Must- and Shall-Reads:

- : “There’s no evidence that we are having a technology renaissance right now, or that technology has contributed in a major way to the weak recovery, or that a skills gap or other educational factor is holding back employment, or that highly skilled workers are having a great time in the labor market…

- : How Inequality Harms Health–and the Economy

- : “The February employment report almost certainly means the Fed will no longer describe its policy intentions as ‘patient’ at the conclusion of the March FOMC meeting. And it also keep a June rate hike in play. But for June to move from ‘in play’ to ‘it’s going to happen,’ I still feel the Fed needs a more on the inflation side…”

- : “A change in institutions towards ones that reduce the wage premium should also increase the hours premium…. Both periods of compression in the 1930s and the 1940s, then, seem to fit the pattern of institutions rather than supply-and-demand…”

- : Picking Winners? Investment Consultants’ Recommendations of Fund Managers

-

: This Will Be The GOP Congress’ Last Chance For Salvation: “[In] the debate on the congressional budget resolution… neither of the two procedural impediments that stopped the GOP dead in its tracks on DHS will exist. That will give congressional Republicans the only chance they may get all year to impose their preferences…. Budget resolutions can’t be filibustered… [are] a concurrent resolution…. In theory, therefore… both houses [should] adopt a Republican-preferred version of a budget resolution…. But… it’s not obvious that any budget resolution acceptable to Senate Republicans will go far enough to appease the House GOP…. This will be the GOP Congress’ best… opportunity…. If they can’t even agree on a budget, it will be the GOP itself that is to blame and damnation will likely be ahead.” -

(2011): Barnard College Commencement: “Women all over the world, women who are exactly like us except for the circumstances into which they were born, [lack] basic human rights. Compared to these women, we are lucky…. We are equals under the law. But the promise of equality is not equality…. Men run the world…. I recognize that [today] is a vast improvement from generations in the past…. But… women became 50% of the college graduates in this country in 1981, 30 years ago. Thirty years is plenty of time for those graduates to have gotten to the top of their industries, but we are nowhere close to 50% of the jobs at the top. That means that when the big decisions are made, the decisions that affect all of our worlds, we do not have an equal voice at that table. So today, we turn to you. You are the promise for a more equal world…. Only when we get real equality in our governments, in our businesses, in our companies and our universities, will we start to solve… gender equality. We need women at all levels, including the top, to change the dynamic, reshape the conversation, to make sure women’s voices are heard and heeded, not overlooked and ignored…” -

: Stagflation Predictions: “Matt O’Brien catches a piece by Dick Morris a few years ago predicting that Obama’s legacy would be stagflation. But I say, oh yeah? I’ll see your Dick Morris (who cares, really?) and raise you a… Paul Ryan: ‘Thirty Years Later, a Return to Stagflation.’ That was, if you check the date, six years ago. But it’s worth remembering that not all prominent Republicans were predicting 70s-style stagflation; some of them were predicting Weimar-style hyperinflation instead…” -

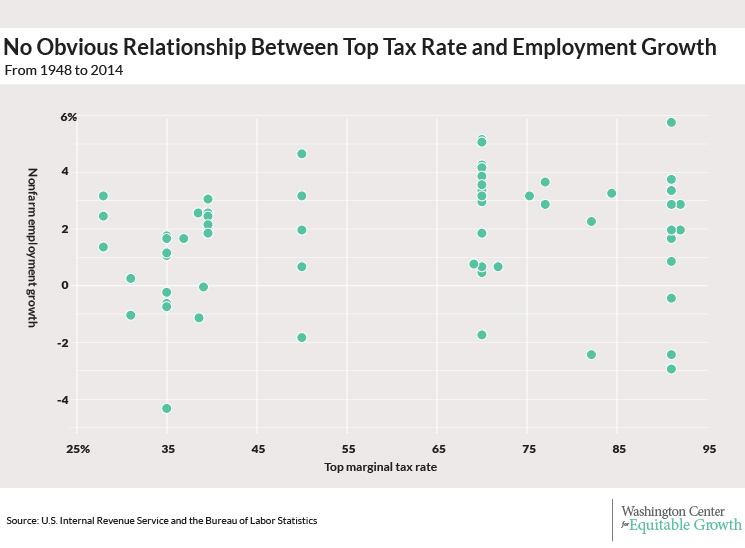

: Weekend Reading: “Mike Konczal on… rebalanc[ing] ‘our intellectual portfolio of inequality stories.’ ATMs… [are not] technology displacing labor… reduce wealth inequality… by tax[ing] land… broken workers’ comp… France… family-friendly policies… no obvious relation between top tax rate and employment growth”

Should Be Aware of:

- : “tl;dr: you can’t do it today. and i think you should be able to…”

- : “The JALSA argument is… (1) The plaintiffs’ interpretation might be unconstitutional. (2) The question… would be hard to resolve. And (3) a holding for the government would… avoid the hard question… [hence] the specter of unconstitutionality is a good reason not to venture in the plaintiffs’ direction…”

- The Uttermost West, Before the Thrones of the Valar, in the Timeless Halls

- : Many Worlds, the Born Rule, and Self-Locating Uncertainty

-

: You Can’t Spell “Reformicon” Without “Con”: “Remember when Republicans were totally going to be the Party of Ideas (TM) because a small group of conservative intellectuals with little discernible influence on Republican legislators thought that George W. Bush-style supply side politics should be supplemented by some feints towards the middle class? Well, funny thing about that. Reformocon darlings Mike Lee and Marco Rubio have taken their massive regressive tax cut and made it… much, more more regressive, eliminating taxes on investment and inherited income entirely. So are reformocons upset about the betrayal? Is the Pope a Seventh Day Adventist? “Perhaps the fullest measure of the supply-siders’ triumph can be seen in the acquiescence of many of the reformicons themselves. Ramesh Ponnuru and Yuval Levin, both reform conservatives featured prominently in the Times story, responded to the new Lee-Rubio plan with fawning praise. James Pethokoukis, a reformist conservative, calls the plan “a big step toward persuading middle-income America that Republicans care about more than just the richest 1 percent.” (If this is a big step toward persuading America that Republicans care about more than the rich, what would the next step be? Legalizing servant-flogging?) Perhaps the reform conservatives have capitulated completely in the name of party unity. Or maybe they were misunderstood from the beginning and never proposed to deviate in any substantive way from the traditional platform of massively regressive, debt-financed tax-cutting. Either way, the movement has, for now, accomplished less than nothing.’ But, gee, I can’t wait to hear their alternative health care proposal!” -

: Forward Under 40: Trevon Logan ’99: “It’s no wonder that Trevon Logan was unanimously selected as co-chair of his Chancellor’s Scholars class at UW-Madison for three years in a row. His classmates knew even then: Logan was the sort of leader who inspired everyone to do their best. Today Logan is an award-winning teacher and scholar who recently became the youngest-ever president of the National Economic Association. He has also led several national initiatives to increase diversity in his field…” -

(2012): 13 Ways of Looking at Medium: “The individual sought self-expression and an audience; the organization sought sustainability and cash money…. Facebook built a way for people to express themselves… to… their self-defined network of friends…. Twitter… built a way for people to express themselves, in a format that was genius in its limitations and in its old-media model of subscribe-and-follow…. Tumblr, Path, Foursquare, and a gazillion others have tried to pull off the same trick: Serve users by helping them find an outlet for personal expression, then build a business…. Medium… degrades authorship… is built around collections, not authors…. The author is there as a reference point to an identity layer–Twitter–not as an organizing principle…. Medium wants you to read something because of what it’s about. And because of the implicit promise that Medium = quality…. Medium believes in editorial judgment–but everyone’s an editor…. The tension between what’s good and what’s new is a long-standing one for online media, and privileging either comes with drawbacks…” -

: The Next Internet Is TV: “Some of the most visible companies in internet media are converging…. Vox is now publishing directly to social networks and apps; BuzzFeed has a growing team of people dedicated to figuring out what BuzzFeed might look like without a website at the middle. Vice, already distributing a large portion of its video on Google’s YouTube, has a channel in Snapchat’s app, along with CNN, Comedy Central, ESPN, Cosmo and the Daily Mail…. Websites are unnecessary vestiges of a time before there were better ways to find things to look at on your computer or your phone. What happens next?… The gaps left by the websites we stop looking at will be filled with new things, and most people won’t really notice the change until it’s nearly done…. The grand weird promises of writing and reporting and film and art on the internet [will] consolidate… into a set of business interests that most closely resemble the TV industry…. Wasn’t the internet supposed to be BETTER, somehow, in all its broken decentralized chaos and glory? The TV industry, which is mediated at every possible point, is a brutal interface for culture and commerce…”