Introduction

A fundamental challenge confronting the United States is how to generate faster and more widely shared economic growth, or equitable growth, now and well into the future. A large body of research across a variety of academic disciplines demonstrates that investments in the education of future workers can improve educational achievement and narrow socioeconomic-based achievement gaps, both of which can accelerate economic growth and promote more equal opportunity over time. Previous research shows that educational achievement and attainment are key determinants of both overall economic growth and individual earnings. This body of research, however, does not always identify how we can raise academic achievement or calculate the costs and benefits of investments that do so.

Download FileEarly-Childhood-Education-Report

This study describes and analyzes the costs and benefits of one specific educational initiative: public investment in a voluntary, high-quality universal prekindergarten education program made available to all 3- and 4-year-old children across the United States. Such an investment would boost educational achievement, improve economic growth rates, and raise standards of living across the income spectrum. It also would strengthen the economy’s competitiveness long into the future while simultaneously easing a host of fiscal, social, and health problems.

New report: By 2050, universal pre-k would yield $8.90 in benefits for every $1 invested https://t.co/39RAiyHMdf pic.twitter.com/aFKZ28AA3h

— Equitable Growth (@equitablegrowth) December 2, 2015

Publicly investing in high-quality prekindergarten provides a wide array of significant benefits to children, families, and society as a whole. Empirical research shows children who participate in high-quality prekindergarten programs score higher on tests when they enter kindergarten than do children who have not attended a high-quality prekindergarten, regardless of whether they are from poor, middle-income, or upper-income families. Children from low- to moderate-income families who attend high-quality prekindergarten require less special education and are less likely to repeat a grade or be victims of child abuse and neglect, thereby reducing the need for child welfare services. When these children become juveniles and adults, they are less likely to engage in criminal activity, reducing criminality overall. They graduate from high school and attend college at higher rates. Once these children enter the labor force, their incomes are higher, and so are the taxes they will pay back to society. As adults, they are likely to be in better health, with lower incidences of depression and reduced consumption of tobacco. In addition, research shows that quality matters: Higher-quality prekindergarten programs provide greater benefits than lower-quality programs.

High-quality prekindergarten also benefits government budgets by saving government spending on kindergarten through 12th-grade education, child welfare, the criminal justice system, and public health care. Higher tax revenues also flow into government coffers because of increasing taxes paid by participating children and their parents. Thus, investment in high-quality prekindergarten has significant implications for future government budgets, both at the national and the state and local levels, for the economy as a whole, for education, for crime, and for health.

This study breaks down these benefits at the national and state levels. The governmental costs and benefits of a publicly funded prekindergarten program—measured as year-by-year expenditures, budget savings, and revenue impacts—are estimated from program implementation in 2016 through 2050. In addition to the long-term budgetary consequences to governments, the earnings, health, and crime implications for individuals and society are calculated for these same years.

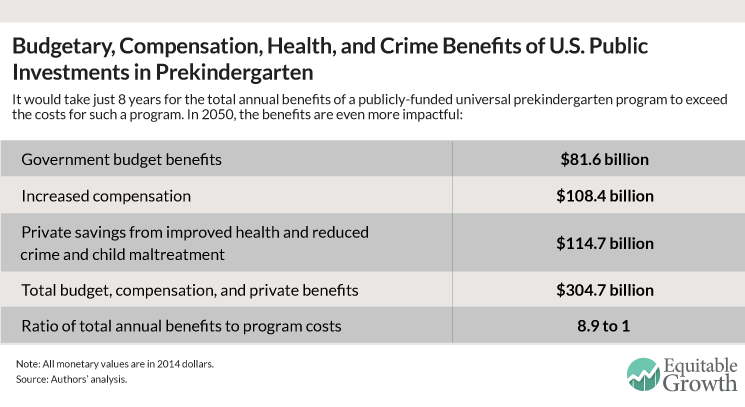

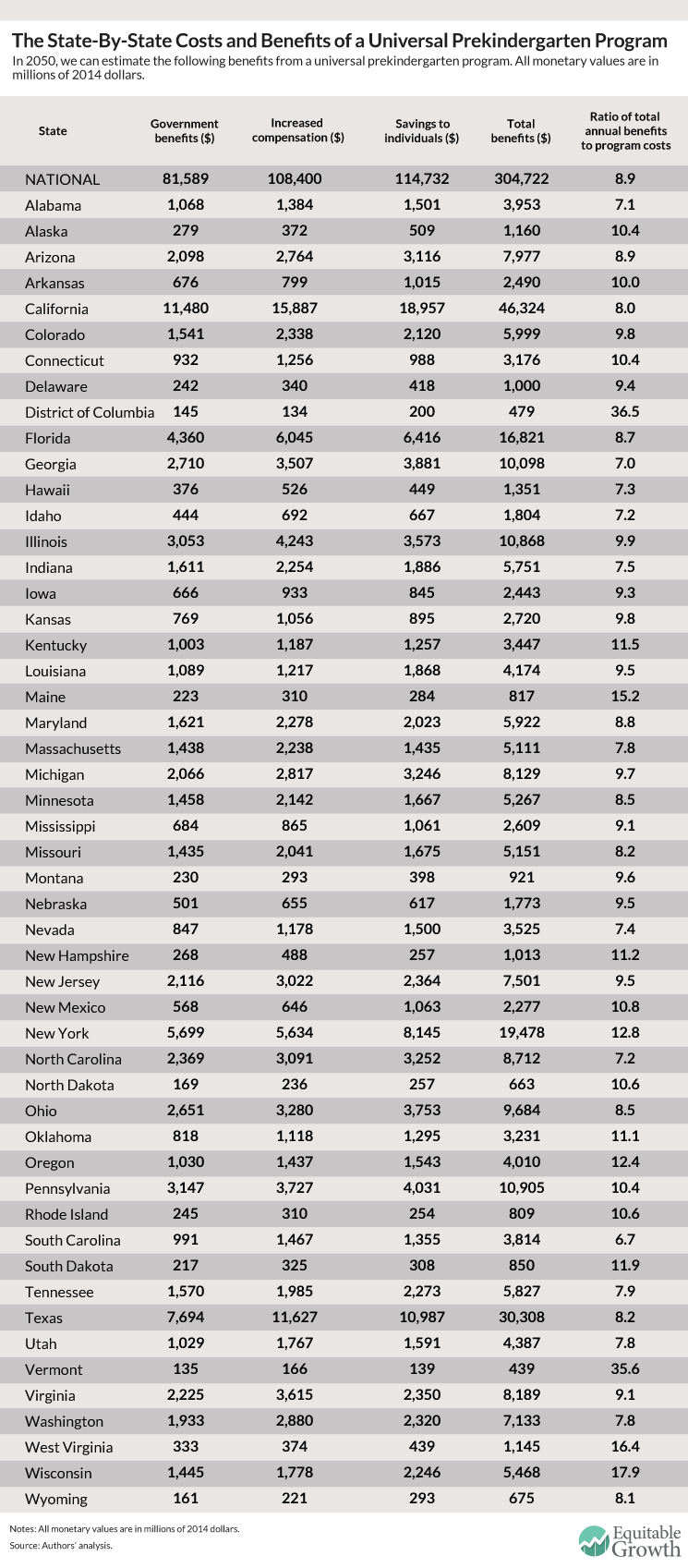

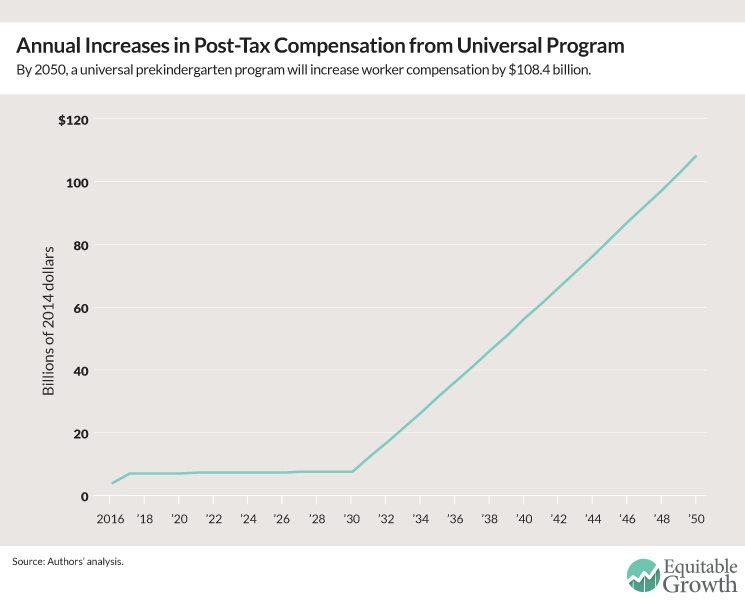

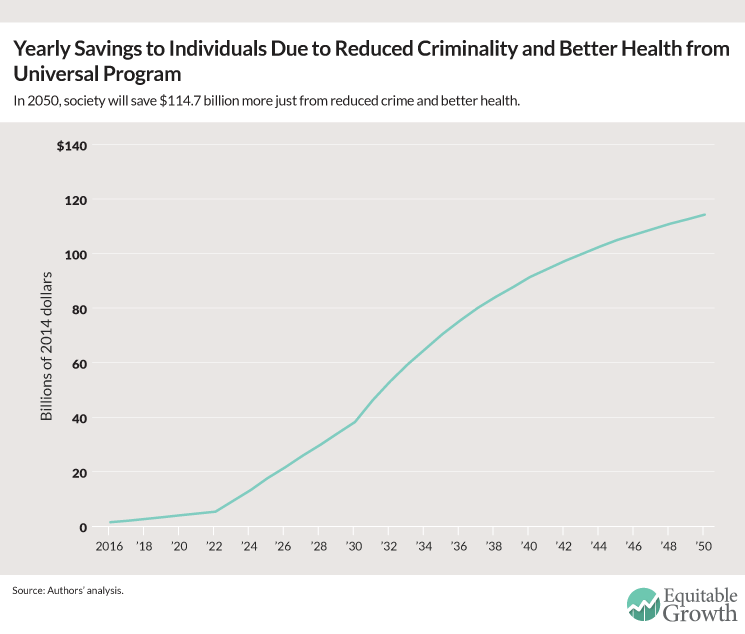

A voluntary, high-quality, publicly funded universal prekindergarten education program serving all 3- and 4-year-old children would generate annual benefits that would surpass the annual costs of the program within eight years. In the year 2050, the annual budgetary, earnings, health, and crime benefits would total $304.7 billion: $81.6 billion in government budget benefits, $108.4 billion in increased compensation of workers, and $114.7 billion in reduced costs to individuals from better health and less crime and child abuse. These annual benefits would exceed the costs of the program in 2050 by a ratio of 8.9 to 1. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

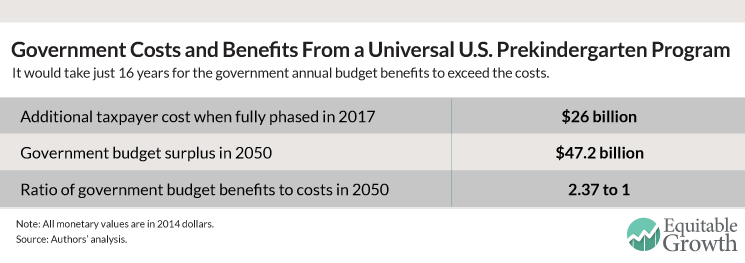

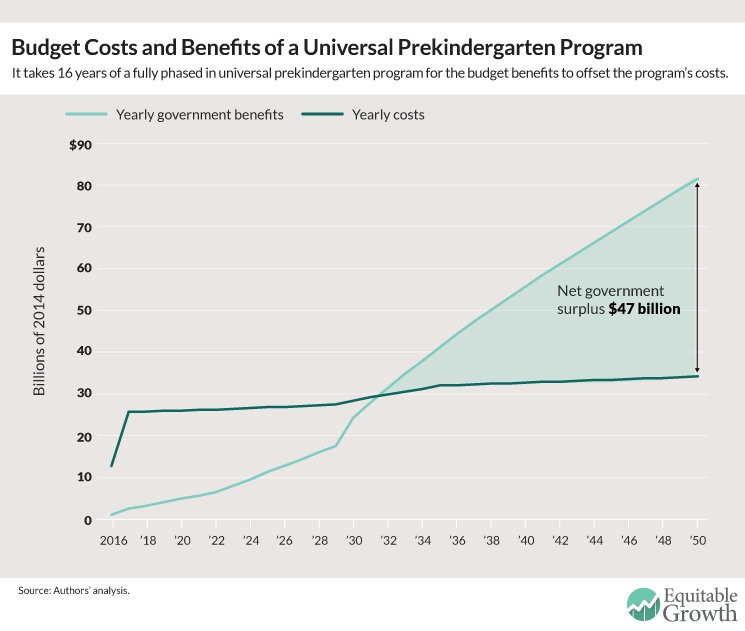

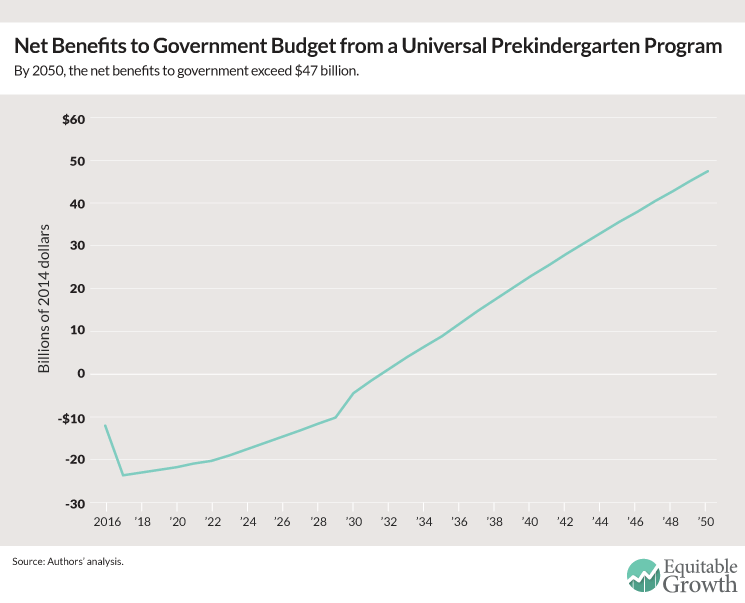

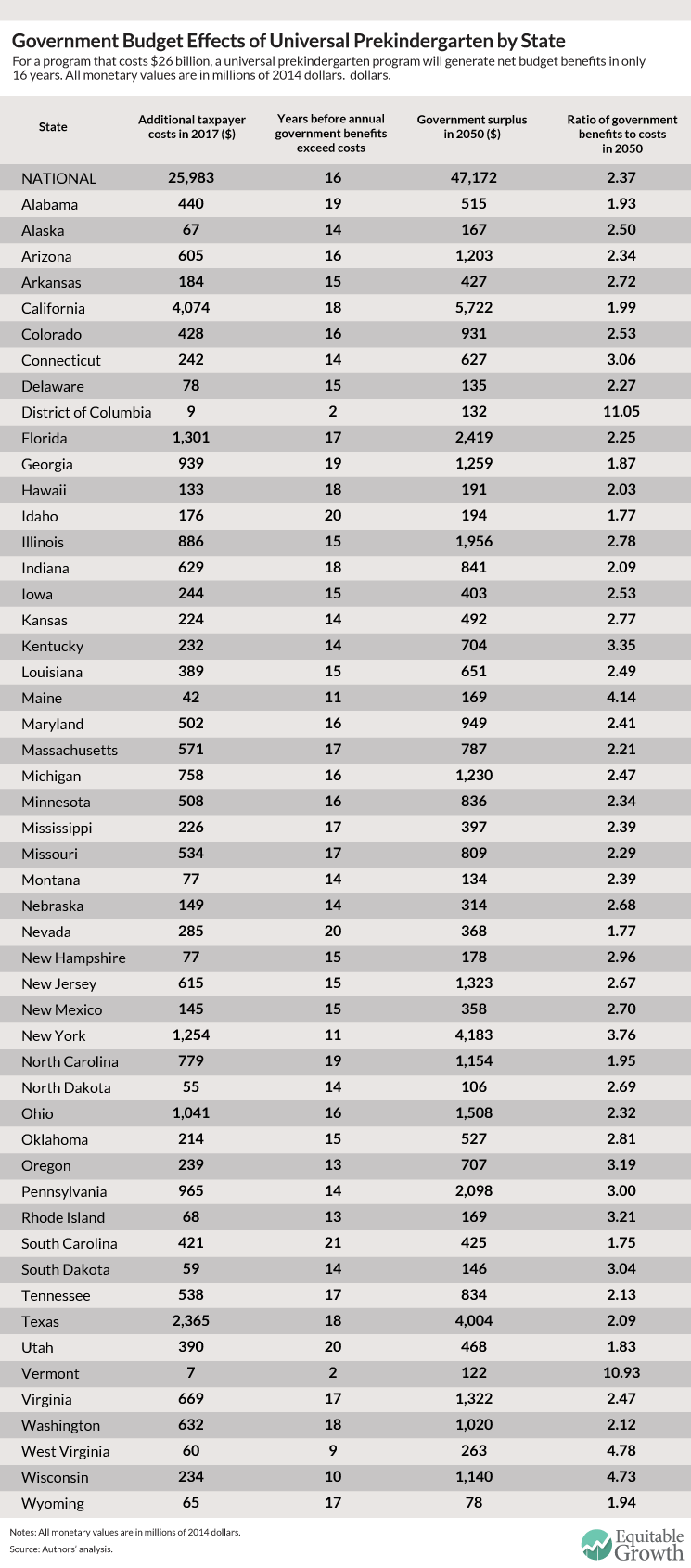

A high-quality prekindergarten program would cost $5,832 per participant and could be expected to enroll just under 7 million children when it is fully phased in in 2017. The program would initially cost taxpayers about $40.6 billion a year, but with offsets for current commitments to prekindergarten, this amounts to an additional $26 billion per year once it is fully phased in. Within 16 years, the net annual effect on government budgets alone would turn positive (for all levels of government combined). That is, starting in the 16th year and every year thereafter, annual government budget benefits due to the program would outweigh annual government costs of the program. Within 35 years, the offsetting budget benefits alone would total $81.6 billion, more than double the costs of the program. This means that by 2050, every tax dollar spent on the program would be offset by $2.37 in budget savings and governments collectively would be experiencing $47.2 billion in surpluses due to the prekindergarten investment. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

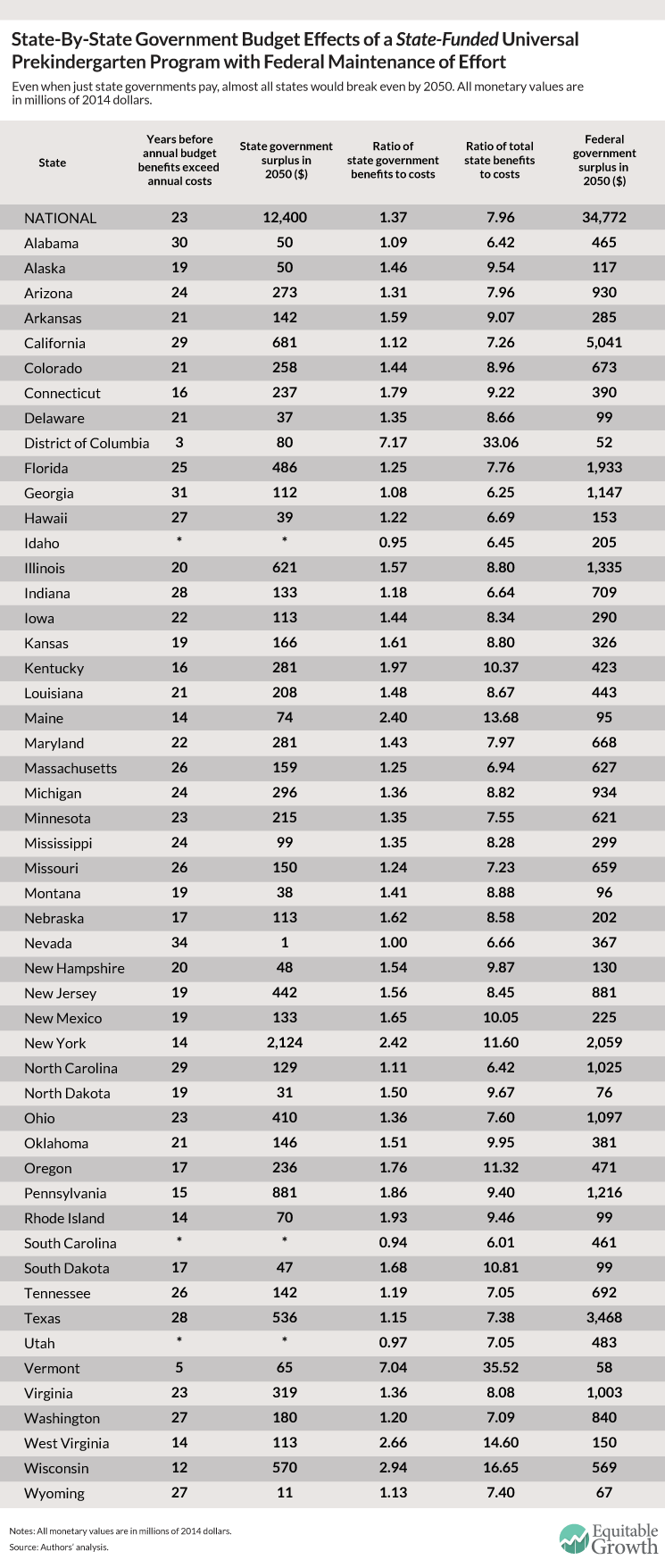

Even if states paid almost all the costs of the universal program, with the federal government simply maintaining its current commitments to prekindergarten education (holding states harmless from losses of federal funds and distributing prekindergarten commitments equitably among states), the program would be a boon to state budgets, generating budget surpluses in 47 states and the District of Columbia by 2050. When states pay the full cost of the universal program, only Idaho, South Carolina, and Utah do not generate budget surpluses by 2050 because their current commitments to early education are minimal. If we extend the analysis by four years to 2054, however, even these three states break even. Collectively, states would experience net budget savings within 23 years, and by 2050, every dollar spent on the program would be offset by $1.37 in budgetary savings for state governments.

The returns per state tax dollar spent on universal prekindergarten in 2050 would vary by state, from a low of 94 cents in South Carolina to a high of more than $7.00 in Vermont and the District of Columbia. And by 2050 the federal government would register a prekindergarten investment-related budget surplus of $34.8 billion.

Regardless of whether the program is state or federally funded, by the year 2050, a voluntary, high-quality universal prekindergarten education program is estimated to increase the compensation of workers by $108.4 billion and reduce the costs to individuals from crime, child abuse, depression, and tobacco consumption by $114.7 billion. Thus, even if states paid almost all the costs, the total state benefits of the program would outstrip the state program costs in every state in 2050 assuming the federal government maintains its current commitments to prekindergarten education. The benefits vary from a minimum of 6.7 to 1 in South Carolina to as much as 36.5 to 1 in the District of Columbia. In other words, when evaluated from the perspective of total costs and benefits, and not just government budget costs and benefits, the program pays for itself in every state several times over.

The increase in worker compensation of $108.4 billion by the year 2050 is estimated to accrue disproportionately to lower- and middle-income individuals because research shows that these workers of tomorrow benefit the most from higher-quality prekindergarten programs. In addition, a high-quality universal prekindergarten program increases the gross national product of the United States—the total value of all goods and services produced in our economy—by $234 billion in 2050, or approximately 0.6 percent. Both of these factors indicate that public investment in high-quality prekindergarten will generate faster and more widely shared economic growth.

A nationwide commitment to high-quality early childhood education would cost a significant amount of money upfront—an estimated $26 billion per year when it is fully phased in. But over time, strikingly, governmental budget benefits alone would outweigh the costs of high-quality prekindergarten education investment.

In short, high-quality prekindergarten pays for itself, and it benefits public balance sheets, children, their families, taxpayers, and society as a whole. Accordingly, policymakers should consider a universal prekindergarten initiative as a sound public investment with long-term returns.

The potential of prekindergarten

The ultimate aim of public policy is to promote the well-being of the nation, including its individuals, families, and communities. When determining whether a particular policy is worth pursuing, it is often useful to weigh the benefits of the policy against its costs. Yet it is not always possible to measure or quantify in dollar terms all the benefits or costs of a particular policy.

The benefits of public investment in early childhood education are difficult to comprehensively and precisely quantify. Research tells us that public investment in effective early childhood education improves educational outcomes, enhances the quality of life of the recipients, and creates a range of external benefits to society over and above those to individual students. But it is not easy to translate all of these improvements into dollar terms. Likewise, while education may be associated with greater levels of life and job satisfaction, it is no simple task to quantify the monetary value of increases in the quality of life. Many of the external benefits to society from early childhood education, such as the future greater productivity of more educated workers, are similarly challenging to quantify.

Still, many (though not all) of the benefits to individuals and society from early childhood education investment can be calculated. The costs of public investment in early childhood education are relatively easier to capture fully and accurately. Hence, we can compare the quantifiable benefits and costs—and even when the benefits are not fully accounted for, such a comparison can inform the public debate on the merits of public investment in early childhood education.

This study analyzes the costs and many, but not all, of the benefits of public investment in the education of children during the early childhood years. Specifically, this study looks at the costs and the fiscal, earnings, crime, and health benefits of public investment in a voluntary universal prekindergarten education program made available to all 3- and 4-year-olds. The analysis demonstrates that investment in early childhood education, even when its benefits are not fully accounted for, may be an effective public policy strategy for generating growth, raising standards of living, and achieving a multitude of social and economic development objectives.

No single policy can bring about the rapid and simultaneous achievement of all of our economic and social goals, but just as clearly, policies do matter. And at a time of sharp disagreement over solutions to the many social and economic problems we confront, we should take particular notice when a consensus emerges across the political spectrum on an effective policy strategy such as a universal prekindergarten program. There is general agreement that high-quality prekindergarten education in particular has the ability to powerfully impact many of our socioeconomic development goals and positively influence the pace of economic progress.

The consequence of relatively poor educational performance on future economic growth

But first, it is important to provide some context. It may be contentious to state that many American children, whether they come from poor, middle-income, or wealthy families, do not have adequate access to high-quality educational opportunities and, as a result, fall short of achieving their academic potential while in school. But what is not debatable is that American children’s academic achievement is poor in comparison to children living in other wealthy countries. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, comprised of 34 developed or rapidly developing nations, provides data on comparative student achievement across the member nations through its Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, ranking countries by the reading, science, and math skills of their 15-year-olds. Several other studies, such as the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study and the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study, also provide insight into the academic achievement of American children compared to children in other nations. In all of these studies, American children tend to rank at the middle or bottom of the pack. The situation is more dismal when we consider that several of the countries ranked lower than the United States are not direct economic peers; in fact, they are much poorer nations such as Chile, Mexico, and Turkey.

These relatively poor academic achievement rankings have consequences. In a recent study, we calculated the consequences for economic growth, lifetime earnings, and tax revenue of improving educational outcomes and narrowing educational achievement gaps in the United States.1 Among other results, we found that if the United States were able to raise the math and science PISA test scores of the bottom three quarters of U.S. students so that they matched the test scores of the top quarter of U.S. kids (and thereby raised the overall U.S. academic ranking to third best among the OECD countries), U.S. GDP would be 10 percent larger in 35 years. Simply matching the OECD average math and science PISA scores by narrowing educational achievement gaps between socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged American children would raise U.S. GDP by 1.7 percent over 35 years.

Within the discipline of economics, there has long been near-universal agreement that educational achievement and attainment are fundamental elements of success in the labor market. Education provides skills, or human capital, that raise an individual’s productivity and future earnings.2 Children above and below the poverty line who fail to reach their full academic potential are more likely to enter adulthood without the skills necessary to be highly productive members of society able to compete effectively in a global labor market. Less skilled, less productive, and earning less, these children will be less able to contribute to the growth and development of our economy when they become adults.

Closing Education Gap Will Lift Economy, Study Finds http://t.co/7kAwW9JVHO

— The New York Times (@nytimes) February 3, 2015

But there is hope. Research demonstrates that investment in early childhood education is one of the best ways to improve child well-being and increase the educational achievement and productivity of children and adults. Such investment is also one of the best ways to help us attain numerous other socioeconomic goals. It is interesting to note that economists’ conclusions about the effectiveness of investment in early childhood education are buttressed and strongly supported by the findings of scholars in a variety of other fields of inquiry, including medicine, neurobiology, and developmental psychology.

Consider the following from Stanford University neurobiologist Eric Knudsen; Nobel Prize-winning economist James Heckman from the University of Chicago; University of Pittsburgh Professor of Psychiatry, Neuroscience, Obstetrics-Gynecology Reproductive Sciences, and Clinical and Translational Science Judy Cameron; and Harvard University Professor of Child Health and Development Jack Shonkoff:

A cross-disciplinary examination of research in economics, developmental psychology, and neurobiology reveals a striking convergence on a set of common principles that account for the potent effects of early environment on the capacity for human skill development. Central to these principles are the findings that early experiences have a uniquely powerful influence on the development of cognitive and social skills, as well as on brain architecture and neurochemistry; that both skill development and brain maturation are hierarchical processes in which higher level functions depend on, and build on, lower level functions; and that the capacity for change in the foundations of human skill development and neural circuitry is highest earlier in life and decreases over time. These findings lead to the conclusion that the most efficient strategy for strengthening the future workforce, both economically and neurobiologically, and for improving its quality of life is to invest in the environments of disadvantaged children during the early childhood years.3

Findings from economics and other disciplines are increasingly indicating that “prevention is more effective and less costly than remediation, and earlier is far better than later.”4 Appropriately, there is growing consensus that investment in the education of young children, especially disadvantaged children, is one of the most effective strategies to develop the workforce of the future, ameliorate the quality of life, and enhance the well-being of individuals, families, communities, societies, and nations.

Overview of the benefits of early childhood development programs

A strong consensus has developed among experts who have studied high-quality early childhood development programs that these programs have substantial and enduring payoffs. Long-term studies of early childhood development participants, especially prekindergarten participants, consistently find that investing in children has a large number of lasting, important benefits for the participants, their families, and society at large (including taxpayers). These benefits include:

• Higher levels of verbal, mathematical, and general intellectual achievement

• Greater success at school, including less grade retention, less need for special education, and higher graduation rates

• Less welfare dependency

• Better health outcomes

• Higher employment and earnings

• Greater government revenues and lower government expenditures

• Lower crime rates

More specifically, assessments of well-designed and well-executed programs in early childhood development have established that participating children are more successful in school and in life after school than children who are not enrolled in high-quality programs. In particular, children who participate in high-quality early childhood development programs tend to have higher scores on math and reading achievement tests and greater language abilities. They are better prepared to enter elementary school, experience less grade retention, and have less need for special education and other remedial coursework. They have lower dropout rates, higher high school graduation rates, and higher levels of schooling attainment. They also experience less child abuse and neglect and are less likely to be teenage parents. Additionally, they have better nutrition, improved access to health care services, higher rates of immunization and better health.

As adults, high-quality prekindergarten recipients have higher employment rates, higher earnings, greater self-sufficiency and lower welfare dependency. They exhibit lower rates of drug use and less frequent and less severe delinquent behavior, engaging in fewer criminal acts both as juveniles and as adults and having fewer interactions with the criminal justice system, and lower incarceration rates. They also have better health outcomes such as fewer episodes of depression and less tobacco use. The benefits of early childhood development programs to participating children enable them to enter school “ready to learn,” helping them achieve better outcomes in school and throughout their lives.

Parents and families of children who participate in early childhood development programs also benefit. They benefit both directly from the services they receive in high-quality programs and indirectly from the subsidized child care provided by publicly funded early childhood development programs. In general, parents take advantage of the child care these programs provide by investing in their own health and education and by increasing their employment and earnings. Mothers have fewer additional births, have better nutrition and smoke less during pregnancy, and are less likely to abuse or neglect their children. Parents complete more years of schooling, have higher high school graduation rates, are more likely to be employed, have higher earnings, engage in fewer criminal acts, have lower rates of drug and alcohol abuse, and are less likely to use welfare.

Investments in early childhood development programs pay for themselves over time by generating high rates of return for participants, the non-participating public, and government. Good programs produce $3 or more in present value benefits for every dollar of investment. Present value estimates are the value in today’s dollars of future revenues discounted at a specified of rate of interest. While participants and their families get part of the total benefits, the benefits to the rest of the public and government can be larger and, on their own, tend to far outweigh the costs of these programs. Thus, it is advantageous even for non-participating taxpayers to help pay for these programs.

Kids need high quality #ece early in life: https://t.co/SVb3vLuUxO

— Prof. James Heckman (@heckmanequation) October 28, 2015

Several prominent economists and business leaders have recently issued well-documented reviews of the literature that find very high economic payoffs from early childhood development programs. Nobel Laureate James Heckman concludes that:

Recent studies of early childhood investments have shown remarkable success and indicate that the early years are important for early learning and can be enriched through external channels. Early childhood investments of high quality have lasting effects […] In the long run, significant improvements in the skill levels of American workers, especially workers not attending college, are unlikely without substantial improvements in the arrangements that foster early learning. We cannot afford to postpone investing in children until they become adults, nor can we wait until they reach school age – a time when it may be too late to intervene. Learning is a dynamic process and is most effective when it begins at a young age and continues through adulthood. The role of the family is crucial to the formation of learning skills, and government interventions at an early age that mend the harm done by dysfunctional families have proven to be highly effective. 5

The former director of research and an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Arthur Rolnick and Rob Grunewald, come to similar conclusions:

[Recent] studies suggest that one critical form of education, early childhood development, or ECD, is grossly under-funded. However, if properly funded and managed, investment in ECD yields an extraordinary return, far exceeding the return on most investments, private or public. […] In the future any proposed economic development list should have early childhood development at the top. 6

Likewise, after reviewing the evidence, the Committee for Economic Development, a nonpartisan research and policy organization of business leaders and educators, finds that:

Society pays in many ways for failing to take full advantage of the learning potential of all of its children, from lost economic productivity and tax revenues to higher crime rates to diminished participation in the civic and cultural life of the nation. […] Over a decade ago, CED urged the nation to view education as an investment, not an expense, and to develop a comprehensive and coordinated strategy of human investment. Such a strategy should redefine education as a process that begins at birth and encompasses all aspects of children’s early development, including their physical, social emotional, and cognitive growth. In the intervening years the evidence has grown even stronger that investments in early education can have long-term benefits for both children and society. 7

In a follow-up review of the evidence, the Committee for Economic Development further concludes that:

[It] has become generally accepted that preschool programs play an important role in preparing children – both advantaged and disadvantaged – to enter kindergarten. There is also a consensus that children from disadvantaged backgrounds in particular should have access to publicly supported preschool programs that provide an opportunity for an “even start.” 8

The social equity arguments for preschool programs have recently been reinforced by compelling economic evidence that suggests that society at large benefits from investing in these programs. Broadening access to preschool programs for all children is a cost-effective investment that pays dividends for years to come and will help ensure our states’ and our nation’s future economic productivity.

Estimates of the benefits and costs of prekindergarten investment

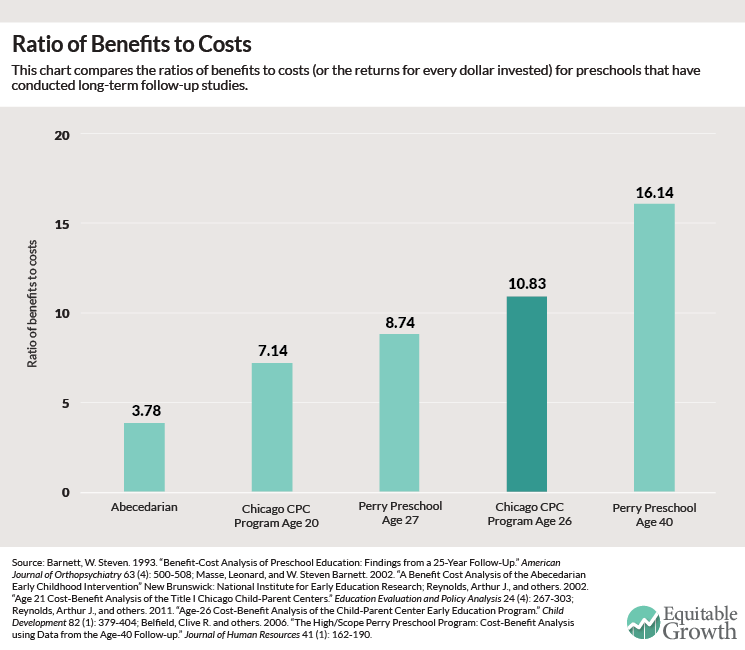

Three prekindergarten programs have been the subject of carefully controlled studies of their benefits and costs with long-term follow-up of participants and a control group of non-participants: the Perry Preschool Project, the Abecedarian Early Childhood Intervention, and the Chicago Child-Parent Center Program.9 All of these studies have found that enormous payoffs result from investments in early childhood development. Specifically, analyses of the three programs for disadvantaged children have found benefit-cost ratios that varied from a minimum of 3.78 to 1 to a high of 16.14 to 1, expressed in net present value. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

It should be noted that investment in a project is justified if its benefits are greater than its costs or if its benefit-cost ratio exceeds 1 to 1.10 Moreover, in the benefit-cost analyses of all three of these programs, the costs may have been fully described but the benefits were certainly understated.11 Thus, the benefits of these prekindergarten programs probably exceed the costs by margins greater than those indicated in Figure 3.

It is interesting to note that the benefit-cost ratios do not fade as the children age and researchers are able to analyze additional data. Compare, for instance, the Chicago results at age 20 (7.14 to 1) with those at age 26 (10.83 to 1) and the Perry results at age 27 (8.74 to 1) with those at age 40 (16.14 to 1) in Figure 3. This suggests that the benefits of prekindergarten are not ephemeral. On the contrary, as noted by others, they are sustained and may grow larger over time.12

From the perspective of public policy, investments in prekindergarten programs pay for themselves by generating very high rates of return for participants, the non-participating public, and government (in the form of either reduced public service costs or higher tax payments by participants and their families). While participants and their families get part of the total benefits, it is noteworthy that the benefits to the non-participating public and government are larger and, in and of themselves, tend to outweigh the costs of these programs.

Consider, for example, the benefit-cost analysis of the Chicago Child-Parent Center program when the participants were at age 26. The study found that of the total return of $10.83 per dollar invested, $7.20 went to people other than the program participants and their families.13 Likewise, a Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis study determined that annual real rates of return (after adjusting for inflation) on public investments in the Perry Preschool prekindergarten program were 12 percent for the non-participating public and government, and 4 percent for participants, so that total returns exceeded 16 percent.14 These analyses suggest that it is advantageous even for non-participating taxpayers to pay for these programs. To comprehend how high these rates of return on prekindergarten investments are, consider that the highly touted real rate of return on the stock market that prevailed between 1801 and 2006 was 6.8 percent.15

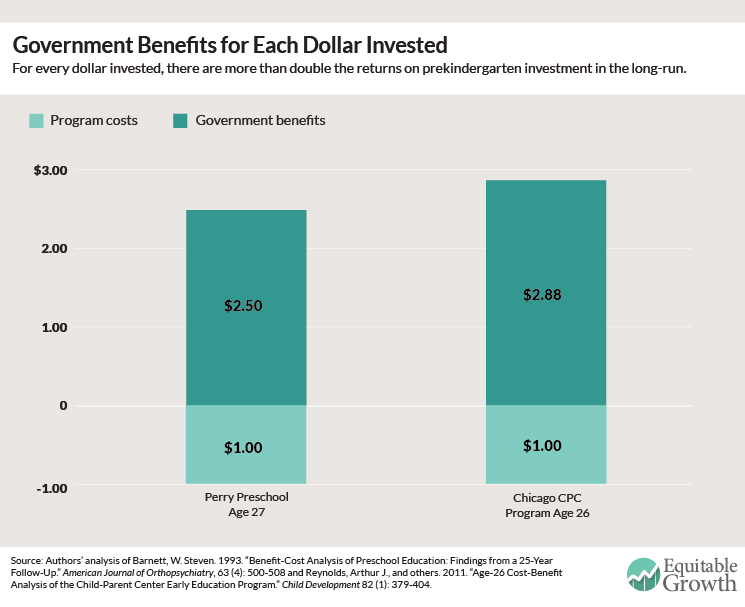

Even from the narrow perspective of budgetary policy, investments in prekindergarten programs pay for themselves because the costs to government are outweighed by the positive budget impacts that the investments eventually produce. Take, for instance, the benefit-cost ratio for two of the three prekindergarten programs described in Figure 1, assuming that all the costs are borne by government and taking into account only the benefits that generate budget gains for government.16 These ratios vary from 2.5 to 1 for the Perry Preschool program to 2.88 for the Chicago Child-Parent Center program by age 26. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

Earlier research has not usually translated these calculations of benefits and costs into estimates of how investments in prekindergarten programs affect future government finances, the economy, health, and crime. This study presents such an analysis based in large part on the outcomes of the Chicago Child-Parent Center Program.17 Since the outcomes of this program are used as the basis for the analysis carried out in the third section of this report, in the next section we describe in detail the long-run effects of this high-quality prekindergarten program. The third section describes the budgetary, economic, health, and crime effects of a voluntary, universal, high-quality, publicly financed prekindergarten education program for all 3- and 4-year-old children. Both the national and state-level effects of prekindergarten are discussed. The calculations used to carry out the extrapolations in the third section are explained in the methodology section.

High-quality pre-k and the Chicago Child-Parent Center program

This section begins with a brief description of the general characteristics of high-quality prekindergarten programs. Then, the Chicago Child-Parent Center program is described in particular detail, as it is the basis of the benefit-cost estimates described in the following section. In particular, the outcomes, and the pedagogy and other factors that account for the success of the Chicago Child-Parent Center program will be described.

What makes a prekindergarten program high-quality?

The quality of preschool education is typically measured by two standards: structure and process. Structure is categorized as the tangible characteristics of preschool education programs such as child-to-teacher ratios, teacher pay, teacher qualifications, and class size, while process refers to the social experiences in the classroom such as the nature of teacher-child interactions, the relationships with parents, the diversity and quality of activities and instructional materials, and the health and safety procedures.

A high-quality prekindergarten program boasts low child-to-teacher ratios (10 to 1, or better), small class sizes (20, or less), and highly paid, well-qualified teachers and staff. Teachers are typically required to have at least a bachelor’s degree with a specialization in early childhood education, and classroom assistants usually have at least a child development associate’s degree or equivalent. In high-quality preschools, both teachers and assistants are encouraged and given opportunities to continue their professional development, and parental involvement in the education process is cultivated. The nature of teacher-child interactions tends to be warm, positive, supportive, and stimulating.

The activities in the classroom and the instructional materials vary with emphasis placed on quality instruction in a wide range of subjects, among them art, music, science, math, problem-solving, language development, and reasoning. From a programmatic side, high-quality preschools provide meals and offer health services (such as hearing, vision, and psychological health screenings) for their students. All of these aspects of high-quality programs are upheld and improved through rigorous monitoring to ensure that quality standards are being met or exceeded.

High-quality, publicly funded universal preschools in the United States

There are few examples across the country of high-quality and publicly funded universal programs. Generally, the existing publicly funded, large-scale programs vary in quality and audience. Head Start is by far the most well-known and largest early childhood intervention program in the United States. Though Head Start offers early education, development, health, and nutrition services, it is largely targeted at low-income preschool students, and there is substantial variation in how the programs are administered locally, though they must comply with federal standards and quality guidelines. Currently, only five states (Florida, Georgia, Oklahoma, Vermont, and West Virginia) have a publicly funded, universal voluntary prekindergarten program that offers services to all 4-year-olds. The District of Columbia also has a universal prekindergarten program, but unlike the five state programs, it is open to 3-year-olds as well as 4-year-olds.

Perhaps the best example of a high-quality publicly funded prekindergarten program with long-term outcome follow-up studies is Chicago’s Child-Parent Centers.

Chicago Child-Parent Centers

Established in 1967, the Child-Parent Center program, or CPC, provides center-based, comprehensive educational and family-support services to economically disadvantaged preschoolers (children ages 3 and 4) and early elementary students from several of Chicago’s poorest neighborhoods. The program was initiated with federal funding from Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, and its prekindergarten and kindergarten components are still supported by those federal allocations. After Head Start, CPC is the oldest federally funded prekindergarten program in the nation.

Early childhood education is one of the best investments we can make! https://t.co/f4P4k0SiXI

— Chicago Longitudinal (@CLS_ChiSurvey) October 26, 2015

The CPC programs are administered by the Chicago Public School system. To be eligible for enrollment in the CPC, children must live in neighborhoods that receive Title I funding for schools. Eligible children must not be enrolled in another preschool program, and their parents must agree to participate in their child’s classroom at least one half-day per week. In practice, however, parent participation tends to be lower.

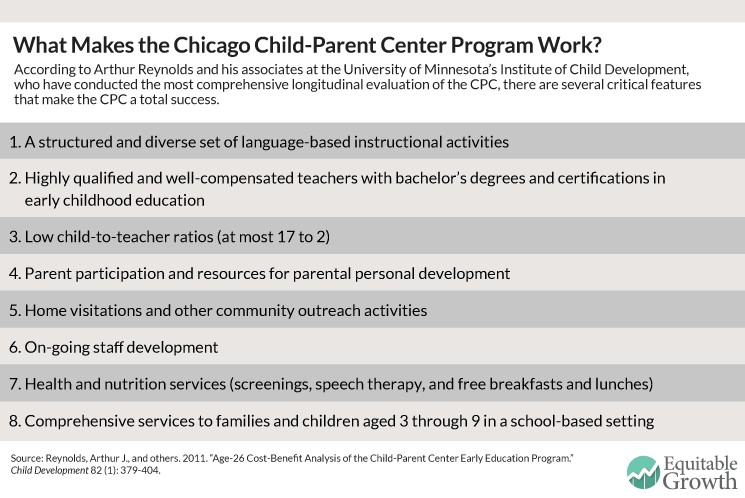

Children typically enter the program at age 3 for a half-day of prekindergarten (either a morning or afternoon session of three hours) and attend the program for the regular nine-month school year for a total of 540 hours. Generally, the preschoolers are exposed to small peer groups, with classrooms including at most 17 students and at least two staff members. These small classrooms foster an effective learning environment, as children learn basic language, reading, and math skills. Teachers also place importance on the students’ social, psychological, and physical development.

Teachers in the CPC program have at least a bachelor’s degree along with a certification in early childhood education.18 Staff compensation is relatively high compared to most preschool staff, mirroring the salary schedule of the Chicago Public School system, which reduces teacher turnover.19 In addition to teachers and classroom aides, students also are monitored by parent volunteers, home visit representatives, clerks, nurses, speech therapists, and other administrative staff who are associated with the public school program. Similar to other high-quality programs, the Chicago CPC program also provides funds and time for ongoing professional development for teachers, classroom aides, and community representatives alike. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

The Chicago Longitudinal Study

The Chicago Longitudinal Study began in 1999 and has been following a cohort of 1,539 low-income students who were born in 1980. The 989 children who completed the Chicago CPC prekindergarten program were compared to a control group of 550 children who did not attend the preschool program but had participated in full-day kindergarten. Of the 550 children in the control group, 161 attended a CPC kindergarten program even though they had not attended the CPC preschool program. Data on both the intervention and control groups are collected periodically by Arthur Reynolds and his colleagues at the University of Minnesota’s Institute of Child Development, with the most recent published results for the group by age 26.20

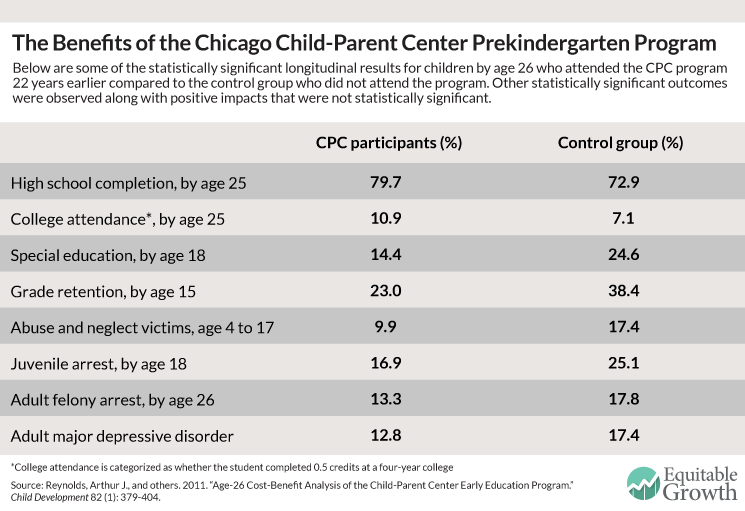

Figure 6 summarizes some of the statistically significant outcomes of the CPC preschool program as reported by Reynolds and colleagues.21 The results shown here are only for 3- and 4-year-olds in the prekindergarten program.

Figure 6

The Chicago Longitudinal Study demonstrates that there are significant benefits from attending the CPC program. The study finds that the children who attended the program had significantly higher test scores at ages 5, 6, 9, and 14 than non-center students. CPC participants also spent less time in special education and had lower grade retention rates. Between the ages of 4 and 17, 10 percent of the students experienced child maltreatment in the form of abuse and neglect, while more than 17 percent of non-CPC participants were victims.

Juvenile and adult crime rates were also significantly lower for CPC students. By age 18, roughly 17 percent of participants had been arrested—a stark contrast to a juvenile delinquency rate of 25 percent in non-participants. Similarly, adult crime by age 26 was 13 percent for participants and close to 18 percent for non-participants. Reynolds and his colleagues also observe the long-term health benefits from attending a high-quality prekindergarten program. The prevalence of adult major depressive disorder in participants is lower (13 percent) than it is for non-participants (17 percent). Adult smoking rates also diminish for participants versus non-participants (18 percent versus 22 percent), although the declines were not statistically significant.

Reynolds and his colleagues carry out a benefit-cost analysis of the Chicago Child-Parent Center program. For the prekindergarten program alone, they identified $92,220 in present value benefits and $8,512 in present value costs in 2007 dollars—a benefit-cost ratio of 10.83 to 1.22 The benefits derived mainly from reduced public education expenditures due to lower grade retention and use of special education, reduced costs to the criminal justice system and victims of crime due to lower crime rates, reduced expenditures on child welfare due to less child abuse and neglect, higher projected earnings of center participants, and increased income tax revenue due to projected higher lifetime earnings of center participants.

http://t.co/iF3skAptgL

PreK is a great investment! CLS results suggest that for every $1 invested, society saves an average of $7 long-term— Chicago Longitudinal (@CLS_ChiSurvey) June 8, 2015

The benefits of the program, however, underestimate the savings from reduced adult welfare, as welfare usage on the part of center participants was not calculated. In addition, neither the likely benefits to the center participants’ offspring nor the value of the likely increase in parental earnings, due to the child care provided by the preschool, were included in the calculations.

In 2012, the CPC prekindergarten program was expanded to four school districts in Illinois and Minnesota. The scaled-up model, known as the Midwest Expansion of the Child-Parent Center Education Program (Midwest CPC), includes a fortified curriculum and a more economically and racially diverse cohort of preschoolers. Early results from these new sites reveal very similar results to the Chicago Longitudinal Study: Participants had higher mean scores for literacy, language, math, cognitive development, socio-emotional development, and physical health compared to non-participants, suggesting that the program has promising benefits for children today.23 These positive results were consistent across socioeconomic and racial groups, further reinforcing the CPC model’s effectiveness in cultivating school readiness skills and potentially other long-term benefits for all children.

We will use the findings detailed in Figure 6 and other results from this latest study as the baseline for treatment effects in our methodology.24 In the next section, we will describe the characteristics of our proposed high-quality universal prekindergarten, explain two of the key assumptions underlying our methodology, and discuss the fiscal, economic, earnings, health, and crime effects of the prekindergarten program.

The effects of universal pre-k on finances, crime, and health

The research literature reviewed earlier in our report establishes that high-quality prekindergarten education programs can generate significant long-run benefits for program participants, their families, and other non-participants. In this section, we translate the measured consequences of the Chicago CPC program into estimates of how public investment in a universal, high-quality prekindergarten program would affect future government finances, the economy, crime, and health. The methodology used to arrive at the estimates presented below is explained in detail in the appendix.

In the following subsections, we first describe the characteristics of the proposed high-quality universal prekindergarten program. Next, we discuss two determinations we made about the effects of high-quality prekindergarten on non-low-income children and on children who would, in its absence, attend some other form of preschool. Then, we describe the costs and benefits of the proposed prekindergarten program over the next 35 years through 2050. These include its effects on the economy, government budgets, private savings from reduced crime and better health, and the compensation of workers.

(In the next section of the report, we discuss the costs and benefits that have been omitted in our analysis; as explained there, the benefits that we were not able to quantify in dollar terms are likely to be much greater than the omitted costs. As a result, the overall benefits and the benefit-cost ratio of a universal pre-K education program are likely to be higher than those we have presented in this paper.)

Characteristics of the proposed high-quality universal prekindergarten program

To estimate the long-run costs and benefits of a universal preschool education program, we must make assumptions about the characteristics of the program. Our study assumes that a prospective universal preschool would take the form of a voluntary, high-quality, publicly funded prekindergarten program that is modeled on the Chicago Child-Parent Center program, described in detail earlier in our report. The proposed program would operate 3 hours per day, 5 days a week, for 36 weeks a year (the traditional school year) or a total of 540 hours.25 The program would be available to all 3- and 4-year-old children regardless of family income.26

Classrooms in this prospective program would be small: Each classroom would contain a maximum of 17 children. Additionally, each classroom would have at least two overseeing staff members, a lead teacher and a teaching assistant, which would permit a low student-to-teacher ratio of 17 to 2. The lead teachers in a classroom would all have bachelor’s degrees (or higher) with certification in early childhood education. They would also be encouraged to pursue professional development opportunities. The teaching assistant in each class would have at least an associate’s degree. As a further incentive for quality, teacher and staff pay would be high relative to most existing preschool programs. Their compensation would follow the salary schedules of the public schools.

Each classroom’s curriculum would have a strong focus on language and pre-reading skills, mathematics such as counting and number recognition, science, social studies, health and physical development, and social and emotional development. The prekindergarten program would also provide several auxiliary services such as health screenings, speech therapy services, and home visitations, allowing for comprehensive monitoring of a child’s educational, physical, mental, and social development.

Further, parental involvement in the form of volunteering or classroom engagement would be encouraged. We assume that the prekindergarten education program would be housed in public schools, community centers, or private child care centers that meet quality standards. All costs of the prekindergarten program would be paid for with public funds.

The effects of high-quality prekindergarten on non-low-income children and children who would, in its absence, attend some other form of preschool

Numerous studies have examined the long-term effects of prekindergarten programs on the outcomes of participating children. Yet most of these studies have focused on low-income children and children at high risk for educational failure. Prekindergarten programs that have served children from middle- and upper-income families have generally not been subject to carefully controlled studies with long-term follow-up of participants and a control group of non-participants. Thus, the effects of prekindergarten programs on middle- and upper-income children are not as well understood.

Still, there are good reasons to expect that a universal program would generate significant benefits but not generate the same magnitude of benefits per participant or the same high rate of return as a program targeted to relatively disadvantaged children. There are also reasons to believe that the benefits of a high-quality prekindergarten program like the Chicago Child-Parent Centers, which served high-risk children from low-income families, will not apply fully to medium-risk children (from middle-income families) and low-risk children (from high-income families) who would otherwise attend no prekindergarten.

Finally, there are reasons to believe that the benefits of a high-quality prekindergarten program like the Chicago CPC program—one that compared outcomes for children who attended a high-quality prekindergarten program to outcomes for children who (for the most part) attended no prekindergarten—will not apply fully to children who would otherwise attend some form of preschool education program. Children who are likely to enroll in a public universal program may be somewhat more likely to otherwise attend some form of preschool education in comparison to children who attend targeted programs. This means that the benefits per participant and the overall benefit-to-cost ratio of a universal prekindergarten program are likely to be smaller than those of a more targeted prekindergarten program.

At the same time, the total benefits of a universal program will be larger than those of a targeted program to the extent that benefits of prekindergarten for middle- and upper-income children exist. The ratio of benefits to costs of a universal program, while smaller than that for a targeted program, may still be large enough to justify public investment in a universal program. But to estimate the costs and benefits of a universal prekindergarten program, we have to address the caveats described above. Specifically, we have to make two key determinations:

• To what extent will the benefits of a high-quality, prekindergarten program like the Chicago CPC program, which served high-risk children (from low-income families), apply to medium-risk children from middle-income families and low-risk children from high-income families who would otherwise attend no prekindergarten?

• To what extent will the benefits of a high-quality prekindergarten program, like the Chicago CPC program that compared outcomes for children who attended a high-quality prekindergarten program to outcomes for children who (for the most part) attended no prekindergarten, apply to children who would otherwise attend some form of prekindergarten?

In answer to the first question, as detailed in the appendix, the empirical research shows that all children, regardless of whether they are from poor, middle-income or upper-income families, benefit from high-quality prekindergarten. But studies differ on the degree of impact that prekindergarten has on children from different economic backgrounds. Some studies find that the positive effects of prekindergarten on children from more- and less-advantaged backgrounds are nearly identical. Other studies suggest that children from low-income families gain more from prekindergarten than do children from middle- and high-income families. Finally, some studies suggest that for some skills, lower-middle-income children gain more than poorer or wealthier children.

Differential benefits for children from different socioeconomic backgrounds manifest themselves in at least two ways. First, there is a baseline effect: Different socioeconomic groups have different rates of everything from special education to child abuse to criminal behavior to smoking. These different baselines can be thought of as “room-for-improvement” effects. Second, there may be a differential treatment effect: For reasons not captured fully by the baseline differences, different children may see greater or lesser treatment effects from prekindergarten. Our estimating procedure takes into account both of these factors, using a variable-specific estimate for the first factor based on data for the diverse levels of social and academic problems experienced by children from different family incomes. For the second factor, we use an average estimate of the relative impact of prekindergarten on children from different family incomes.

For the second factor, we also use the available empirical data to calculate a likely range of these possible effects: high (100 percent), low (40 percent), and intermediate or most likely (79 percent) estimates. In the discussion below describing the estimated costs and benefits of the program, we use the intermediate range estimate. But a sensitivity analysis is performed (described later on) to demonstrate what effect different estimates have on the final results. Taking into account both factors—baseline adjustments and treatment effect attenuations—our intermediate estimate assumes that middle- and upper-income children receive on average only 56 percent of the reduction in the need for special education, 28 percent of the decline in grade retention, 16 percent of the reduction in child maltreatment, 55 percent of the drop in juvenile and adult crime, 49 percent of the decrease in smoking, and 34 percent of the lessening of depression experienced by relatively disadvantaged children.

In answer to the second question, again discussed in much greater detail in the appendix, the literature shows that there is evidence that existing prekindergarten programs (private and public) provide important benefits to participants compared to children who attend no prekindergarten. In addition, higher-quality prekindergarten programs provide greater benefits than lower-quality programs. Hence, children moving from low- or medium-quality prekindergarten to high-quality prekindergarten should not gain as much as children moving from no pre-K to high-quality pre-K. We use empirical data to provide a range of estimates: high (100 percent), low (30 percent), and intermediate or most likely (76 percent).27 In our estimates below of the costs and benefits of a voluntary, high-quality universal prekindergarten program, we use the intermediate estimate but our sensitivity analysis includes the results from the full range of estimates.

Combining baseline adjustments, treatment attenuation effects, and prior preschool attendance attenuation effects, we assume that non-low-income children experience 42 percent of the reduction in the need for special education, 21 percent of the decline in grade retention, 12 percent of the reduction in child maltreatment, 42 percent of the drop in juvenile and adult crime, 26 percent of the lessening of depression, and 37 percent of the decrease in smoking experienced by low-income children.28

Enrollment in universal prekindergarten

Given that the prospective universal prekindergarten program would be both voluntary and available to all 3- and 4-year-olds, we had to estimate its prospective enrollment. As explained in detail in the methodology appendix, based on the enrollment rates for the five states and the District of Columbia that have publicly funded universal pre-K programs, we assume that the enrollment rate would be approximately 86 percent. Below, we translate the measured impacts of the Chicago CPC program into estimates of how public investment in a universal, high-quality, prekindergarten program would affect future government finances, the economy, earnings, and crime and health, using the attenuations described above for children from middle- and upper-income families, and for children who in its absence would have attended some other preschool.

Total benefits of investment in a universal prekindergarten program

The annual budgetary, earnings, health, and crime benefits of a voluntary, high-quality, publicly funded, universal prekindergarten program would begin to outstrip the annual costs of the program within eight years after full phase-in and would do so by a growing margin every year thereafter. By the year 2050, the annual benefits would total $304.7 billion: $81.6 billion in government budget benefits, $108.4 billion in increased compensation of workers, and $114.7 billion in reduced costs to individuals from less crime and child maltreatment and better health. These annual benefits in 2050 would exceed the costs of the program in that year by a ratio of 8.9 to 1. Broken down by state, in 2050 the total annual benefits would outstrip the annual costs of the program by a minimum of 6.7 to 1 for residents of South Carolina and by as much as 36.5 to 1 for the residents of the District of Columbia. (See Figure 7.)

The District of Columbia and Vermont stand out with particularly high ratios of total annual benefits to program costs. This can be attributed to the fact that they both already have high levels of prekindergarten enrollment in state-sponsored programs and are investing heavily in them. It would take relatively little investment beyond what is already being provided to support a universal prekindergarten program in either of these places, and both areas would experience significant budgetary benefits from the cost-sharing with the federal government that is proposed in this study. Although neither area would experience significantly greater benefits from universal prekindergarten than would other states, the additional costs of providing universal prekindergarten in the District of Columbia and Vermont would be relatively low, and the ratio of benefits to costs would thus be high. (The annual costs and budgetary, earnings, crime, and health benefits are further detailed below.)

Figure 7

Budget effects of investments in a universal prekindergarten program

We examine the budget effects through the year 2050 of launching a voluntary, high-quality universal prekindergarten program in 2016 for all 3- and 4-year-old children in America. For illustration purposes, we assume that the program would be fully phased in by 2017. We consider budget effects on the federal government and the combination of state and local governments. We also examine the budget effects on a state-by-state basis. Although responsibilities have shifted in the past and will continue to do so in the future over the 35-year timeframe used in this study, we assume that all levels of government will share in the costs of education, child welfare, criminal justice, and health care in the future in the same proportions as they do today. Likewise, we assume that federal, state, and local tax rates will remain constant over the time period analyzed in this study. All the costs and benefits are expressed in real (inflation-adjusted) 2014 dollars.

We initially assume that the costs of the prekindergarten program will be evenly split between the federal and state governments. We will then examine the scenario where state governments pick up the full cost of the prekindergarten program.

A high-quality universal pre-K program would cost a little over $5,800 per participant and could be expected to enroll nearly 7 million children in 2017 when it is fully phased in. As a result, the program would cost taxpayers about $40.6 billion in 2017. Some of this money, however, is already being spent on related programs. Case in point: Forty states and the District of Columbia have publicly financed prekindergarten programs for children, some of whom would be enrolled in our proposed program. Similarly, states and the federal government pay for special education and Head Start services for young children, some of whom would attend our proposed program instead.

Hence, some of the current expenditures on state prekindergarten programs and some of the current expenditures on special education and Head Start services are for children who will be attending the proposed universal prekindergarten program. We assume that these expenditures would be used to pay for part of the proposed program. The bottom line is that our proposed high-quality universal prekindergarten program would require approximately $26 billion in additional government outlays in 2017, once it is fully phased in.

Government costs initially reflect only the actual expenditures on the prekindergarten program. Eventually there will be some additional government expenditures due to the increased educational attainment of the preschool participants: Prekindergarten participants spend more time in high school and college because they are less likely to drop out of high school and more likely to go on college. Increased public costs at the high school level appear when the first cohort of participants turns 17, and increased higher education costs appear when the first cohort turns 18.

The offsetting budget savings begin small but grow rapidly over time, eventually outstripping the costs. Budget savings in the first year of the program will manifest themselves as reductions in child welfare expenditures as fewer children will be the victims of child abuse and neglect. In addition, some parents will take advantage of the universal prekindergarten program for some of their child care needs, allowing them to work more and, thus, pay more in taxes. When the prekindergarten participants enter the K-12 public school system, additional budget savings will begin to appear, as these children will be less likely to repeat a grade or need expensive special education services. When the first cohort of children turns 10, further budget savings will begin to be realized as lower juvenile crime rates will require less expenditure on the juvenile justice system. As adults, the prekindergarten participants will be less engaged in crime and working and earning more. Thus, there will eventually be savings to the adult criminal justice system and increased tax revenue derived from the labor of prekindergarten participants. In addition, as adults, the pre-K participants will experience fewer episodes of depression and reduced rates of smoking, which will reduce public health care system expenditures.

For the first 15 years of a fully phased-in national universal prekindergarten program, costs exceed offsetting budget benefits, but by a declining margin. Starting in 2032, offsetting budget benefits exceed costs by a growing margin each year. Annual revenue impacts and costs are portrayed in real terms in Figure 8. Figure 9 shows the annual net budget impact in real terms.

Figure 8

In the second year of the program, 2017, when the program is fully phased in, government outlays exceed offsetting budget benefits by $23 billion. The universal pre-K program-related deficit shrinks for the next 14 years. By the 16th year of the program, in 2032, the deficit turns into a surplus that grows every year thereafter culminating in a net budgetary surplus of some $47.2 billion in 2050, the last year estimated, as illustrated in Figure 9. Thus, by 2050, every dollar spent on the program by taxpayers is offset by $2.37 in budget savings in that year.

Figure 9

The reason for the fiscal pattern seen in Figure 9 is because the costs of the program grow fairly slowly for the first decade and a half, in tandem with inflation and modest growth in the population of 3- and 4-year-old participants. But as the first and subsequent cohorts of participant children begin to use more high school and public higher education services, the costs grow at a somewhat faster pace for a few years. Budget benefits during the first two years result from reductions in child welfare spending due to lower rates of child maltreatment and from increased taxes on the earnings of parents due to subsidized child care. After the first two years, when the first cohort of children starts entering the public school system, public education expenditures begin to diminish due to less grade retention and need for special education. After a decade and a half, the first cohort of children begins entering the workforce, resulting in increased earnings and thus higher tax revenues.

In addition, governments eventually experience lower judicial system costs due to less juvenile and, later, adult crime, starting when the first cohort of prekindergarten participants reaches age 10. Governments also experience lower public health care costs starting when the first cohort reaches age 18 as they have fewer episodes of depression and lower tobacco usage.

If the federal government did not share in the costs of the universal preschool program, the program would still be a worthwhile investment from the narrow perspective of state budgetary savings for most states.29 States as a whole would experience net government budget savings within 23 years (2039), and by 2050, every tax dollar spent on the program would be offset by $1.37 in budgetary savings for state governments. And in this scenario the federal government would be enjoying $34.8 billion in surpluses in 2050.

State-by-state budget effects of a universal prekindergarten program

Our state-by-state estimates capture variation in costs and benefits due to factors such as population, income distribution, teacher salaries, crime rates, health care costs, tax burdens, and current expenditures on all levels of education, child welfare, criminal justice, and health care. If the cost of the universal prekindergarten program is shared evenly by the federal and state governments, then all states eventually realize budget benefits from a universal prekindergarten investment, but the timing and size of the benefits varies.

In 2017, a high-quality universal prekindergarten program enrolling nearly 7 million children nationwide would enroll as few as 11,800 children in the small state of Vermont and more than 891,000 children in the large state of California when it is fully phased in. Given offsets for expenditures on Head Start, special education, and existing state prekindergarten, the program (which would cost $26 billion nationwide) would cost from as little as an additional $6.7 million in Vermont to as much as an additional $4.1 billion in California in 2017. (See Figure 10.)

Figure 10

Offsetting budget benefits (federal and state combined) outstrip costs nationwide within 16 years, but at the state level timing varies substantially. The total (federal and state) offsetting budget benefits exceed costs by state in as little as two years (2018) in the District of Columbia and Vermont and in as many as 21 years (2037) in South Carolina.

These differences in state budget benefits are driven by a multitude of factors. In general, states with greater current relative commitments to prekindergarten and other education programs, child welfare programs, criminal justice programs, and health care and those with higher tax burdens experience greater offsetting budget benefits than do other states. States with greater current commitments to state prekindergarten programs need less additional public expenditure to finance the proposed high-quality prekindergarten program than do states with smaller current commitments to state pre-K programs. Since the proposed prekindergarten program generates budget savings in special education, K-12 education, child welfare, juvenile and adult criminal justice, and health care, states who are making larger financial commitments in these areas save more money than states who are making smaller financial commitments in these areas. Likewise, since the prospective prekindergarten program increases the future earnings of participants and their guardians, states with higher average pay and higher tax burdens will experience greater revenue increases than will states with lower average pay and lower tax burdens.

As noted above, by 2050, the last year estimated, the net nationwide budgetary surplus (federal and state combined) totals $47.2 billion. The corresponding state-level surpluses due to the program vary from $78 million in Wyoming to $5.7 billion in California. Also previously noted, this yields a return to taxpayers averaging $2.37 in offsetting budget benefits for every dollar spent on the program nationwide in 2050. The total return to state-level implementation is also favorable for every state. By 2050, for example, for every dollar being spent on the program in that year, a program in South Carolina will create $1.75 in budget savings, and every dollar invested in the program in Vermont, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia would return to taxpayers more than $10 in budget savings.

If the federal government does not share in the costs of the prekindergarten program and only maintains its current investments, the program generates budget surpluses in 47 states and the District of Columbia by 2050.30 The three outlier states—Idaho, South Carolina, and Utah—also would generate budget surpluses but not until three or four years after 2050. Collectively, states experience net budget savings in 23 years (2039) with an average return per state tax dollar expended on the program of $1.37 in 2050, but the returns per state tax dollar vary from a low of $0.94 in South Carolina to a high of more than $7 in Vermont and the District of Columbia in 2050. And in 2050, the federal government would be enjoying $34.8 billion in budget surplus due to the prekindergarten investment made largely by states. (See Figure 11.)

Figure 11

It is important to understand that the ratio of government budget benefits to program costs in 2050 is a cash analysis that compares the impact on net government expenditures from the program to the additional taxpayer costs engendered by the program in 2050. Thus, for a publicly financed prekindergarten program, the government budget-to-cost ratio considers all the additional costs due to the program—but only the additional government budgetary benefits of the program—thereby ignoring the compensation, crime, and other benefits. Hence, the individual state government budget-to-cost ratios in Figure 11 indicate that from the taxpayers’ perspective alone, the program fully pays for itself in 2050 in 47 states. This is an extraordinary finding as it may be rare to find government expenditures on a program creating offsetting budget savings such that the public program pays for itself at the budgetary level. And looking just three or four years further out, the three states where the budget benefits alone do not cover the costs of the program in 2050 would do so if we extended the window of analysis.

Of course, once we add in the other benefits of the program, the universal prekindergarten program more than pays for itself in all 50 states. Indeed, the ratio of total state benefits to state program costs in 2050, when states pay for the universal program and the federal government simply maintains its current efforts in prekindergarten, varies from a minimum ratio of 6.01 to 1 in South Carolina to 35.53 to 1 in Vermont. In fact, the non-budgetary benefits of the prekindergarten program are by themselves much greater than the costs of the program in all 50 states. Consequently, the budget benefits, even those in the few states where the budget benefits do not exceed the additional costs of the program in 2050 when states pay for most of the program, should be seen as bonuses that are in addition to the other non-budgetary benefits.

Economic effects of investment in a universal prekindergarten program

It would be unwise to judge the merits of investments in prekindergarten solely in terms of its budgetary effects. Government investments can affect the quality of life of citizens, justifying their expense even if their net costs are very large. Our national defense program, for example, generates hundreds of billions of dollars annually in budget deficits that may be justified by the collective national security those fiscal outlays provide.

The benefits of prekindergarten include the health and well-being of citizens, the earnings of workers, crime rates, global competitiveness, and numerous other factors. Many of these other benefits may not be easily defined or measured in financial terms, just as the value of collective national security may be difficult to monetize. But these other benefits still exist. Some of the non-budgetary benefits of prekindergarten, however, are measurable in dollar terms. Indeed, benefits that did not accrue to government finances but were measurable represented a sizeable portion of the total benefits found in studies of high-quality prekindergarten programs. In fact, 73 percent of the estimated total benefits found for the Chicago Child-Parent Centers program and 81.4 percent of the total benefits of the Perry Preschool program went to groups aside from government.31

Among the other quantifiable benefits of prekindergarten investment are its impact on the future economy and the earnings of participants and the guardians of participants. Our research shows that the impact of a universal pre-K program on the economy increases the compensation (wages plus fringe benefits) of participants who attend prekindergarten and their parents. The initial increase in earnings and compensation occurs in 2016 when some of the guardians of prekindergarten participants take advantage of the subsidized child care provided by the pre-K program and enter the labor force or increase the hours they work. Later, in 2031, when the first cohort of participating children turns 18 and enters the labor market, there is a sharp increase in earnings and compensation. By 2050, the increase in post-tax compensation due to prekindergarten investment amounts to $108.4 billion and results in an economy that is $234 billion or 0.6 percent larger in 2050 than it otherwise would have been. This averages to an increase in compensation of $1,832 (in 2014 dollars) for each pre-K participant plus an increase in average compensation of $1,202 (in 2014 dollars) for the guardians of each prekindergarten participant prior to taxes. (See Figure 12.)

Figure 12

The increased compensation for guardians estimated here is likely to be conservative, as we assume that guardians gain only during the two years in which their child is enrolled. In reality, two additional years of labor force participation early in a career are likely to generate beneficial earnings effects for the rest of a worker’s life. These increased earnings are not captured in the above estimates.

In addition, and more importantly, our estimated increase in earnings and GDP growth is likely to be understated because we assume no feedback effects on the economy from the increased earnings. In other words, we do not take into account the fact that prekindergarten participants and their guardians are likely to spend a significant part of their increased earnings, thereby stimulating demand, business sales, production, job creation, and economic growth.

State-by-state compensation gains from universal prekindergarten investment

By 2050, the post-tax increase in compensation due to universal prekindergarten investment is estimated to vary from $134 million in the District of Columbia and $166 million in Vermont to more than $15.9 billion in California. (See Figure 7.) The average increase in pre-tax compensation per each pre-K participant varies from less than $1,500 (in 2014 dollars) in West Virginia, Oklahoma, Louisiana, and the District of Columbia to $2,462 in New Hampshire. The increase in the average compensation of the guardians of pre-K participants varies from less than $600 in the District of Columbia, Vermont, and West Virginia to more than $1,700 in Alaska (both expressed in 2014 dollars).

Total state-by-state differences in compensation gains are largely due to differences in population, with more-populated states experiencing greater total compensation gains than less-populated states. But state-by-state variations in compensation gains also are due in part to the fact that state-by-state earnings were adjusted to reflect average annual pay variation by state. As a result, states with relatively high average annual pay experience larger compensation gains per pre-K participant and their guardians than do states with relatively low average annual pay.

Crime and health effects of universal prekindergarten investment

Investments in a universal prekindergarten program would reduce crime rates and improve health outcomes, thereby reducing the extraordinary costs to society of criminality and health care. Some of these reduced costs are savings to government in the form of lower criminal justice system costs and public health care spending. These savings to government would total about $26.7 billion in 2050 and were included in our earlier discussion of the fiscal effects of universal pre-K investment.

But there are other savings to society from reduced crime and better health. These include the value of material losses and the pain and suffering that would otherwise be experienced by the victims of juvenile crime, adult crime, and child abuse and neglect as well as the reduced private medical expenses to individuals from less smoking and depression. By 2050, these savings to individuals from less crime and better health amount to $114.7 billion. Including the savings to government, the savings to society from reductions in criminality and better health due to investments in a universal pre-K program total $141.5 billion. Figure 13 illustrates the benefits to individuals from prekindergarten-induced improvements in health and reductions in crime.

Figure 13

State-by-state crime and health savings from universal prekindergarten

The public health care and criminal justice savings to state governments in 2050 were included in our earlier discussion of the fiscal effects of universal pre-K investment. But the private individual health care and crime savings, by state, were not. By 2050, the savings to individuals from less child abuse and crime and better health amount to $138.5 million in Vermont and to $19 billion in California. (See Figure 7.)

Total crime and health savings will tend to be larger in states with large populations than in ones with small populations, where there are fewer total crimes. But variations in state-by state crime and health savings are also due in part to variations in current state financial commitments to child welfare, criminal justice, and health care. States that are spending relatively more on their child welfare programs, criminal justice system, and health care infrastructure will save relatively more than states that make smaller relative commitments in these areas. Similarly, savings to individuals from less crime and child abuse will tend to be greater in states with relatively high crime and child abuse rates compared to states with relatively low crime and child abuse rates.

Aside from positive budget implications, earnings effects, and crime and health impacts, there are other benefits from a high-quality pre-K program that we have not evaluated. There may have been costs that we have omitted from our analysis as well. Many of these costs and benefits are difficult to measure or monetize. Some of these omitted costs and benefits are described in the next section.

Omitted costs and benefits of targeted and universal prekindergarten

The ultimate costs and benefits of a nationwide universal prekindergarten program enrolling nearly 7 million children per year could turn out to be higher or lower than what we have estimated. For illustration purposes, this analysis assumes the launch of a universal pre-K program on a national scale immediately in 2016, with full phase-in by 2017. But for practical purposes—such as the recruitment and training of teachers and staff, and the finding of appropriate locations—a large-scale pre-K program would have to be phased in over a longer period. There may be start-up costs associated with the scaling up of pre-K investment that have not been considered. Likewise, the quality of teachers and other staff may not be as good, or the teachers and staff may not be as highly motivated, as those in the Chicago CPC program, which would adversely affect the benefits of the program.