Overview

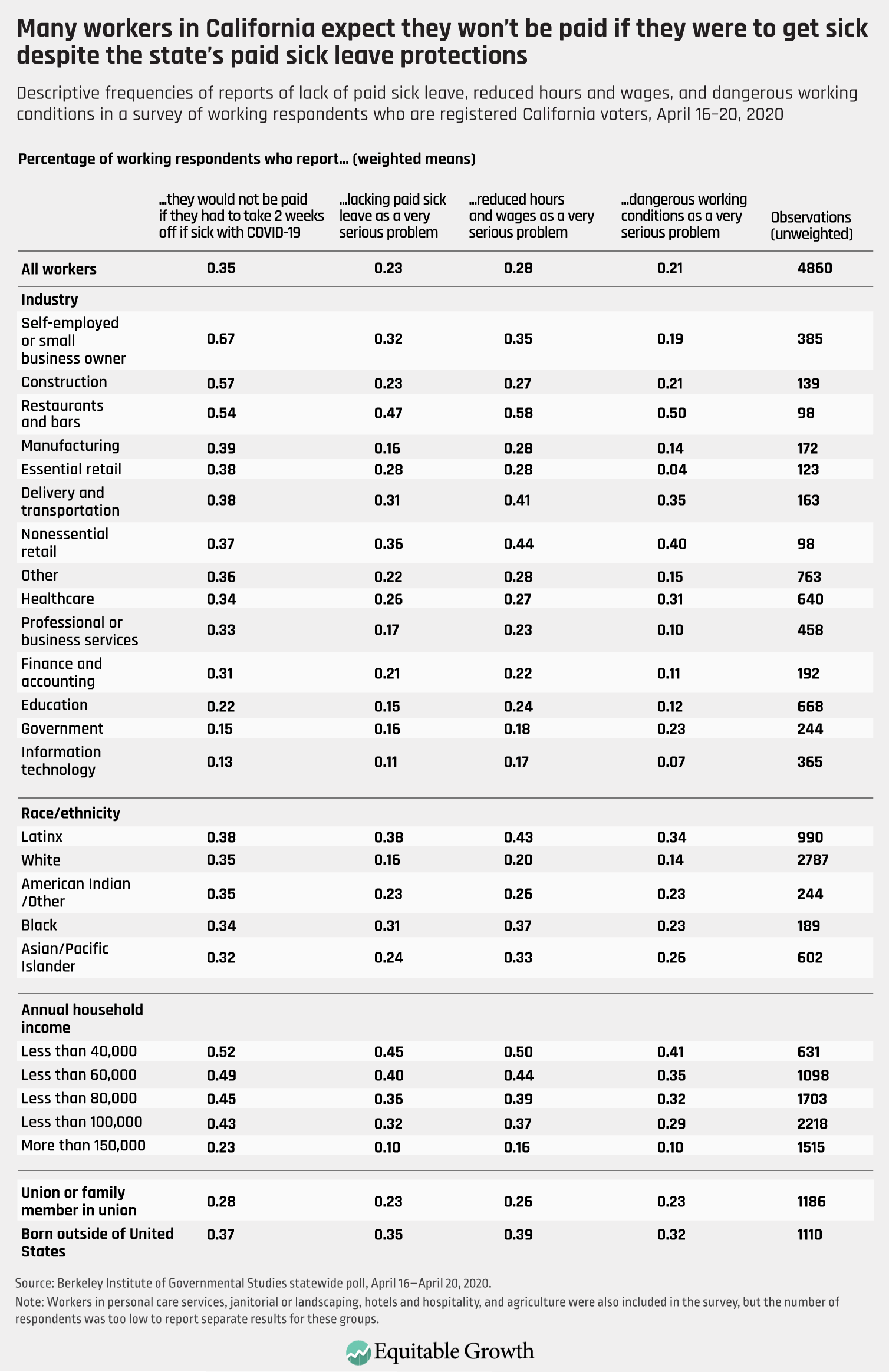

Workers in the United States are experiencing record unemployment at the same time that governments across the country are facing extraordinary budget deficits. Evidence from the Great Recession of 2007—2009 indicates high levels of unemployment weaken the labor market power of those low-wage workers who remain employed. As this report will demonstrate, minimum wage violations increased dramatically during the Great Recession and disproportionately impacted Latinx, Black, and female workers.

It is therefore critically important that federal, state, and local labor standards are vigorously and strategically enforced during times of economic stress. If minimum wage laws are not enforced during the current recession, then not only are the most vulnerable workers—those already struggling to make ends meet on poverty wages—at a higher risk of financial harm due to wage theft by their employers, but also the whole structure of wages in an industry or a city is weakened. Labor enforcement agencies at all levels of government must be both effective and strategic in their enforcement approaches while facing severe resource constraints that are likely to be exacerbated by recession-related shortfalls in government revenues and complicated by low-wage workers’ reluctance to make official complaints about wage theft lest they lose their jobs.

Download FileMaintaining effective U.S. labor standards enforcement through the coronavirus recession

This paper is divided into five sections. The first section demonstrates that as the unemployment rate rises, so too do labor standards violations, especially among low-wage workers who can least afford to have their wages stolen. The second section examines the problem with complaint-based enforcement in general, particularly in high-violation scenarios, drawing and building upon the results of our study of minimum wage violations in San Francisco. Relying solely on reactive, complaint-based enforcement means that violations against highly vulnerable workers who are unable or unwilling to complain will go unaddressed.

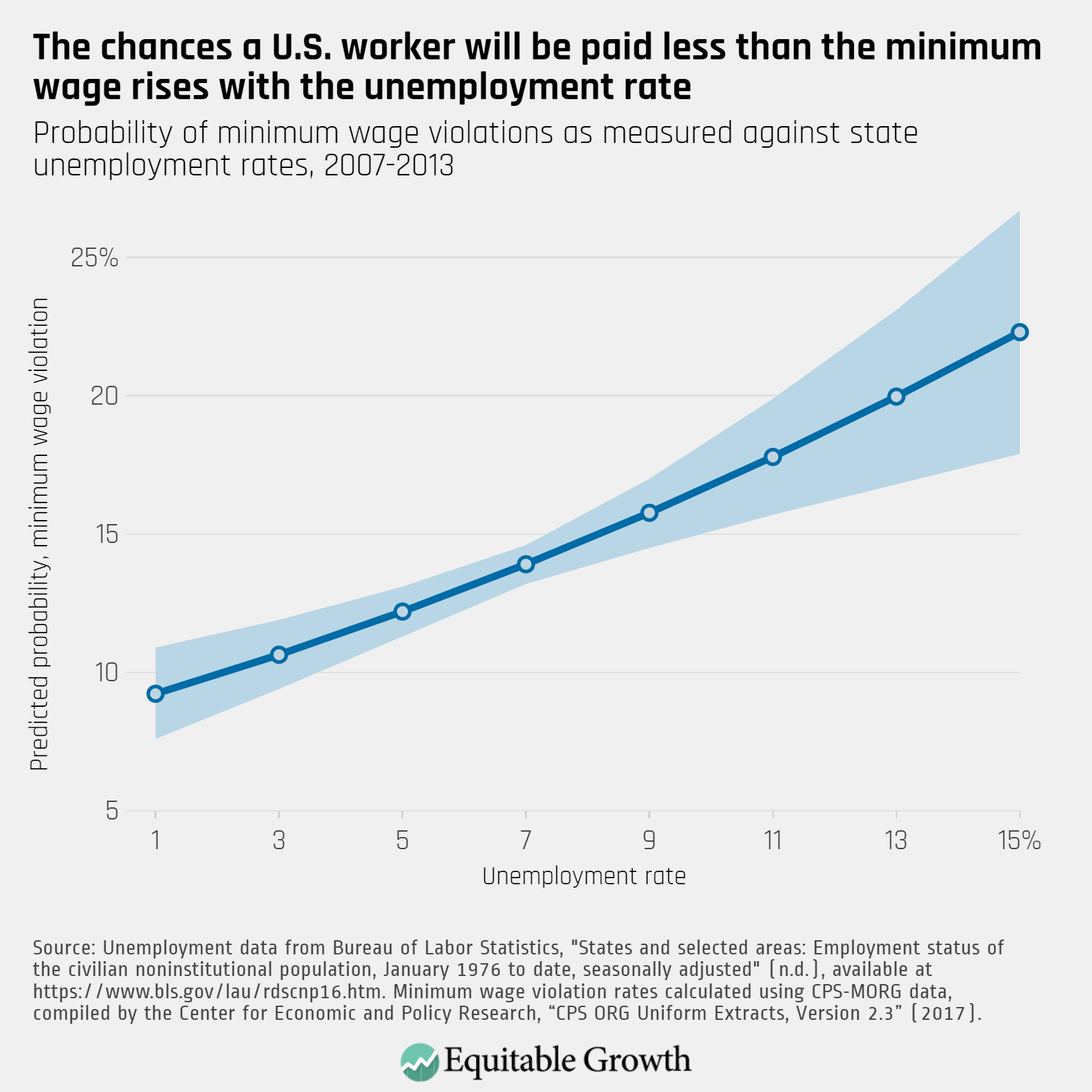

The third section draws on a survey of registered California voters in April 2020, amid the coronavirus pandemic, to describe workers’ understanding of their state-level and federal emergency paid sick leave protections by demographic characteristics and industry. The survey further illustrates a problem with complaint-based enforcement in the context of the pandemic—many of the most vulnerable workers are unaware of California’s paid leave policies and the federal emergency paid leave protections. We also use this dataset to describe workers’ perceived economic and physical vulnerabilities at work during the pandemic.

The fourth section describes the main elements of a strategic enforcement and co-enforcement approach, in which labor enforcement agencies target high-violation industries and maximize the use of enforcement powers that increase the cost of noncompliance in partnership with trusted community organizations. And the final section puts forward a series of federal policy recommendations that build worker power by incorporating strategic enforcement and co-enforcement into the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 and advance federal strategic enforcement efforts by providing for more robust enforcement powers. Specifically, we call for:

- Strengthening retaliation protections to more effectively hold violating employers liable

- Adopting policies to address “fissured” employment contracts that enable employers to avoid liability by subcontracting or relying on independent contractors

- Increasing damages, penalties, and fines to maximize deterrence

- Extending the statute of limitations for labor standards violations during administrative investigations to better remedy long-time violations and preserve civil actions

- Creating a rebuttable presumption that a violation occurred when an employer does not comply with recordkeeping requirements

- Providing additional enforcement avenues by establishing the right to full compensation

- Allowing employees to designate a representative for federal labor standards investigations to facilitate worker engagement in the enforcement process

- Incorporating a grant program to promote compliance with the Fair Labor Standards Act in low-wage sectors through co-enforcement

In these ways—detailed more thoroughly at the end of this report—federal labor enforcement standards can be reformed to meet the challenges of a changing U.S. labor market hit hard by the coronavirus recession.

Unemployment and labor standards violations: Lessons learned from the Great Recession

The coronavirus pandemic and the resulting abrupt disruption to the global economy is unprecedented in modern times. In February 2020, unemployment in the United States was at 3.5 percent, a 50-year low.1 By April 2020, unemployment rose to a staggering 14.7 percent, the largest increase in the history of the series.2 In just 2 months, job losses due to the pandemic—which disproportionately affected Latinx, Black, and female workers3—surpassed the total number of jobs lost from December 2007 to June 2009 during the period known as the Great Recession.4

Likewise, in April and May 2020, the number of unemployment benefit claims exceeded the total number of claims filed throughout the Great Recession.5 The Congressional Budget Office predicts a 5.6 percent decline in U.S. Gross Domestic Product in 2020, and that the annual unemployment rate will remain at approximately 9.3 percent in 2021.6 Further, while the duration of the current recession is still unclear, some economists are already predicting an L-shaped recession, in which U.S. unemployment will remain 5 percent above normal even 30 months after the pandemic first began.7

In addition to the extraordinary job losses in the private sector, the shuttering of the U.S. economy sharply reduced public revenues, which, combined with unanticipated expenditures related to the coronavirus pandemic and resulting recession, leaves governments at all levels with substantial deficits leading to mass layoffs of public-sector workers. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimates a federal deficit of $3.7 trillion for fiscal year 2020 ending September 30, 2020, and $2.1 trillion for FY 2021 (without accounting for any additional coronavirus relief funding, which Congress may yet pass).8

These revenue losses are being felt at the state level. California is anticipating a $54.3 billion budget deficit.9 New York state’s budget for FY 2021 now includes reduced estimates for FY 2021 general fund receipts by $13.3 billion.10 In response, New York plans to cut state spending by $7.3 billion in FY 2021, the largest annual percent decline since the Great Depression.11 Additionally, without further federal intervention, the state plans to cut aid to localities by $8.2 billion, reductions the state says “have no precedent in modern times.”12 For its part, California’s FY 2020–2021 budget includes $11.1 billion in reductions and deferrals unless the state receives $14 billion in federal funding by October 15.13

After experiencing what the state’s governor described as “the largest loss of income in our history,” Wyoming is anticipating $1 billion in revenue shortfalls in the current 2-year budget cycle.14 Accordingly, Wyoming announced a 10 percent cut to its general fund budget, which will require layoffs, furloughs, reduced major maintenance spending, and the consolidation of human resources personnel. These cuts, though, will not fully offset the state’s deficit, so the governor has further instructed Wyoming agencies to prepare to cut budgets by an additional 10 percent.15 Similarly, Ohio is facing the largest decline in GDP on record and was forced to reduce its FY 2020 budget by $775 million.16 In addition to budget cuts, the governor directed agencies to freeze hiring, new contracts, pay increases, and promotions.17 Cities are also predicting major cuts. New York City, for example, expects a $7.4 billion loss in tax revenue and, in response, has reduced its FY 2021 budget by $3.4 billion.18

While the circumstances surrounding the Great Recession are markedly different, data from that period provide insight into what we can anticipate amid the current coronavirus recession. Specifically, we can examine the relationship between the steep rise in unemployment during the Great Recession and the rate of minimum wage violations—wage theft by employers—during the same period. Between late 2007 and early 2010, the unemployment rate doubled to 10 percent from 5 percent before gradually declining in the slow recovery thereafter. Using data from the Current Population Survey—widely considered the best publicly available hourly wage data—we estimate minimum wage violations among low-wage workers (those in the bottom quintile of their state’s income distribution) by comparing individuals’ reported hourly wages to their applicable state or substate minimum wage (or, in the case of states without a minimum wage, the federal minimum wage).

Minimum wage violations are dichotomous measures of whether an individual was illegally paid less than their applicable statutory minimum wage. Statewide violation rates and unemployment rates can then be calculated and compared.19

Our research finds that the average statewide minimum wage violation rate rose steeply alongside the rising unemployment rate, peaked in early 2010, and fell slowly thereafter over the next 3 years, tracking the slow decline in unemployment. Although the average amount of money these workers lost due to wage theft hardly varied at all—each quarter, violations cost workers a remarkably steady 20 percent of what they were owed, or $1.46 per hour on average—the share of low-wage workers suffering minimum wage violations rose (and fell) significantly along with unemployment. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

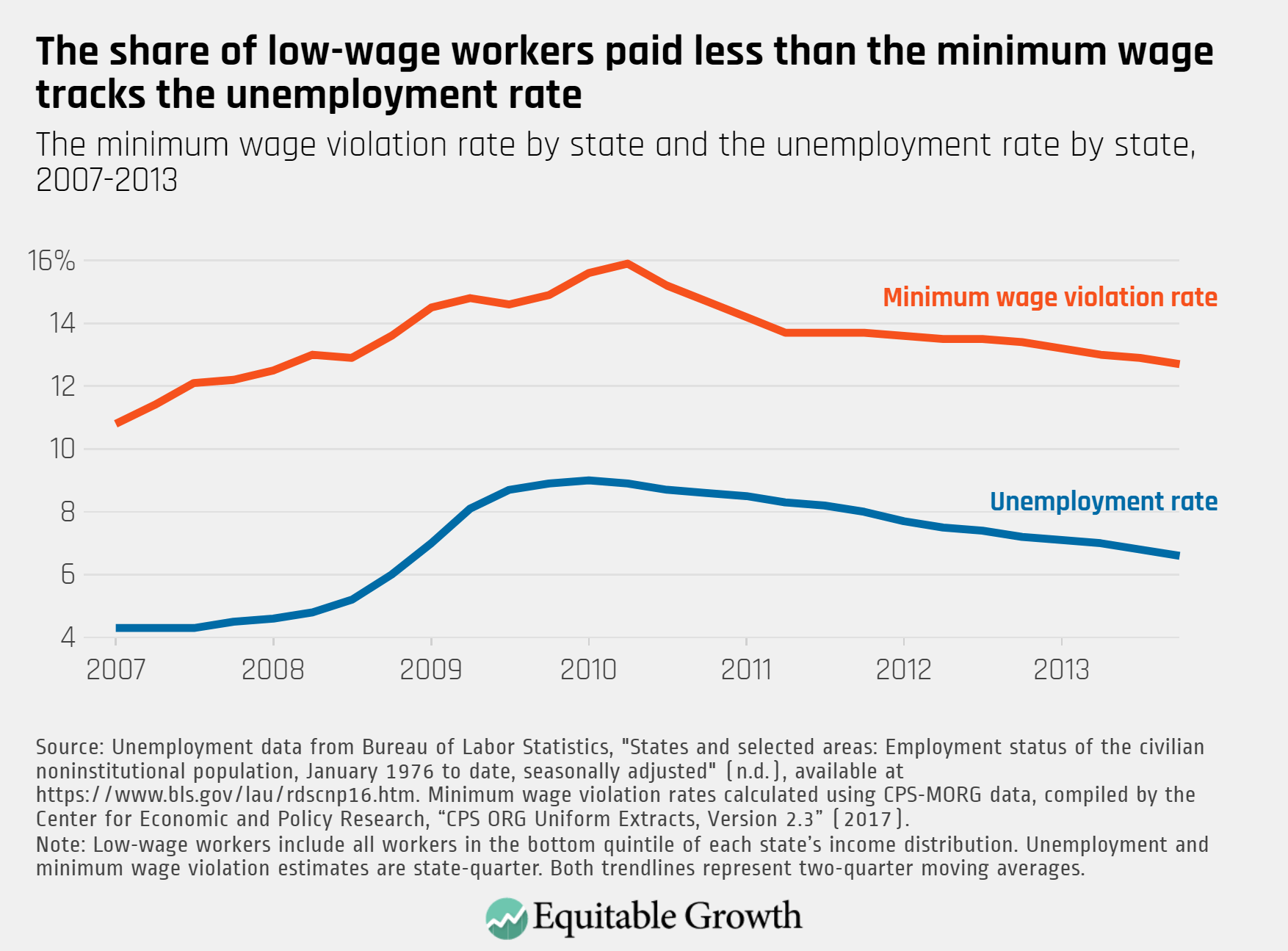

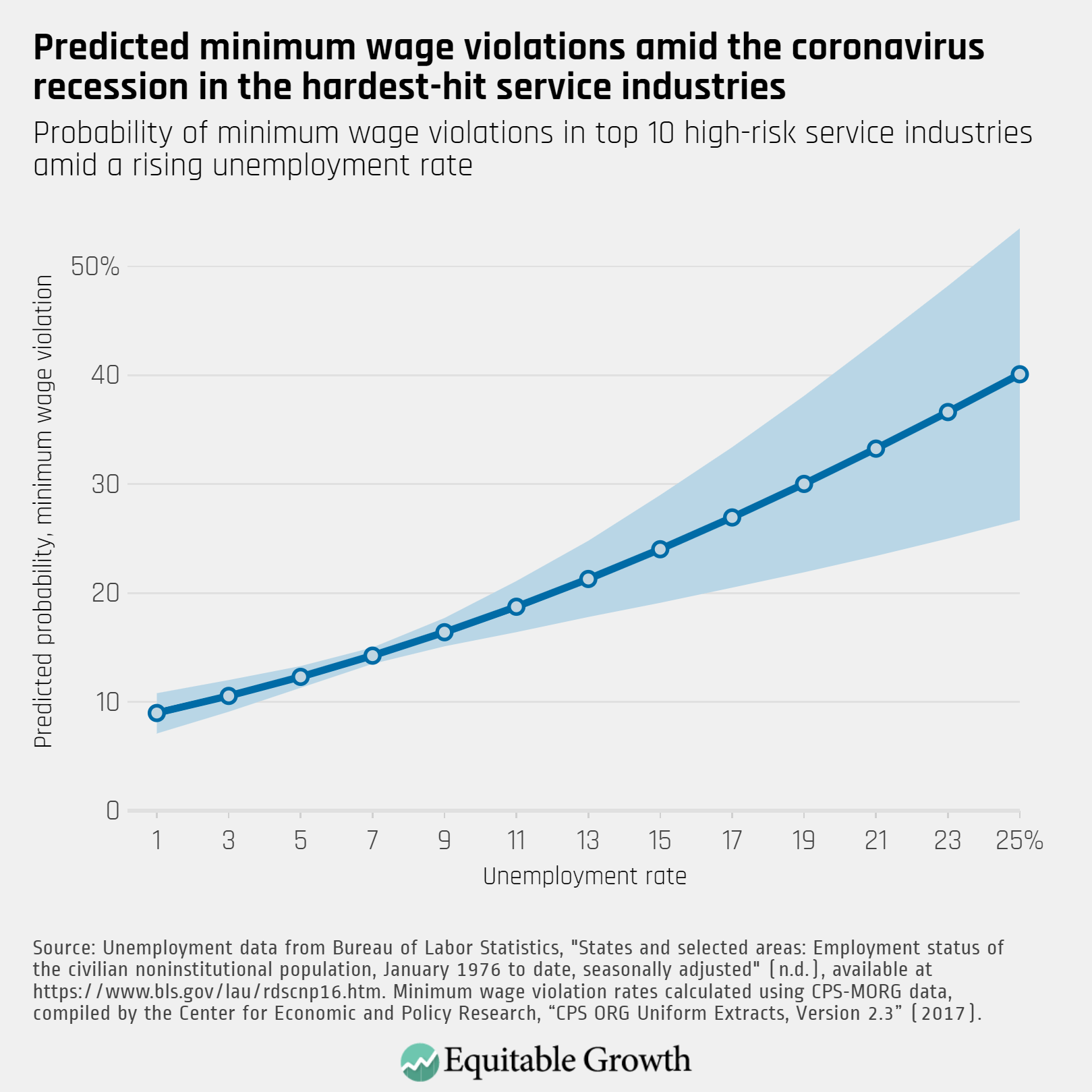

To examine the relationship in more fine-grained detail, we estimate the predicted probability that any given low-wage worker in the United States would suffer a minimum wage violation between 2007 and 2013. We find that the probability ranged from about 10 percent to about 22 percent, with each percentage point increase in his or her state’s unemployment rate predicting, on average, almost a full percentage point increase in the probability he or she would experience a violation. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Data from the Great Recession also can inform policymakers’ understanding of how low-wage workers in the industries hardest-hit by the coronavirus and COVID-19 might fare if unemployment continues to rise well beyond the levels of the Great Recession. Due to the unusual nature of a pandemic-triggered recession, the following industries are considered most at risk of job losses:

- Food services and drinking places

- Retail trade

- Personal and laundry services

- Arts, entertainment, and recreation

- Accommodation

- Private households

- Transportation and warehousing

- Membership associations and organizations

- Administrative and support services

- Social assistance20

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell recently suggested that the United States could hit an unemployment rate of 25 percent this year due to steep job losses in these industry categories, which make up about a third of the private-sector workforce, depending on the state.

Using the same categories as above, we can consider the effect of a 25 percent unemployment rate on low-wage workers in those industries.21 To be sure, many factors affect the elasticity of demand for labor, effective wage rates, and compliance with minimum wage laws, and so we do not attempt to offer here a fully specified forecasting model. But if the same basic relationships hold, then the minimum wage violation rate could reach 40 percent for vulnerable low-wage workers (plus or minus 13 percentage points). Given that most workers in these industries do not work in low-wage, front-line jobs—and are not therefore candidates for minimum wage violations—we think these estimates, though only suggestive, are sobering.22(See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

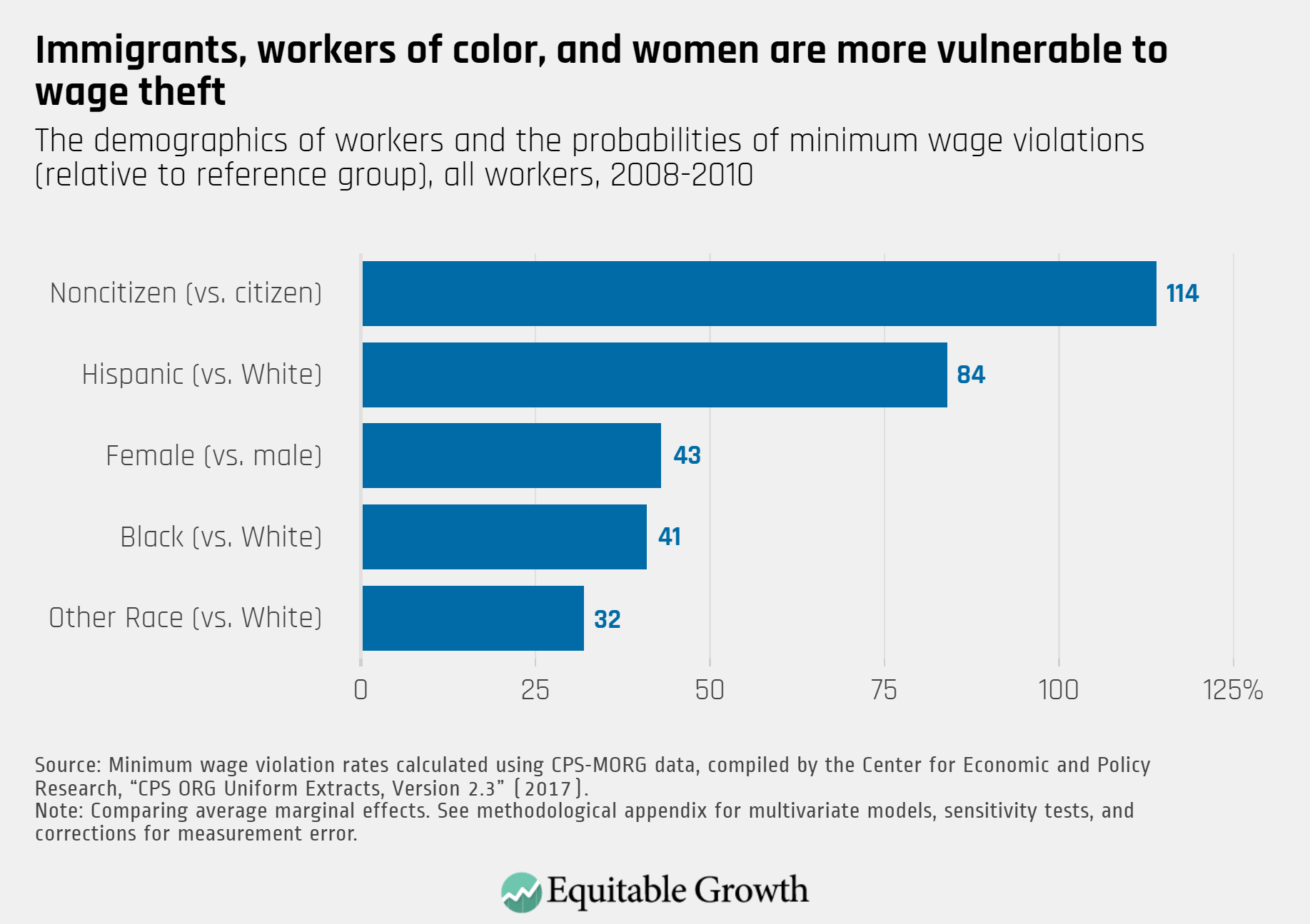

It is also worth noting that the negative consequences of the Great Recession were shouldered by some groups of workers more than others. To assess the relative likelihood that workers in key demographic groups would experience minimum wage violations (relative to reference group), we examine all workers in the period 2008-2010. We find that the probability of experiencing wage theft was two times greater for non-citizens relative to U.S. citizens; respondents coded “Hispanic” were 84 percent more likely than those coded “White”; women and respondents coded “Black” were almost 50 percent more likely than men and White respondents, respectively; and respondents coded “Other” were over 30 percent more likely than Whites. In addition, workers who belonged to a union were more than three times less likely to experience a minimum wage violation than workers who did not belong to a union. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

Workers’ vulnerability to wage theft depends, in large part, on their personal and demographic characteristics, and how they intersect. When the interaction of gender, race, and citizenship are taken into account, the effects of discrimination are compounded. During the Great Recession, Hispanic women who were not U.S. citizens, for example, were four times more likely to experience a minimum wage violation than White male citizens. Noncitizen Black women were 3.7 times more likely to experience wage theft than White male citizens. Both groups of women immigrant workers were about twice as likely to be underpaid than White women who were U.S. citizens.

Overall, noncitizen women of color (coded Black, Hispanic, or Other) were almost 50 percent more likely than women of color who were citizens to experience this pernicious form of wage theft. Irrespective of citizenship, Latinx women were 88 percent more likely and Black women were 38 percent more likely to suffer a minimum wage violation than White women.

Violations for not paying workers the minimum wage are bound to rise along with unemployment in 2020 as well, perhaps even more dramatically given the strong relationship we observed during the Great Recession. And funding for labor standards enforcement is almost certain to be cut due to the sharp descent into the coronavirus recession.

Troublingly, even in times of economic prosperity, there is little funding for labor standards enforcement. In a survey by Janice Fine, Greg Lyon, and Jenn Round at Rutgers University, conducted in 45 states and cities that have enacted labor standards laws between 2012–2016, 27 percent of the states received no additional funding at all for enforcement, and another 13 percent received $50,000 or less. At the city level, more than 50 percent have no funding whatsoever to carry out the new policies, and another 22 percent have $50,000 or less.23

The lack of funding at the state and local levels means that even in some jurisdictions that have passed state and local minimum wage laws, the U.S. Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division is the sole enforcement agency working to ensure compliance. The division, though, has its own resources crunch. As of May 1, 2020, for example, it employed 779 investigators to protect more than 143 million workers, which is significantly fewer than the 1,000 investigators employed in 1948, when the division was responsible for safeguarding the rights of only 22.6 million workers.24 Because of the tremendous budgetary deficits that state and local governments now face, we expect that at the same time that low-wage workers will experience increased violations, enforcement budgets across the country will be further reduced.

Out of concern for businesses suffering amid the coronavirus recession, some elected officials and agency personnel at the Department of Labor are arguing for a reduction in regulations or suspension of labor standards enforcement.25 It is vitally important to support business revival, but it must not be done at the cost of labor standards. Government could and should play a much more active role in providing small businesses with coaching, loans, and support for back office, accounting (payroll and taxation), and HR functions, but suspending enforcement would be harmful to the most vulnerable workers. This is especially the case for those who have been on the front lines in terms of risk during the pandemic and would be enormously destructive to wage floors and labor market standards.

Fundamentally, the argument that there should not be labor standards enforcement during a recession (or at any other time) amounts to saying that it is reasonable for an employer to take money from their workforce because they are unable to make their business produce a profit. Those companies that remain in business by not paying their workers are essentially forcing those workers to subsidize the business. And even if workers are eventually made whole, it is after an involuntary, interest-free loan from their employees who have no financial capacity to provide one.26

Moreover, if minimum wage laws are not enforced during a recession, the whole structure of wages in an industry or city is weakened. Allowing unfair competition by allowing wage theft amounts to the provision of informal concessions to weaker firms in an industry, which weakens the stronger firms that are in compliance. In this scenario, wage standards across labor markets are likely to decline, particularly in the low-wage sectors where so many essential workers are employed.

Consider the restaurant industry, which is well-known to have high rates of wage theft violations.27 If demand for restaurants’ food and drinks falls off, as is the case today, the problem must be addressed either by expanding demand or reducing supply, but not by reviving the industry by reducing minimum wage enforcement. If labor standards enforcement agencies ignore the violations of very marginal restaurants, then they undermine the compliant ones. In particular, they undermine those firms that may be just barely managing to stay in business yet not resorting to wage violations in order to do so.28

Lastly, research by labor economists demonstrates that firms weigh the costs and benefits of minimum wage compliance and are more likely to violate the law if there is a low probability of being investigated or face minimal fines even if they are caught.29 Relaxing minimum wage enforcement is certain to exacerbate this problem.

The challenge: Complaint-based enforcement overlooks violations against vulnerable workers

Labor enforcement agencies across the United States predominately use a reactive, complaint-based approach to labor standards enforcement, in which workers who experience a violation are expected to report it to the appropriate public agency in order for the violation to be investigated. Complaint-based enforcement became the default mode of enforcement in the early years of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 and largely remained so until the Obama administration.30

State and local enforcement agencies are also largely complaint-based. In the survey previously cited by Rutgers’ Fine, Lyon, and Round, 70 percent of cities surveyed indicated their enforcement is complaint-driven while 54 percent of states interviewed said the same.31 In the survey, most states were overwhelmingly complaint-based, except for child-labor cases, some of which were initiated without a formal complaint.

Despite the prevalence of complaint-based enforcement, the model itself is inadequate. First, complaint-based enforcement has failed to keep up with the growth of subcontracting and attenuated labor and product supply chains—new industrial structures and employment relationships that continue to evolve.32 Low-wage industries in particular are experiencing an explosion of what David Weil, the former head of the federal Wage and Hour Division of the U.S. Department of Labor, calls the “fissuring” of the employment relationship.33

Fissuring occurs when companies shift the direct employment of workers to other business entities through increased reliance on strategies such as subcontracting, use of temporary employees, and independent contracting arrangements.34 Often, firms are embedded in subcontracting networks, in which one large firm or a few firms are setting the terms of exchange but are not the employers of record for purposes of labor standards enforcement.

Second, complaint-based enforcement tends to embrace an individualized regulatory approach that conceives of each individual case—or worker complaint—as an isolated and idiosyncratic incident. This means that even a high number of individual cases or complaints are unlikely to lead to structural reforms across an industry. Agencies handle each worker complaint as a separate transaction that yields no other regulatory actions beyond opening and closing the particular case at hand, and so the case itself is severed from the broader structural context from which it emerged.35

Third, research on minimum wage enforcement suggests that workers in industries with the worst conditions are much less likely to complain about wage theft.36 Comparing complaint rates to estimates of underlying minimum wage violations in various state and local jurisdictions across the United States, we find an insufficient overlap to justify enforcement based solely on complaints.

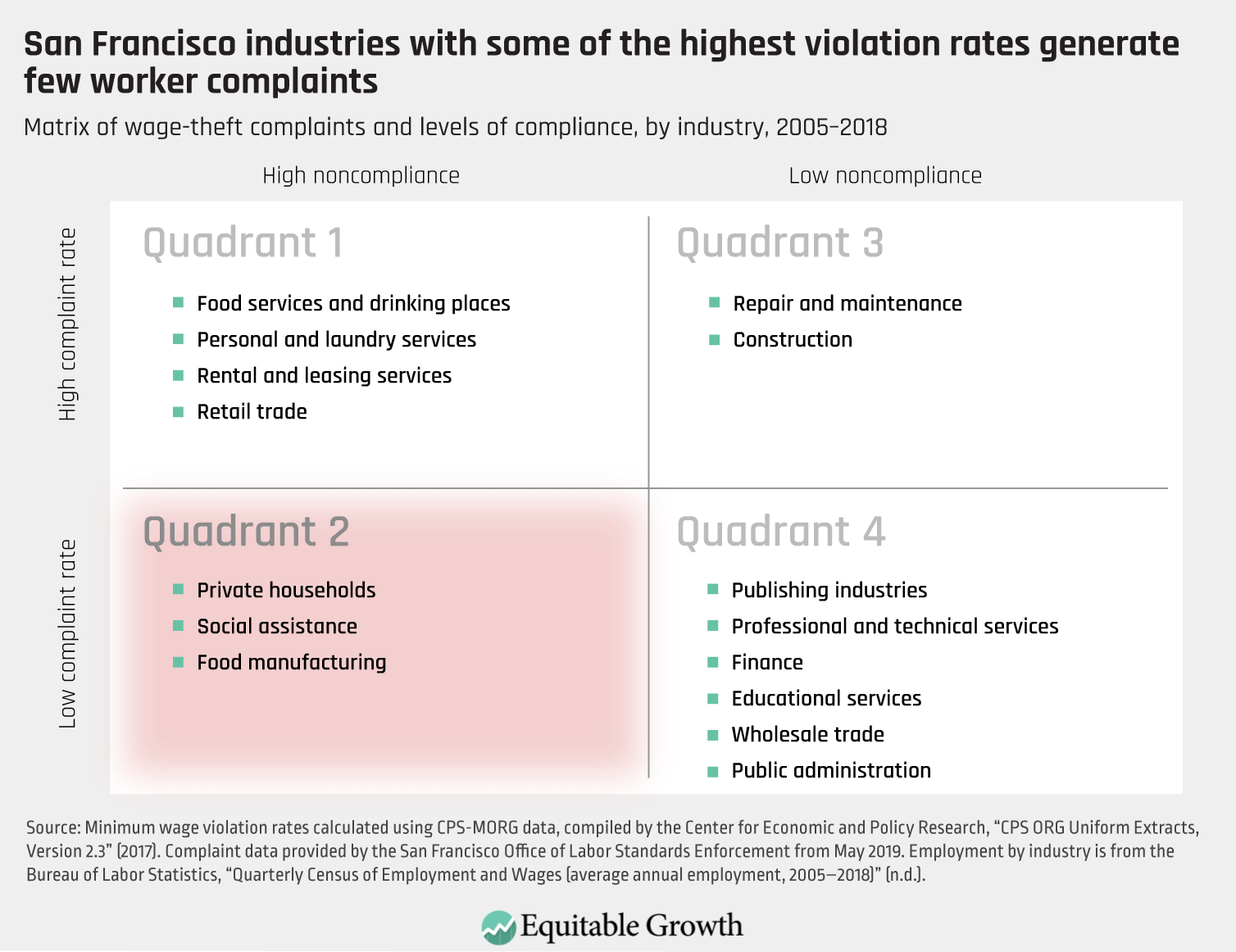

Even in some of the wealthiest and most progressive cities, there are stunning gaps between the industries with the highest rate of complaints and those with the highest violation rates. Our study of San Francisco, for example, demonstrates that in many industries, the number of minimum wage complaints reported to the San Francisco Office of Labor Standards Enforcement were disproportionate to estimated violation rates. We compared the actual number of complaints submitted to the agency to estimates of minimum wage violations by industry in 2005–2018 (again using Current Population Survey data). We find that violations in the private households, social assistance, and food manufacturing industry sectors were among the highest of any industry, but workers in these three industries made few complaints to the city’s labor standards enforcement agency.37 (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

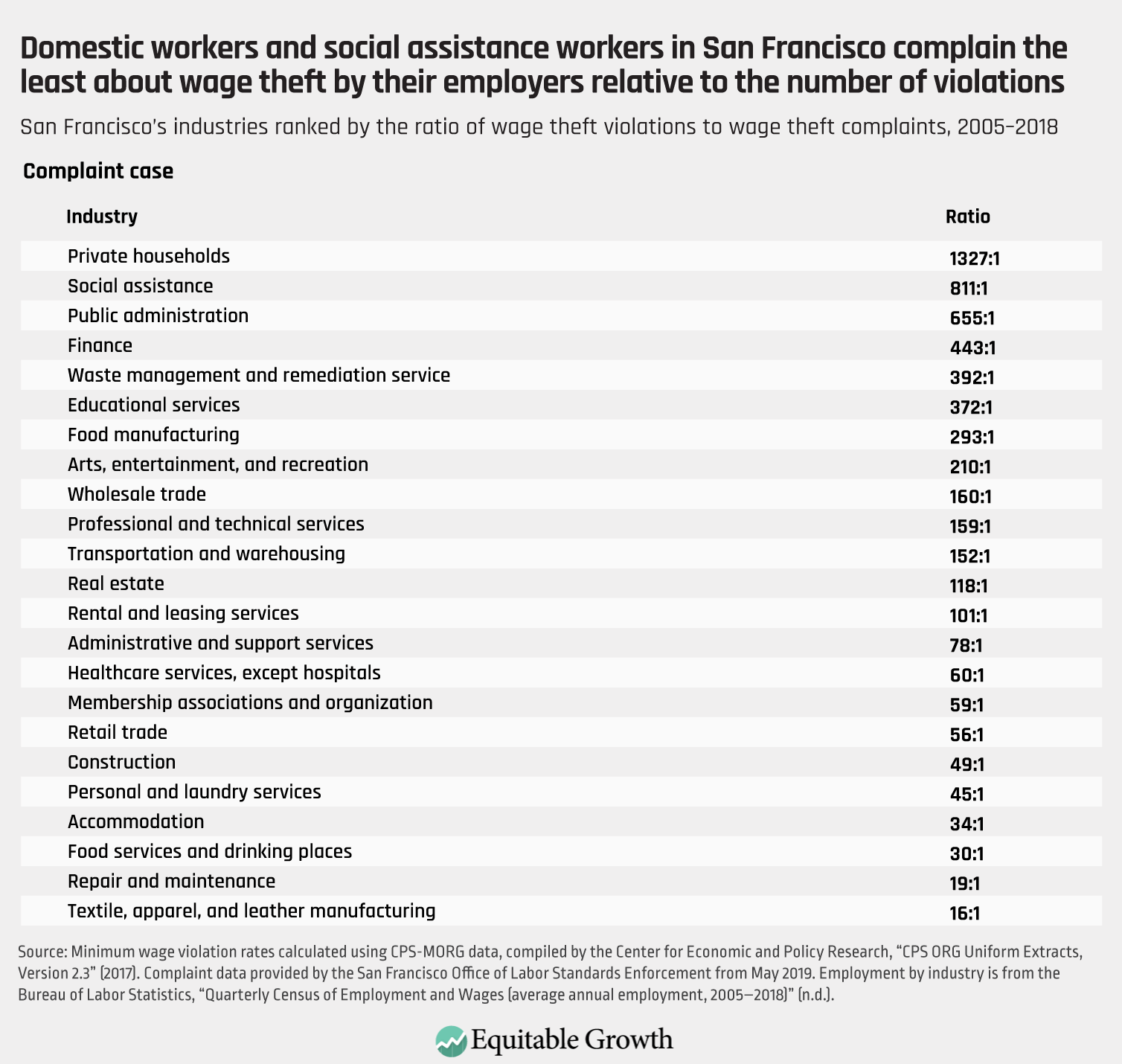

Another way to think about the extent of the discrepancy between individually driven complaints and minimum wage violations is to calculate a ratio for each industry.38 In San Francisco, more than 1,300 violations are estimated to occur for every one worker complaint in the private households industry. In social assistance, more than 800 violations occur for every one complaint.

In contrast, industries that are more compliant in their wage standards yet nevertheless receive many complaints (as detailed in Figure 5, quadrant 3 above) have much lower ratios, among them: 19:1 in the repair and maintenance industry and 50:1 in the construction sector. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

Such results demolish the premise of the complaint-based enforcement model—that workers whose rights are violated will speak up. To the contrary, we find that some of the most regularly exploited workers are among the least likely to complain, as detailed in quadrant 2 in Figure 5 above. In the complaint-based enforcement model, quiet industries are presumed to be compliant industries, not industries where workers are suffering silently.

The consequences of this faulty assumption are serious. Where enforcement is most needed, few investigations are triggered. Meanwhile, labor standards enforcement agencies inefficiently devote resources to pursuing complaints in far more compliant industries (as seen in quadrant 3 in Figure 5). These inequalities are only likely to be exacerbated in the context of a recession and particularly amid the current pandemic-induced recession.39

The discrepancy between individual complaints and business violations is caused by asymmetries of power between low-wage workers and the firms for which they work. Workers with the least power and few alternative employment options face barriers that keep them from stepping forward to complain much of the time.40 In a recession, high unemployment increases workers’ desperation to maintain any job, thus tipping the power imbalance even further toward firms. Just as noncitizen workers and workers of color became more vulnerable during the Great Recession, we expect the likelihood these workers will file a complaint to decrease even more amid the current coronavirus recession.

Indeed, we expect the coronavirus recession to push more industries with ratios of low compliance and few complaints (quadrant 2 in Figure 5) to continue in San Francisco and across the country. The April 2020 unemployment report showed that the biggest job losses across the United States, at -7,653, were in leisure and hospitality, an industry that includes the food services and drinking places subsector, followed by professional and business services (-2,165), retail trade (-2,106.9), and health care and social assistance (-2,086.9). Additionally, “other services,” an industry that includes personal and laundry services and private households, lost a considerable number of jobs (-1,267).41

Notably, workers in three of the four industries in San Francisco that fell into quadrant 1 in Figure 5 above—those with high noncompliance and many complaints—have lost a considerable number of jobs. The concern, then, is that high unemployment will render these workers in food services and drinking places, personal and laundry services, and retail trade industries more vulnerable to exploitation but less likely to complain.

In other words, those workers most impacted by the coronavirus recession could soon find themselves in the most problematic category of high violations but relatively few complaints (quadrant 2 in Figure 5). And they are largely overlooked by regulators adhering to complaint-based enforcement.

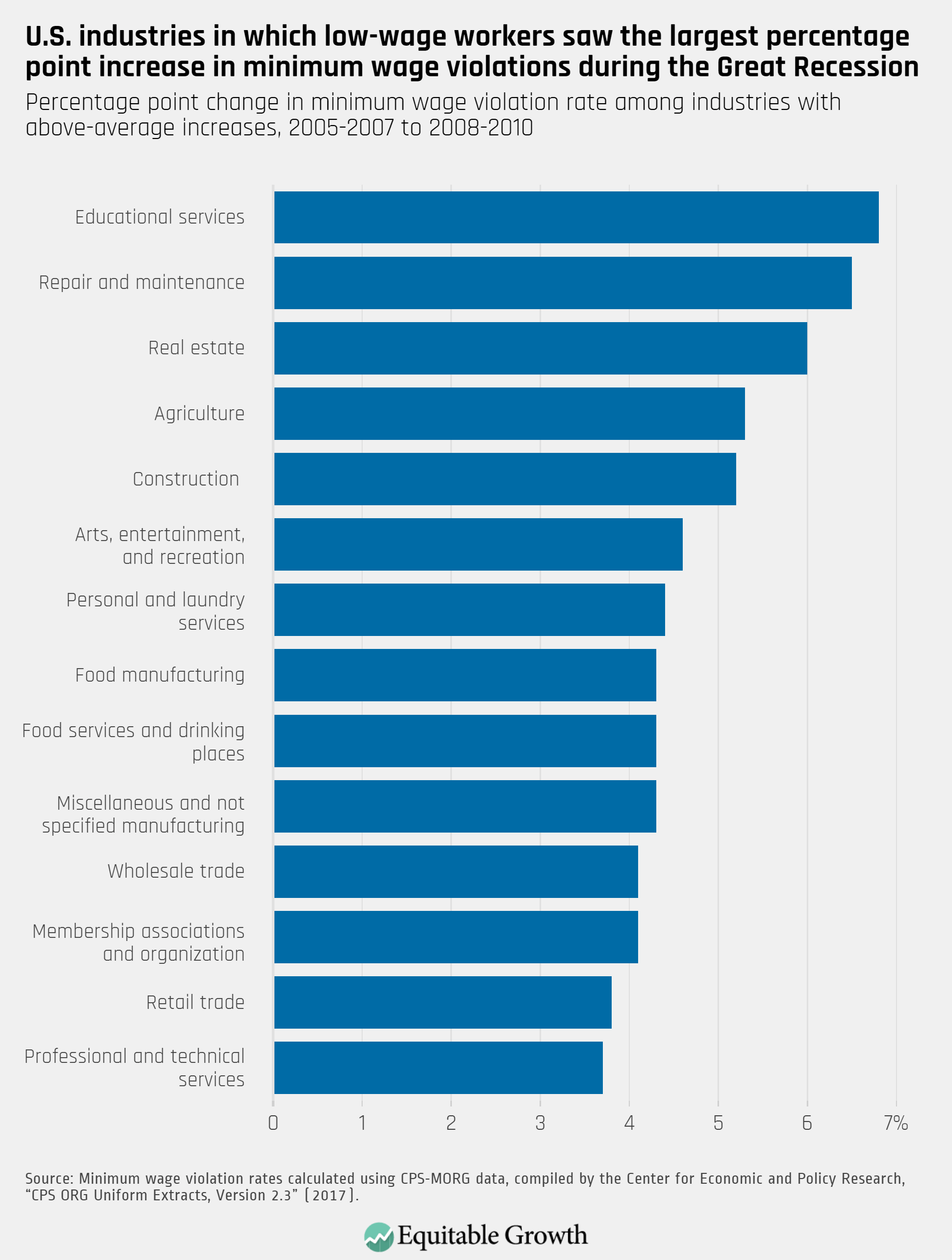

In the years just prior to the Great Recession, low-wage workers in educational services, for example, had a 13.5 percent probability of suffering a minimum wage violation. During the ensuing recession, their probability of experiencing wage theft rose to 20.4 percent. The educational services industry was not the highest-violation industry prior to the Great Recession—private households was, at 26 percent—but its rate of change was steeper than any other industry amid that recession, at 6.8 percent. Indeed, its increase was nearly two standard deviations above the mean.

In fact, many industries that are not ordinarily high-risk industries for minimum wage violations—including repair and maintenance, professional and technical services, retail trade, construction, and wholesale trade, all of which fall in the low noncompliance quadrants in Figure 5—became much more susceptible to minimum wage violations during the Great Recession. (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6

Protecting workers in difficult times: Strategic enforcement and co-enforcement

Given the likelihood of the persistence of the pandemic as a threat to worker health in turn sustaining the current recession, what is the most effective framework to enforce labor standards laws when workers are unaware of or do not trust existing protections, worker vulnerability and violations increase, and enforcement resources are further diminished? There are two primary, interrelated frameworks that answer this question: strategic enforcement and co-enforcement.

Strategic enforcement

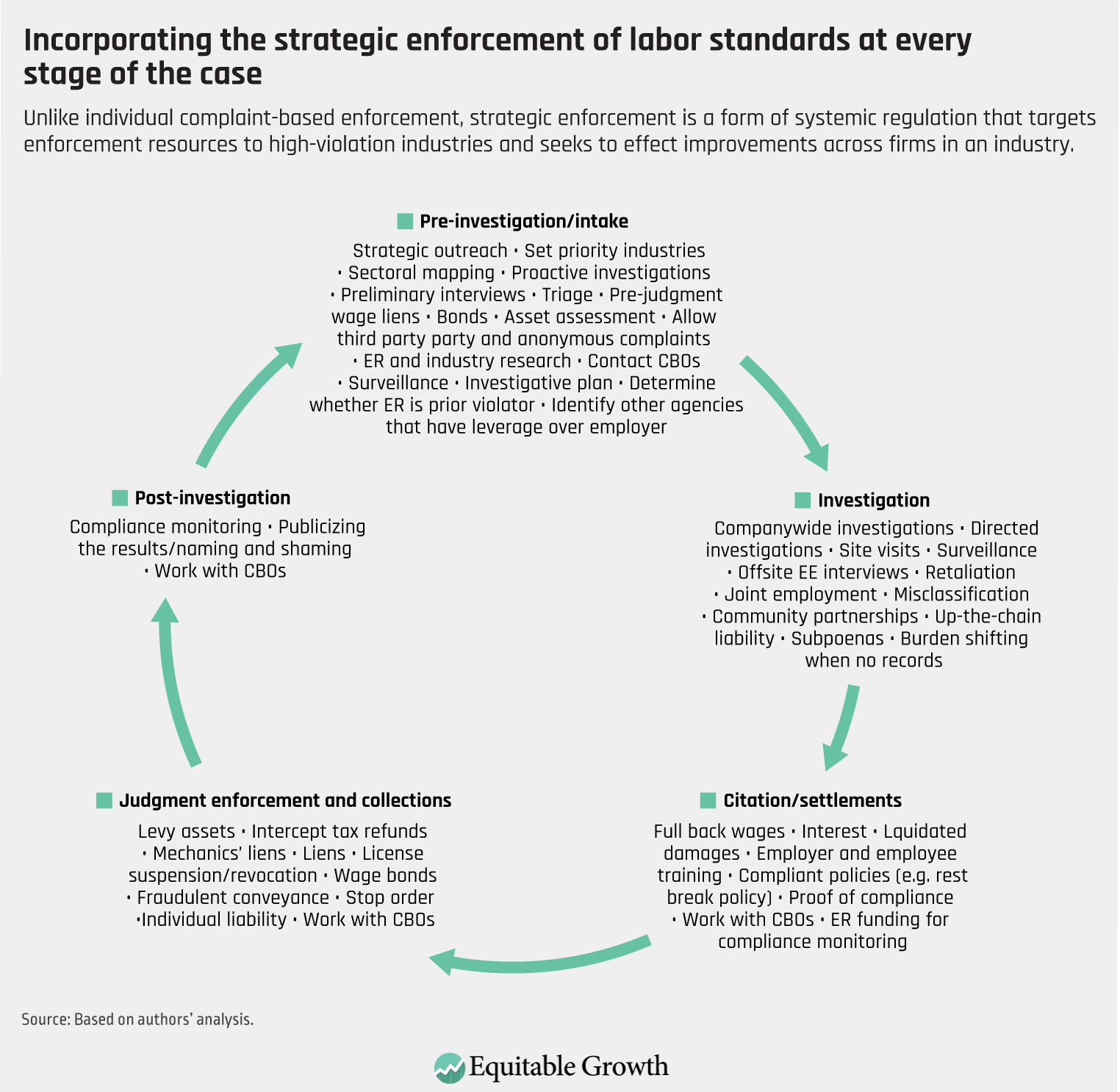

Strategic enforcement is a form of systemic regulation that conceives of each violation as a potential signal of a broader pattern of labor market violations. Unlike complaint-based enforcement, in which each case is typically processed as an isolated or idiosyncratic incident, a strategic enforcement model analyzes complaints for underlying causes and targets enforcement resources to high-violation industries.

As articulated by Weil, the former head of the U.S. Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division and now the dean of and a professor at the Heller School for Social Policy and Management at Brandeis University, the overarching goal of strategic enforcement is “to use the limited enforcement resources available to a regulatory agency to protect workers as prescribed by laws by changing employer behavior in a sustainable way.”45 At the federal level, the main components of strategic enforcement include a proactive, rather than reactive, approach to investigations, targeting industries high in violations but low in complaints, maximizing the extent of legal penalties imposed on violators, informational campaigns to businesses and workers, strategic communications and signaling to employers, robust compliance agreements with violators, and using data to measure effectiveness.46

Of course, federal, state, and local enforcement agencies operate in vastly different political climates and with a wide variety of statutory powers and bureaucratic limitations. Accordingly, strategic enforcement cannot be cast in “one size fits all” or “all or nothing” terms. Figure 7 below elaborates on the full complement of tools and techniques agencies can use at each stage of the process to achieve broad, long-term compliance. Agencies can adopt and incorporate some of these strategic practices and work toward adopting others by taking on administrative and statutory limitations over time.47 (See Figure 7.)

Figure 7

Strategic enforcement addresses gaps created by traditional complaint-based enforcement in several ways. First, the use of proactive investigations in targeted industries means enforcement resources are more likely to identify and reach vulnerable workers who are unlikely to complain. Likewise, industry research to identify industry structure, influential employers, and widespread, noncompliant industry practices helps agencies target employers that are likely to get the attention of others in the industry.

Under a strategic enforcement framework, proactive investigations are used in tandem with triage, a system for sorting complaints into different treatment categories to help agencies efficiently manage their resources so that high-violation industries with high and low complaint rates are prioritized.48 To be effective, this approach must be informed by data so that enforcement agencies have a firm basis for making decisions about where to dedicate resources.

Additionally, strategic enforcement includes maximizing the use of statutory tools that are designed to address common enforcement impediments. Fear of retaliation, for example, keeps workers from making complaints and cooperating during investigations.49 Savvy bad-faith employers who know that worker cooperation is critical to robust enforcement may use retaliation as a means to hinder an agency’s wage and hour investigations.

Similarly, low-road employers may flout recordkeeping requirements to avoid documenting noncompliance or otherwise falsify or destroy records when they learn of an investigation. Where the facts in an individual case indicate such wrongdoing, creative lawmakers have included “rebuttable presumptions” in labor standards laws to shift the burden onto employers to prove they were in compliance with the law. Strategic enforcement legal tools such as rebuttable presumptions help to disincentivize bad-faith actions while allowing enforcement agencies to more effectively enforce substantive labor standards rights against employers who engage in them anyway.

Moreover, strategic enforcement involves assessing high damages and penalties in addition to back wages owed. These measures deter future violations by changing the cost/benefit calculation some employers make when they decide that violating the law is worth the risk of being caught.50 A study conducted by one of the co-authors of this report, Northwestern University political scientists Daniel J. Galvin, finds that higher penalties and stronger enforcement capacities lead to lower rates of noncompliance with minimum wage laws, all else being equal. In particular, difference-in-difference models reveal that states that implemented “treble damages” for wage violations between 2005 and 2014 experienced statistically significant drops in the incidence of minimum wage noncompliance.51

Sustained compliance also requires holding those with the most power in the contracting relationship liable for downstream violations. This approach helps to address the fissuring of employment relationships and holds liable the entity with the most reputational risk—a tactic that is more likely to get the attention of the other powerful upstream companies in an industry. For that to happen, agencies need a press strategy that alerts other employers to the consequences of noncompliance. Indeed, the press is crucial for maximizing the ripple effects of agencies’ limited resources.52

Similarly, robust collections efforts and tools are necessary to ensure judgments are meaningful and workers, in fact, receive money they are owed.53 Innovative settlement terms that address the root of the violation and promote ongoing compliance are also key components of strategic enforcement.

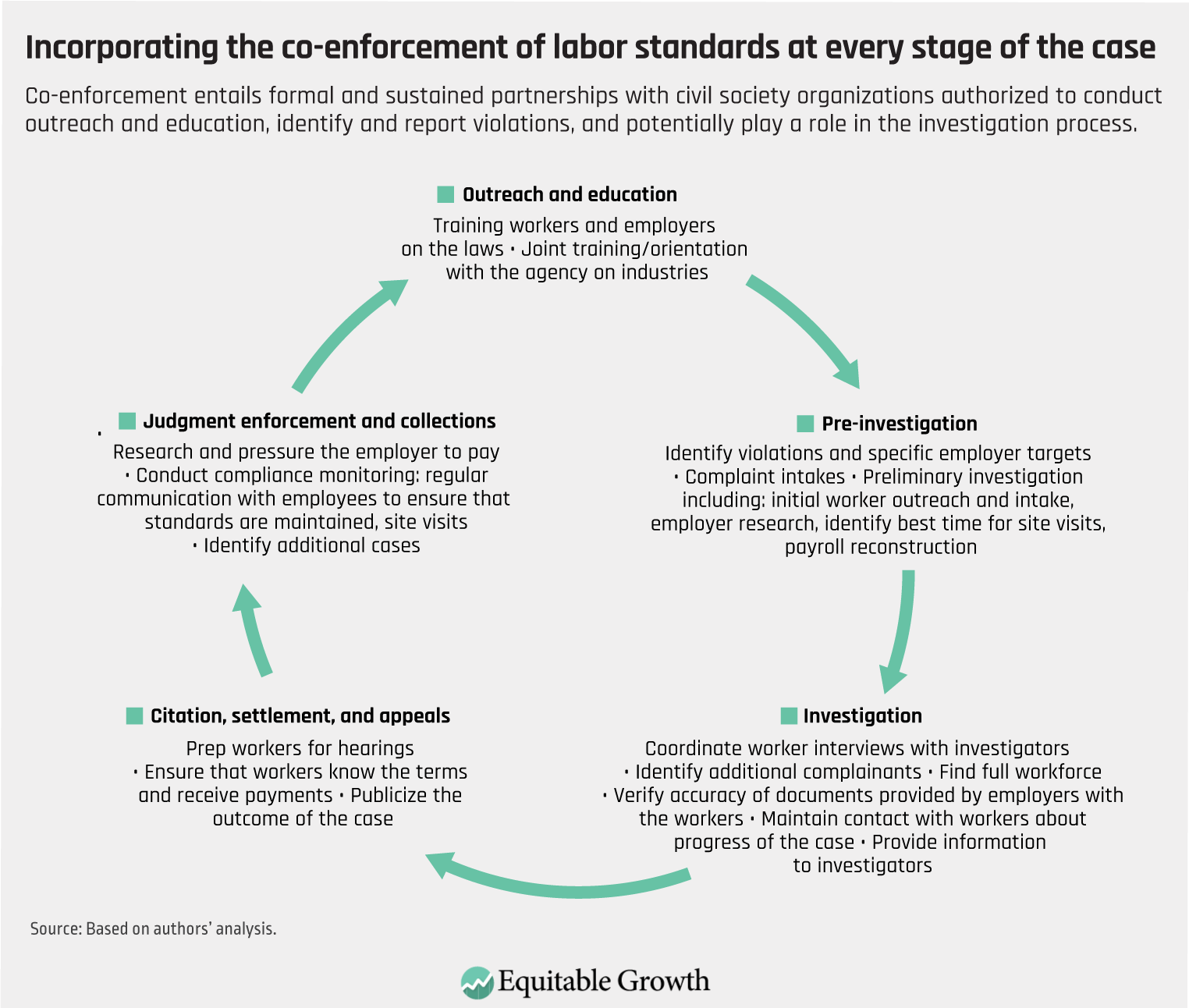

Co-enforcement

Strategic enforcement is a logical response to the coronavirus recession, but it will not succeed unless it is accompanied by a significant enhancement of worker voice.54 Simply put, problems will remain hidden unless workers speak up, yet vulnerable workers will not speak up in isolation. Likewise, as strategic enforcement includes moving to a more proactive investigative approach, it renders co-enforcement—formal and sustained partnerships with civil society organizations embedded in low-wage workers’ communities and high-violation sectors—essential to addressing the enforcement challenges created by the 21st century U.S. labor market.55

To illustrate this, we must consider why the vast majority of agencies continue to utilize the complaint-based enforcement model. One reason is that complaints often provide a foundation from which to build a strong case. In reacting to a complaint, before an investigation even begins, the agency has a cooperating witness and an array of information that may include the nature of the violations, how the employer may attempt to hide violations, names of management and ownership personnel, and other facts relevant to the case.

Worker participation and evidence is particularly important in establishing violations and back wages owed in more difficult investigations in which employers have no records or have falsified timesheets and payroll records to appear compliant. Without a connection to the workforce on which the agency can build an investigation, proactive investigations can be daunting and the agency may be unable to establish violations are occurring.

Worker organizations have access to information on labor standards compliance that would be difficult, if not impossible, for state officials to gather on their own.56 It is often only when the organization that has relationships with vulnerable workers has vouched for a government agency that they are willing to come forward. By building on existing trust between workers and organizations, investigators can gain access to the knowledge and information workers possess about violations.57

Additionally, through their relationships and local credibility, community organizations can educate workers, encourage them to file complaints, and help to gather testimony and documentation. Drawing on workers’ networks, community organizations can also recruit workers from problematic firms and industries by providing a safe space and interpretation and facilitation services, as well as helping state inspectors meet with workers who may be too intimidated to go to a government office. They also exercise a kind of moral power and broaden public support for robust enforcement when they document and publicize egregious examples and patterns of abuse.58

State enforcement agencies face a wide range of political pressures not to engage in vigorous enforcement. Worker organizations can act as countervailing points of pressure and, when an investigation is undertaken by an agency, through their relationships with workers, they can continue to monitor the employer over time, after inspectors have moved on to new cases.59 (See Figure 8.)

Figure 8

Federal policy recommendations to strengthen strategic enforcement and co-enforcement of labor standards

Given what we know about recessions, the transition to strategic enforcement and co-enforcement is imperative at all levels of government. An increase in violations and worker vulnerability renders proactive investigations, including at the state and local level, even more essential. Likewise, reductions to the budgets of enforcement agencies mean each investment of resources must be as effective as possible. Increased worker vulnerability also renders the role of community partners more vital. While we have extensive policy recommendations for state and local governments available,60 in this paper, we focus specifically on policy changes needed at the federal level.

Under Weil’s leadership during the Obama administration, the U.S. Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division maximized the use of available statutory tools.61 This increased the agency’s effectiveness.62 Yet the Fair Labor Standards Act lacks a number of important strategic enforcement tools, which keeps federal efforts from being as effective as they could be. Further, the Wage and Hour Division has not incorporated co-enforcement into its enforcement model, which has limited its ability to engage vulnerable workers.63 Below, we offer policies that should be adopted at the federal level to further build on the success of the division’s past strategic enforcement program.

Strengthen retaliation protections to more effectively hold retaliators liable

Retaliation, though pervasive, is notoriously difficult to prove.64 While federal wage and hour law provides some protections against retaliation, additional measures are needed to protect workers and hold retaliatory employers liable. The following policy changes are needed to strengthen federal retaliation protections:

- Create a rebuttable presumption that an adverse action taken within 90 days of a protected activity is retaliatory65

- Require clear and convincing evidence to rebut the presumption66

- Incorporate the motivating factor causation standard—meaning an employee’s exercise of a protected activity was a motivating factor in an employer’s adverse action—as opposed to the more common, but harder to meet, “but for” standard67

- Comprehensively define protected activities to expand retaliation protections beyond engaging in the enforcement process68

- Increase retaliation remedies to better account for the collateral impact of retaliation69

Adopt policies to address fissured employment

As industrial structures and employment relationships continue to evolve, new enforcement tools are needed to address the growth of increasingly complex production systems.70 With respect to subcontracting, federal law should incorporate policies that hold up-the-chain entities strictly liable for downstream violations.71

Further, as entire sectors rely on misclassifying employees as independent contractors to maximize profits and avoid liability for legal protections that include minimum wage and overtime, the Fair Labor Standards Act should be amended to streamline misclassification determinations by:

- Adopting a presumption that a worker is an employee until the alleged employer demonstrates the worker is, in fact, an independent contractor72

- Replacing the economic realities test with the “ABC” test (A, the worker is free from control or direction; B, the service provided is outside the alleged employer’s usual course of business; and C, the worker is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, profession, or business) to determine employment status73

Increase damages, penalties, and fines to maximize deterrence

As noted above, substantial monetary penalties are a crucial factor in decreasing violation rates. The Fair Labor Standards Act should be amended to provide for greater damages to aggrieved persons, which could be made available by way of daily penalties or higher liquidated damages.74 Penalties and fines also should be increased.75 Damages, fines, and penalties should be available in every investigation regardless of whether the violation was in good faith or the employer was a repeat offender.76

Extend the statute of limitations and incorporate tolling to better remedy longtime violations and preserve civil actions

Statutes of limitations determine the amount of time after an alleged violation occurs that an enforcement action can be brought.77 To ensure employers who violate labor standards laws can be held liable for back wages owed for longtime noncompliance and that any delay caused by the federal government’s inaction or capacity limitations after a complaint is filed does not preclude a lawsuit to remedy findings of violations,78 federal wage and hour laws should be amended to provide for a 6-year statute of limitations that tolls (legal parlance for suspending the statute of limitations) from the date a complaint is filed with the Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division or when the division commences an investigation, whichever is earlier, until the investigation is concluded.79 The amendment should be clear that all affected employees shall have the right to recover full wages and other damages accrued during the 6 years prior to the commencing of such action.

Include a rebuttable presumption for violating recordkeeping requirements to more efficiently hold bad-faith employers accountable

To incentivize compliance with recordkeeping requirements and otherwise deter employers from falsifying or destroying records when they learn of a labor standards investigation, a rebuttable presumption that the employer violated the Fair Labor Standards Act if the employer failed to turn over or maintain records should be adopted.80

Incorporate the right to full compensation to create additional avenues for enforcing state and local minimum wage laws

Where state or local minimum wage laws require a minimum wage higher than that established by the Fair Labor Standards Act, the federal Wage and Hour Division should be empowered to implement the will of the people by enforcing the applicable state or local minimum wage, as well as other laws or promises that require the payment of wages.81 Such authority would have the added benefit of allowing for enhanced coordination across jurisdictions where state and local enforcement agencies are active to better leverage the resources of multiple agencies.

To accomplish this, federal policy should require the payment of all wages, defined as all monetary compensation earned by an employee by reason of employment at the employee’s rate/s of pay, or the applicable rate/s of pay required by law, whichever is greater.82

Allow employees to designate a representative for federal labor standards investigations to facilitate worker engagement in the enforcement process

The Fair Labor Standards Act should be amended so employees may designate a representative to represent their interests in enforcement-related matters, including but not limited to:

- Filing complaints on behalf of employees

- Being present during employee interviews

- Participating in workplace inspections, conferences, and settlement negotiations83

Likewise, this policy should be clear that representatives may be third parties who are not employees, including unions, worker centers, community-based organizations, and nonprofit legal aid organizations. This policy also should require the federal Wage and Hour Division to routinely share information with the representatives as if they were complainants.84

Incorporate a grant program to promote compliance with the Fair Labor Standards Act in low-wage sectors through co-enforcement

The U.S. Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division should create a grant program as a first step in establishing co-enforcement partnerships with organizations that have deep connections to the workforce in specific communities and sectoral organizations with deep expertise in industries.85 From there, the division staff can develop the strong relationships and enforcement strategies that enable them to reach vulnerable workers, carry out the most impactful investigations, build the strongest possible cases that result in fines and penalties high enough to deter violations, and improve compliance with the Fair Labor Standards Act across localities, regions, and high-violation industries.86

Conclusion

We are facing a precarious time in our nation’s history. Over the past several decades, growing inequality, pay stagnation, decline in union participation, and deregulation have resulted in a labor market in which the balance of power has shifted substantially away from workers and toward employers. The coronavirus pandemic threatens to exacerbate this power imbalance and undo the progress made in cities, counties, and states that have raised the minimum wage and passed other innovative worker protection laws.

In order to maintain hard-fought state and local gains and consider passing additional federal worker protections, policymakers must prioritize legislation that empowers agencies with five key enforcement tools. Labor standards enforcement agencies need to be able to engage in enforcement strategies as sophisticated as the industries and companies they are meant to monitor. These agencies must be able to proactively target those sectors where vulnerable workers are experiencing high rates of violations. They need to implement robust retaliation protections, partnering with organizations these workers trust. And they need to be empowered to impose damages and penalties high enough to compel compliance.

About the authors

Janice Fine is the director of research and strategy at the Center for Innovation in Worker Organization at Rutgers University’s School of Management and Labor Relations. She holds a Ph.D. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in political science and is a professor of labor studies and employment relations at the Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations.

Daniel Galvin is a fellow at the Center for Innovation in Worker Organization, working on strategic enforcement initiatives. He holds a Ph.D. from Yale University and is an associate professor of political science and faculty fellow at the Institute for Policy Research at Northwestern University.

Jenn Round is a senior fellow with the labor standards enforcement program at the Center for Innovation in Worker Organization. She holds a J.D. from George Washington University Law School and a LL.M. from the University of Washington School of Law.

Hana Shepherd is an assistant professor of sociology at Rutgers University-New Brunswick. She holds a Ph.D. from Princeton University in sociology.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Michael Piore, David Weil, Greg Lyon, and Katherine Glassmyer for their feedback and contributions, as well as to Cristina Mora and Eric Schickler at the University of California, Berkeley, who designed and conducted the IGS poll. Warm thanks also go to the Washington Center for Equitable Growth for supporting our research.

Bibliography

Contributions of State and Worker Organizations in Argentina and the United States.” Regulation and Governance 11 (2): 129–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12122.

Partnerships Between Government and Civil Society Are Showing the Way Forward.” The University of Chicago Legal Forum 2017 (7): 143–76. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol2017/iss1/7.

Labour Standards Non-Compliance in the United States.” Osgoode Hall Law Journal 50 (4): 813–44. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj/vol50/iss4/3.

Enforcement in Immigration Reform.” Journal on Migration and Human Security 5 (2): 431–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/233150241700500211.

Enforcement of Labor Standards in the United States.” Journal of Industrial Relations 61 (2): 252–76. https://www.doi.org/10.1177/0022185618784100.

Threats to Workers.” Edited by Janice Fine, Pronita Gupta, and Jenn Round. Washington and New Brunswick: CLASP and the Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations. https://smlr.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/2019_addressingandpreventingretaliation.pdf.

Percent.” Politico. May 17. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/05/17/powell-unemployment-depression-25-percent-264500.

Employment Standards.” The Economic and Labour Relations Review 22 (3): 117–40. https://www.doi.org/10.1177/103530461102200308.

http://nber.org/cycles/US_Business_Cycle_Expansions_and_Contractions_20120423.pdf.

https://obm.ohio.gov/wps/wcm/connect/gov/36f3d5eb-f0bf-4042-8ec7-b2ce4bd0d4b9/State+of+Ohio+Monthly+Financial+Report+for+July+2020.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CONVERT_TO=url&CACHEID=ROOTWORKSPACE.Z18_M1HGGIK0N0JO00QO9DDDDM3000-36f3d5eb-f0bf-4042-8ec7-b2ce4bd0d4b9-nftYsj0.

End Notes

1. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment Situation News Release,” Press release, March 6, 2020, available at https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/empsit_03062020.htm.

2. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “The Employment Situation – May 2020,” Press release, August 7, 2020, available at https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf.

3. Specifically, while employment between February 2020 and April 2020 declined by 16 percent overall, it decreased by 18 percent for female workers, 18 percent for Black workers, and 21 percent for Latinx workers. See Congressional Budget Office, Interim Economic Projections for 2020 and 2021 (2020): p. 4, available at https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2020-05/56351-CBO-interim-projections.pdf.

4. National Bureau of Economic Research, “U.S. Business Cycle Expansion and Contractions” (2012), available at http://nber.org/cycles/US_Business_Cycle_Expansions_and_Contractions_20120423.pdf.

5. Victoria Gregory, Guido Menzio, and David G. Wiczer, “Pandemic Recession: L or V Shaped?” Working Paper 27105 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020): p. 1, available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w27105.pdf.

6. Congressional Budget Office, Interim Economic Projections, p. 7.

7. Gregory, Menzio, Wiczer, “Pandemic Recession,” p. 13.

8. Phil Swagel, “CBO’s Current Projections of Output, Employment, and Interest Rates and a Preliminary Look at Federal Deficits for 2020 and 2021” (Washington: Congressional Budget Office, 2020), available at https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56335.

9. Office of the Director, Fiscal Update (California Department of Finance, 2020): p. 4, available at http://www.dof.ca.gov/Budget/Historical_Budget_Publications/2020-21/documents/DOF_FISCAL_UPDATE-MAY-7TH.pdf.

10. New York State, FY 2021 Enacted Budget Financial Plan (2020): p. 8, available at https://www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy21/enac/fy21-enacted-fp.pdf.

11. Ibid., p. 9.

12. Ibid., p. 16.

13. California, State Budget 2020-21 (2020): p. 2; available at http://www.ebudget.ca.gov/2020-21/pdf/Enacted/BudgetSummary/FullBudgetSummary.pdf.

14. Wyoming Office of the Governor, “Governor Instructs Agencies to Prepare Deeper Budget Reductions,” Press release, June 4, 2020, available at https://governor.wyo.gov/media/news-releases/2020-news-releases/governor-instructs-state-agencies-to-prepare-deeper-budget-reductions; Wyoming Office of the Governor, “Budget Cuts Approved by Governor Gordon Total More than $250 Million,” Press release, July 13, 2020), available at https://governor.wyo.gov/media/news-releases/2020-news-releases/budget-cuts-approved-by-governor-gordon-total-more-than-250-million.

15. Wyoming Office of the Governor, “Budget Cuts Approved by Governor.”

16. Ohio Office of Budget Management, Monthly Financial Report (2020), available at https://obm.ohio.gov/wps/wcm/connect/gov/36f3d5eb-f0bf-4042-8ec7-b2ce4bd0d4b9/State+of+Ohio+Monthly+Financial+Report+for+July+2020.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CONVERT_TO=url&CACHEID=ROOTWORKSPACE.Z18_M1HGGIK0N0JO00QO9DDDDM3000-36f3d5eb-f0bf-4042-8ec7-b2ce4bd0d4b9-nftYsj0.

17. Ohio Office of the Governor, “Covid-19 Update: State Budget Impact,” Press release, May 5, 2020, available at https://governor.ohio.gov/wps/portal/gov/governor/media/news-and-media/covid19-update-may-5-2020.

18. New York City Office of the Mayor, “Facing Unprecedented Crisis, Mayor de Blasio Unveils Budget Plan that Protects New Yorkers by Prioritizing Health, Safety, Shelter and Access to Food,” Press release, April 16, 2020, available at https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/259-20/facing-unprecedented-crisis-mayor-de-blasio-budget-plan-protects-new-yorkers-by.

19. Methodological details are available from the authors.

20. Sarah Thomas, Annette Bernhardt, and Nari Rhee, “Industries at Direct Risk of Job Loss from COVID-19 in California: A Profile of Front-line Job and Worker Characteristics” (Berkeley: UC Berkeley Labor Center, 2020), available at http://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/industries-at-direct-risk-of-job-loss-from-covid-19-in-california/; Brandon McKoy, Janice R. Fine, and Todd E. Vachon, “New Jersey’s Service Sector Industries Most Likely to be Harmed by COVID-19” (New Brunswick: New Jersey Policy Perspective and Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations, 2020), available at https://www.njpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/NJPP-Policy-Brief-Service-Sector-Industries-Most-Likely-to-be-Harmed-by-COVID-19-1.pdf.

21. Victoria Guida, “Fed’s Powell Warns Unemployment Could Reach Depression-Level 25 Percent,” Politico, May 17, 2020, available at https://www.politico.com/news/2020/05/17/powell-unemployment-depression-25-percent-264500.

22. Thomas, Bernhardt, and Rhee, “Industries at Direct Risk of Job Loss.”

23. Janice Fine, Greg Lyon, and Jenn Round, “The Individual or the System: Regulation and the State of Subnational Labor Standards Enforcement in the U.S.,” unpublished manuscript, last modified April 2020.

24. Daniel J. Galvin, “Deterring Wage Theft: Alt-Labor, State Politics, and the Policy Determinants of Minimum Wage Compliance,” Perspectives on Politics 14 (2) (2016): 341, available at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592716000050; Department of Labor, FY 2020 Congressional Budget Justification: Wage and Hour Division (n.d.), p. 10, available at https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/general/budget/2020/CBJ-2020-V2-09.pdf; Data re: 2020 investigators is from the Department of Labor, received June 17, 2020, in response to FOIA 892698.

25. Executive Order no. 13924, Code of Federal Regulations, title 3, section 1 (2020), available at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/05/22/2020-11301/regulatory-relief-to-support-economic-recovery, stating, “Agencies should address this economic emergency by rescinding, modifying, waiving, or providing exemptions from regulations and other requirements that may inhibit economic recovery…”

26. Personal communication from David Weil, June 4, 2020.

27. For example, the U.S. Department of Labor found that 84 percent of the more than 9,000 restaurants investigated were in violation of wage and hour laws. See Elise Gould and David Cooper, “Seven Facts about Tipped Workers and the Tipped Minimum Wage” (Washington: Economic Policy Institute, 2018), available at https://www.epi.org/blog/seven-facts-about-tipped-workers-and-the-tipped-minimum-wage/; Annette Bernhardt, Michael W. Spiller, and Nik Theodore. “Employers Gone Rogue: Explaining Industry Variation in Violations of Workplace Laws,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 66 (4) (2013): 808–32, available at https://doi.org/10.1177/001979391306600404.

28. Personal communication with Michael Piore, May 15, 2020.

29. Orley Ashenfelter and Robert S. Smith, “Compliance with the Minimum Wage Law,” The Journal of Political Economy 87 (2) (1979), available at https://doi.org/10.1086/260759; David Weil, “Public Enforcement/Private Monitoring: Evaluating a New Approach to Regulating the Minimum Wage,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 58 (2) (2005), available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/30038575.

30. Janice Fine, “New Approaches to Enforcing Labor Standards: How Co-Enforcement Partnerships Between Government and Civil Society Are Showing the Way Forward,” The University of Chicago Legal Forum 2017 (7) (2017): 145, available at https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol2017/iss1/7; David Weil, “Creating a Strategic Enforcement Approach to Address Wage Theft: One Academic’s Journey in Organizational Change,” Journal of Industrial Relations 60 (3): 441, available at https://www.doi.org/10.1177/0022185618765551.

31. Fine, Lyon, Round, “The Individual or the System.”

32. David Weil, “Improving Workplace Conditions Through Strategic Enforcement: A Report to the Wage and Hour Division” (Boston: U.S. Department of Labor, 2010), available at http://www.dol.gov/whd/resources/strategicEnforcement.pdf; Damian Grimshaw and others, “Introduction: Fragmenting Work Across Organizational Boundaries.” In Mick Marchington and others, eds., Fragmenting Work: Blurring Organizational Boundaries and Disordering Hierarchies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015); Michael Piori and Andrew Schrank, Root Cause Regulation: Protecting Work and Workers in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018).

33. Weil, “Improving Workplace Conditions.”

34. Ibid.

35. Piore and Schrank, “Root Cause Regulation.”

36. David Weil and Amanda Pyles, “Why Complain? Complaints, Compliance, and the Problem of Enforcement in the U.S. Workplace,” Comparative Labor Law and Policy Journal 27 (1) (2005): 59, available at https://hctar.seas.harvard.edu/files/hctar/files/hr08.pdf; Janice Fine and Jennifer Gordon, “Strengthening Labor Standards Enforcement through Partnerships with Workers’ Organizations,” Politics and Society 38 (4) (2010): 556, available at https://www.doi.org/10.1177/0032329210381240.

37. Daniel J. Galvin, Janice Fine, and Jenn Round, “A Roadmap for Strategic Enforcement: Complaints and Compliance with San Francisco’s Minimum Wage” (forthcoming), p. 4. This research replicates and builds upon Weil and Pyles’s groundbreaking study, Weil and Pyles, “Why Complain?”

38. Weil and Pyles, “Why Complain?”

39. Janice Fine, “Solving the Problem from Hell: Tripartism as a Strategy for Addressing Labour Standards Non-Compliance in the United States,” Osgoode Hall Law Journal 50 (4) (2013): 820–21, available at https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj/vol50/iss4/3; Janice Fine and Jenn Round, “Federal, State, and Local Models of Strategic Enforcement and Co-Enforcement across the U.S.” (forthcoming).

40. Shannon Gleeson, “From Rights to Claims: The Role of Civil Society in Making Rights Real for Vulnerable Workers,” Law and Society Review 43 (3) (2009), available at https://www.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5893.2009.00385.x; Fine, “Problem from Hell,” p. 815.

41. U.S. Department of Labor, “The Employment Situation – May 2020.”

42. The survey was administered by the Institute of Governmental Studies, or IGS, in conjunction with the California Institute of Health Equity and Action, or Cal-IHEA. Post-stratification weights were applied to align the sample to population characteristics of the state’s overall registered voter population. The estimated sampling error, due to the effects of sample stratification and the post-stratification weighting, associated with the results from the survey, is approximately +/ 3 percentage points at the 95 percent confidence level. All descriptive statistics are reported using the survey weights. These results are simple means by group; they do not account for the overlap between these different status characteristics.

43. National Conference of State Legislatures, “Paid Sick Leave” (2020), available at https://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/paid-sick-leave.aspx.

44. Minimum Wage: In-Home Supportive Services: Paid Sick Days, California Senate Bill SB-3, April 4, 2016, available at https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520160SB3.

45. Weil, “Creating a Strategic Enforcement Approach,” p. 437.

46. Ibid.; David Weil, “Enforcing Labour Standards in Fissured Workplaces: The US Experience,” The Economic and Labour Relations Review 22 (2) (2011); David Weil, The Fissured Workplace: Why Work Became So Bad for So Many and What Can Be Done to Improve It (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014).

47. Fine and Round, “Federal, State, and Local Models,” pp. 4–5.

48. For more information on triage, see Jenn Round, “Tool 1: Complaints, Intake, and Triage,” Janice Fine and Tanya L. Goldman, eds. (Washington and New Brunswick: CLASP and the Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations, 2018), available at https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/publications/2018/09/2018_complaintsintakeandtriage.pdf.

49. Tanya Goldman, “Tool 5: Addressing and Preventing Retaliation and Immigration-Based Threats to Workers,” Janice Fine, Pronita Gupta, and Jenn Round, eds. (Washington and New Brunswick: CLASP and the Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations, 2019), p. 2, available at https://smlr.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/2019_addressingandpreventingretaliation.pdf.

50. Weil, “Public Enforcement/Private Monitoring.”

51. Galvin, “Deterring Wage Theft.”

52. For example, one study found that OSHA press releases resulted in an 88 percent decrease in violations at other facilities in the same sector within a 5-kilometer radius and led to an especially large decrease in willful or repeat violations and those most likely to lead to a severe incident. See Matthew S. Johnson, “Regulation by Shaming: Deterrence Effects of Publicizing Violations of Workplace Safety and Health Laws,” American Economic Review (conditionally accepted, 2019), available at https://drive.google.com/file/d/1HcKpGXZuFWNNLa1YTl0A4Hte1BiJabT-/view?usp=sharing.

53. For comprehensive information regarding strategic enforcement tools, including collections, the Center for Innovation in Worker Organization and the Center for Law and Social Policy created the Labor Standards Enforcement Toolbox, available at https://smlr.rutgers.edu/content/labor-standards-enforcement-toolbox (last accessed August 27, 2020), which is a series of briefs highlighting effective enforcement policies and how agencies have employed them to more effectively enforce laws in their jurisdictions.

54. Fine, “Problem from Hell,” p. 815.

55. Janice Fine and Tim Bartley, “Raising the Floor: New Directions in Public and Private Enforcement of Labor Standards in the United States,” Journal of Industrial Relations 61 (2) (2018): 257, available at https://www.doi.org/10.1177/0022185618784100; Matthew Amengual and Janice Fine, “Co-Enforcing Labor Standards: The Unique Contributions of State and Worker Organizations in Argentina and the United States,” Regulation and Governance 11 (2) (2017), available at https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12122; Janice Fine and Gregory Lyon, “Segmentation and the Role of Labor Standards Enforcement in Immigration Reform,” Journal on Migration and Human Security 5 (2) (2017), available at https://doi.org/10.1177/233150241700500211; Fine and Gordon, “Strengthening Labor Standards Enforcement”; Fine, “New Approaches.”

56. Tess Hardy, “Enrolling Non-State Actors to Improve Compliance with Minimum Employment Standards,” The Economic and Labour Relations Review 22 (3) (2011), available at https://www.doi.org/10.1177/103530461102200308; Fine and Gordon, “Strengthening Labor Standards Enforcement”; Fine, “Problem from Hell”; Amengual and Fine, “Co-Enforcing Labor Standards.”

57. Janice Fine, “Enforcing Labor Standards in Partnership with Civil Society: Can Co-Enforcement Success Where the State Alone Has Failed?” Politics and Society 45 (3) (2017): 364, available at https://www.doi.org/10.1177/0032329217702603.

58. JJ Chun, Organizing at the Margins: The Symbolic Politics of Labor in South Korea and the United States (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009); Janice Fine, Worker Centers: Organizing Communities at the Edge of the Dream (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2006); James M. Jasper, The Art of Moral Protest: Culture, Biography, and Creativity in Social Movements (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008); Cesar F. Rosado Marzan, “Worker Centers and the Moral Economy: Disrupting through Brokerage, Prestige, and Moral Framing,” The University of Chicago Legal Forum 2017 (7) (2017), available at https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol2017/iss1/16.

59. Fine and Bartley, “Raising the Floor,” p. 257. The success of combining strategic enforcement with co-enforcement is not merely theoretical. In California, Julie Su’s appointment as labor commissioner in 2011 placed a longtime advocate from a community organization who had seen firsthand the inadequacies of the existing system into a top leadership position. Su revolutionized the enforcement model and internal culture of the agency such that the California Labor Commissioner’s Office, or LCO, marshalled its full powers, sought additional powers from the legislature over time (with the support of labor and community allies), systematically changed management and personnel practices, and brought community partners into the very center of its strategic enforcement efforts. These changes achieved powerful results. Through its partnerships, LCO has been able to focus its resources on cases of a greater magnitude, resulting in the agency finding more violations per investigation and more wages owed to workers in LCO’s history. Under Su, LCO increased the ratio of violations to investigations from 49 percent in 2010 to 150 percent in fiscal year 2017–2018, and wages assessed per inspection rose from $1,402 in 2010 to $28,296 in 2017–2018. As LCO noted, “better targeting leads (to) fewer law-abiding employers to be inspected, more unpaid wages to be found, and more citations to be issued per employer.” See Bureau of Field Enforcement, 2017-2018 Report on the Effectiveness of the Bureau Field Enforcement (CA Labor Commissioner’s Office, n.d.), p. 3 and pp. 8–9, available at https://www.dir.ca.gov/dlse/BOFE_LegReport2018.pdf.

60. Jenn Round, “Building Block 1: Essential Labor Standards Enforcement Powers,” Janice Fine, ed. (New Brunswick: Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations, 2019), available at https://smlr.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/19_1011_basic_enforcement_powers_draft_7_e_distrib.pdf.

61. Interestingly, though most states and cities continue to rely on complaint-based enforcement, a number of jurisdictions have passed labor standards laws that provide stronger strategic enforcement tools than are available under the FLSA.

62. For example, as proactive investigations increased from 24 percent of all investigations in 2008 to 50 percent in 2017, the likelihood proactive investigations would result in a finding of a violation also significantly increased. See Weil, “Creating a Strategic Enforcement Approach,” p. 441, p. 449.

63. See Fine and Round, “Federal, State, and Local Models,” pp. 11–12.

64. See Goldman, “Addressing and Preventing Retaliation,” p. 9; Laura Huizar, “Exposing Wage Theft Without Fear: States Must Protect Workers from Retaliation” (New York: National Employment Law Project, 2019), pp. 4–5, available at https://s27147.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/Retal-Report-6-26-19.pdf.

65. Such presumptions are relatively common in state and local labor standards laws. See, for example, AZ Rev. Stat. Ann. § 23-364 (2016); NJ Stats. Annot. § 34:11D-4(b) (2018); Minneapolis Code of Ord. § 40.590(c) (2019); Los Angeles Municipal Code § 188.04 (2016).

66. See, for example, Minneapolis Code of Ord. § 40.590(c); Seattle Municipal Code 14.19.055(d) (2014).

67. The motivating factor standard requires showing that the exercise of protected activity was a cause in the employer taking an adverse action, whereas the “but for” standard requires showing the protected activity was the cause. For examples of motivating factor standards see Minneapolis Code of Ord. § 40.590(b); Seattle Municipal Code 14.19.055(e).

68. Seattle’s law provides a nonexclusive list of examples of protected activity that, in addition to filing complaints and cooperating in the enforcement process, includes the right to inform others about their rights; the right to inform a union or similar organization about an alleged violation; and the right to refuse to participate or oppose an unlawful act. Unlike the FLSA, Seattle’s law also protects “any person” who has exercised, in good faith, a protected activity. This nuance precludes arguments as to whether the person against whom the adverse action was taken was an “employee” or independent contractor, an analysis that can significantly slow a retaliation investigation. Seattle Municipal Code § 14.19.055(b). See also Goldman, “Addressing and Preventing Retaliation,” p. 4.

69.

While the FLSA does include broad powers to remedy retaliation, state and local jurisdictions have passed policies with more generous damages payable to aggrieved parties, as well as fines for retaliation. For example, while damages are limited under the FLSA to liquidated damages equal to lost wages, Arizona’s law requires retaliating employers pay a daily penalty to each impacted person of not less than $150 for each day the violation continued or until legal judgment is final. Notably, the law provides only the floor for this daily penalty, which gives the agency leeway to increase damages depending on the circumstances and egregiousness of the retaliatory act. Likewise, in San Francisco, in addition to daily damages to aggrieved parties, retaliators are liable for a penalty of $1,000 per employee to further deter retaliation. See AZ Rev. Stat. Ann. § 23-364(G); San Francisco Municipal Code § 12R.16(b) (2006).

Flexibility in awarding damages to affected workers are necessary to adequately address the indirect costs of retaliation, which can be extensive. A low-wage worker who misses even one paycheck after a retaliatory termination, for instance, may be unable to pay their rent or other bills, which could result in eviction or late fees and/or a reduced credit score, thus increasing the harm of retaliation. For further discussion of the wide range of potential costs resulting from retaliation, see Huizar, “Exposing Wage Theft Without Fear,” pp. 13–15.

70.

Despite this, the Trump administration has enacted rules that render it more difficult for the U.S. Wage and Hour Division to hold responsible entities liable for FLSA violations. See 29 C.F.R. §§ 791.1-791.3 (2020), which significantly limits joint employer liability under the FLSA. In response to this rule, 17 states and the District of Columbia filed a lawsuit challenging the rule, which took effect in March 2020. In their complaint, in New York v. Scalia, No. 20-01689 (S.D.N.Y. 2020), the plaintiffs noted,

“Over the past few decades, businesses have increasingly outsourced or subcontracted many of their core responsibilities to intermediary entities, instead of hiring workers directly. Because these intermediary entities tend to be less stable, less well funded, and subject to less scrutiny, they are more likely to violate wage and hour laws. As a result, employees that find work through intermediaries, such as subcontractors and temporary or staffing agencies, earn significantly less than their counterparts directly hired into permanent positions.”

The plaintiffs continued,

“The Final Rule would upend this legal landscape by providing a de facto exemption from joint employment liability for businesses that outsource certain employment responsibilities to third parties …. (Accordingly, t)he Final Rule makes workers even more vulnerable to underpayment and wage theft … (and it) provides an incentive for businesses best placed to monitor FLSA compliance to offload their employment responsibilities to smaller, less-sophisticated companies with fewer resources to track hours, keep payroll records, and train managers. It is estimated the Final Rule will cost workers, many of whom work at minimum wage jobs and live paycheck to paycheck, more than $1 billion annually.”

71. For example, California passed a law holding “client-employers” liable where workers are provided to the client-employer by a labor contractor that fails to pay wages. CA Labor Code § 2810.3 (1937); see also CA Labor Code § 238.5 (1937); Cal. Labor Code § 218.7 (1937). Such laws obviate the need for agencies to establish the upstream entity is a joint employer, an often complicated legal question that can significantly delay an otherwise straightforward wage and hour investigation. Indeed, California’s client-employer law was the basis for a co-enforcement action against the Cheesecake Factory and its janitorial subcontractors that resulted in $4.57 million citation. See Department of Industrial Relations, “News Release: Labor Commissioner’s Office Cites Cheesecake Factory, Janitorial Contractors More than $4.5 Million for Wage Theft Violations,” Press release, June 11, 2018, available at https://www.dir.ca.gov/DIRNews/2018/2018-40.pdf.

72. Such a presumption is included in Seattle’s minimum wage ordinance. See Seattle Municipal Code § 14.19.005. For further discussion regarding the importance of a legal presumption of employee status, see Tanya Goldman and David Weil, “Who’s Responsible Here? Establishing Legal Responsibility in the Fissured Workplace.” Working Paper No. 114 (Institute for New Economic Thinking, 2020), pp. 50–52, available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3551446.

73. The economic realities test is notoriously “a complex and manipulable multifactor test which invites employers to structure their relationships with employees in whatever manner best evades liability.” Jennifer Middleton, “Contingent Workers in a Changing Economy: Endure, Adapt, or Organize?” N.Y.U. Review of Law & Social Change 22 (1997): 557, available at https://socialchangenyu.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Jennifer-Middleton_RLSC_22.3.pdf. Accordingly, multiple states, including Massachusetts, New Jersey, Vermont, and California, have adopted the ABC test to “provide greater clarity and consistency, and less opportunity for manipulation than a test or standard that invariably requires the consideration and weighing of a significant number of disparate factors on a case-by-case basis.” See Dynamex Operations West, Inc. v. Superior Court of Los Angeles, 416 P.3d 1 (Cal. 2018), available at https://law.justia.com/cases/california/supreme-court/2018/s222732.html. Typically, the ABC test has three factors, all of which the alleged employer must demonstrate in order for the worker to be an independent contractor: 1) The worker is free, under contract and in fact, from control or direction; 2) The service provided is outside the alleged employer’s usual course of business; and 3) The worker is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, profession, or business.

74. Currently, the FLSA provides that the U.S. Wage and Hour Division may recover liquidated damages equal to wages owed. Fair Labor Standards Act, § 216(c). But see Portal to Portal Pay Act, U.S. Code 29 § 260 (1947), allowing courts to award no or reduced liquidated damages where the employer shows the violation was made in good faith and there were reasonable grounds for believing the act or omission was not a violation of the FLSA. States and localities have provided for additional damages to help ensure the price of violating substantially outweighs the cost of compliance. For example, the city of Los Angeles provides a penalty of $120 per day that the violation occurred or continued payable to each impacted employee, in addition to a fine payable to the city of $50 per day. See Los Angeles Municipal Code §§ 188.07(A) & 188.08(A). When compared to liquidated damages, daily penalties have the additional benefit of incentivizing violators to promptly correct the violation. Alternatively, states including Arizona, Idaho, Illinois, Massachusetts, New Mexico, Ohio, and Rhode Island have passed laws allowing for treble damages in minimum wage claims to impacted employees; Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Carolina, Vermont, and West Virginia allow for treble damages in other wage claims. See Galvin, “Deterring Wage Theft,” p. 336; National Employment Law Project, “Winning Wage Justice: An Advocate’s Guide to State and City Policies to Fight Wage Theft” (2011), available at https://www.nelp.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/WinningWageJustice2011.pdf.

75. In addition to treble damages, under Seattle law, the enforcement agency can assess a civil penalty of $500 per aggrieved party and a number of fines, including a fine of $500 per missing record for an employer’s failure maintain payroll records, payable to the agency. Unlike federal law, Seattle does not require that the violation be willful or repeated to assess these penalties and fines. Rather, Seattle has additional penalties for willful violations and tiered penalties for subsequent violations. See Seattle Municipal Code §§ 14.19.080(D)-(G).

76. Portal to Portal Pay Act, U.S. Code 29 § 260 (1947); U.S. Department of Labor, Field Assistance Bulletin No. 2020-2: Practice of Seeking Liquidated Damages in Settlements in Lieu of Litigation (2020), available at https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/WHD/legacy/files/fab_2020_2.pdf.

77. Where a violation is ongoing, statutes of limitations, or SOLs, may also determine how far back in time an aggrieved person can recover back pay for past violations. Thus, short SOLs can restrict the amount of time an agency can look back to remedy violations, which lets violating employers off the hook for longtime noncompliance. Further, in situations where workers are unaware of their rights, short SOLs can preclude agencies from acting on a complaint where the employee learned after the fact that an employment practice was illegal.