For economies at the the zero lower bound on safe nominal short-term interest rates, in the presence of a Keynesian fiscal multiplier of magnitude μ–now thought, for large industrial economies or for coordinated expansions to be roughly 2 and certainly greater than one–an extra dollar or pound or euro of fiscal expansion will boost real GDP by μ dollars or pounds or euros. And as long as the interest rates at which the governments borrow are less than the sum of the inflation plus the labor-force growth plus the labor-productivity growth rate–which they are–the properly-measured amortization cost of the extra government liabilities is negative: because of the creation of the extra debt, long-term budget balance allows more rather than less spending on government programs, even with constant tax revenue.

Production and employment benefits, no debt-amortization costs as long as economies stay near the zero lower-bound on interest rates. Fiscal stimulus is thus a no-brainer, right?

Perhaps you point to a political-economy risk that should economies, for some reason, move rapidly away from the zero lower bound their governments will not dare make the optimal fiscal-policy adjustments then appropriate. But future governments that wish to pursue bad policies no matter what we do today. And offsetting this vague and shadowy political-economy risks is the very tangible benefit that fiscal expansion’s production of a higher-pressure economy generates substantial positive spillovers in labor-force skills and attachment, in business investment and business-model development, and in useful infrastructure put in place.

Truly a no-brainer. The only issue is “how much?” And that is a technocratic benefit-cost calculation. Rare indeed these days is the competent economist who has thought through the benefit-cost calculation and failed to conclude that the governments of the United States, Germany, and Britain have large enough multipliers, strong enough spillovers of infrastructure investment and other demand-boosting programs, and sufficient fiscal space to make substantially more expansionary fiscal policies optimal.

This is the backdrop against which we today find aversion to fiscal expansion being driven not by pragmatic technocratic benefit-cost calculations but by raw ideology. And so we find my one-time teacher and long-time colleague Barry Eichengreen https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/monetary-policy-limits-fiscal-expansion-by-barry-eichengreen-2016-03 being… positively shrill: While “the world economy is visibly sinking”, he writes:

the policymakers… are tying themselves in knots… the G-20 summit… an anodyne statement…. It is disturbing to see… particularly… the US and Germany [refusing] to even contemplate such action, despite available fiscal space…. In Germany, ideological aversion to budget deficits… rooted in the post-World War II doctrine of ‘ordoliberalism’… [that] rendered Germans allergic to macroeconomics…. [In] the US… citizens have been suspicious of federal government power, including the power to run deficits… suspicion… strongest in the American South…. During the civil rights movement, it was again the Southern political elite… antagonistic to… federal power…. Welcome to ordoliberalism, Dixie-style. Wolfgang Schäuble, meet Ted Cruz.

Barry, faced with the triumph of sterile austerian ideology over practical technocratic economic stewardship, concludes with a plea:

Ideological and political prejudices deeply rooted in history will have to be overcome…. If an extended period of depressed growth following a crisis isn’t the right moment to challenge them, then when is?

Barry will continue to teach the history. He will continue to teach that expansionary fiscal and monetary policies in deep depressions have worked very well, and that eschewing them out of fears of interfering with “structural adjustment” has been a disaster. But this is no longer, if it ever was, an intellectual discussion or debate.

So perhaps there is a flanking move possible. “Monetary policy” and “fiscal policy” are economic-theoretic concepts. There is no requirement that they neatly divide into and correspond to the actions of institutional actors.

German, American, and British austerians have a fear and suspicion of central banks that is rooted in the same Ordoliberal and Ordovolkist ideological fever swamps as their objections to deficit-spending legislatures. But it is much weaker. It is much weaker because, as David Glasner points out, fundamentalist cries for an automatic monetary system–whether based on a gold standard, on Milton Friedman’s k%/year percent growth rule, or John Taylor’s mandatory fixed-coefficients interest-rate rule–have all crashed and burned so spectacularly. History has refuted Henry Simons’s call for rules rather than authorities in monetary policy. The institution-design task in monetary policy is not to construct rules but, instead, to construct authorities with sensible objectives and values and technocratic competence.

And central banks can do more than they have done. They have immense regulatory powers to require that the banks under their supervision to hold capital, lend to previously discriminated-against classes of borrowers, and serve the communities in which they are embedded as well as returning dividends to their shareholders and making the options of their executives valuable. And they have clever lawyers.

Their policy interventions have always been “fiscal policy” in a very real sense. They collect the tax on the economy we call “seigniorage”. There is no necessity that they turn their seigniorage revenue over to their finance ministries. Their interventions have always altered the present value of future government principal and interest payments.

Mid nineteenth-century British Whig Prime Minister Robert Peel was criticized by many for putting too-tight restrictions on crisis action in the Bank of England’s recharter. His response was that the new charter was written to cover eventualities that people could foresee. But that should eventualities occur that had not been foreseen, the only hope was for there then to be statesmen who were willing to assume the grave responsibility of dealing with the situation. And that he was confident there would be such statesmen.

Yes, it is time for central bankers to assume responsibility and undertake what we call “helicopter money”.

It could take many forms. It depends on the exact legal structure and powers of the central banks. It also depends on the extent to which central banks are willing, as the Bank of England did in the nineteenth century, to undertake actions that are not intra but ultra vires with the implicit or explicit promise that the rest of the government will turn a blind eye. The key is getting extra cash into the hands of those constrained in their spending by low incomes and a lack of collateral assets. The key is doing so in a way that does not lead them to even a smidgeon of fear that repayment obligations have even a smidgeon of a possibility of becoming in any way onerous.

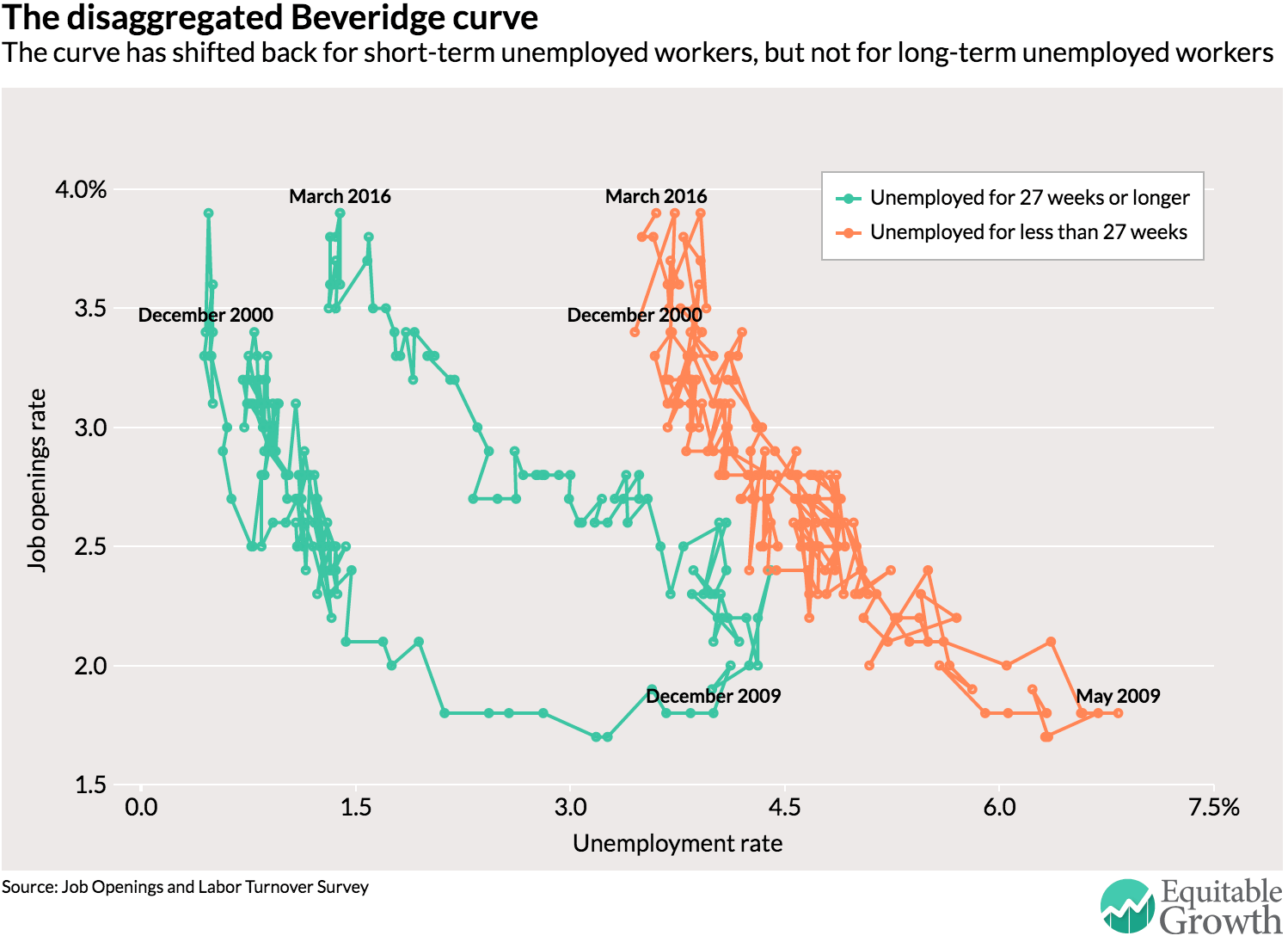

Figure from “

Figure from “