New research shows the importance of worker power for addressing U.S. wage inequality

Workers in the United States over the past 40 years experienced stagnant real wages for those at the lower end of the income distribution, along with rising income inequality, even as productivity rose. Some economists and policymakers argue these poor labor market outcomes are the unavoidable result of competitive markets, globalization, and technological advancement. Yet there is compelling evidence these negative outcomes for U.S. workers are due to policies that lower labor standards and structurally weaken workers’ bargaining power.

Indeed, not all countries experienced these patterns of declining wage quality and rising inequality, as demonstrated in two recent working papers from economist David Howell, an Equitable Growth grantee and a member of Equitable Growth’s Research Advisory Board. Howell’s latest research provides additional evidence that not only are U.S. wage outcomes exceptionally poor when viewed alongside outcomes in similar countries, but they are also a consequence of more than four decades of political choices.

In his first working paper, “How Exceptional is American Job Quality? The Incidence of Decent- and Poverty-Pay Jobs in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and France,” Howell compares earnings quality for workers by age, gender, and education in five countries—the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and France—over time.

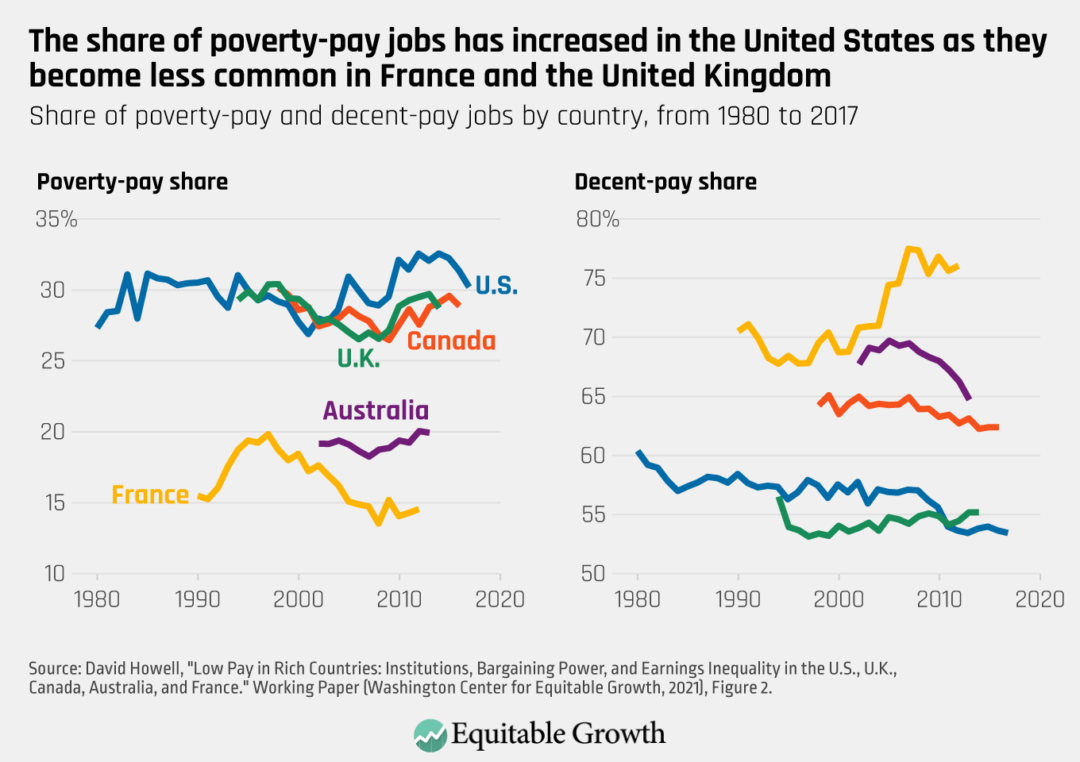

Howell finds that other countries—most notably France—show higher and often increasing shares of workers in “decent-pay” jobs, compared to the United States. He also finds that the share of “poverty-pay” jobs is highest for the United States, accounting for 30.2 percent of workers in 2017. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

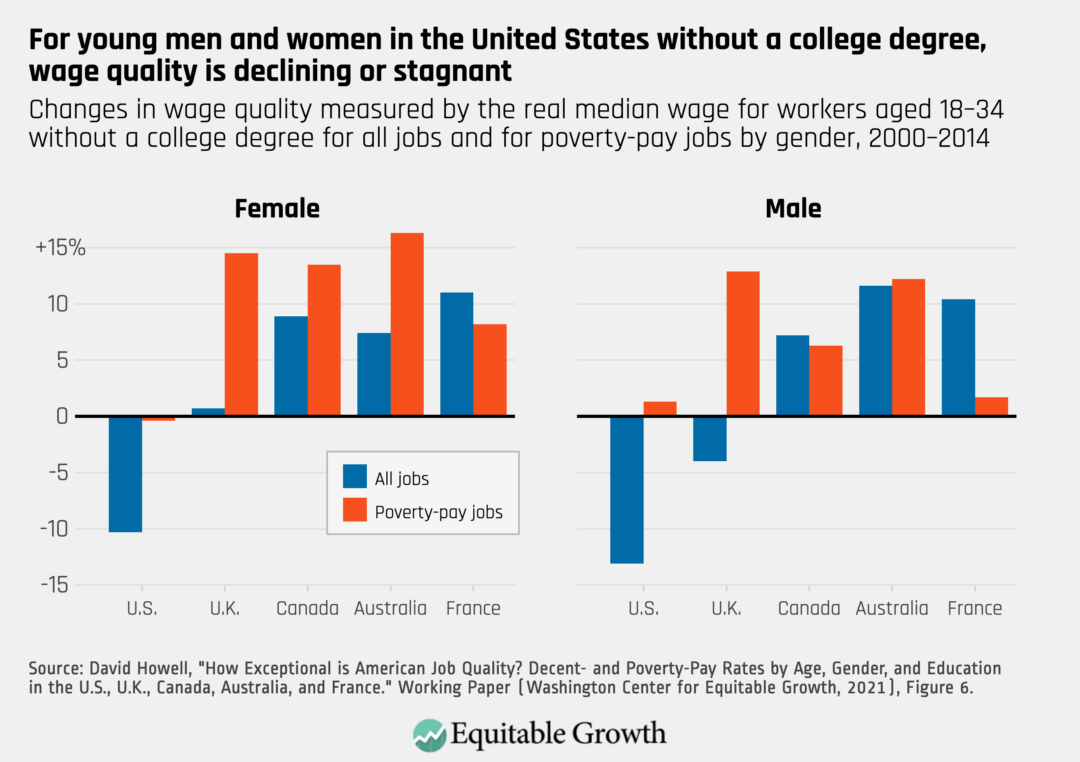

Some economists propose that recent technological advances reduced opportunities for U.S. workers with lower levels of education, and this is the key factor driving down wages for this group. But Howell finds that while wage outcomes in the United States since 2000 became worse for young workers without a college degree, the wage quality for similar workers in other countries actually rose over that same time period. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

In a second new working paper, “Low Pay in Rich Countries: Institutions, Bargaining Power, and Earnings Inequality in the U.S., U.K., Canada, Australia and France,” Howell further explores these pay patterns in the context of these countries’ approaches to labor protections, wage setting, and social policies that strengthen worker power.

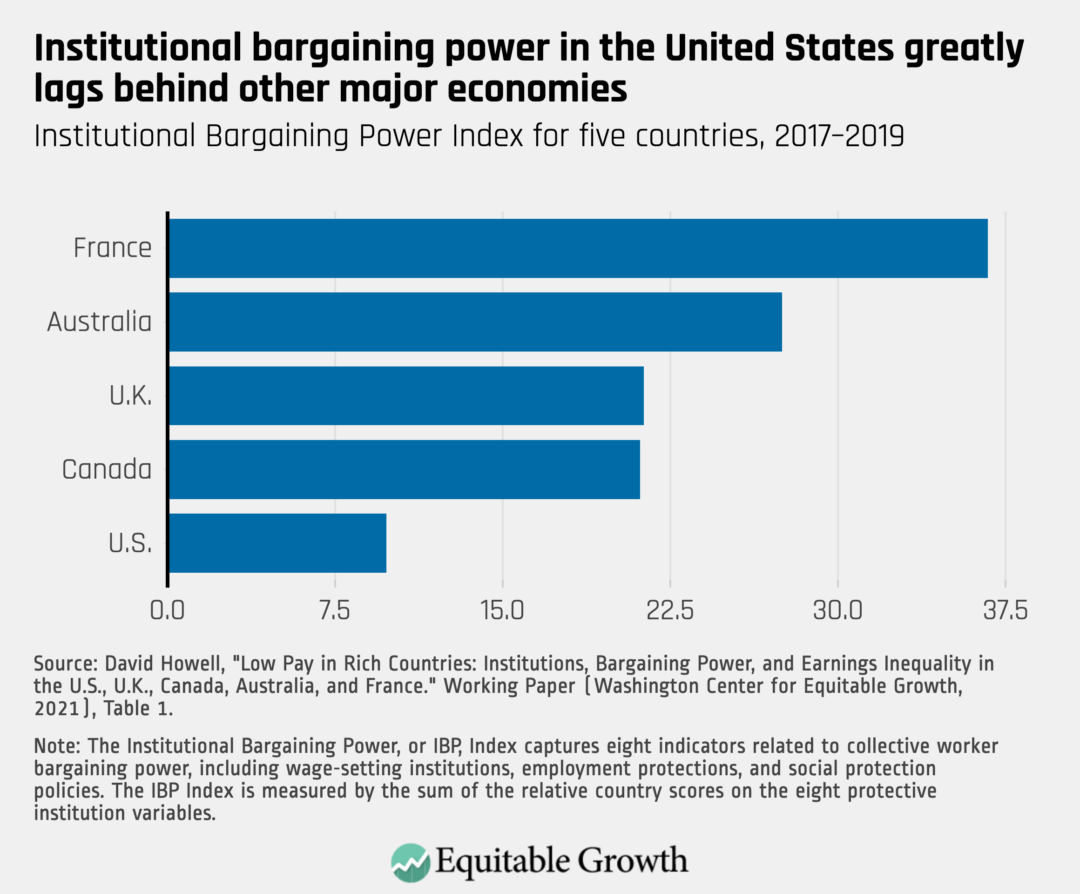

To compare worker power across countries, Howell created an Institutional Bargaining Power Index that captures various measures of collective bargaining coverage, national minimum wages, employment protection, and income supports. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

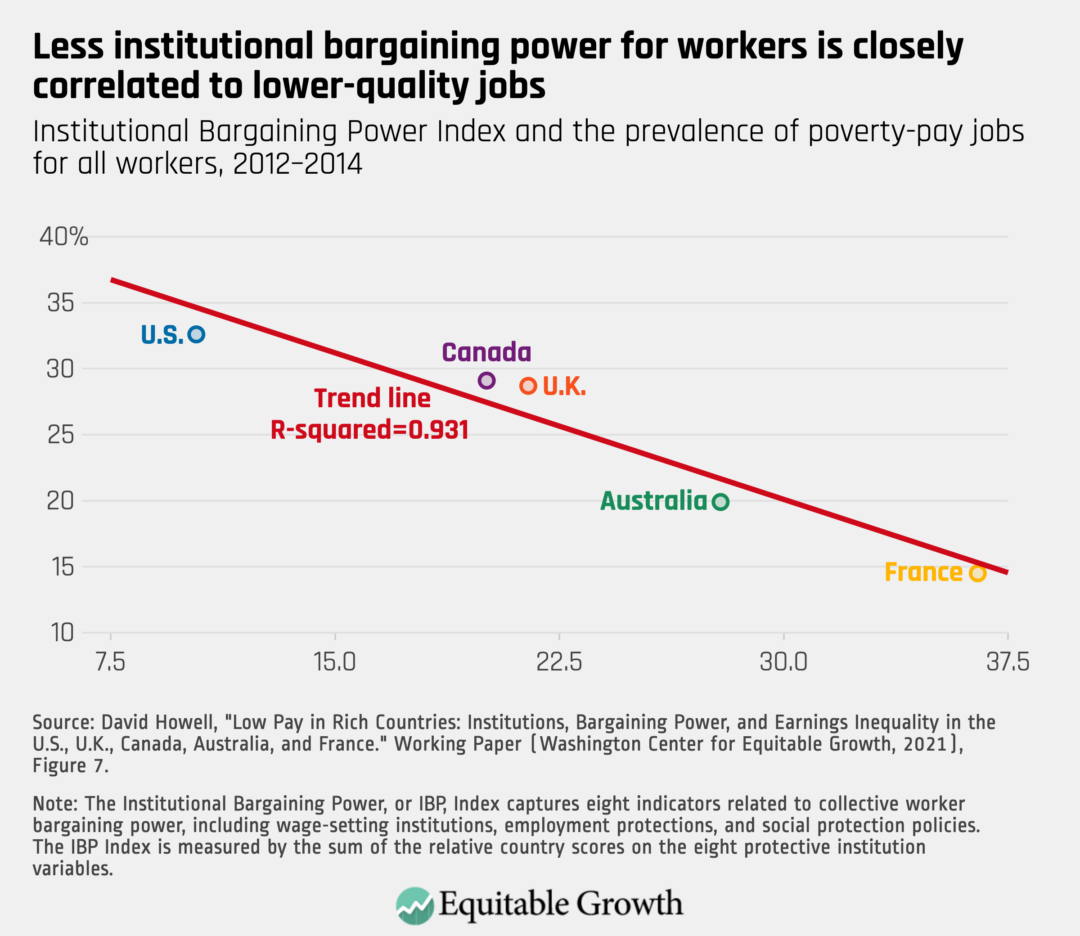

Howell finds that differences in countries’ institutional bargaining power explain a great deal of the differences in pay patterns between countries. This supports evidence from other research showing the importance of strengthening workers’ bargaining power and counteracting uncompetitive wage-setting practices by U.S. employers, which otherwise depress wages, increase inequality, and contribute to racial and gender pay divides. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

These patterns are even more striking for younger workers with lower levels of education. The United States has the lowest score on the Institutional Bargaining Power Index and the highest levels of poverty-pay jobs for both young women (70.1 percent) and young men (57.1 percent) who do not have college degrees. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

Conclusion

Howell’s two working papers demonstrate the ways in which bargaining power shapes economic outcomes in the United States, compared to other peer economies. His findings further buttress the evidence that U.S. workers’ economic gains are not merely defined by individual characteristics, such as education, or broader trends, such as globalization and technological advances.

U.S. policymakers need to empower unions and collective action so that when U.S. workers experience the ups and downs of economic trends, they can share in the gains of the economic growth to which they contribute. U.S. policymakers also need to invest in the nation’s critical social infrastructure so that U.S. workers and their families can be more productive and improve their well-being and the productivity and well-being of future generations.