Race and the lack of intergenerational economic mobility in the United States

This essay is part of Vision 2020: Evidence for a stronger economy, a compilation of 21 essays presenting innovative, evidence-based, and concrete ideas to shape the 2020 policy debate. The authors in the new book include preeminent economists, political scientists, and sociologists who use cutting-edge research methods to answer some of the thorniest economic questions facing policymakers today.

To read more about the Vision 2020 book and download the full collection of essays, click here.

Overview

Intergenerational economic mobility—the likelihood that children achieve a higher standard of living than the household in which they were reared—varies considerably throughout the United States. In addition to the geographic variability of mobility, there also are significant racial and gender differences in mobility. Mobility, in short, is a complex nexus of individual, community, state, and national policies and circumstances.

Geographic and racial differences in economic mobility are particularly important from a policy perspective for three reasons. First, racial differences in mobility can exacerbate racial differences in other areas such as in housing, education, and health. Second, inequalities in opportunity are antithetical to our nation’s creed of equal opportunity for all. And third, structural differences in mobility limit the potential for overall U.S. economic growth.

Our essay first examines the historic links between intergenerational economic mobility and race and income inequality—trends heavily influenced by changing patterns in geographic mobility—and how these trends are tied to explicit policy decisions in the past that persist today in terms of housing, education, and health inequality among low- and middle-income black Americans. We then examine the known policy remedies for persistently low intergenerational economic mobility among African Americans and how these policies could be put into action and paid for. We recommend a mix of policies to promote more equitable housing and educational opportunities alongside moves to boost income security and wealth accumulation.

What we know about race and mobility in the United States

Past research on mobility revealed a strong relationship between parental economic circumstances and childrens’ socioeconomic outcomes in adulthood. Still, this research generally relied upon smaller population samples, with limited ability to discern geographic patterns in that data. More recent research has used administrative tax records to link parents and children, allowing us to explore intergenerational economic mobility with greater precision than ever before.

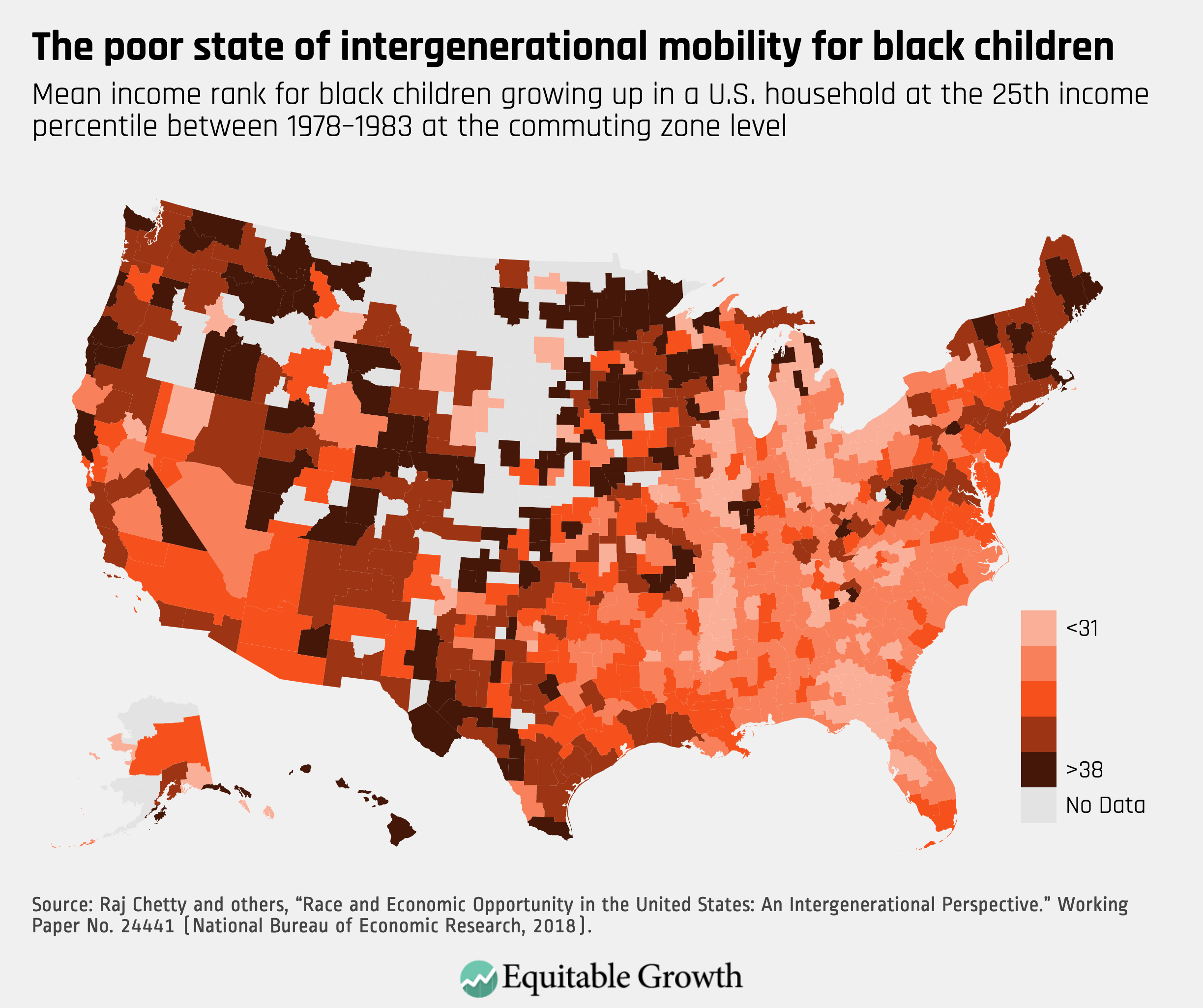

Scholars have long known that race is related to both intra- and intergenerational economic mobility—within a single generation and between multiple generations. Major research volumes have documented large black-white gaps in employment and incarceration, particularly among black males.1 Today, newer evidence demonstrates that the lack of black intergenerational income mobility is driven in large part by the extremely poor socioeconomic outcomes of black children, according to research by economist Raj Chetty and his colleagues at Harvard University. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Areas with large black population shares are also areas where black individuals experience particularly low levels of economic mobility, with black children born into below-median-income families tending to remain below the median income.2 For every 10 percentage point increase in the share of the black population in an area, the expected mean income rank of children drops by 0.7 percentage points. These differences exacerbate racial inequality in economic mobility.

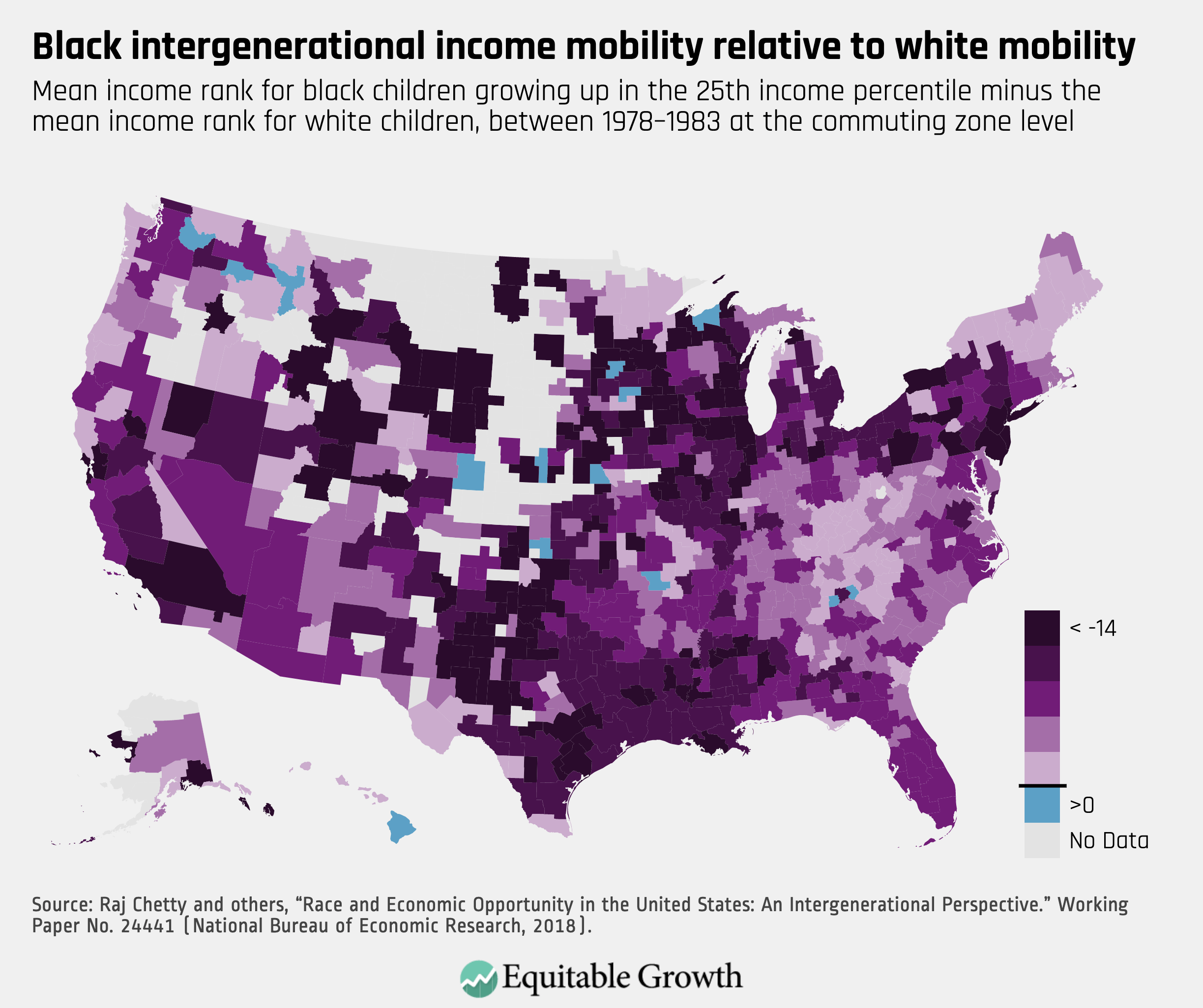

In nearly all areas of the country, the same mean income rank for black children from Figure 1 relative to white children is negative, suggesting that black children growing up in the 25th income percentile reach much lower rungs on the income ladder relative to white children growing up at the same income level in the same commuting zone. In other words, the racial differences in mobility amplify the geographic differences. (See Figure 2).

Figure 2

Research has documented several correlates of the large intergenerational mobility gap by race, each of which is important for policy. The presence of fathers is correlated with a lower black-white gap, as are marriage rates.3 And segregation, poverty, and education are all related to larger black-white gaps in mobility.4 Each of these underlying correlates is itself influenced by a number of existing policies, suggesting that changes in these policies could also change the trajectory of racial gaps in mobility.

But first, it’s important to understand that historic geographic mobility patterns overlay these economic inequality markers. Black mobility in earlier generations lagged white mobility in every area of the United States.5 The regions where the gap was largest, however, were quite different than they are today. In earlier generations, the South was the epicenter of racial inequality, while today, the South and the Northeast and Midwest are fairly indistinguishable with respect to racial inequality.

The process through which areas that once were more racially equitable but today are not is a complicated story of policy-driven choices that affected intergenerational mobility across the country. Recent research highlights that factors such as school segregation, disinvestment from public goods, and divergent levels of investment in education since the 1950s have combined to create a nexus of low mobility for blacks in general and for black men in particular.6

These correlates of intergenerational mobility reinforce what the policymaking community has long known about poverty, wealth formation, and public policy.7 Areas with higher levels of segregation have a range of features that contribute negatively to economic development, including lower investment in public goods, worse health outcomes, and longer commute times. Areas that had more entrenched redlining—federal policies that enforced segregation in homeownership—have larger racial gaps, not just in homeownership but also in wealth and earnings.

Indeed, recent research links the racial legacies of segregation, lynchings, and Confederate monuments in specific locations to present-day black-white wage gaps, suggesting that continuing racial animus may play a role in contemporary U.S. labor market outcomes.8 Similarly, geographic variation in publicly funded schools, social services, and access to enriching child development programs follows a racial demographic pattern. These factors within cities at the neighborhood-level combine with family-level circumstances to create more economic insecurity. When taken together, many children face an array of adverse neighborhood, school, and family-level factors that are harmful for development and potentially impede upward social and economic mobility.9

The evidence that policy interventions can improve mobility

The crisis of intergenerational poverty and low socioeconomic outcomes among black Americans must be properly contextualized. Many black Americans have succeeded in the face of substantial adversity and labor market discrimination—and in spite of limited access to wealth, networks, connections, and educational opportunities. Still, exceptionalism in the face of adversity is not a sufficient policy prescription.

Fortunately, we know quite a bit about how to raise socioeconomic outcomes. As noted above, policies that improve upon the overall quality of neighborhoods—including schooling, safety, and housing quality—have been shown to raise the eventual adult socioeconomic outcomes of children.10 Second, a relatively contemporary body of evidence confirms the positive impacts of higher school expenditures on fighting poverty and improving economic opportunities.11 And large-scale expansion of safety net programs such as supplemental nutrition assistance and financial assistance for needy families lowered poverty and improved socioeconomic outcomes.12

In addition, reforms within the U.S. higher education and workforce training systems have, in specific instances and regions, provided career training and subsequent employment opportunities via a commitment between employers, educational institutions, and student trainees. Such efforts, if scaled up to meet the needs of low- and middle-income African Americans today, could help to overcome the relatively lower levels of social capital, the labor market bias, and the discrimination that many black Americans face.13

For many families, wealth operates as a primary mechanism that unlocks access to the nation’s best neighborhoods, along with the full range of amenities that this entails. Wealth also provides a buffer in the event of adverse and unanticipated negative economic shocks, which are more likely to occur among black families. Wealth gaps have very clear implications for upward mobility, including educational attainment and occupation status.14 Wealth promotes enriching opportunities, while also cushioning against a range of events that can derail households, including health shocks, relationship changes, and job loss.

Black Americans largely lack high levels of wealth to unlock opportunity. Most also operate without even emergency levels of savings or access to credit needed to withstand unanticipated shocks. Accordingly, policy solutions that provide greater liquidity and wealth to black Americans have the potential to greatly improve intergenerational economic mobility.

Translating the evidence into policy

The importance of neighborhoods cannot be understated. Many Americans across the political spectrum remain resistant to racial and economic integration, which means the prospect of a large-scale economic integration program shifting low- and middle-income income black families into relatively affluent neighborhoods seems unlikely. But a “second-best” set of solutions still could attack the root causes of racial differences in intergenerational economic mobility.

First and foremost, enforcement of anti-discrimination lending policies, aggressive affordable housing policies, and more equitable education finance policies would work to improve access to affordable, safe, quality housing. Efforts at the state and local level could provide support for land trusts, which preserve affordable housing for low- and moderate-income residents by removing housing land from the marketplace—typically facilitated via purchases and land donations from philanthropic and nonprofit organizations15—and longer-term agreements between local governments and housing developers to maintain home affordability.

Policymakers also could reconsider the efficacy of public housing, including whether and how such housing can be improved and maintained and whether mixed-income arrangements resulting in a net-loss of low-income housing should provide cautionary lessons moving forward. Because housing across most of the country is taking an increasingly high share of income among even middle-class families, efforts to address affordable housing via neighborhood improvements could have spillover benefits for many middle-class families, irrespective of race.

Additional educational expenditures also have been shown to improve student outcomes and so should be taken seriously. Such expenditures should also expand social and employment services available within primary and secondary educational settings.16 In this way, policymakers could better direct resources toward families and aggressively target the link between income and educational achievement.

Promoting wealth accumulation and greater access to credit for low-income black families also would promote opportunity, while cushioning against adverse events. One innovative policy option is the issuance of Baby Bonds.17 These proposed new bonds would give children an asset account predicated on the wealth of their parents. In adulthood, the child would have access to those resources to engage in wealth-enhancing activities such as postsecondary schooling, purchasing a home, or financing entrepreneurial activity.18 By design, Baby Bonds close a significant portion of the wealth gap between black and white households.

Another set of options include reforms to the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program to expand expenditures on cash benefits.19 This reform would enable low-income families of any race to have greater access to needed liquidity.20 Such interventions are most effective if targeted toward economically disadvantaged and racially segregated neighborhoods, including rural areas.21

Finding the revenue for these reforms

The suggestions put forth above do not come without a cost, though we believe the societal benefits of intervening outweigh the costs of inaction. Thus, another needed “prescription” includes increased tax revenue at the federal and state level to help break the transmission of poverty across generations.22 As hard as this may seem, the politics required to make these investments seems more likely than large-scale racial integration and the transition of low-income black Americans into more affluent and safer neighborhoods with higher-quality schools.

Indeed, the tax system is perhaps the main vehicle to promote redistribution, to reduce black-white income and wealth gaps. While many tax policies provide important benefits to black households, the tax system also provides an array of deductions and benefits that favor wealth over income, potentially worsening racial economic inequality.23

Download FileRace and the lack of intergenerational economic mobility in the United States

Why policymakers should intervene to improve intergenerational mobility

There is a moral argument for intervening on behalf of low-income black Americans, many of whom remain mired in intergenerational poverty, alongside an efficiency rationale for the broader U.S. population. The data from Harvard’s Chetty and his co-authors can be interpreted many ways. One view is that middle-class families, including many white families, are paying for disinvestment in poor, predominantly black neighborhoods.24 How so? Many of America’s cities have clear defining lines, within which lie reliable police protection and low crime, a rich array of private amenities, and higher-quality public and private school choices. The disinvestment in poor, predominantly minority-inhabited neighborhoods therefore bids up the value of “preferred” locations that are in limited supply.

The upshot: Investments that improve school quality, lower crime, and encourage private-sector amenities will have positive spillovers by creating a wider set of quality housing alternatives. Most American families have not experienced substantial wage growth over the past several decades. Lowering housing costs—and therefore reducing the amount each family must spend on housing costs every month—will ease pressures on take-home pay. Of course, such investments will make it all the more important to maintain spaces for low-income families as such places become more desirable.

What’s key, though, is that improvements to the overall neighborhood infrastructure in the poorest neighborhoods around our country—which are disproportionately black and minority inhabited—would improve the well-being of poor Americans of all races and provide affordable housing and schooling alternatives for middle-class families of all races. More robust intergenerational mobility in the future, for black Americans in particular, would be the end result.

—Bradley Hardy is an associate professor of public administration and policy at American University. Trevon Logan is the Hazel C. Youngberg Trustees Distinguished Professor of Economics at The Ohio State University and a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research.

End Notes

1. See, for example, scholarly volumes focused on labor market conditions of black Americans and black men. Richard B. Freeman and Harry J. Holzer, eds. The Black Youth Employment Crisis (New York: University of Chicago Press, 1986); Ronald B. Mincy, Black Males Left Behind (New York: Rowan and Littlefield, 2006).

2. In counties with a majority black population, a black child born to parents in the 25th income percentile only achieves a mean income rank of 32, barely any movement up the income ladder, while for white children from the same counties achieve a mean income rank of 43.

3. Raj Chetty and others, “Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective.” Working Paper No. 24441 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2018).

4. Ibid.

5. David Card, Ciprian Domnisoru, and Lowell Taylor, “The Intergenerational Transmission of Human Capital: Evidence from the Golden Age of Upward Mobility.” Working Paper No. 25000 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2018).

6. Ellora Derenencourt, “Can You Move to Opportunity? Evidence from the Great Migration.” Working Paper (Harvard University, 2019).

7. Bradley Hardy, Trevon D. Logan, and John Parman, “The Historical Role of Race and Policy for Regional Inequality.” In Jay Shambaugh and Ryan Nunn, eds., Placed Based Policies for Shared Economic Growth (Washington: The Brookings Institution, 2018).

8. Jhacova Williams, “Historical Lynchings and the Contemporary Voting Behavior of Blacks.” Working Paper (Clemson University, 2019); Jhacova Williams, “Confederate Streets and Black-White Labor Market Differentials.” Working Paper (Clemson University, 2019); Rodney J. Andrews and others, “Location Matters: Historical Racial Segregation and Intergenerational Mobility,” Economics Letters 158 (2017): 67–72.

9. Bradley L. Hardy, Heather D. Hill, and Jennie Romich, “Strengthening Social Programs to Promote Economic Stability during Childhood,” forthcoming (Washington: SRCD, 2019).

10. Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, and Lawrence F. Katz, “The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment,” American Economic Review 106 (4) (2016): 855–902.

11. C. Kirabo Jackson, Ricker C. Johnson, and Claudia Persico, “The Effects of School Spending on Educational and Economic Outcomes: Evidence from School Finance Reforms,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 131 (1) (2016): 157–218.

12. Hilary Hoynes, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, and Douglas Almond, “Long-Run Impacts of Childhood Access to the Safety Net,” American Economic Review 106 (4) (2016): 903–934.

13. For a discussion of such partnerships and how these may buffer against low levels of information and social capital among many college students, see Harry J. Holzer and Sandy Baum, Making College Work: Pathways to Success for Disadvantaged Students (Washington: Brookings Institution Press, 2017).

14. Fabian T. Pfeffer, “Status Attainment and Wealth in the United States and Germany.” In Thomas Smeeding, R. Erikson, and M. Jantti, eds., Persistence, Privilege, and Parenting: The Comparative Study of Intergenerational Mobility (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2011).

15. M. Choi, S. Van Zandt, and D. Matarrita-Cascante, “Can community land trusts slow gentrification?,” Journal of Urban Affairs 40 (3) (2018): 394–411.

16. Helen Ladd, “Education and Poverty: Confronting the Evidence,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 31 (2) (2012): 203–227.

17. W.Darity Jr. and D. Hamilton, “Bold policies for economic justice,” The Review of Black Political Economy 39 (1) (2012): 79–85.

18. Darrick Hamilton, “Race, Wealth, and Intergenerational Poverty,” The American Prospect, August 14, 2009, available at https://prospect.org/article/race-wealth-and-intergenerational-poverty.

19. Marianne Bitler and Hilary Hoynes, “The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same? The Safety Net and Poverty in the Great Recession,” Journal of Labor Economics 34 (s1) (2016): S403–S444.

20. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, “Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2018 – May 2019” (2019); I. Floyd, “Despite Recent TANF Benefit Boosts, Black Families Left Behind” (Washington: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2018); B.L. Hardy, R. Samudra, and J.A. Davis, “Cash Assistance in America: The Role of Race, Politics, and Poverty,” The Review of Black Political Economy (2019).

21. James P. Ziliak, “Restoring Economic Opportunity for ‘The People Left Behind’: Employment Strategies for Rural America” (Washington: Aspen Institute, 2019).

22. For a discussion of the role of tax policy and the need for higher revenues to reinvest in America’s children, see William G. Gale, Fiscal Therapy: Curing America’s Debt Addiction and Investing in the Future (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019).

23. Chye-Ching Huang and Roderick Taylor, “How the Federal Tax Code Can Better Advance Racial Equity” (Washington: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2019).

24. P. Bayer and others, “Ethnic and Racial Price Differentials in the Housing Market,” Journal of Urban Economics (102) (2017): 91–105.