New research finds enhanced U.S. social insurance will be necessary until the coronavirus recession recedes

A new working paper released by Harvard University economist and former Equitable Growth Steering Committee member Raj Chetty and his Opportunity Insights colleagues finds that U.S. consumer spending fell dramatically over the past few months, driven by public health and safety concerns due to the novel coronavirus and COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus. These concerns are keeping people, especially those in high-income households, away from purchasing in-person services, indicating that until people feel safe engaging again in in-person services such as dining out or getting haircuts, consumer spending on services—which accounts for 66 percent of all consumer spending—will not meaningfully rebound.

In short, if policymakers want to fix the U.S. economy, then they must first fix the U.S. public health crisis. Merely announcing that the economy is “reopened” will not make it so. In the meantime, Chetty and his co-authors find that investing in social insurance programs—such as the expanded unemployment benefits enacted by Congress in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act—is the best way to mitigate economic suffering during the recession, rather than stimulus measures targeted toward businesses or the rich.

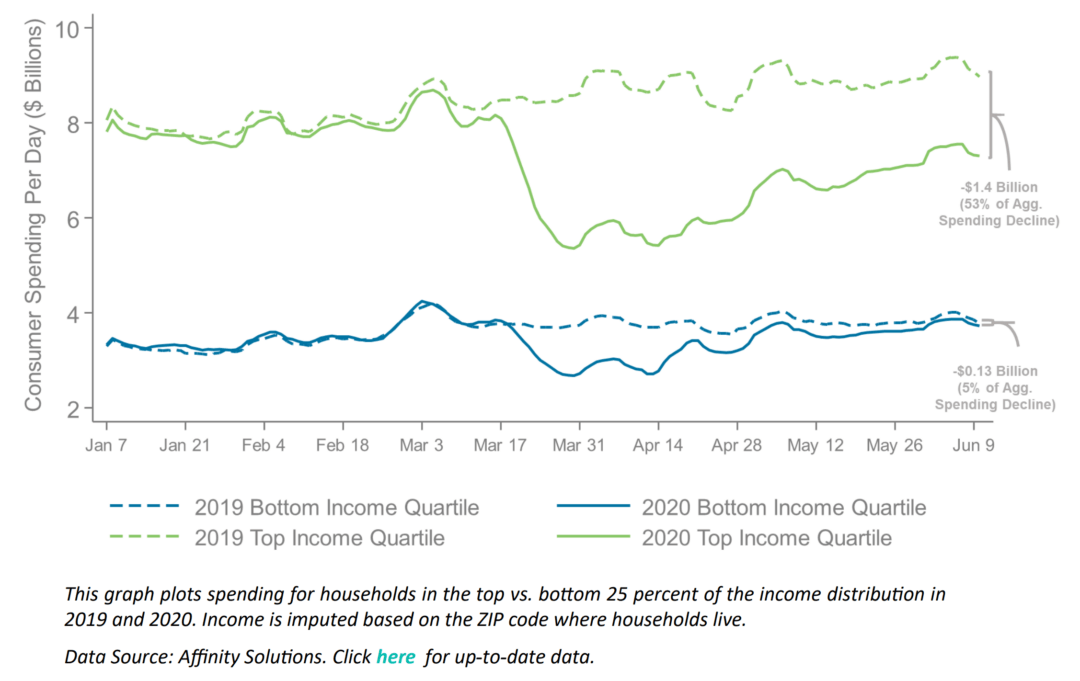

One of the key findings underlying the conclusions in this latest research is that the fall-off in consumer spending is being driven by high-income households, particularly in areas with high rates of COVID-19. The authors find that as of May 31, two-thirds of the total reduction in credit card spending since January was from households in the top 25 percent of the income distribution, whereas spending by households in the bottom quartile had returned to normal levels. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

High-income U.S. households have cut back sharply on spending

Consumer spending changes during the coronavirus recession, by income group, January 2020–June 2020

This fall-off in spending by the highest-income households is not driven by a decrease in their incomes, but rather because of the decline in in-person services they’re buying, such as dining out, traveling, or haircuts. The authors find that spending on other services and luxury goods that do not require in-person contact—such as the installation of home swimming pools or landscaping services—actually increased slightly since the onset of coronavirus pandemic. This strongly suggests that public health concerns about contracting the novel coronavirus are driving the changes in spending patterns among the highest-income households, which also are more likely to have the luxury of working from home and maintaining self-isolation.

The findings by Chetty and his co-authors should come as no surprise because of what we already know about the differences in spending and savings patterns among low- and high-income households. Research by Harvard University economist and Equitable Growth Steering Committee member Karen Dynan and her co-authors finds that while Americans, on average, save about 20 cents of every dollar they earn and spend the rest, those in the top 5 percent save 37 cents, and those in the top 1 percent save 51 cents. Meanwhile, those in the bottom 20 percent save only one cent of every dollar. That’s because higher-income households earn enough money to actually be able to put some of it aside in savings.

In contrast, because of rising inequality, stagnant wages, and deteriorating public institutions, low-income households have to spend all their income just meeting their basic needs—paying rent, putting food on the table, and securing childcare. Additionally, we know that lower-wage workers’ accumulated savings don’t amount to much of a cushion. Research from the Federal Reserve shows that 40 percent of U.S. adults would have a hard time handling an unexpected bill of $400. The Opportunity Insights research builds on this scholarship by demonstrating that there was less of a coronavirus-related fall-off in low-income households’ spending because there were no fancy restaurant dinners out or Broadway theater tickets to eliminate from their budgets in the first place.

The trend in low-income households’ spending, falling during the second half of March and then gradually returning to close to its original level, is also evidence of the success in government efforts to help replace low-income households’ lost income from coronavirus-related job layoffs. Chetty and his co-authors find that in the week after April 15, when the $1,200 checks enacted by Congress in the CARES Act hit most Americans’ bank accounts, spending by the bottom quartile of households increased by nearly 20 percentage points. Spending by the top quartile increased too, but by not even half as much, consistent with the different spending needs of high- and low-income households, as well as the much higher levels of savings among high-income families discussed above.

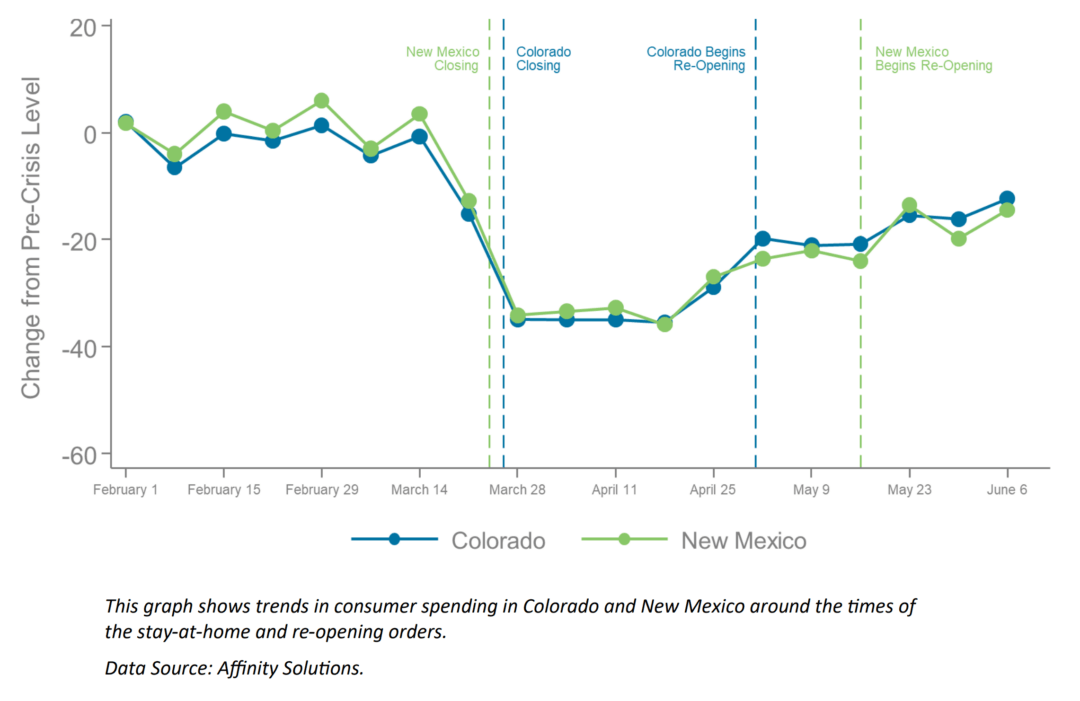

Chetty and his co-authors also examine two other recent government policies to prop up consumer spending and employment: state governments’ declarations that they were reopening their economies and the Paycheck Protection Program, a $670 billion effort to provide loans to small businesses that convert to grants if employees are rehired. The researchers find that both of these efforts have had limited effects because they do not address the underlying cause of the fall-off in consumer spending—the public health concerns that are keeping people home, notwithstanding announcements about reopenings.

The authors offer a case study of Colorado and New Mexico. These two states issued stay-at-home orders within days of one another in late March, and then Colorado partially reopened its economy May 1 while New Mexico didn’t do so until May 16. Despite this difference in reopening dates, there’s no discernible difference in spending between the two during early May. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Different economic reopening dates did not make a difference in consumer spending

Effects of reopening on consumer spending in Colorado and New Mexico, February 2020–June 2020

Similarly, the authors’ analysis of the Paycheck Protection Program find it had negligible effects on employment—total payroll at businesses fell by about 40 percent for both small firms eligible under the program and larger firms that weren’t eligible. Instead, the researchers’ analysis found that PPP loans were most likely to go to industries and the areas that were the least likely to experience job losses during the pandemic.

Professional, scientific, and technical services, for example, received a greater share of loans than did accommodation and food-service businesses. This is consistent with research recently highlighted by Equitable Growth from University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill economist T. William Lester, which showed that small, independent restaurants are suffering particularly acutely during the coronavirus recession, with current programs ill-suited to their needs.

The coronavirus and the economic recession it triggered have caused widespread physical and economic suffering. This latest research clearly illustrates that until the public health crisis is addressed, economic activity will not return to anything close to “normal,” regardless of whether state officials declare their economies reopened. Therefore, government efforts to address the public health crisis must be improved.

In the meantime, policymakers should concentrate their efforts not on stimulus measures for the rich or for businesses, but on supporting the incomes of the tens of millions of workers who have lost their jobs, who are far more likely to have been low-income to begin with and have little savings to draw on. Most importantly, this includes extending the additional $600 in Unemployment Insurance benefits contained in the CARES Act, which are set to expire at the end of July.

This extra $600 is the easiest way to ensure that most workers and their families are able to get close to full wage replacement and continue to support themselves during what is increasingly looking like a prolonged economic recession. Other policies, such as providing stimulus for the rich, re-employment bonuses, or credit to businesses, will do little to reduce economic hardship when it is increasingly clear that economic activity simply will not come back while the threat of contagion continues.