growth grantee and Ohio State economist Darrick Hamilton, Brooklyn College professor Alan Aja, and other scholars, Duke’s Darity argues for moving from academic tracking systems with disparate impacts across race and class toward a system of providing gifted and talented education to all students.105 Preliminary evidence from a pilot study in this vein implemented between 2004 and 2009 by the state of North Carolina indicates that raising expectations and providing an excellent education to all students can improve outcomes across the board and increase the likelihood that low-income, minority students are subsequently identified as “gifted.”106

In his recently-published book, Children of the Dream, UC Berkeley’s Johnson presents evidence that these efforts to promote integration stand to have the greatest impact on student outcomes if implemented in conjunction with school finance reforms and the expansion of early childhood education.107 While integration and funding equalization respectively encourage the equitable redistribution of students and resources across schools, pre-Kindergarten programs funnel public funds to the most critical stage of child development and set the stage for all children to take advantage of the opportunities presented by integrated and well-funded public schools.

Although many of these policies are most applicable to state and local policymakers, the federal government can play a key role by providing funding, oversight, and incentives to encourage integration. Indeed, The Century Foundation’s Richard Kahlenberg, Halley Potter, and Kimberly Quick outline a robust role for the federal government—targeting federal funding for school and housing integration and increasing federal oversight over school district secessions, exclusionary zoning, and other local practices that foment segregation.108

Conclusion

A comprehensive effort to end school segregation in the 21st century must be grounded in a commitment to invest in and improve public schools across the United States, so these key educational institutions can provide skills and knowledge and build communities of learning and interaction for all children regardless of income or race.109 Such an effort would include increasing education funding and reducing class sizes, especially for the most disadvantaged schools. But it also would entail endowing public schools with unique curricular assets—from bilingual education to computer programming classes—to prepare students for the workplace of the future.110

In addition to improving outcomes for current students, these investments would encourage families of all ethnic and economic backgrounds to send their kids to public schools, opening up new possibilities for diverse districts and integrated schools.111

It is tempting to assume that school segregation is an unfortunate but unavoidable blemish in the U.S. educational system, but the research above makes clear that the opposite is true. School segregation is highly responsive to policy and legal changes, and integration boasts substantial benefits both for the most disadvantaged students and the U.S. economy as a whole.

In the 21st century, the economic competitiveness of the United States depends increasingly on our ability to innovate and upgrade aggregate productivity. By strengthening public-school system for all students, a renewed commitment to desegregation would not just improve outcomes for low-income students and students of color, but would also help secure a more innovative, productive, and vibrant economic future for the United States as a whole.

About the Author

Will McGrew is a research assistant at Princeton University, Texas A&M University, and the University of Utah, and a former research assistant at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. His primary research interests are education, labor markets, housing, public finance, political economy, law and economics, and microeconometrics. Prior to joining Equitable Growth, he worked as a research assistant at Yale Law School and the Yale Institution for Social and Policy Studies, and interned at Morgan Stanley Public Finance and the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. McGrew graduated from Yale University in 2018 with a bachelor’s degree in economics and political science. He is fluent in French and Spanish and proficient in Arabic.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Rucker Johnson, Marcus Casey, and Liz Hipple for their extensive feedback improving the research, argument, and writing in this issue brief, and to Ed Paisley, Dave Evans, Maria Monroe, Austin Clemens, and Emilie Openchowski for their contribution to the report’s editing, layout, and graphic design. The author also thanks the robust and growing group of scholars, journalists, and researchers upon whose work the report relies. Any and all errors are his own.

End Notes

1. Gary Orfield and others, “Brown at 60: Great Progress, a Long Retreat and an Uncertain Future” (Los Angeles: UCLA Civil Rights Project, 2014); Erica Frankenberg and others, “Harming our Common Future: America’s Segregated Schools 65 Years after Brown” (Los Angeles: UCLA Civil Rights Project, 2019).

2. Sean Reardon and Ann Owens, “60 Years After Brown: Trends and Consequences of School Segregation,” Annual Review of Sociology 40 (2014): 199–218.

3. Daniel Weinberg, John Iceland, and Erika Steinmetz, “Measurement of Segregation by the U.S. Bureau of the Census.” In Daniel Weinberg, John Iceland, and Erika Steinmetz, eds., Racial and Ethnic Residential Segregation in the United States: 1980-2000 (Washington: U.S. Census Bureau, 2002).

4. Orfield and others, “Brown at 60: Great Progress, a Long Retreat and an Uncertain Future.”

5. John R. Logan, Deidre Oakley, and Jacob Stowell, “School Segregation in Metropolitan Regions, 1970–2000: The Impacts of Policy Choices on Public Education,” American Journal of Sociology 113 (6) (2008): 1611–1644; Kori J. Stroub and Meredith P. Richards, “From Resegregation to Reintegration: Trends in the Racial/Ethnic Segregation of Metropolitan Public Schools, 1993–2009,” American Educational Research Journal 50 (3) (2013).

6. Stroub and Richards, “From Resegregation to Reintegration: Trends in the Racial/Ethnic Segregation of Metropolitan Public Schools, 1993–2009.”

7. Orfield and others, “Brown at 60: Great Progress, a Long Retreat and an Uncertain Future.”

8. Reardon and Owens, “60 Years After Brown: Trends and Consequences of School Segregation.”

9. Laura Meckler and Kate Rabinowitz, “The changing face of school integration,” The Washington Post, September 12, 2019; Kate Rabinowitz, Armand Emamdjomeh, and Laura Meckler, “How the nation’s growing racial diversity is changing our schools,” The Washington Post, September 12, 2019; Laura Meckler and Kate Rabinowitz, “How The Post’s analysis compares to other studies of school segregation,” The Washington Post, September 12, 2019.

10. Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman, “Distributional National Accounts: Methods and Estimates for the United States,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 133 (2) (2018): 553–609; Heather Boushey, Unbound: How Inequality Constricts Our Economy and What We Can Do About It (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019).

11. Ann Owens, Sean Reardon, and Christopher Jencks, “Income Segregation Between Schools and School Districts,” American Educational Research Journal 53 (4) (2016): 1159–1197.

12. Orfield and others, “Brown at 60: Great Progress, a Long Retreat and an Uncertain Future.”

13. Trevon D. Logan and John M. Parman, “The National Rise in Residential Segregation,” Journal of Economic History 77 (1) (2017): 127–170; John R. Logan, Weiwei Zhang, and Deirdre Oakley, “Court Orders, White Flight, and School District Segregation, 1970–2010,” Social Forces 95 (3) (2017): 1049–1075; Logan, Oakley, and Stowell, “School Segregation in Metropolitan Regions, 1970–2000: The Impacts of Policy Choices on Public Education”; David Harshbarger and Andre M. Perry, “The rise of black-majority cities: Migration patterns since 1970 created new majorities in U.S. cities” (Washington: The Brookings Institution, 2019); Leah Boustan, “School Desegregation and Urban Change: Evidence from City Boundaries,” American Journal of Applied Economics 4 (1) (2012): 85–108; Leah Boustan, “Was Postwar Suburbanization ‘White Flight’? Evidence from the Black Migration,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 125 (1) (2010): 417–443.

14. Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: Liverlight, 2017).

15. Sean F. Reardon and Kendra Bischoff, “Income Inequality and Income Segregation,” American Journal of Sociology 116 (4) (2011): 1092–1153. Alessandra Fogli and Veronica Guerrieri, “The End of the American Dream? Inequality and Segregation in US Cities.” Working Paper No. 26143 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2019).

16. Ann Owens, “Inequality in children’s contexts: The economic segregation of households with and without children,” American Sociological Review 81 (3) (2016): 549–574.

17. Stroub and Richards, “From Resegregation to Reintegration: Trends in the Racial/Ethnic Segregation of Metropolitan Public Schools, 1993–2009”; John R. Logan, “The Persistence of Segregation in the 21st Century Metropolis,” City Community 12 (2) (2013); Patrick Bayer and Robert McMillan, “Racial Sorting and Neighborhood Quality.” Working Paper No. 11813 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2005); Patrick Sharkey, Stuck in Place: Urban Neighborhoods and the End of Progress Toward Racial Equality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), p. 28; Marcus D. Casey and Bradley Hardy, “The Evolution of Black Neighborhoods Since Kerner,” RSF Journal of the Social Sciences 4 (6) (2018): 185–205; Andre M. Perry, Jonathan Rothwell, and David Harshbarger, “The devaluation of assets in black neighborhoods: the case of residential property” (Washington: The Brookings Institution, 2018).

18. William H. Frey, The Diversity Explosion: How New Racial Demographics are Remaking America (Washington: The Brookings Institution, 2018); J.R. Logan and B.J. Stults, “The persistence of segregation in the metropolis: New findings from the 2010 census” (Providence, RI: Russell Sage Foundation, 2011).

19. Kendra Bischoff and Sean Reardon, “Residential segregation by income, 1970–2009.” In J. R. Logan, ed., Diversity and disparities (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2014), pp. 208–233.

20. Will Stancil, “The White Suburbs That Fought Busing Aren’t So White Anymore,” The Atlantic, July 12, 2019; Kfir Mordechay and Jennifer Ayscue, “School Integration in Gentrifying Neighborhoods: Evidence from New York City” (Los Angeles: UCLA Civil Rights Project, March 2019).

21. Meckler and Rabinowitz, “The changing face of school integration.”

22. Kfir Mordechay and Jennifer Ayscue, “How Gentrification by Urban Millennials Improves Public School Diversity,” City Lab, July 8, 2019.

23. Nikole Hannah-Jones, “Choosing a School for My Daughter in a Segregated City,” The New York Times, June 9, 2016; Reed Jordan and Megan Gallagher, “Does School Choice Affect Gentrification” (Washington: Urban Institute, 2015); Kfir Mordechay and Jennifer Ayscue, “School Integration in Gentrifying Neighborhoods: Evidence from New York City” (Los Angeles: UCLA Civil Rights Project, 2019); Sarah Diem and others, “Diversity for Whom? Gentrification, Demographic Change, and the Politics of School Integration,” Educational Policy 33 (1) (2019).

24. Hannah-Jones, “Choosing a School for My Daughter in a Segregated City.”

25. Grover J. Whitehurst, “New evidence on school choice and racially segregated schools” (Washington: The Brookings Institution, 2017); Marc Stein, “Public School Choice and Racial Sorting: An Examination of Charter Schools in Indianapolis,” American Journal of Education 121 (4) (2015): 597–627.

26. Charles T. Clotfelter, “Private Schools, Segregation, and the Southern States,” Peabody Journal of Education 79 (2) (2004); Nathaniel Baum-Snow and Byron F. Lutz, “School Desegregation, School Choice and Changes in Residential Location Patterns by Race,” American Economic Review 101 (7) (2011): 3019–3046.

27. Ellora Derenoncourt, “Can you move to opportunity? Evidence from the Great Migration.” Working Paper (Harvard University, 2019).

28. Jongyeon Ee, Gary Orfield, and Jennifer Teitell, “Private Schools in American Education: A Small Sector Still Lagging in Diversity” (Los Angeles: UCLA Civil Rights Project, March 2018); Clotfelter, “Private Schools, Segregation, and the Southern States.”

29. Magnet schools are specialized public schools focused on particular skills or achievement levels, whereas charter schools are public schools run by private nonprofit—or, less frequently, for-profit—organizations.

30. In districts without open enrollment policies, school attendance zones demarcate which schools students are allowed to attend based on the location of their residence in the district. Tomas Monarrez, “Attendance Boundary Policy and the Segregation of Public Schools in the United States.” Working Paper (University of California, Berkeley, 2018); Genevieve Siegel-Hawley, Kimberly Bridges, and Thomas J. Shields, “Solidifying Segregation or Promoting Diversity?: School Closure and Rezoning in an Urban District,” Educational Administration Quarterly 53 (1) (2017): 107–141.

31. Richard D. Kahlenberg, Halley Potter, and Kimberly Quick, “A Bold Agenda for School Integration” (New York: The Century Foundation, 2019).

32. Robert Bifulco, Helen Ladd, and Stephen Ross, “Public school choice and integration evidence from Durham, North Carolina,” Social Science Research 38 (1) (2009): 71–85; Caterina Calsamiglia, Francisco Martinez-Mora, and Antonio Miralles, “Sorting in public school districts under the Boston Mechanism.” Working Paper No. 17/10 (University of Leicester, 2017); Jason Cook, “Race-Blind Admissions, School Segregation, and Student Outcomes: Evidence from Race-Blind Magnet School Lotteries.” Working Paper No. 11909 (Institute of Labor Economics, 2018).

33. Nihad Bunnar and Anna Ambrose, “Schools, choice and reputation: Local school markets and the distribution of symbolic capital in segregated cities,” Research in Comparative and International Education 11 (1) (2016): 34–51; Mark Schneider and others, “Networks to Nowhere: Segregation and Stratification in Networks of Information about Schools,” Midwest Political Science Association 41 (4) (1997): 1201–1223; Halley Potter and Kimberly Quick, “Holding Charter Schools Accountable for Segregation,” The Century Foundation Commentary blog, July 12, 2018; Erica Frankenberg, Genevieve Siegel-Hawley, and Jia Wang, “Choice Without Equity: Charter School Segregation and the Need for Civil Rights Standards” (Los Angeles: UCLA Civil Rights Project, 2010); Jarvis DeBerry, “How did schools known for their gatekeeping policies get designated ‘Equity Honorees’?” Times Picayune / NOLA.com, November 23, 2018; Times-Picayune Editorial Board, “New Orleans’ mission: Make schools truly equitable,” Times Picayune / NOLA.com, December 9, 2018; Gary Sernovitz, “What New Orleans Tells Us About the Perils of Putting Schools on the Free Market,” The New Yorker, July 30, 2018.

34. Emily Deruy, “Unequal Discipline at Charter Schools,” The Atlantic, March 18, 2016; George Joseph and CityLab, “Where Charter-School Suspensions Are Concentrated,” The Atlantic, September 16, 2016; Mónica Hernández, “The Effects of the New Orleans School Reforms on Exclusionary Discipline Practices” (New Orleans, LA: Educational Research Alliance, 2019).

35. Noliwe Rooks, Cutting School: Privatization, Segregation, and the End of Public Education (New York: The New Press, 2017); Emmanuel Felton, “Nearly 750 charter schools are whiter than the nearby district schools,” The Hechinger Report / NBCNews.com, June 17, 2018; Salvatore Saporito, “Private Choices, Public Consequences: Magnet School Choice and Segregation by Race and Poverty,” Social Problems 50 (2) (2003): 181–203; Jenn Ayscue and others, “Charters as a Driver of Resegregation” (Los Angeles: UCLA Civil Rights Project, 2018).

36. Ivan Moreno, “US charter schools put growing numbers in racial isolation,” Associated Press, December 3, 2017.

37. Ana Gazmuri, “School Segregation in the Presence of Student Sorting and Cream-Skimming: Evidence from a School Voucher Reform” (Toulouse: Toulouse School of Economics, 2017); Bayliss Fiddiman and Jessica Yin, “The Danger Private School Voucher Programs Pose to Civil Rights” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2019); Chris Ford, Stephenie Johnson, and Lisette Partelow, “The Racist Origins of Private School Vouchers” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2017); Mary Levy, “Washington, D.C. Voucher Program: Civil Rights Implications” (Los Angeles: UCLA Civil Rights Project, 2018).

38. Kahlenberg, Potter, and Quick, “A Bold Agenda for School Integration.”

39. Rooks, Cutting School: Privatization, Segregation, and the End of Public Education.

40. Nikole Hannah-Jones, “The Resegregation of Jefferson County,” The New York Times, September 6, 2017; EdBuild, “Fractured: The Breakdown of American’s School Districts” (2017); Erika W. Wilson, “The New School Segregation,” Cornell Law Review 102 (2016): 139–210; Mark Keierleber, “School District Secessions Are Accelerating, Furthering ‘State Sanctioned’ Segregation” (New York: The 74 Million, 2019).

41. Rucker C. Johnson, Children of the Dream: Why School Integration Works (New York: Basic Books and Russell Sage Foundation Press, 2019); “How much money does our school district receive from federal, state, and local sources?,” available at http://www.data-first.org/data/how-much-money-does-our-school-district-receive-from-federal-state-and-local-sources/ (last accessed September 26, 2019).

42. EdBuild, “Dismissed: America’s Most Divisive School District Borders” (2019).

43. Nikole Hannah-Jones, “It Was Never About Busing,” The New York Times, July 12, 2019.

44. Hannah-Jones, “It Was Never About Busing”; Johnson, Children of the Dream: Why School Integration Works.

45. Rucker Johnson, “Long-Run Impacts of School Desegregation and School Quality on Adult Attainments.” Working Paper 16664 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2011); Johnson, Children of the Dream: Why School Integration Works; Logan, Zhang, and Oakley, “Court Orders, White Flight, and School District Segregation, 1970–2010”; Elizabeth Cascio and others, “From Brown to busing,” Journal of Urban Economics 64 (2) (2008): 296–325.

46. Erwin Chemerinsky, “Making Schools More Separate and Unequal: Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1,” Michigan State Law Review 633 (2014): 633–646; Myron Orfield, “Milliken, Meredith, and Metropolitan Segregation,” UCLA Law Review 62 (2015): 364–462; Elizabeth Warren, “Busing-Supreme Court Restricts Equity Power of District Courts to Order Interschool Busing,” Rutgers Law Review (1975); U.S. Department of Education and U.S. Department of Justice, Guidance on the Voluntary Use of Race to Achieve Diversity and Avoid Racial Isolation in Elementary and Secondary Schools (2011); Michelle Adams, “Racial Inclusion, Exclusion and Segregation in Constitutional Law,” Constitutional Commentary 28 (2012): 1–35; Elissa Nadworny and Cory Turner, “This Supreme Court Case Made School District Lines a Tool for Segregation,” NPR, July 25, 2019.

47. Nikole Hannah-Jones, “Lack of Order: The Erosion of a Once-Great Force for Integration,” Pro Publica, May 1, 2014.

48. Sean Reardon and others, “Brown Fades: The End of Court-Ordered School Desegregation and the Resegregation of American Public Schools,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 31 (4) (2012): 876–904.

49. The Century Foundation, “The Benefits of Socioeconomically and Racially Integrated Classrooms” (2019).

50. Chris Hayes, “Investigating school segregation in 2018 with Nikole Hannah-Jones: podcast & transcript,” Why Is this Happening? blog, July 31, 2018; “Separate is Not Equal: Brown v. Board of Education: A Turning Point in 1950,” available at https://americanhistory.si.edu/brown/history/3-organized/turning-point.html (last accessed September 26, 2019).

51. Alvin Chang, “How segregation keeps poor students of color out of whiter, richer nearby districts,” Vox.com, July 25, 2019.

52. EdBuild, “Nonwhite school districts Get $23 billion less than white districts despite serving the same number of students” (2019).

53. Johnson, Children of the Dream: Why School Integration Works; Susan Eaton, The Children in Room E4: American Education On Trial (New York: Workman Publishing, 2007); Shino Tanikawa and Leonie Haimson, “Lower class size and school integration go hand in hand,” New York Daily News, May 17, 2019; C. Kirabo Jackson, “Student Demographics, Teacher Sorting, and Teacher Quality: Evidence from the End of School Desegregation,” Journal of Labor Economics 27 (2) (2009): 213–256.

54. Rooks, Cutting School: Privatization, Segregation, and the End of Public Education; Lisette Partelow and others, “Fixing Chronic Disinvestment in K-12 Schools” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2018); Linn Posey-Maddox, “Beyond the consumer: parents, privatization, and fundraising in US urban public schooling,” Journal of Education Policy 31 (2) (2016): 178–197; Michael Alison Chandler, “Some D.C. charter schools get millions in donations; others, almost nothing,” The Washington Post, August 26, 2015; Megan Batdorff and others, “Charter School Funding: Inequity Expands” (Fayetteville, AR: Department of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas, 2014); Laura McKenna, “How Rich Parents Can Exacerbate School Inequality,” The Atlantic, January 28, 2016.

55. C. Kirabo Jackson, Rucker C. Johnson, and Claudia Persico, “The Effects of School Spending on Educational & Economic Outcomes: Evidence from School Finance Reforms,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 131 (1) (2015): 157–218; Julien Lafortune, Jesse Rothstein, and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, “School Finance Reform and the Distribution of Student Achievement,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10 (2) (2018): 1–26; Christopher A. Neilson and Seth D. Zimmerman, “The effect of school construction on test scores, school enrollment, and home prices,” Journal of Public Economics 120 (2014): 18–31.

56. C. Kirabo Jackson, “Does School Spending Matter? The New Literature on an Old Question.” Working Paper No. 25368 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2018).

57. Ryan Enos and Christopher Celaya, “The Effect of Segregation on Intergroup Relations,” Journal of Experimental Political Science 5 (1) (2018): 26–38.

58. Gordon W. Allport, The Nature of Prejudice (New York: Basic Books, 1979); Amy Stuart Wells, Lauren Fox, and Diana Cordova-Cobo, “How Racially Diverse Schools and Classrooms Can Benefit All Students” (New York: The Century Foundation, 2016); James Laurence and others, “Prejudice, Contact, and Threat at the Diversity-Segregation Nexus: A Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Analysis of How Ethnic Out-Group Size and Segregation Interrelate for Inter-Group Relations,” Social Forces 97 (3) (2019): 1029–1066; Miles Hewstone and others, “Influence of segregation versus mixing: Intergroup contact and attitudes among White-British and Asian-British students in high schools in Oldham, England,” Theory and Research in Education 16 (2) (2018); Jeffrey C. Dixon and Michael S. Rosenbaum, “Nice to Know You? Testing Contact, Cultural, and Group Threat Theories of Anti‐Black and Anti‐Hispanic Stereotypes,” Social Science Quarterly 85 (2) (2004): 257–280.

59. Thomas F. Pettigrew and Linda R. Tropp, “A Meta-Analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90 (5) (2006): 751–783.

60. Jack Schneider, “The Urban-School Stigma,” The Atlantic, August 25, 2017.

61. Michael Hansen and Diana Quintero, “Teachers in the US are even more segregated than students,” The Brookings Institution blog, August 15, 2018.

62. Alex Bell and others, “Who Becomes an Inventor in America? The Importance of Exposure to Innovation.” Working Paper No. 24062 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2019).

63. Knowledge @ Wharton, “Why Social Networks Unwittingly Worsen Job Opportunities for Black Workers,” Management blog, May 10, 2013, available at http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/why-social-networks-unwittingly-worsen-job-opportunities-for-black-workers/.

64. David Card and Jesse Rothstein, “Racial segregation and the black-white test score gap,” Journal of Public Economics 91 (11-12) (2007): 2158–2184.

65. Ann Owens, “Income Segregation between School Districts and Inequality in Students’ Achievement,” Sociology of Education 91 (1) (2018); Peter Bergman, “The Risks and Benefits of School Integration for Participating Students: Evidence from a Randomized Desegregation Program.” Working Paper (Institute for the Study of Labor, 2018); Stephen B. Billings, David J. Deming, and Jonah Rockoff, “School Segregation, Educational Attainment, and Crime: Evidence from the End of Busing in Charlotte-Mecklenburg,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 129 (1) (2014): 435–476.

66. Billings, Deming, and Rockoff, “School Segregation, Educational Attainment, and Crime: Evidence from the End of Busing in Charlotte-Mecklenburg.”

67. Johnson, Children of the Dream: Why School Integration Works.

68. Billings, Deming, and Rockoff, “School Segregation, Educational Attainment, and Crime: Evidence from the End of Busing in Charlotte-Mecklenburg”; Kate Choi and others, “Class Composition: Socioeconomic Characteristics of Coursemates and College Enrollment,” Social Science Quarterly 89 (4) (2008): 846–866.

69. Johnson, “Long-Run Impacts of School Desegregation and School Quality on Adult Attainments”; Ulrich Boser and Perpetual Baffour, “Isolated and Segregated: A New Look at the Income Divide in Our Nation’s Schooling System” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2017).

70. Billings, Deming, and Rockoff, “School Segregation, Educational Attainment, and Crime: Evidence from the End of Busing in Charlotte-Mecklenburg”; Johnson, “Long-Run Impacts of School Desegregation and School Quality on Adult Attainments”; David J. Deming, “Better Schools, Less Crime?” Quarterly Journal of Economics 126 (4) (2011): 2063–2115.

71. Chase M. Billingham and Matthew O. Hunt, “School Racial Composition and Parental Choice: New Evidence on the Preferences of White Parents in the United States,” Sociology of Education 89 (2) (2016); Noah Berlatsky, “White parents are enabling school segregation — if it doesn’t hurt their own kids,” NBC News Thing blog, March 11, 2019; Maria Krysan and Kyle Crowder, Cycle of Segregation: Social Processes and Residential Stratification (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2017); Owens, “Inequality in children’s contexts: The economic segregation of households with and without children.”

72. Johnson, “Long-Run Impacts of School Desegregation and School Quality on Adult Attainments”; Gautam Rao, “Familiarity Does Not Breed Contempt: Generosity, Discrimination, and Diversity in Delhi Schools,” American Economic Review 109 (3) (2019): 774–809.

73. Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren, “The Impacts of Neighborhoods on Intergenerational Mobility I: Childhood Exposure Effects,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 133 (3) (2018): 1107–1162; Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren, “The Impacts of Neighborhoods on Intergenerational Mobility II: County-Level Estimates,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 133 (3) (2018) 1163–1228.

74. Rodney Andrews and others, “Location Matters: Historical Racial Segregation and Intergenerational Mobility,” Economics Letters 158 (2017): 67–72.

75. Rucker C. Johnson, “Can Schools Level the Intergenerational Playing Field? Lessons from Equal Educational Opportunity Policies.” In Economic Mobility: Research & Ideas on Strengthening Families, Communities & the Economy (St. Louis: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and Federal Reserve Board, 2016); Barbara Biasi, “School Finance Equalization Increases Intergenerational Mobility: Evidence from a Simulated-Instruments Approach.” Working Paper No. 25600 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2019).

76. Anthony Carnevale and others, “Born to Win, Schooled to Lose: Why Equally Talented Students Don’t Get Equal Chances to Be All They Can Be” (Washington: Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce, 2019).

77. N. Gregory Mankiw, David Romer, and David N. Weil, “A Contribution to the Economics of Economic Growth,” Quarterly Journal of Economics (1992): 407–437.

78. Claudia Goldin and Lawrence F. Katz, “Technology, Skill, and the Wage Structure: Insights from the Past,” American Economic Review 86 (2) (1996): 252–257; Claudia Goldin and Lawrence F. Katz, “The Legacy of U.S. Educational Leadership: Notes on Distribution and Economic Growth in the 20th Century,” American Economic Review 91 (2) (2001): 18–23.

79. Lisa D. Cook and Chaleampong Kongcharoen, “The Idea Gap in Pink and Black.” Working Paper (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2010); Lisa Cook and Jan Gerson, “The implications of U.S. gender and racial disparities in income and wealth inequality at each stage of the innovation process” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2019).

80. Will McGrew, “How workplace segregation fosters wage discrimination for African American women” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2018).

81. Chang-Tai Hsieh and others, “The Allocation of Talent and U.S. Economic Growth.” Working Paper (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2019).