Introduction

Taxing capital is a key way to maintain and increase the progressivity in the U.S. tax system and raise the revenue needed to support government activities and investments that in turn will help ensure strong and sustainable economic growth. Why turn to capital as a source of government revenue? Taxing capital is a highly progressive form of taxation that research suggests does not seriously affect the rate of savings among high-income Americans—an important consideration in terms of encouraging future economic growth—and is a key part of optimal taxation in the United States. Yet the federal tax rate paid on capital income is, on average, relatively low, due to a combination of factors including low existing rates, special tax breaks, and the gaming of the system to avoid paying taxes on capital.

Download FileTaxing Capital Report

Effectively defending and expanding the taxation of capital will involve significant reform. Specifically, the United States currently taxes capital income using tools that are too easy to avoid. As a result, simply increasing tax rates, whether on capital gains, corporations, or on wealthy estates, will not be successful at generating much additional revenue or significantly improving the progressivity of the tax system. Instead, tax reform should focus on ways of making taxes harder to avoid by owners of capital and possibly by adding additional tax tools as ways of more effectively taxing capital. Absent reforms along these lines, it will be very difficult to expand or even maintain the current system for taxing capital in the United States.

This report specifically identifies three key areas where the taxation of capital in the United States deserves fundamental reforms and also lays out some intermediate steps that policymakers can take first. Specifically, these reforms would address:

- Taxes on gains on property that are too easy to reduce or avoid entirely

- The shifting of corporate profits and corporate residence to avoid taxes

- Wealth taxes that apply to only a sliver of the population and are too easily avoided

These three areas for the reform of capital taxation are not meant to be fully comprehensive but rather zero in on some of the main challenges in taxing capital and the policy instruments that should be deployed in response. Enacting these reforms would strengthen the progressivity of the U.S. tax code, help reduce income inequality, and enable the country to invest in future economic growth and stability.

What is capital and why tax it?

This report focuses on the major challenges that this country faces in trying to tax capital and how to address those challenges in order to encourage stronger and more equitable economic growth. But before reaching those questions, this section briefly reviews what capital is, why it should be taxed, and why multiple instruments for doing so are appropriate.

Defining capital

Thomas Piketty of the Paris School of Economics and the author of the bestseller, “Capital in the Twenty First Century” offers a compelling definition of capital in his now renowned volume on the subject. In his words, capital is the “total market value of everything owned by the residents and government of a given country at a given point in time, provided that it can be traded on some market.”1 To put this somewhat differently and in terms of an individual, someone’s capital is that person’s net worth or that person’s total amount of assets less liabilities.2 Each of these definitions—though framed somewhat differently—arrives at roughly the same place. In this report, the word “capital” is used interchangeably with the word “wealth.”

There are a few important characteristics of capital relevant to this report and to the question addressed in the next section of why we tax capital. One is that the ownership of capital and the income derived from capital is highly concentrated. A second is that it can be hard to distinguish between capital and the returns to capital, and accrued earnings from labor.

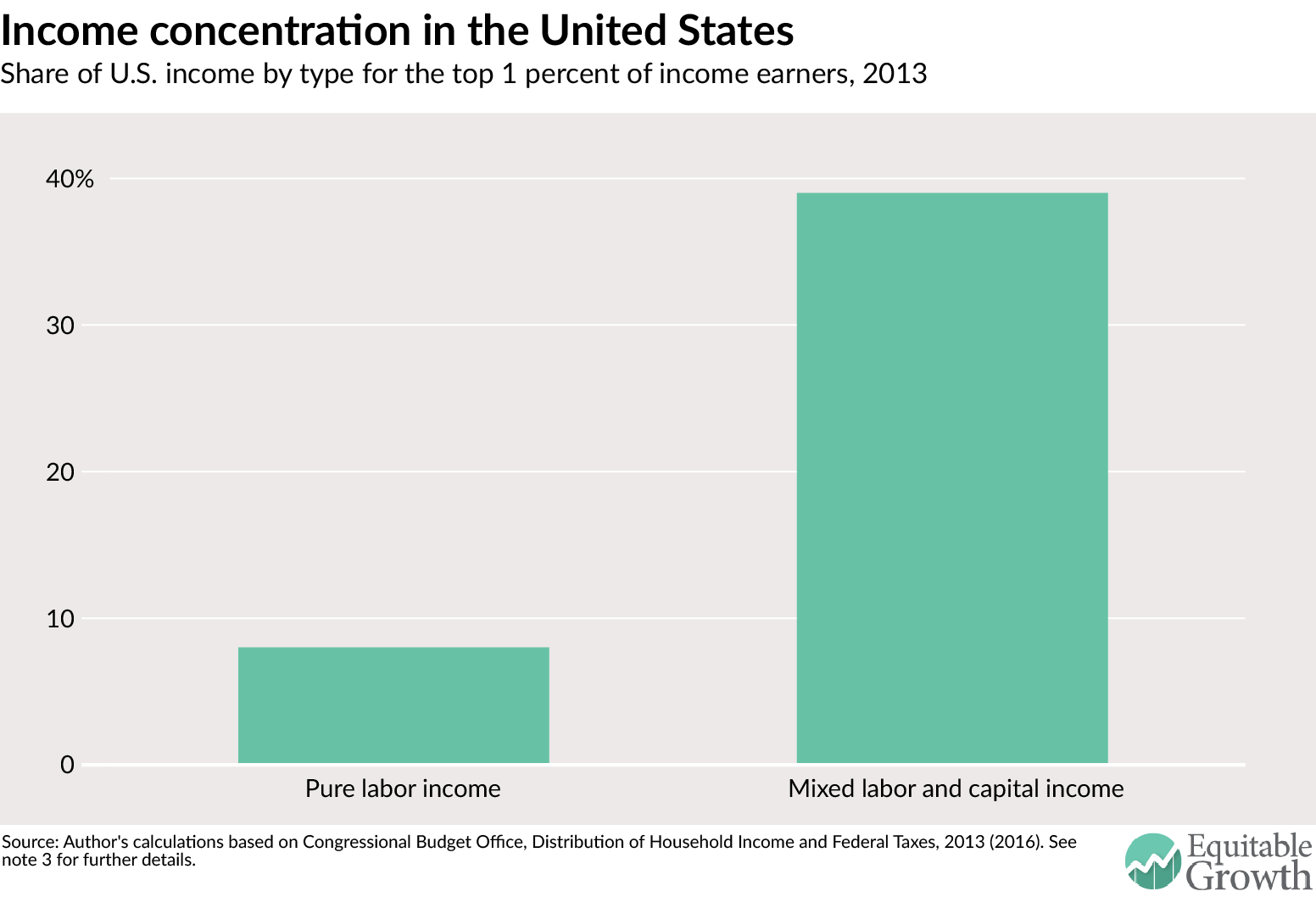

For instance, the top 1 percent of earners in the United States earned a little under 10 percent of total purely labor income in 2013, the last year for which complete data are available. In other words, just under one out of every ten dollars of purely labor income—mostly in the form of wages and employee benefits—went to the top 1 percent of income earners. But, in 2013, they earned around 40 percent of income that is some mixture of returns to capital and labor, such as interest income, capital gains, and business income.3 (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

This is consistent with estimates for the concentration in ownership of the capital itself—the capital producing these returns. One estimate of wealth concentration—based on the federal government’s Survey of Consumer Finance—finds that the top 1 percent owns 36 percent of net wealth as of 2013, taking into account financial assets, non-financial assets (but not human capital), and liabilities. Another, based on administrative records, finds that the top 1 percent owns more than 40 percent in that year.4

The estimates showing the concentration of income also underscore how hard it is to distinguish between capital, returns on capital, and accrued earnings from labor. Figure 1 assigns all employees’ wage earnings to “clearly labor.” But other categories of income are a mixture. For instance, business income can reflect some combination of returns to an owner’s capital investments and the labor of the owner. Further, the value of that business—which is a form of capital—may reflect both capital investments that have been made and the labor that has been invested. What’s more, if the business were sold, then the gain could be a combination of the returns on labor and capital because part of the business’s value may reflect the owner’s labor put into the firm. Finally, sophisticated high earners, especially those who mix labor with capital in the form of property, can sometimes convert labor income into capital gains.

It is notable that the effective tax rate on capital is relatively low in the United States, and its mobility across international boundaries can make it challenging to tax, even at current rates. For instance, the Congressional Budget Office calculates that, as of 2014, the effective marginal tax rate on new tangible investment in the United States stood at an average of 18 percent.5 This figure is likely a substantial overstatement of the tax rate on capital income broadly in the United States since it does not take into account the effects of international tax sheltering, especially with regard to intangible assets such as intellectual property. This mobility of global capital presents particular challenges to taxation. Owners of capital and especially corporate entities can, using tax planning techniques, report income as being sourced from low-tax foreign jurisdictions even when the income was in fact made in the United States. The recent spate of U.S. corporations moving residence abroad—either via “inversion” transactions in which they merge with smaller foreign corporations or via takeovers by larger foreign corporations—illustrates the challenge.6

Why tax capital

There is a long-standing debate as to whether to tax capital and the returns to capital. Some suggest that not taxing such returns—or at least the “ordinary” returns to capital that are broadly available to market participants—is optimal according to traditional economic models that trade-off between efficiency and equity. They argue for achieving a progressive tax system by focusing taxation on labor and “extraordinary” returns to capital (above market returns that are sometimes called “rents”)—the extraordinary returns on certain investments that derive from luck, market power, or other factors (such as returns on an early investment in the stock of Microsoft Corp.). But there are convincing arguments in favor of taxing capital and the returns to capital, and at rates higher than we do now. Taxing capital is an effective way—and perhaps the best way (in combination with other taxes)—of efficiently and fairly taxing the highest income earners in the United States.

This report largely focuses on the “how” of taxing capital, but first it’s important to summarize five leading arguments for why we should tax capital and at higher rates than now exist. Specifically, we should tax capital because:

- Taxing capital produces little effect on savings for high-income Americans

- There are compelling reasons to tax capital at higher rates than today once the

trade-off between efficiency and equity is fully considered - It is hard to distinguish between labor and capital income and, thus, failing to

tax capital can lead sophisticated parties to avoid taxation of labor earnings - It is better to use multiple tools to achieve progressive taxation, including taxing

capital, as a way of reducing “tax gaming” - Taxing capital is a highly progressive form of taxation

All of these reasons underpin the ultimate goal of higher capital taxation—to ensure federal tax revenues are sufficient to invest in the nation’s long-term economic growth. So let’s examine each of these arguments in turn.

Taxing capital produces little effect on savings

One of the main objections to taxing the ordinary return on capital is that it could discourage savings in addition to discouraging labor. Yet these “efficiency” effects have generally been found to be small. Underlying saving rates are not that sensitive to taxes, at least within the range of tax rates we have seen in the United States and probably especially for the wealthiest Americans. The economist Joel Slemrod at the University of Michigan divides responses to taxes among different categories—timing, avoidance, and real economic responses such as to labor supply or output.7 He and other economists find there are significant responses to taxes in the first two categories (timing and avoidance) but “no compelling evidence to date of real economic responses [in terms of labor supply and savings] to tax rates.”8

I have separately reviewed the literature of responses specifically to tax-preferenced retirement saving accounts,9 and while that literature has come to mixed results, a number of studies find positive effects of these accounts on saving.Those effects, however, seem to be most pronounced for those participating with low income and savings. The positive effects seem to be smaller for higher income and wealthier Americans; while they use the accounts, much of their saving appears to be largely substituted from saving they already would have done.10

In sum, taxing capital, especially of the wealthiest Americans, is a way of achieving highly progressive results but without much additional inefficiency relative to a tax that exempts the ordinary return on capital. Notably, many of the challenges to effectively taxing capital relate to the first two categories of behavioral response— timing and avoidance. Right now, there are too many opportunities in the current tax system to change the timing of taxation to the benefit of the owners of capital and sometimes for them to avoid tax entirely through tax-planning techniques.

There are compelling reasons to tax capital—and at higher rates than exist today—once the trade-off between efficiency and equity is fully considered

A number of economists conclude that taxing capital is optimal even when using traditional economic models that trade off efficiency and equity.11

The models that suggest otherwise—that the ordinary returns on capital should be spared from taxation—rely on a number of assumptions that are not reflective of reality. As Reed College economist Kimberly Clausing summarizes, these unrealistic models tend to assume “infinitely lived households, perfect foresight, perfect capital markets, and so on.”12 These same models also assume that ownership of capital is not a separate indicator of an ability to pay.

With more realistic assumptions, economic models suggest that taxing capital income is optimal—and often at rates higher than now exist. One set of economists take into account incomplete capital markets and both the life-cycle structure of labor and saving decisions and finds an optimal tax rate on capital of 36 percent.13 In another example, economists Piketty and Saez build a model that takes into account transfers of wealth across generations, imperfect capital markets, and shocks to the rate of return on capital, and conclude that optimal tax rate on capital income may in fact exceed that on labor income—which, in the United States, now faces a top tax rate above 40 percent, exceeding that normally imposed on capital.14

Because it is hard to distinguish between labor and capital income there is the opportunity for sophisticated parties to escape taxation on their labor if capital is not appropriately taxed

As noted above, it can be hard to distinguish between capital and labor income. As a result, failing to tax capital income—especially if done through mechanisms such as simply lowering capital gains tax rates—can lead to under-taxation of labor income. Further, this opportunity to reduce taxes by classifying income as a return on capital can generate substantial and wasteful tax planning.

The renowned carried interest loophole used often by private equity and venture capital fund managers—where the managers get taxed at capital gains rates on labor compensation paid to them in the form of a share of the investors’ profits—is but one example of ways in which tax planning can be used to report what is really a return on labor as a return on capital. The same is true of others whose labor services are mixed with property, such as the founders of a start-up company or developers of property. In each of these cases, there are opportunities for conversion between labor income and capital gains, as the returns on labor is reflected in the value of property that is eligible for capital gains. Thus, if the income from capital gains were to go entirely untaxed, then it would relieve taxes not just on capital but also on the labor earnings of taxpayers able to plan to convert their labor earnings into capital gains. This problem remains whenever there is significant deviation between the tax rate on capital and labor, as is the case today. There may not necessarily be a need to set the two rates the same since there are other trade-offs, but it is still a problem that develops and compounds as the rates deviate.15

It is better to use multiple tools—including taxing capital—to achieve progressive taxation, as a way to reduce “tax gaming”

Taxes can be avoided, of course, and, as noted above, these effects appear to be much more significant than changes in underlying labor-earning efforts and saving rates. Sophisticated taxpayers in particular will expend resources to avoid taxes. As law professor David Gamage at the University of California-Berkeley suggests, these very real effects of tax gaming give reason to deploy multiple tax tools so long as each one taxes according to ability and so long as each tool cannot be avoided using the same techniques. Or to put this more colloquially, sophisticated taxpayers may devote more resources more successfully to game the system when they only have to overcome one set of tax instruments and not multiple ones. This is an additional justification for taxing capital and not just relying on taxes focused on labor earnings and above-market rates of return on capital.16

Taxing capital is a highly progressive form of taxation

Taxing capital is highly progressive, whatever metric is used to measure progressivity. The ownership of capital and the income derived from it disproportionately benefits a relatively small share of the population—a population that has been gaining larger and larger shares of total economic resources in the United States.17 Thus, for policymakers concerned both with growing inequality and the federal government’s need for additional revenue to support key investments and programs, capital taxation is an important tool. Indeed, taxing capital is probably a first-best tool for achieving progressive taxation. But even if it is not, it is a significant lever to pull in the absence of other actions to increase revenue and enhance progressivity.

Importantly, empirical evidence suggests that taxes on capital tend to be paid by the owners of that capital as an economic matter—meaning that the owners of capital are not just the ones who send the check to the government but, for the most part, actually bear the economic burden of the tax. The alternative possibility is that the owners of capital shift activity and, in doing so, push the economic burden of the taxes onto labor rather than themselves. This view—that taxes on capital for the most part fall on capital—is perhaps most disputed when it comes to corporate taxation. That is because the entity-level tax is based on the “source” of the corporation’s income, and, thus, it can potentially be avoided by engaging in operations abroad rather than in the United States. That migration could theoretically lower returns to labor. Yet even when it comes to the corporate income tax, many analysts—including those at U.S. Department of the Treasury and the Congressional Budget Office—find that most of the tax is borne by owners of capital. After surveying the evidence, Treasury assumes that 82 percent of the corporate income tax is borne by capital and the rest by labor. The Congressional Budget Office assumes 75 percent is borne by capital.18

Why use multiple tools for taxing capital

This report suggests reforming multiple tax tools to better tax capital. Among those tools are individual-level income taxation through capital gains, entity-level taxation through the corporate income tax system, and wealth taxation largely through the estate-and-gift tax systems but also potentially through more regularly scheduled taxes on wealth. All of these tools fall largely on capital, but they are not interchangeable. The tools are all focused on capital but in different ways and at different stages. The differences among these tools have at least a few important implications.

First, some of these tools probably deserve to be deployed more than others relative to the current system. As will be discussed more below, there are strong arguments for taxing corporate income more at the shareholder level—through the individual level tax—and reducing some of the liability at the corporate level given the relative ability to game the U.S. corporate tax system. But it is important to note that such reforms may be limited by the very large share of corporate stock now held in nontaxable accounts (unless that too is reformed), as also discussed below.19

Second, some of these tools—and, in particular, taxes on transfers of wealth across generations—can be justified by a set of additional arguments to the ones offered above with regard to the taxation of capital more broadly. For instance, there may be an independent value of reducing dynastic wealth, and there are other fairness and efficiency arguments specific to inter-generational transfers.20

Third, there are good reasons to use multiple tools, with different structures, to tax capital. As Piketty and Saez argue, this can be justified in terms of traditional economic models, which, as they show, can justify both taxation of bequests and earlier taxation of capital income and wealth itself.21 But it is also justified by the types of tax avoidance that these models do not take into account. This is based on the same logic as one of the justifications offered above for taxing capital income in the first place—namely, that more tax tools are better than fewer tools in reducing tax avoidance.

Each of the main tools discussed in this report—taxation of gains on property, taxation at the corporate level, and wealth taxes—prompts tax planning to try to reduce the effects of these taxes. Taxpayers will try to adjust when to realize capital gains, where to report profits, and how to structure an estate or gifts to reduce their value. This kind of gaming justifies the use of multiple tools and not just taxing capital one way—so long as the tools cannot be gamed in the same way and so long as each correlates tax liability with people’s ability to pay.22 Using multiple tools should reduce total gaming by sophisticated taxpayers.

Reforming the realization of capital gains from the sale of property

Gains from the sale of property—or at least what is reported as gains from the sale of property —represent a significant share of total income for those at the top of the income distribution. Much of that is taxed at the preferential capital gains rate, with a current top rate of 23.8 percent. For the top 1 percent of income earners, capital gains comprised an average of more than 20 percent of their “market” income from 1992-2013, according to the Congressional Budget Office.23 The ratio is even higher when examining an even narrower band of the very tippy top of the income ladder. For instance, capital gains represented an average of 58 percent of the adjusted gross income of the top 400 income-earners in the country over that same period according to the U.S. Internal Revenue Service.24 (The IRS uses adjustable gross income, which is a somewhat narrower definition of income than the CBO’s use of market income.)

Gains on property would represent an even larger share of income for high earners since only some of those gains qualify as capital gains, with other gains on property taxed as ordinary income. Further, this measures only realized gains. Among certain very wealthy individuals, unrealized gains can compose almost the entirety of their economic income—that is, their income taking into account the unrealized appreciation on property.

Whatever the size of these gains, simply increasing the tax rate on them will not produce much additional revenue because the taxation of income from the sale of property is undermined by two related aspects of the tax system. First, these gains are taxed only when they are realized and recognized. The definition of realization is technical, but it often occurs when there is a sale of the property. Further, for the income to be included, the gain must be “recognized,” meaning that there is no special exception in the tax law allowing the realized gain to be further deferred.

This “realization/recognition” rule makes it relatively easy for a person with gains on property to defer paying tax on those gains. To do so, the person must simply avoid realization and hold onto the property (or take advantage of one of the non-recognition rules). Notably, property owners can borrow using the appreciated property as collateral and even borrow against the appreciation without realizing any gains. This makes deferral even easier.

Second, these gains are wiped out upon the death of the owner of the property. This is often called “step up in basis at death” or “step up” for short. The basis of the property—against which gains on property are measured—is set equal to the fair market value of the property at the time of an owner’s death. As a result, any gains earned over the life of the owner of that property are entirely eliminated; those inheriting the property do not have to pay any tax on the previously accrued gain. Should the inheritors sell the property shortly after inheriting it, they would pay tax only on the gains registered since the inheritance.

These two policies combine to form a key weakness in the U.S. income tax system. Taxation in the realization-based system is easy to avoid or defer—and deferral reduces the value of the tax to be paid due to the time value of money. Further, and very importantly, if any gains are deferred until death, then they get entirely wiped out. As a result, realization behavior is relatively sensitive to the tax rate; the higher is the tax rate, the greater the incentive to hold property and defer any gains—potentially until the point at which they are entirely eliminated.

Even a recent and widely cited success in raising taxes paid by the highest-income Americans illustrates the challenge. In 2013, tax rates for the highest-income Americans rose as parts of the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts expired and increases enacted in the Affordable Care Act came into place. For the top four hundred highest income taxpayers, this resulted in their effective tax rate rising from 16.7 percent to 22.9 percent.25 But there was also evidence of significant tax avoidance. For instance, net capital gains reported on tax returns fell by 20 percent from 2012 to 2013 (and despite 2013 being a banner year for the stock market), as high-income taxpayers shifted timing of realization to try to avoid the tax increase. This was a short-term timing effect, but similar planning can play out over the long-term.

There is relatively little additional revenue to be gained by further increasing capital gains rates without other reforms because raising the rate causes people to further defer capital gains. For instance, if there were no effect on the degree to which people defer gains, then a two percentage point increase in the capital gains and dividends tax rate would raise in the range $180 billion over ten years.26 By contrast, the official revenue estimators at the Joint Committee on Taxation estimate that a two-percentage point increase would raise only $50 billion.27 Further, they assume that the revenue-maximizing rate on capital gains is in the range of 28 percent to 32 percent—not much beyond this two percentage point increase on top of the current 23.8 percent top rate.28

Notably, this deferral does not just reduce revenue; it also reduces economic efficiency. This effect is known as “lock in”—as asset holders are “locked in” to their investments relative to what they would otherwise be. This means that people do not liquidate their investments when they might prefer to do so in the absence of tax effects, and assets are not necessarily held by those who would maximize returns on them on a pre-tax basis. Again, this is because the tax system essentially subsidizes those holding the assets to continue doing so—with the subsidy leading to behaviors that reduce economic productivity and growth, with little or no benefit associated with these tax-avoidance strategies. The bottom line is that, without significant reforms, the tax system cannot generate much in additional revenue through taxation of property transactions because it is simply too easy to avoid.

Fundamental Reforms

Several fundamental reforms could substantially reduce the incentive to defer the realization of gains on property. Most of these kinds of reforms involve some combination of a “mark-to-market” system and a charge for deferring such gains. A mark-to-market system would, on an annual basis, recognize any gains or losses on property. Such a system would fully eliminate any incentive to defer gains since there would no longer be any ability to do so.

But there are a few key challenges to establishing mark-to-market systems that have been widely cited. First, there is a problem of annually valuing properties that are not publicly traded or otherwise readily valued, which is often referred to as the valuation problem. Second, there is the problem of charging people taxes to be paid in cash when there was no sale of the property and cash may or not be available, which is known as the liquidity problem. Third, there is the psychological barrier to taxing people on what are often characterized as “paper gains and losses” because those gains or losses have not been realized or recognized by some kind of market transaction, such as a sale, which is known as the “paper-gain” problem.29

Some of these problems can be overcome by either combining a mark-to-market system with a charge for deferring gains or just using the deferral charge alone. In that case, those deferring gain are charged for the time value of money but are not made to pay tax on gains on an annual basis. This approach could help solve at least two of the challenges described above. First, the valuation problem could be overcome for assets that are not publicly traded or readily valued by paying a charge for deferring the tax payment, though this comes with certain other downsides. Second, the liquidity problem could be resolved by waiting until the disposition of assets to recognize gains.

However, while a deferral charge would reduce lock in and avoid some of the complications of mark-to-market, it would necessarily be “rough and ready”—and still lead to some distortions of when people chose to hold or sell properties. If the annual valuation of non-publicly traded assets were to be avoided—a key attraction to this style of system—then the charge for the deferral could not reflect the exact path of any gains. Correctly charging for the deferral of gains would require knowing exactly when the gains were made, but if there were no annual valuation then any system for making those charges would have to roughly approximate the charges. So such a system would still produce circumstances where the tax system would encourage deferral (and, in fact, circumstances where it also encourages the realization of gains), but the distortions relative to the current system should still be smaller.30

Tax experts have offered a number of possible models combining mark-to-market and deferral charges. Here are just two examples of promising systems.

Mark-to-market on publicly traded assets plus a deferral charge for other assets

This style of system is the brainchild of tax lawyer David Miller at the law firm Proskauer Rose.31 Miller recommends applying this only to the most wealthy Americans and largest businesses. For these people and entities, the system would require mark-to-market accounting for publicly traded assets, with tax paid on them on an annual basis. There would then be a deferral charge for other assets to be paid at the point of disposition of the assets—just like under the current system but with an additional charge based on length of holding.32 Such a system would significantly reduce the problem of deferral and would not generate significant challenges in terms of valuation.

Furthermore, the wealthiest Americans and largest businesses would be unlikely to face liquidity constraints and so would be able to pay taxes in cash when the gains had not yet been converted. The problem with this system, however, is in this very limitation to a very select group of taxpayers. The reason: A threshold such as this could create opportunities for gaming the system and generate perverse economic incentives to try to avoid falling within the ambit of this system. Miller suggests phasing the system in based on a combination of annual income and wealth in order to address this problem, but some incentives to game the system would remain.

Deferred tax accounting

The Ohio State Law professor Ari Glogower recommends a system that would fully marry mark-to-market accounting with a charge for deferring capital gains.33 In this system, no tax would have to be paid until there was a realization event, as in the current system, but there would be a deferral charge applied to the sale of assets at that point.34 For assets that are publicly traded or readily valued, the deferral charge would be based on the specific path by which the gains accrued. For instance, if the gain had mostly occurred early on in the holding of the asset, then the deferral charge would be larger than if the gain occurred mostly toward the end of the holding period—since more deferral would have occurred in that case.

For other assets that could not be so easily valued, the system would assume a constant rate of accrual over the period in which the asset was held as a type of “rough and ready” deferral charge. This would have many of the benefits of full mark-to-market accounting but would largely address the valuation and liquidity problems that could plague full mark-to-market accounting. Such a system could also apply more broadly than one that still included mark-to-market accounting, even only for publicly traded assets since there would not be same problem with liquidity for those who are not at the very top of the wealth distribution.

But one argument against these more fundamental reforms is that these systems would tax not just real economic gain but also inflationary gain—the gain due to rising prices that do not reflect an actual increase in the real value of the property. The current system also taxes inflationary gain, but those gains are more than offset by the aspects of the current system that provide relief—especially the allowance of deferral, which these fundamental reforms would eliminate. In an environment of low and relatively predictable inflation, the problem of taxing inflationary gain is not as large as it otherwise would be. In fact, as a “rough-and-ready” adjustment, rates could be set lower than they otherwise would be, taking into account that a portion of gain would be due to inflation.

There could be other, more exact ways to take inflation into account when calculating capital gains in these two types of mark-to-market and deferral-charge systems. For instance, taxpayers could elect to index their capital gains to inflation to create a reformed tax system that responds to changed conditions such as an unexpected increase in the rate of inflation. There is no good reason to tax inflationary gain in a reformed system if administrable alternatives are available.

Revenue potential of reforms

These more fundamental reforms to the realization system could produce considerable revenue. For instance, a mark-to-market system on corporate equities alone—with the capital gains plus dividends taxed as ordinary income—has been estimated to raise more than $1 trillion over a decade.35

Intermediate steps

Fundamental tax reform of the capital gains tax could prove to be a difficult policy lift in Washington. An important, intermediate step to reforming the taxation of property transactions is to tax unrealized gains on property when that property is transferred in the form of either gifts or bequests. The wipeout of gains at death would no longer occur, which would have two key effects. First, there would be less incentive to defer any gains before that point. Without the prospect of a wipeout in gains at death, holders of property would be more willing to realize gains earlier. Second, even if property were held until death, the gains would not escape taxation.

Given the reduction in the incentive to defer gains and the taxation of accrued gains at death, raising the tax rate could generate considerably more revenue. The ability to raise significant additional revenue via rate increases is entirely dependent on reforms that reduce the ability to avoid taxation through deferral. The Obama administration proposed a version of this reform. Under the proposal, transfers of appreciated property in the form of gifts or bequests would trigger taxation, but with targeted exemptions. The first $100,000 in gains recognized because of the death of the owner would be exempt, as would any gain on personal property other than collectibles. The administration then combined this proposal with a 4.2 percentage point increase in the tax rate on capital gains and dividends, raising the top rate to 28 percent.36

Altogether, the proposal is estimated by the Joint Committee on Taxation to raise nearly $250 billion over the next ten years, with revenue increasing from then on as the policy fully phases in.37 Notably, the administration proposal retains the current law treatment of property donated to charity, which exempts such property from taxation while providing a charitable deduction equal to the full fair market value. The reform of charitable deductions goes beyond the bounds of this report, but if that “double benefit” for the donation of appreciated property were limited or eliminated, then the revenue raised would be considerably larger.

One key challenge with taxing these gains when they are transferred via gift or bequest is that there is not an arm’s-length sale to establish the fair market value. This poses significant administrative challenges when it comes to assets that are not publicly traded or readily valued, which compose roughly half of the wealth of Americans with assets greater than $2 million.38 Yet this challenge could be partly addressed because the current tax system already requires the valuation of transfers of large amounts of wealth by gift or bequest for purposes of estate and gift taxes. Thus, those already subject to estate and gift taxation would not require another round of valuation; the same valuation used for estate and gift tax purposes could be used to calculate the amount of gain on the property.

Importantly, if a proposal such as this were adopted, the revenue-maximizing capital gains rate should rise because there would be no ability to avoid the tax by simply holding property and wiping out the gain upon bequest. There have not been estimates made of the degree to which this is the case, but it seems likely that taxing appreciated gain upon gift or bequest would make realizations less sensitive to the tax rate.

Reforming corporate taxation

The U.S. corporate income tax is a significant source of revenue for the federal government—generating revenue equal to about 2 percent of GDP or roughly 10 percent of total revenues.39 Who actually bears the tax as an economic matter is controversial. Still, analysts at the Congressional Budget Office, the U.S. Department of the Treasury, and others conclude that the substantial majority of the tax burden falls on capital (those who own corporate stocks) and not labor (employees and consumers).40

The corporate income tax is increasingly being undermined, however, by two inter-related challenges that allow some of the largest multinational corporations to escape taxation. These challenges are:

- Manipulation of the source of income by corporations

- Manipulation of corporate residence by corporations

Let’s examine in turn each of these challenges to the U.S. corporate income tax.

Manipulation of the source of income by corporations

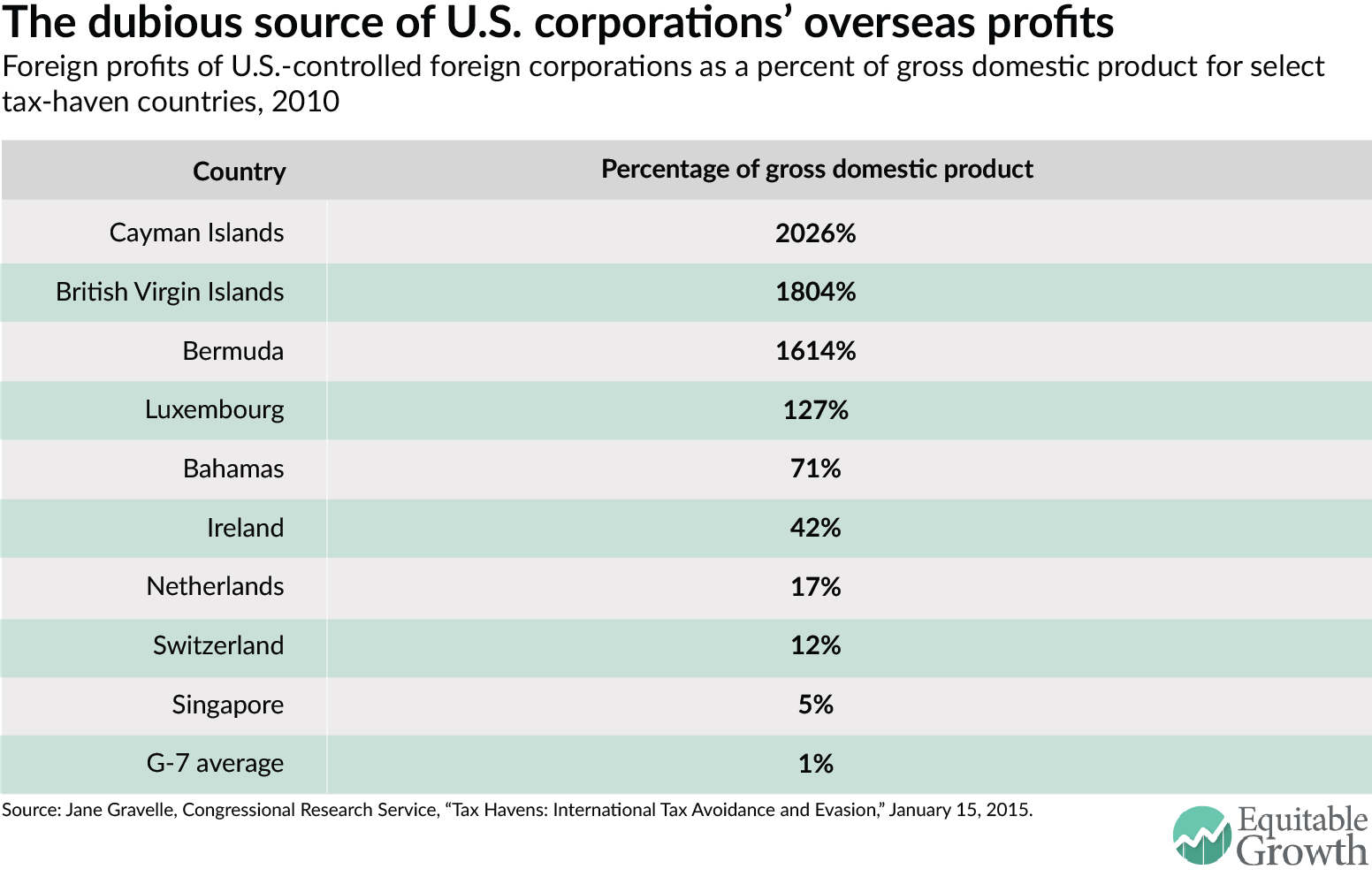

The amount of taxes that a corporation pays to the U.S. government depends in part on the “source” of those profits—that is, where the service or product was generated creating those profits. However, the reported source of profits is easily manipulated, especially by sophisticated multinational corporations. More than half of foreign profits reported by U.S. corporations are from tax-haven countries such as small Caribbean islands, tiny Luxembourg, and the more familiar offshore financial centers of Bermuda, Switzerland, and Singapore, according to recent research by University of California-Berkeley economist Gabriel Zucman.41 The profits reported are, in a number of cases, many multiples of these countries’ GDP—and, in all cases, well above the average of U.S. corporation’s foreign profits as a share of GDP in the Group of 7 industrialized democracies. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

Table 1 shows the perversity and absurdity of this corporate tax dodge. Reported foreign profits by U.S. corporations in Bermuda, for instance, are sixteen times the size of the country’s economy.

Reed College economist Kimberly Clausing estimates that the amount of revenue loss by the federal government from such profit shifting was between $77 and $111 billion per year as of 2012—or between 35 percent and 46 percent of actual corporate tax revenues collected by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service. This is up considerably from just 2004, where such profit shifting is estimated to have lost revenue equivalent to between 16 percent and 23 percent of actual collections according to Clausing.42 Zucman’s findings are similar.43

There are two main methods that corporations are using to shift these profits. One is transfer pricing, and the other is earnings stripping. Here’s how both maneuvers work.

Transfer pricing

Multinational corporations are generally composed of different subsidiary corporations and other related entities. The current U.S. corporate system respects the boundaries among these related entities and then asks corporation to determine how much in profits are “sourced” from U.S.-based entities. The rules require that, for tax purposes, these various related entities treat the transactions among themselves as if they were with an unrelated third party—the so called “arms-length” principle—so that the source of profits can be properly determined.

The problem with this principle is that these entities are not in fact unrelated. That means the pricing of these transactions can be manipulated, despite the very transfer-pricing rules meant to stop such abuse. Property—especially intellectual property—developed in the United States gets sold to a related entity based in a low-tax country at a fire-sale price, leading to low profits in the United States and high profits abroad. Manipulation is particularly easy when it comes to intellectual property, since it is hard for the Internal Revenue Service to challenge the corporation’s valuation of these kinds of properties, such as patents and trademarks. The result is that U.S. corporations—especially ones with any significant intellectual property—can manipulate transfer pricing to shift much of their profitability overseas.

Earnings Stripping

Multinational corporations—especially ones with a foreign parent—can strip profits out of the United States by, among other mechanisms, manipulating the debt burdens of the U.S. subsidiary versus the rest of the company. A foreign-based multinational corporation, for instance, can load up its U.S. subsidiary with

debt owed to another part of the same company in a low-tax jurisdiction and then take a deduction for the interest against its U.S. profits. The interest is then taxed abroad in the low-tax country. This maneuver enables profits derived from a multinational company’s U.S. investment and its workforce to be reported overseas. Foreign-based multinational corporations with U.S.-based subsidiaries also can strip profits by paying royalties and other fees back to the parent corporation. Importantly, the same maneuver cannot be done as easily by a multinational with a U.S. parent—though U.S.-based companies can do this in other high-tax countries.

As a result, profits made in the United States get shipped overseas to tax havens, often in the form of interest, and this puts foreign-based corporations at an advantage operating in the United States because they can more easily engage in these maneuvers than U.S.-based corporations under current tax rules. This, in turn, puts substantial pressure on U.S. corporations to manipulate their “residence” in the United States and, in part, motivates so-called corporate inversions and foreign takeovers. The issue of corporate residence is taken up in the next section.

Manipulation of residence by corporations

The tax treatment of corporations in the United States is based in part on the “residence” of the corporation, and residence is also adjustable. U.S.-resident corporations, for example, are sometimes subject to tax on foreign profits, but when it comes to profits of “active” business operations—as opposed to “passive” income (such as interest and dividends) from investments—that tax only applies when those profits are eventually repatriated. U.S. corporations today boast more than $2 trillion in un-repatriated profits,44 and some are changing their residence to foreign countries in order to gain access to these profits without ever paying tax in the United States.

Another example of how residence matters is in terms of a corporation’s ability to strip profits out of the United States using intra-company debt. As discussed above, that is much easier for a foreign-based multinational corporation than one based in the United States.

The result of this pressure on residence is a spate of transactions to move the residence of U.S. corporations abroad, driven in part by a desire to reduce U.S. corporate taxes. Some of these transactions are in the form of more egregious “inversions” in which U.S. corporations merge with smaller foreign partners in order to establish residence abroad. Others are in the form of more traditional takeovers by larger foreign corporations.

Shifting of real economic activity

Such gaming of the U.S. corporate tax system—often involving purely paper transactions—is the central challenge facing the corporate income tax, but the movement of actual economic activity is also an attendant concern. Among other issues, in a source-based tax system, corporations may choose to source real economic activity in lower-tax jurisdictions. This generates inefficiency because the investment decisions are being, in part, driven by differences in the tax rate rather than where the investments would be most productive.

What’s more, such manipulation can shift the collection of the U.S. corporate tax away from capital toward labor—to the degree that capital can escape taxation by shifting the location of the investment and leaving labor, which is relatively immobile, to pay more of the tax. In that case, the owners of the corporation essentially escape at least some of the economic burden of the tax, and labor pays more of the burden, since labor would be less productive with some capital having flowed out of the country.

In the current system, evidence suggests that there are not substantial shifts in the location of corporate investments due to the corporate tax. As Clausing summarizes, “there is not a clear robust relationship between corporate tax policy variables and investment levels or the resulting capital stocks across OECD countries over the previous 30 years.”45 Yet it is possible that at least some of this lack of sensitivity in corporations’ investment decisions reflects the ease with which multinational corporations game the corporate tax system precisely because they are able to separate the tax rate from the location of their economic activity.46 So, such shifts in economic activity remain a concern, perhaps especially in a reformed corporate tax system that would make gaming harder to do.

International cooperation

Importantly addressing the problems facing the U.S. corporate income tax would benefit greatly from international cooperation to help avoid both the non-taxation of profits and double (or more than that) taxation of profits across different national tax jurisdictions. Recently, the OECD undertook a significant project on “base erosion and profits shifting,” and made a number of recommendations to try to improve how countries measure the source of corporate profits while maintaining the same basic structure as now exists.47 Some of these recommendations are reflected in the intermediate steps discussed below, such as cracking down on the ways in which corporations use intra-company debt and transfers of intangibles to shift profits. But cooperation along these lines cannot overcome some of the fundamental weaknesses of the current approach—the source of profits could still be manipulated since transfer pricing among related entities would still undergird the system.

Fundamental reforms

The United States should be pursuing fundamental reforms to reduce corporate tax avoidance and economic distortions. There are at least two fundamental steps that could be taken to substantially strengthen the corporate tax system:

- Switching from source-based to destination-based corporate taxation

- Putting more of the corporate tax burden on shareholders rather than corporations

These two fundamental reforms are detailed below.

Switch from source-based to destination-based corporate taxation

Switching from taxing the “source” of the activity generating corporate profits to the “destination” of the products or services generating the profits would reduce or eliminate the ability to cut a corporation’s tax bill by manipulating the source of profits, shifting the residence of the corporation, or the location of real economic activity.

Leading proposals in this regard often involve systems of “formulary” apportionment that rely mostly on where the corporation makes its sales.48 Specifically, related entities across a corporation, both in the United States and abroad would be treated as a single financial unit, with combined reporting of profits. The profits would then be divided among countries based on a formula that emphasizes the share of sales in each country (but could also include items such as the share of workforce in each country). In the vision of most proponents of formulary apportionment, the United States would tax only the profits allocated to the United States based on this formula.

The idea here is that sales would be harder for corporations to manipulate than the prices that related corporate entities charge each other. Other factors could potentially be taken into account in the formula—such as payroll or assets—but there is reason to think that the location of sales would tend to be less sensitive to tax than these other economic activities.49 In such a reformed system, if a U.S. corporation had shifted its key intellectual property to an Irish subsidiary at a fire-sale price then it would no longer matter—to the extent the corporation’s sales were in the United States so would be taxes on its profits under the system. The current “source” rules would be retired.

This system is akin to the one that U.S. states use successfully to allocate profits for purposes of state-level corporate income taxes. The states rely on formulas that weight some combination of the location of payroll, assets, and sales of the corporation—with states increasingly emphasizing sales. Evidence suggests that there has been relatively little shift in economic activity as a result of state use of these formulas.50 This finding is bolstered by the experience of the Canadian territories where there appear to be less in the way of profit shifting among those companies subject to formula-based allocation of profits (using payroll and sales) as opposed to source-based allocation (like the current U.S. international system).51

The apportionment of corporate sales for tax purposes, however, is not without its own downsides. Sales, too, can be manipulated,52 and tax incentives for such manipulation in the federal system would be much larger than in the U.S. states since rate differentials would be greater. For instance, products could be cycled through low-tax countries. Apple Inc. could build its iPhone in the countries where it currently manufactures them, sell the completed product to an unrelated distributor in a low-tax country, and then the distributor could sell to the United States. In this way, Apple would largely avoid U.S. taxation of its profits since its sales would only go to the low-tax country.

Anti-abuse provisions would be needed to stop such transactions. Even so, there could be successful planning that would be hard to stop with anti-abuse provisions. Returning to the Apple example: Imagine Apple licensing the design for an iPhone to other, unrelated companies in low-tax jurisdictions to produce and sell the device. Apple’s high-margin activity of developing the design might escape taxation in the United States, and it could be challenging to stop with anti-abuse provisions. With that said, formulary apportionment would probably be more difficult to manipulate than transfer-pricing rules. A licensing transaction such as the one imagined for Apple would require completely redoing its highly successful business structure, which it very well might not do. In contrast, transfer-pricing games only require a well-paid accountant manipulating often paper-transactions among related entities.

There are other approaches to implementing “destination-based” corporate taxes that deserve serious consideration. For instance, public finance and economics professor Alan Auerbach at the University of California-Berkeley suggests a system in which the foreign transactions of U.S.-based corporations are simply ignored for tax purposes, but there would then be a tax imposed on imports into the country as part of a a so-called border-adjustment system.53 Auerbach grafts this system onto a larger reform that would shift the corporate system to only taxing above-market returns on investment—the extraordinary returns that pay more than that normally available in the market—and not on ordinary returns (the normal returns available in the market). His proposal would do this by allowing for the full expensing of capital investment; the immediate write off of capital investment then would limit the corporate tax to taxing these extraordinary returns. Auerbach’s destination-based international reform, however, could potentially be done separate from allowing the full expensing of capital investments.

Auerbach suggests this style of reform would be less open to manipulation and less distortive than a formulary apportionment approach. This is because his proposed tax system could not be gamed, for instance, by routing sales through foreign distributors or even rearranging licensing arrangements like in the Apple example above, so long as there is a border-adjustment tax on imports.

The point is that the corporate tax code could be substantially improved by switching to a destination-based system. It would eliminate the current “arms-length” source rules that have proven so problematic. And there are several methods for doing so, each of which would be a significant improvement over the existing structure. Importantly, any such switch would interact with existing treaties, including both tax and trade treaties. These interactions are complex, and scholars differ on the degree to which such fundamental reforms would require renegotiating these treaties.54

Put more of the tax burden on shareholders rather than corporations

Effectively taxing capital in large part comes down to trying to tax it in ways that are less susceptible to tax planning and gaming than the current system. The current U.S. corporate income tax system is gameable in large part because it puts so much pressure on the source of profits and the residence of corporations. The reforms discussed above would be significant improvements across both of these dimensions. But in some cases, the corporate tax would remain susceptible to planning and gaming. For instance, formulary apportionment would be better than the current source rules yet sales too can be gamed. And, if the residence of corporations remains a significant factor in corporate taxes then that too can be manipulated—even if the rules are strengthened.

This provides reason to move more of the burden of capital taxation directly onto shareholders and other owners of property and away from the corporate entity itself. In the United States, the individual level tax is based largely on the citizenship of the person—not the location of the profits that they make or the residence of the entities that they own. And the citizenship of people—for a large country such as the United States—is probably not all that sensitive to taxes relative to corporate residence and profits because renouncing citizenship involves potentially having to move countries, and the United States has an exit tax on accrued gains for those leaving. Importantly, it is also becoming much more challenging for U.S. citizens to try to evade tax using foreign accounts given a new law that requires reporting from foreign financial institutions.55

There are several methods for shifting more of the tax burden onto individuals from the corporate entity. One attractive approach is using the corporate entity to tax only the extraordinary returns to investment—the above-market returns that come from luck, market power, or other factors. A recent paper sponsored by the International Monetary Fund and by leading tax scholars recently set out the case for focusing the corporate tax on these rents, which they argued that the corporate tax could more effectively tax—while ordinary returns to capital would be taxed at the individual level.56 A reform such as this could be done in a number of ways, including the expensing regime discussed above. Another approach to shifting the tax burden is to simply reduce the corporate tax rate—reducing the tax rate on both ordinary and extraordinary returns at the corporate level.

Still, there are several barriers to shifting the corporate tax burden to shareholders.

First, there is a question of how to actually get shareholders to pay more in taxes than they do now. Simply increasing capital gains and dividends rates will not generate much in revenue due to the realization rule on property. (See pages 18-22 of this report for details.) So a strategy of shifting the tax burden probably should involve combining this new system with a fundamental reform of capital gains taxation, either mark-to-market taxation or a deferral charge, and using part of the revenue to finance either focusing the corporate tax system only on extraordinary returns to investment or reducing the corporate tax rate. Reforms such as this—combining reductions in the corporate income tax with fundamental reform of taxation at the shareholder level to increase their taxes—have recently been suggested by Eric Toder at the Urban Institute and Alan Viard and the American Enterprise Institute as well as by Harry Grubert at the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Tax Analysis and Rosanne Altshuler at Rutgers University.57 The proposals they put forward are designed to be revenue-neutral, but there is no reason that they could not be designed to be revenue-enhancing.

Second, there is the issue of the amount of revenue that could be generated at the shareholder level even with reformed capital gains taxation. Even moving to a full mark-to-market system on publicly-traded corporate stock—and taxing the gains at ordinary income rates—would not generate anywhere near enough revenue to fully replace the U.S. corporate income tax system. Estimates suggest that doing so would replace well under half the revenue generated by the corporate income tax.58

One reason: Significant shares of U.S. corporate stock are held by people and entities that are not taxable at the shareholder level—for instance, foreign shareholders, pension funds, and U.S. individuals through retirement accounts. In fact, very recent evidence indicates that the share of corporate stock that is not subject to tax may be considerably higher than previously recognized—around 75 percent according to the most recent estimates.59 Any proposal to shift the tax burden from the corporate level to the shareholder level must address this challenge. And some of the recent proposals do. For instance, Viard and Toder—in the latest version of their proposal—would impose a tax on the equity and dividend income of retirement plans and non-profits (entities that, up to this point, had not been directly taxable).60

Revenue potential of reforms

These fundamental reforms have the potential to generate significant additional revenue. And, they do so more efficiently than the current system and with greater confidence that the burden really will fall on the owners of capital. Auerbach, for instance, suggests that his proposed reform—to shift to a destination-based system while only taxing extraordinary returns at the corporate level—would have a small net impact on revenue, and potentially a positive one.61 The proposal could raise more revenue if either the plan were changed to continue to tax the ordinary return to investment at the corporate level or, alternatively (and probably better), the proposal were combined with fundamental reform at the individual level to better tax returns to capital there.

Similarly, a number of the other fundamental reform proposals discussed here have been designed to be revenue-neutral, as a way to focus on the improvements in administration and efficiency. But changing their parameters could make them revenue-enhancing.

The revenue at issue is likely to be significant. Revenue-enhancing versions of these reforms could potentially generate many hundreds of billions of additional revenue over the next ten years—and, again, more efficiently and fairly than we do now.

Intermediate steps

Some intermediate steps would involve keeping the same basic structure of the U.S. corporate income tax as we have now but making both source-based and residence-based criteria harder to manipulate for corporations, and to make those factors matter less than they now do.

Such steps would include a number that have recently been at the center of the tax debates in Washington. Among them:

- Increase the effective tax rate on foreign profits of U.S.-based corporations

- Crack down on ways that corporations shift their “source” of profits, including

ways most easily available to foreign corporations - Making it harder for U.S. corporations to shift residency abroad

Let’s examine each of these steps in turn.

Increase the effective tax rate on foreign profits of U.S.-based corporations

The current U.S. corporate tax system allows for deferring the payment of taxes on active foreign profits, which puts significant pressure on the “source” rules. Even though taxation on those foreign profits in the United States would—in theory—eventually be imposed, corporations seem to treat deferral as a significant tax benefit. They may have never intended to repatriate their foreign profits or they may believe that the tax rate on repatriated profits will eventually be lower than it is today. Whatever the case, the ability to defer paying taxes on foreign profits incentivizes corporations to try to shift profits out of the United States to take advantage of deferral.

One way to defend against such profit shifting by U.S. corporations is to tax the foreign profits of the corporations at a higher rate than is now effectively imposed through the deferral system.

The Obama Administration proposed a minimum tax on foreign profits of U.S. multinational corporations, taxing them at less than the U.S. tax rate but still higher than they are now effectively paying. Specifically, the proposed tax would be a 19 percent minimum tax imposed on a per country basis and without any deferral.62 This tax reform is estimated to raise nearly $300 billion over the next decade.63

A key challenge, though, is that the more corporate taxes are imposed on the foreign profits of U.S.-based corporations, the greater the pressure is on “residency.” The minimum tax could be avoided entirely if corporations were not U.S.-based. Measures could be taken to make residence less open to manipulation by multinational corporations, but those measures are by no means full-proof, and residence will remain, to a significant degree, adjustable by corporations. The United States probably boasts more “market power” when it comes to the decisions made by corporations on their residencies, which allows the federal government to impose greater taxes on foreign profits than other nations. But there is a trade-off here—a trade-off that some of the fundamental reforms discussed above overcome by switching to a destination based tax system where residency is far less important.

This trade-off raises the important question of how much to increase the tax rate on foreign profits. Due to the effect on corporate residence, unless the U.S. corporate tax rate is lowered very substantially (which is costly and so challenging to do in a way that does not undercut the federal government’s overall revenue base), there should probably remain a gap between the tax rate on profits made in the United States and those made abroad. There are serious proposals to tax domestic and foreign profits of U.S. corporations at the same rate and on a consolidated basis, but these generally assume a large reduction in the corporate rate.64

Crack down on ways that corporations shift the “source” of profits

The first reform would reduce the importance of source—since it would tax foreign-source profits of U.S. corporations more like U.S.-source profits. Nonetheless, source would still matter. It would matter for U.S. corporations because the tax rate on foreign profits would remain below that in the United States under a minimum tax, and it would matter for foreign-based corporations because profits booked outside the United States would go untaxed here. Thus, the incentive for corporations to manipulate source would remain.

There are ways to improve source-based corporate taxation rules incrementally and perhaps especially when it comes to intangible assets and earnings stripping via interest deductions, which are key points of weakness. For instance, the source rules could be adjusted so that where a U.S. entity transfers an intangible asset to a related foreign one in a low-tax jurisdiction, the profits derived from that asset would not escape taxation in the United States if, based on later performance, it appears that the asset was sold at a fire-sale price to the foreign subsidiary. Specifically, any “excess profits” on the intangible asset—defined as profits in excess of costs associated with the intangible asset increased by a mark-up—could be subject to immediate taxation in the United States.65

This reform would essentially be a backup to the current “arms-length” standard, which allows the IRS to pursue transactions retrospectively based on actual performance. Another alternative is to switch to formulary apportionment of profits (see pages 30-31 above) but on a targeted basis, such as by targeting intellectual property specifically. The current corporate tax system is proving particularly inadequate in this regard.

The source-based corporate tax rule also could be adjusted to target the current advantage that foreign-based corporations have in reducing tax on U.S. operations vis-à-vis U.S.-based corporations. This kind of corporate tax reform would stem manipulation of both the source- and residence-based rules, since a key reason that U.S. corporations seek to move residence abroad through inversions or foreign takeovers is to be able to “strip” income out of the United States in ways that U.S.-based corporations cannot. Specifically, multinational corporations could be disallowed from taking interest deductions stemming from disproportionate debt levels at their U.S. entities relative to their whole corporate family.66 The Treasury Department has now proposed a rule that would try to address this problem via regulatory authority.67

Together, measures such as these would be important steps in improving the current “source” rules. Estimates of the Obama Administration’s corporate tax reform proposals along these lines—addressing excess profits from profits derived from intellectual property booked abroad and from earnings stripping—suggest that the federal government could raise more than $90 billion over the next decade.68 Still, even with these protections, the source-based tax rules would remain a deep weakness of the current system, which is why more fundamental reforms are needed.

Making it harder for U.S. corporations to shift residency abroad

The United States also could make it harder for U.S. corporations to shift residency abroad. For instance, the Obama Administration suggests making it harder to move residency abroad by requiring that, to do so, a U.S.-based corporation must merge with a larger foreign partner.69 Estimates suggest that this would raise more than $15 billion over the next decade.70

The United States could go beyond this, for instance, by adopting a so called management-and-control test, whereby corporate residency would be determined by where the merger occurred rather than place of incorporation. A management-and-control test, however, comes with the downside of potentially generating actual shifts in management and control abroad to avoid U.S. corporate residency. In short, there are ways to strengthen the concept of residency, but, even with such incremental steps, it would remain another weakness of the corporate tax code without more fundamental reforms.

Revenue potential of reforms

The Obama Administration has proposed a package of international tax reforms incorporating proposals like those discussed above and estimates suggest that they will raise more than $400 billion over the next decade, excluding the one-time revenue from taxing un-repatriated earnings.71 Including that one-time revenue, the revenue raised reaches over $600 billion.72 The Administration, however, envisions enacting this full package of measures as part of a reform that would also reduce the U.S. corporate tax rate. While a reform of this model has the potential to significantly improve the U.S. corporate income tax system and raise revenue, it would not fully alleviate some of the fundamental weaknesses of source and residence based taxation like the more fundamental measures discussed above.

Reforming wealth taxation

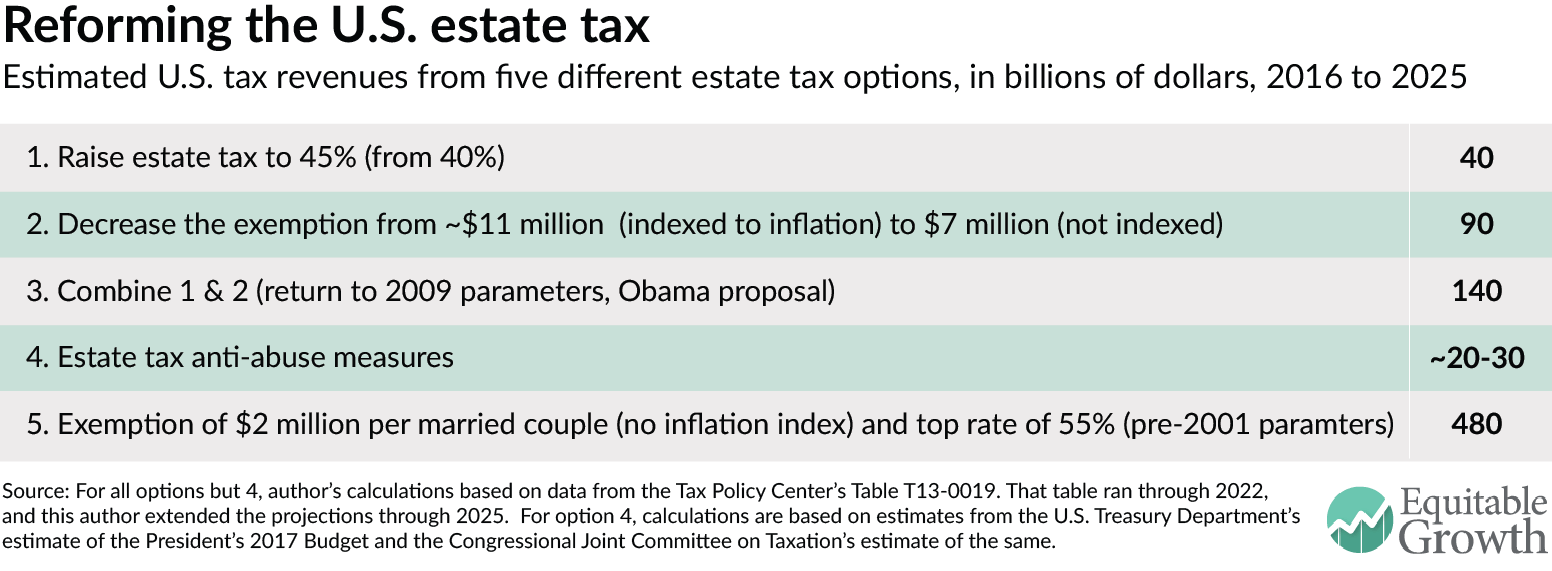

The federal government levies very limited taxes that apply to wealth—defined in this paper as the stock of capital—as opposed to income, which is the increased value of that capital over time. Specifically, the federal government taxes transfers of wealth via gift or bequest, but that applies to only a sliver of estates and gifts—and tax planning can relatively easily reduce total tax liabilities for the wealthy.

The exemption for estate-and-gift taxes now stands at just under $11 million per married couple, and its rate is 40 percent. Historically, this represents a substantial pullback in estate-and-gift taxes. Before the tax cuts enacted during the George W. Bush Administration in 2001, estate and gift taxes were scheduled to have an exemption of $2 million per couple and a top rate of 55 percent. After those estate-and-gift tax cuts, the tax now applies to less than 0.2 percent of estates—down from 2 percent of estates in the mid-1990s.73 Further, estate-and-gift taxes raise only about $20 billion per year, or about 0.1 percent of GDP, down from as much as 0.3 percent of GDP in the late 1990s and early 2000s.74

Estate-and-gift taxes are not only small relative to the past. They are also small relative to wealth. This can be seen in terms of the size of estate tax liability relative to estates for those subject to the estate tax—using valuations as reported to the IRS. For the very small number of estates subject to the estate tax, the tax represents only about 17 percent of the total estate, on average.75

This ratio is likely a significant overstatement, since estate and gift taxes probably undervalue wealth. One study by the IRS found that valuations for estate tax purposes are roughly half that of the Forbes 400, comparing those listed on the Forbes 400 to their estates after they died.76 Of course, it is possible that Forbes over-estimated the wealth of those listed. Yet according to the IRS some significant share of this discrepancy in declared wealth is probably due to tax-planning techniques, including the use of special “valuation discounts” and trusts.77 This suggests that estate and gift taxes are not capturing the full value of wealth being transferred—and is certainly not capturing it once every generation.

University of California-Berkeley economists Saez and Zucman estimate that the top 0.1 percent of wealth holders in the country—with wealth in excess of $20 million each—held roughly $11 trillion in wealth as of 2012.78 An estate-and-gift tax generating $20 billion per year represents less than 0.2 percent of that amount. In sum, the current estate-and-gift tax is a narrow wealth tax that raises less than it used to, is easily avoided with tax-planning techniques, and is small relative to both total wealth and wealth being transferred.

Fundamental reforms

There are at least two routes for fundamentally reforming federal wealth taxes. The first is to keep a system focused on transfers of wealth but switch the payer from the estate to the person actually receiving the inheritance—an actual inheritance tax. The second is a broader wealth tax applied on a regular basis, which would be a much more significant reform.

Inheritance taxation

An inheritance tax would change who pays transfer taxes on wealth. Instead of the tax being paid by the estate, it would be paid by the recipient. The change would not just be in terms of who literally sends the funds to the federal government. A reform recommended by Lily Batchelder, a professor of law and public policy at the New York University School of Law, comes with a number of innovations.79 First of all, her proposed inheritance tax would take into account the economic status of the recipients, which may be seen as fairer than applying the tax on a per-estate basis. As a result, the exemption would apply per recipient—so if an estate were divided among many heirs, there would be a lower tax bill than the alternative.

Further, under her proposal, the tax rate for a recipient would depend in part on the amount of income from other sources. And yet another benefit of her approach is that the tax applies as transfers are received, which means that trusts would no longer be as effective at avoiding taxation because the transfers from the trust would taxed as they are received by the heirs. There would no longer be a challenge of valuing trust interests at the time they are created—a valuation challenge that sophisticated planners use in gaming the system.

The inheritance tax has very real benefits in terms of fairness and administration, yet the overall incidence of heirs paying the tax is unlikely to be dramatically different from the current estate-and-gift tax system. Generating more revenue from the tax will come down to asking many of the same beneficiaries of transfers of wealth to effectively pay more than they do currently. These reforms may be a more elegant solution for a number of reasons, but it does not fundamentally change that dynamic in terms of revenue for the federal government. Thus, reforms of this variety are likely to raise amounts that measure in the several hundred billions of dollars—not all that different (in terms of pure revenue generation) from the intermediate reforms discussed below.

Wealth taxation

A more dramatic change to taxing wealth would be a tax on wealth that is regularly applied, such as the one suggested by economists such as Thomas Piketty at the Paris School of Economics, and University of California-Berkeley’s Saez, and Zucman. In their “Theory of Optimal Taxation,” Piketty and Saez describe why it would be optimal—using models focused on efficiency and equity—to combine annual taxes on wealth with inheritance taxation, rather than using inheritance taxation alone.80

These scholars also emphasize the potential administrative benefits, especially if the wealth tax were coordinated on a worldwide basis. For instance, Zucman describes the possibility of a small worldwide withholding tax on all wealth that would be administered at the “source,” meaning it would be administered by specific financial institutions holding the wealth of individuals. A refund would then be available from a national government if the owners of the wealth revealed themselves—and thus became subject to the country’s other tax instruments, such as income taxes and inheritance taxes.81

Another administrative benefit of wealth taxation at regular intervals is that it may be harder to plan around than estate-and-gift taxes alone. Estate-and-gift taxes apply a wealth tax at one point in time: the point at which the wealth is transferred. As a result, it can become easier to set up structures, such as minority interests and trusts, to prepare to game valuation at that one point—as compared to having to plan around a wealth tax that is applied at regular intervals.

Notably, several countries currently administer recurring wealth taxes. Of the 34 developed and advanced-developing member nations of the OECD, 11 raised revenue from a recurring wealth tax as of 2013.82 The median amount raised among those countries with a wealth tax was about 0.4 percent of GDP, or equivalent to about $75 billion per year in the United States today. Countries with a wealth tax include France, which raises about 0.2 percent of GDP by imposing a wealth tax that affects those with total net wealth exceeding 1.3 million euros (though the French tax excludes a number of assets including business assets and antiques), and Switzerland, which raises about 1 percent of GDP with a tax that applies more broadly than the French version, though the rate varies by canton.

To be clear, though, regular wealth taxation in the United States would face administrative and potential legal challenges. The greatest administrative challenge would be regularly valuing assets that are not publicly traded. For the wealthiest Americans, such assets compose a significant share of their wealth. Estate tax data suggest that such assets comprise about one-half of total assets among the extremely wealthy, and that may understate the situation since these assets tend to be under-valued.83 In fact, battles over valuation in the estate-and-gift tax system can be lengthy. Of course, the estate-and-gift tax system does attempt to do such a valuation for all these assets, but it occurs only once per generation.

These administrative challenges are real, but many have been faced in other countries, where wealth taxes are administered—and so there are models from which to build. For instance, Switzerland recently sought to change the way it values shares in closely-held startups for purposes of its wealth taxes, weighing both simplicity of administration and possible liquidity constraints of startup owners.84