Labor organizations and Unemployment Insurance: A virtuous circle supporting U.S. workers’ voices and reducing disparities in benefits

Overview

In March 2020, communities across the United States realized the gravity of the novel coronavirus pandemic and the deadly reach of COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus. As businesses shut their doors to prevent the transmission of the disease, the joint federal-state Unemployment Insurance program, which funds and administers unemployment benefits, provided important income replacement for people who could no longer report to work. Today, as March’s waves of temporary layoffs turn into permanent job losses, the role of the Unemployment Insurance system in stabilizing the U.S. economy and providing income security to unemployed workers and their families is no less crucial.

Yet although the continuing coronavirus recession makes clear the importance of unemployment benefits, the severe strains on the Unemployment Insurance system illuminate the deep flaws in the program. Inadequate financing for administration continues to cause long delays for workers who apply for unemployment benefits, as well as the denial of benefits for eligible workers. Stingy benefits paid by many states also leave workers relying on a patchwork system of uncertain federal benefits supplements subject to expiration. And the overlapping timing of this economic crisis with the national uprising over anti-Black racism shines a light on widespread racial disparities in access to unemployment benefits.

These increasingly visible failings are now spurring policymakers to better understand problems with the UI system and how they could be addressed through reforms at the state and federal levels. In this issue brief, we bring new findings to bear on the conversation around UI reform. We document the close connections between worker organization and access to unemployment benefits, as well as workplace collective action. Specifically, drawing on two sources of data—an original survey of essential workers fielded in spring 2020 and the 2018 Current Population Survey UI nonfilers supplement—we identify descriptive evidence that:

- Labor organizations facilitate the use of unemployment benefits and, in the process, help close troubling racial and educational gaps in access to Unemployment Insurance.

- Greater access to Unemployment Insurance amid the ongoing coronavirus recession leads workers to feel more comfortable engaging in workplace collective action to demand better safety and health standards.

Together, labor organizations and Unemployment Insurance form a “virtuous circle,” in which greater access supports workplace collective action, including forming labor unions, which, in turn, support greater access to unemployment benefits. These findings suggest three important implications for public policy, which we detail at the end of this issue brief:

- U.S. labor law and Unemployment Insurance policies should complement one another.

- Federal and state governments should support unions and worker organizations in connecting workers with the Unemployment Insurance system.

- Though there are questions about whether a European model, in which unions or worker organizations directly administer unemployment benefits on behalf of the government, would operate effectively in the U.S. context, policymakers should consider it given the strong level of public support for such a model.

Unemployment Insurance: A vital—yet limited—social insurance program

Unemployment Insurance is the main social insurance program designed to support U.S. workers who lose a job through no fault of their own. By providing partial wage replacement to unemployed workers, Unemployment Insurance addresses both the symptoms of macroeconomic contraction (economic hardship at the individual level) and its causes (decreases in spending resulting in layoffs).

Unemployment Insurance is administered through a federal-state partnership, with the federal government setting program standards and providing funding for the administration of benefits, and individual states designing and implementing their own programs. To qualify for unemployment benefits, workers must satisfy both monetary eligibility criteria (typically amassing sufficient earnings over a four-quarter period to demonstrate attachment to the labor force) and nonmonetary eligibility criteria (typically leaving a job involuntarily and not for misconduct, searching for work, and remaining available for new work).

In many ways, Unemployment Insurance is successful. Unemployed workers who receive these benefits experience less poverty, mortality, and home foreclosures than workers who lack access to the program. The receipt of benefits also boosts worker health, facilitates access to credit, and improves the ability of workers to match with better re-employment opportunities when they return to work.1

At the same time, the coronavirus recession exposes a number of serious and longstanding flaws with the UI program. An erosion of UI financing makes it challenging to administer the program well, and many workers have faced difficulty accessing benefits because of cumbersome application procedures, outdated technical infrastructure, and overburdened staff.2 Many states have made unprecedented cuts to unemployment benefits since the Great Recession more than a decade ago, with some states now providing as few as 12 weeks of benefits, down from a customary 26 weeks.3 Significantly, the program’s overall structure has not changed much since its creation in the 1930s. This means the UI system is increasingly poorly matched to the changing nature of work. 4

An especially glaring problem with Unemployment Insurance involves low rates of applications for benefits and the actual take-up of those benefits. Many workers who are eligible to receive benefits do not apply for them in the first place. There are two key points that affect one’s ability to receive UI benefits. The first is the worker’s decision whether to apply. The second is the state’s decision whether the worker is eligible to receive benefits, which ultimately translates to the receipt of unemployment benefits.

In between each of these decision points, there are a variety of administrative hurdles that workers must clear. One is the potential difficulty of completing an application and undergoing recertification each week to demonstrate continued eligibility to receive benefits. Another is the potential difficulty of properly adjudicating eligibility decisions and disbursing benefits on the part of the state.

Through it all, workers must contend not only with state administrators but also the firms where they previously worked, which may attempt to discourage or challenge UI claims.5 Firms fight claims because employers’ UI contributions are linked to the payment of benefits to their previously employed workers, which means a greater number of workers’ claims will raise employers’ payroll tax liabilities.

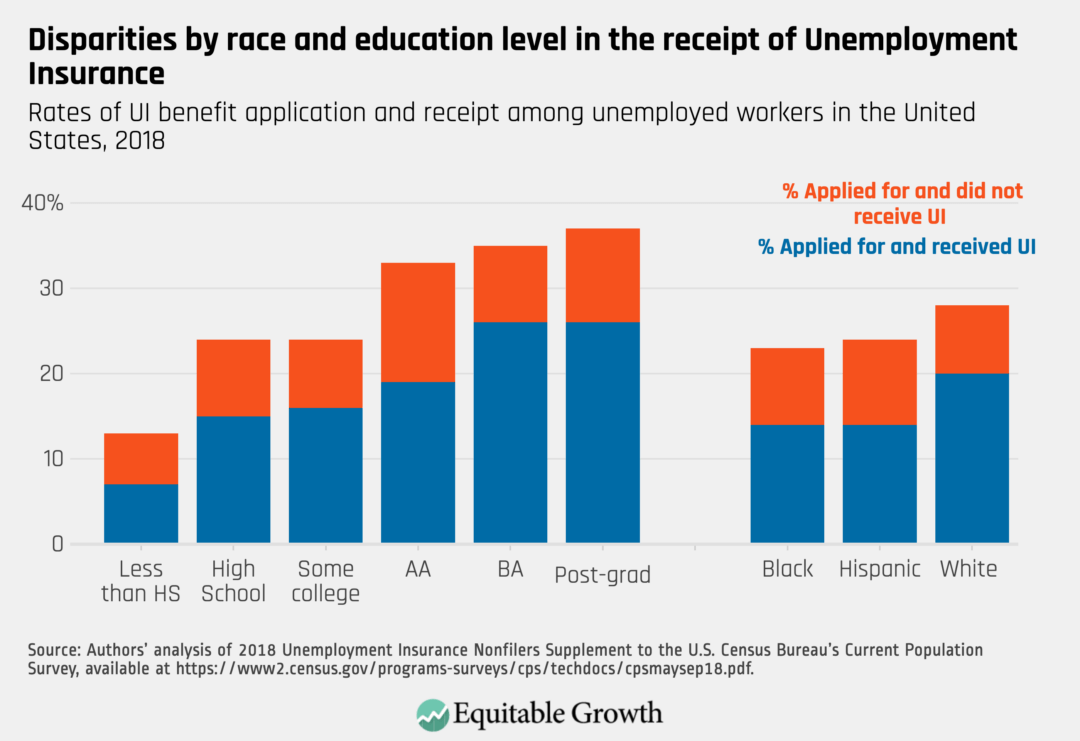

At each administrative hurdle, historically marginalized workers—especially workers of color and workers with lower levels of formal education—face barriers in accessing unemployment benefits. We can see this clearly when examining the UI nonfilers supplement to the Current Population Survey, the best nationally representative data collected on how unemployed workers make decisions about filing for Unemployment Insurance and whether they receive it.

According to the 2018 Current Population Survey UI supplement, 28 percent of White, non-Hispanic unemployed workers applied for benefits, compared to 23 percent of Black unemployed workers and 24 percent of Hispanic unemployed workers. Differences by education were even starker: Just 20 percent of unemployed workers with a high school degree or less applied for benefits, compared to 27 percent of jobless workers with some college education and 35 percent of jobless workers with a 4-year college degree or more.

Data about who actually receives unemployment benefits also show disparities along the lines of race and education. Twenty percent of unemployed White workers received benefits, compared to 14 percent of Black and Hispanic unemployed workers. Across education levels, just 12 percent of jobless workers with a high school degree or less reported receiving benefits, compared to 17 percent of unemployed workers with some college and 26 percent of jobless workers with a college degree or more.

In sum, unemployed workers of color and those with less education are less likely to apply for unemployment benefits and, conditional on application, also are less likely to receive them. More recent, though less detailed, demographic data on access to Unemployment Insurance confirm these disparities have persisted throughout the coronavirus recession, with unemployed Black, Hispanic, and other workers of color remaining substantially less likely to apply for, and receive, Unemployment Insurance.6 (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Because of discrimination in the U.S. labor market, workers of color have lower earnings and thus are less likely to meet monetary eligibility criteria.7 Their employers may be more likely contest their claims, and they are disproportionately clustered in states with onerous application and recertification processes.8 In addition, there are several reasons why workers may fail to apply for unemployment benefits in the first place. They may not be aware of the program. They may not believe themselves to be eligible for the UI program. Or they may see the program as a source of stigma, or they may believe that it is too difficult to apply.9

The disparities in levels of applications for unemployment benefits and levels of receiving those benefits among less-educated workers and workers of colors are concerning because they signal that jobless workers who might most need them are not accessing them. Depressed levels of access to the UI program also dampen the ability of the program to play its role stabilizing the macroeconomy when it is most needed. Yet the lack of access to unemployment benefits does not just threaten the ability of the UI program to support the economy. It also undermines workers’ voices in the workplace, as the following section documents.

Unemployment Insurance and workplace collective action

There is good reason to think that unemployment benefits might affect the possibilities for collective action by workers in their places of employment. If workers are less fearful about the prospects of losing their jobs because of access to generous and timely unemployment benefits, then they might be more likely to engage in workplace actions to raise labor standards and organize unions. Indeed, past research suggests that generous Unemployment Insurance systems in other countries help foster more vibrant labor movements and worker organizing.10

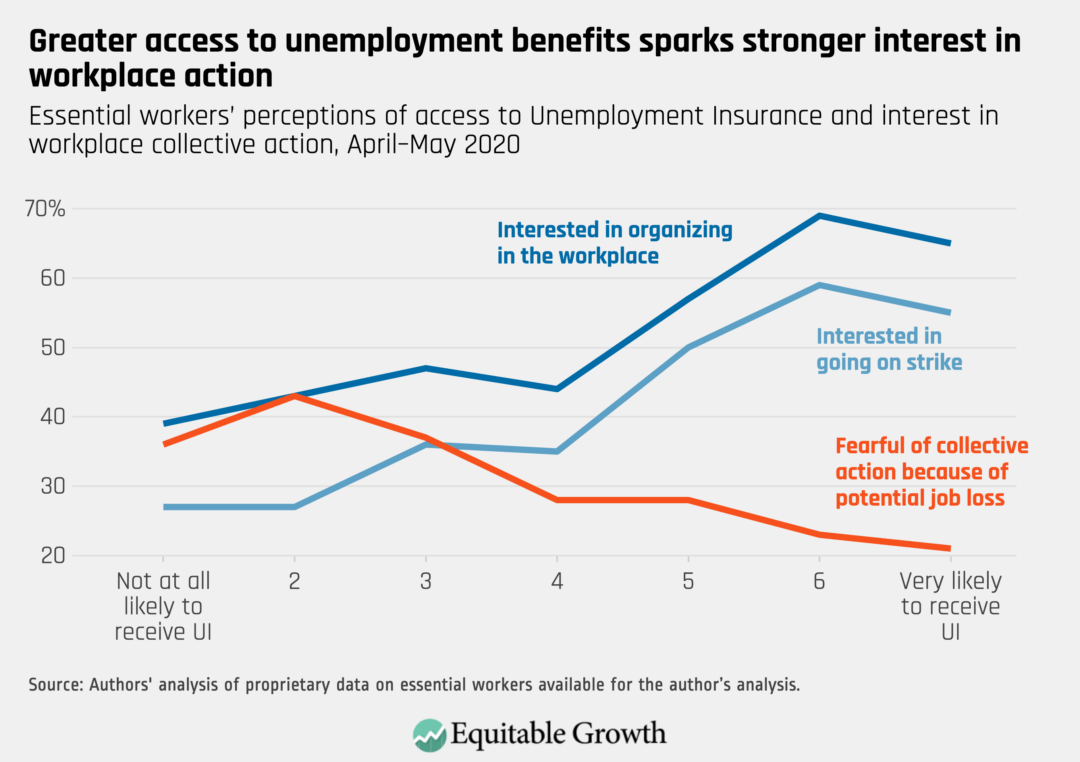

In this section, we draw on an original nationally representative survey of 2,662 essential workers conducted at the early height of the coronavirus recession in late April and early May 2020 to understand the relationship between workers’ perceptions of access to Unemployment Insurance and their interest in workplace collective action.11 The timing of this survey was important because it was fielded at a moment when essential workers faced substantial risks to their health given the spread of COVID-19 and the uneven availability of protective equipment, such as masks or gloves.

The timing of the survey also overlapped with a number of high-profile labor actions at both traditional employers, including large retail chains such as Target and Whole Foods, and gig economy businesses, including Instacart and Amazon.com Inc.12 And the survey coincided with the temporary—and large—expansion of unemployment benefits as part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act enacted by Congress in late March 2020. The new law not only extended eligibility for Unemployment Insurance to workers traditionally excluded from state UI programs, such as self-employed workers, but also added $600 per week to conventional UI payments.

Did the availability of these generous new unemployment benefits and broadened coverage encourage workers to be more comfortable engaging in workplace actions to address health and safety conditions? To answer this question, we can turn to several questions on the survey.

The first item asked respondents how likely they thought they would be to receive unemployment benefits if they had to quit their jobs due to health or safety reasons, on a scale of one to seven, which we use to gauge workers’ perceived access to Unemployment Insurance.13 The second set of items asked how likely workers would be to participate in a range of collective action at their jobs to address health and safety issues related to the coronavirus pandemic, including participating in a strike and joining a worker organization, on a one-to-four scale.14 The final set of survey items asked why workers might be reluctant to engage in collective action at their jobs, including if workers were fearful of losing their jobs.15 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Figure 2 shows that workers who were more confident in their ability to access Unemployment Insurance were more likely to express interest in joining worker organizations and going on strike to address health and safety concerns at their jobs. Workers who were most confident about this access were about twice as likely as those who were least confident about this access to express interest in both forms of collective action.

In addition, workers who were more confident in their access to unemployment benefits were substantially less likely to say that the obstacle to collective action was their fear of losing their jobs. This implies that access to the UI program drives comfort with collective action by reducing the downside risks of losing one’s job. Importantly, all three relationships—interest in joining a union, going on strike, and fear of collective action resulting in losing one’s job—remain virtually unchanged even after adjusting for a range of respondent characteristics.16

The essential workers survey thus suggests that unemployment benefits not only provide an important source of economic security to workers and their families, but also underpin employees’ voices in their workplaces, supporting collective action necessary for securing the resources and protections workers need to keep themselves and their communities healthy amid this pandemic. The protection that Unemployment Insurance affords to workers who might otherwise be fearful of losing their jobs or facing pay cuts is especially important because U.S. employers can and do discipline and fire workers for speaking out about working conditions.

Investigative reporting reveals companies blocking worker attempts at collective action amid the coronavirus recession across numerous industries. They include online giant Amazon.com, food conglomerate Cargill Corp., the ubiquitous fast-food chain McDonald’s Corp., major retailer Target Corp., and the regional sit-down restaurant chain Cheesecake Factory Inc. All of these companies have either barred workers from sharing information about COVID-19 cases in their workplaces or restricted workers from speaking out about poor workplace health and safety standards.17

Given that access to Unemployment Insurance is so important for empowering workers, how can policymakers ensure that all workers—especially historically marginalized workers—have access to the system? We turn next to the role that labor unions play in connecting workers with UI benefits.

Labor organizations and access to Unemployment Insurance

Just as access to unemployment benefits supports workplace collective action and unionization, unions also help workers exercise their legal rights—including applying for and receiving unemployment benefits.18 On an informational level, unions can help workers become aware of the UI program and the process necessary to apply for and continue receiving jobless benefits.19 On a practical level, union staff can help workers to complete their initial claims for unemployment benefits, as well as the ongoing certifications necessary to document continued eligibility for benefits.

By normalizing discussion about using unemployment benefits, unions may additionally help to reduce any stigma surrounding the UI program that might prevent workers from applying—a major impediment to take-up of other U.S. social programs.20 Unions also can protect workers against retaliation from employers seeking to prevent workers from claiming benefits. And lastly, by setting higher standards around wages and work schedules, unions might make it more likely that workers would qualify for unemployment benefits in the first place by meeting both monetary and nonmonetary eligibility criteria.

Indeed, in many ways unions are uniquely well-equipped to connect workers with the UI program. Unions often have close and trusted relationships with workers, including historically vulnerable workers—relationships that can be used to convey information and assistance about the program. Because access to Unemployment Insurance lowers barriers to labor organizing, unions and other labor organizations have a strong incentive to help members access the program. And, perhaps most importantly, labor organizations such as unions and many alt-labor groups are unique because they are designed to pursue democratic accountability. This focus on democratic accountability, both in mission and organizational structure, pushes them to help their members secure important labor market benefits, including Unemployment Insurance.

Indeed, past research indicates that unions historically played an important role in facilitating access to unemployment benefits. Using the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth for 1979–1991, labor economists John Budd at the University of Minnesota and Brian McCall at the University of Michigan document that unionized workers were more likely to receive unemployment benefits.21 The authors found no differences between white-collar workers receiving unemployment benefits depending on whether they were in a union job, but identified large differences among blue-collar workers depending on union coverage. Blue-collar workers laid off from union jobs were about 23 percent more likely than comparable workers to receive Unemployment Insurance. Repeating the same exercise using Current Population Survey data from 1996, Budd and McCall reached nearly identical conclusions.22

In this brief, we extend and update this analysis of union differences in UI access, relying on the 2018 Current Population Survey UI Supplement to understand whether unions can continue to facilitate more workers receiving unemployment benefits even after decades of declines in union membership.

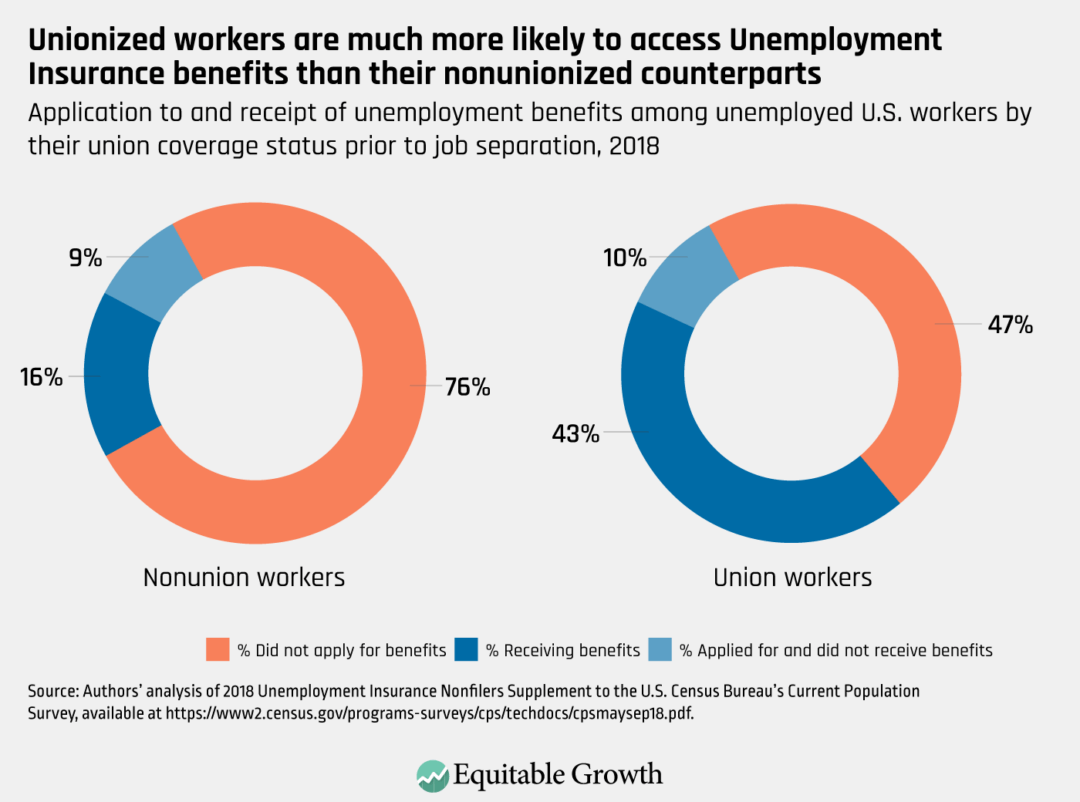

Looking first at overall rates of access to Unemployment Insurance among unemployed workers with recent work histories, we find that workers who had previously been in a union job were substantially more likely to report that they applied for unemployment benefits and received them than were workers who had not been in union jobs.23 (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Figure 3 shows that only 24 percent of nonunion workers reported applying for benefits in 2018, but 53 percent of unionized workers did—more than double the nonunion rate. The difference was even larger when looking at those workers who received unemployment benefits. Just 16 percent of nonunion unemployed workers reported receiving benefits in 2018, compared to 43 percent of unionized jobless workers.

One question is whether the union difference reflects the effect of unions themselves or the characteristics of workers in unionized workplaces. If more highly educated workers are more likely to work in unionized businesses and are also more likely to apply for and receive unemployment benefits, then the union difference might be spurious—reflecting workers’ educational attainment and not unions themselves. Similarly, unionized workers might be more likely to live and work in states with easier-to-access UI programs.

To account for these possibilities, we estimated the union difference in either UI application or receipt while adjusting for a range of worker and job characteristics. We additionally factored into our analysis the states where workers lived to account for the characteristics of underlying UI programs, such as the generosity of benefits or eligibility requirements.24 Importantly, we also factored in the reason workers reported for being unemployed.

With these adjustments, we find that unemployed union workers were about 19 percentage points more likely to apply for Unemployment Insurance and were also about 19 percentage points more likely to receive these benefits. The magnitude of these effects is very similar to those identified in past research, suggesting that unions are continuing to help workers apply for and ultimately receive UI benefits.

Unions facilitate access to unemployment benefits. But can they help close gaps in UI application and receipt among workers of color and those workers with less education? We examine this question next.

Labor organizations and disparities in UI access

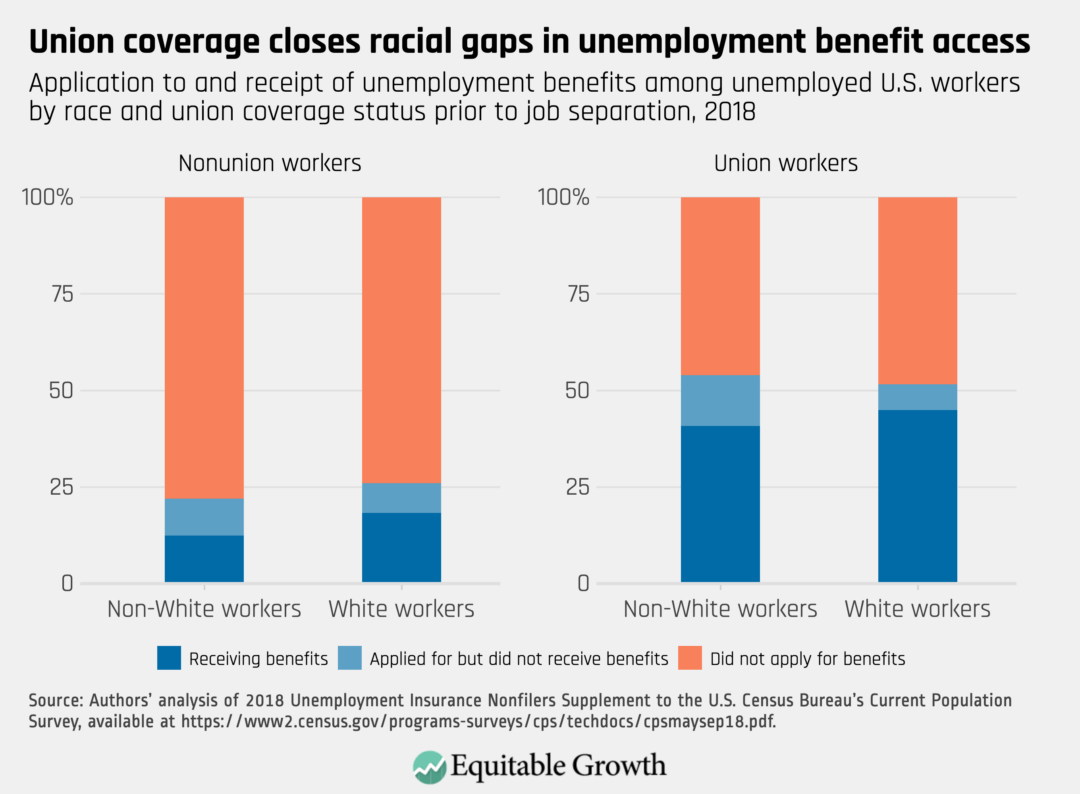

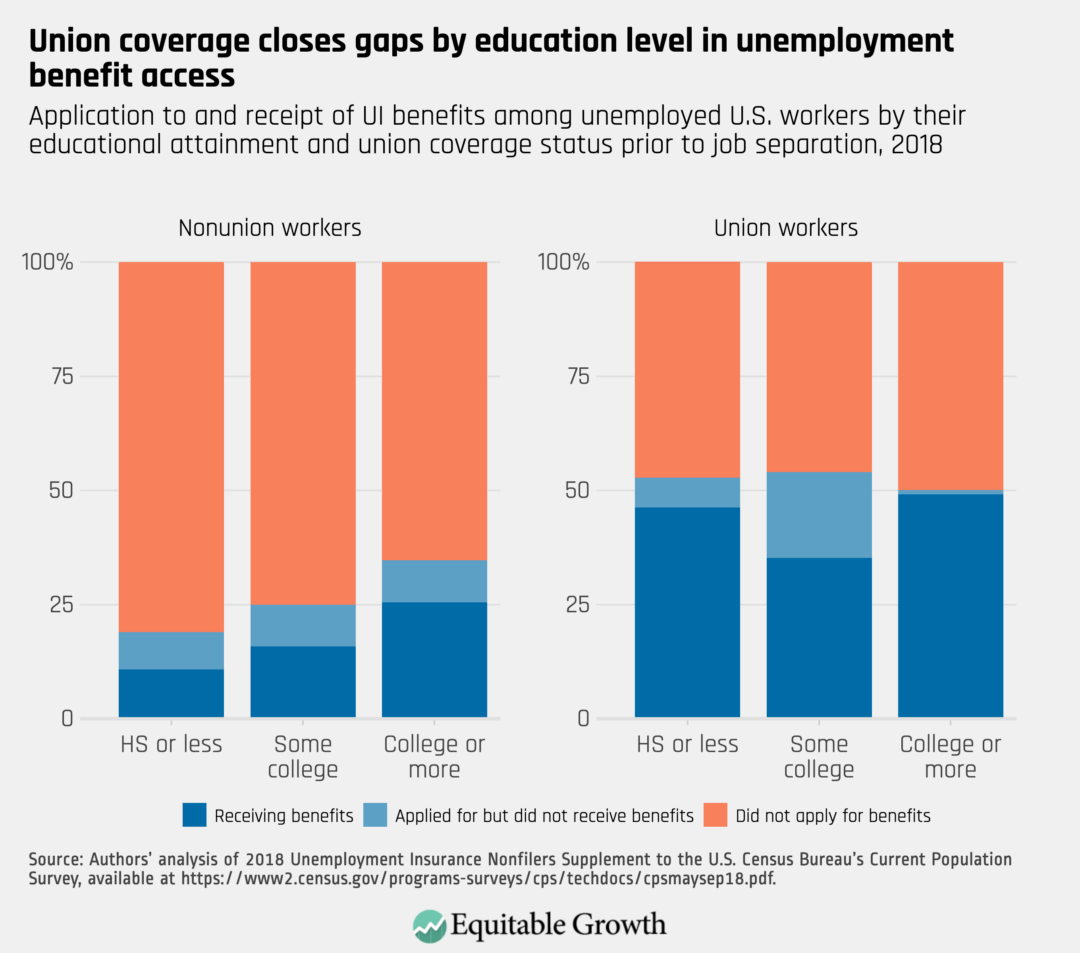

We find that unions can help address the stark inequalities in applying for and receiving unemployment benefits by education and race and ethnicity that we documented earlier. Figures 4 and 5 show rates of UI application and receipt by union coverage and race or education.25 In each case, unionized workers are more likely to apply for and receive benefits, confirming the results in the previous section. But, just as importantly, these gaps in rates of access and receipt are smaller between union workers than for nonunion workers.

Looking first at race, among those workers outside of the labor movement, non-White workers are about 17 percent less likely to apply for and 32 percent less likely to receive unemployment benefits than are White workers. This is a relatively large divide. But among unionized workers, the gap in receiving these benefits by race fell to just 9 percent, and the trend reverses at the point of application, with workers of color being slightly more likely to apply for benefits (though the difference is not statistically significant). (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

For nonunion workers, more educated workers are more likely to apply for and receive unemployment benefits than their less-educated counterparts. This trend does not hold for union workers, indicating that inequalities across formal levels of education are much smaller for union members, compared to nonunion workers. Indeed, these differences are not statistically significant. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

Implications for reforming the Unemployment Insurance system

This issue brief documents how unions play an important role in the U.S. Unemployment Insurance system, helping jobless workers to apply for and receive benefits that they need to support themselves and their families and that boost the U.S. economy during economic downturns. In recent years, unionized workers are about 19 percentage points more likely to apply for and receive benefits than are nonunionized workers, even after accounting for worker, job, and state characteristics. Just as importantly, our results suggest that unions may help to close large gaps in access to and receipt of unemployment benefits—gaps that limit jobless benefits for already marginalized workers.

Too often, policymakers and academics alike separate issues related to Unemployment Insurance and those related to unionization and worker power. When it comes to crafting sound policies for both of these areas, our issue brief implies that policymakers should work across these siloes. There are several concrete measures that policymakers concerned with these issues should consider.

First, policymakers who focus on worker organization should consider the serious shortcomings of the U.S. Unemployment Insurance system. These failings prevent many workers from feeling that they are truly insured against involuntary job losses and have important implications for worker power.26 When workers are more confident that they can claim unemployment benefits, they are more comfortable exercising their voices in their workplaces. In addition to raising benefit access and generosity, one concrete reform that policymakers should thus consider is making Unemployment Insurance more widely available to workers engaged in labor strikes or other forms of collective action on the job.

Second, at a time when policymakers are debating measures to expand access to unemployment benefits, our research suggests that unions ought to be a central part of those reforms. Unions are already connecting workers, especially vulnerable workers, to unemployment benefits and could do even more in a reformed UI system. For instance, policymakers might consider creating federal and state funding for worker organizations—including unions, but also worker centers and other labor groups—to help facilitate even greater access to these benefits. Such funding would formalize the benefit navigation function that unions are already providing to millions of jobless workers and additional resources would permit unions to reach even more workers.27

Finally, there is an active policy conversation about building unions or other worker organizations into the Unemployment Insurance system. Permitting worker organizations to run unemployment insurance funds of their own on behalf of state governments and the federal government—what is known as a Ghent-style UI system—is used successfully in several Northern European countries.28 Still, lower levels of union membership in the United States could pose challenges to successfully implementing such an approach across all states, territories, and the District of Columbia. In addition, a key lesson amid the coronavirus recession is the need to increase the strength of the UI system so that it is more—not less—centralized. And policymakers would need to ensure that worker-led UI funds provide a baseline level of benefits to all eligible workers, regardless of whether they are union members.

On the other hand, many U.S. unions have longstanding experience administering health and benefit funds, and worker-led UI funds could improve access to the Unemployment Insurance system at a time when the infrastructure for administering UI benefits is quite weak. Moreover, as we detail above, unions may have advantages in providing labor market services such as UI benefits alongside other services such as job search and training functions, given their close relationships to both workers and employers. Many American workers say they support this type of change, which is why policymakers should thoughtfully consider it as an option for helping unions to reach more workers interested in labor representation, while also scaling up access to the Unemployment Insurance system.29

End Notes

1. Wayne Vroman, “The Great Recession, Unemployment Insurance and Poverty” (Washington: The Urban Institute, 2010); Daniel Sullivan and Till Von Wachter, “Job displacement and mortality: An analysis using administrative data,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 124 (3) (2009): 1265–1306; Joanne W. Hsu, David A. Matsa, and Brian T. Melzer, “Unemployment insurance as a housing market stabilizer,” American Economic Review 108 (1) (2018): 49–81; Elira Kuka, “Quantifying the benefits of social insurance: Unemployment insurance and health,” Review of Economics and Statistics 102 (3) (2020): 490–505; Joanne W. Hsu, David A. Matsa, and Brian T. Melzer, “Positive externalities of social insurance: Unemployment insurance and consumer credit.” Working Paper No. w20353 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2014); Ammar Farooq, Adriana D. Kugler, and Umberto Muratori, “Do Unemployment Insurance Benefits Improve Match Quality? Evidence from Recent US Recessions.” Working Paper No. w27574 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020).

2. Matthew Haag, “They Filed for Unemployment Last Month. They Haven’t Seen a Dime,” The New York Times, April 17, 2010.

3. George Wentworth, “Closing Doors on the Unemployed” (New York: National Employment Law Project, 2017).

4. Conor McKay, Ethan Pollack, and Alastair Fitzpayne, “Modernizing unemployment insurance for the changing nature of work” (Washington: Aspen Institute/Future of Work Initiative, 2018), available at https://assets.aspeninstitute.org/content/uploads/2018/01/Modernizing-Unemployment-Insurance_Report_Aspen-Future-of-Work.pdf.

5. Alix Gould-Werth, “Workplace experiences and unemployment insurance claims: How personal relationships and the structure of work shape access to public benefits,” Social Service Review 90 (2) (2016): 305–352.

6. William E. Spriggs, “The Two Unemployment Crises and Social Equity.” Testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis, June 18, 2020; Austin Clemens, Raksha Kopparam, and Carmen Sanchez Cumming, “Equitable Growth’s household pulse graphs: September 2–14 edition” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020).

7. Major G. Coleman, “Job skill and black male wage discrimination,” Social Science Quarterly 84 (4) (2003): 892–906; Adam Storer, Daniel Schneider, and Kristen Harknett, “What explains race/ethnic inequality in job quality in the service sector” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2019); Monée Fields-White and others, “Unpacking Inequities in Unemployment Insurance” (Washington: New America, 2020).

8. Michele Evermore, “Unemployment Insurance During COVID-19: The CARES Act and the Role of Unemployment Insurance During the Pandemic.” Testimony before the United States Senate Committee on Finance, June 9, 2020; Ava Kofman and Hannah Fresques, “Black Workers Are More Likely to Be Unemployed but Less Likely to Get Unemployment Benefits” (New York: ProPublica,2020).

9. Janet Currie, “The take up of social benefits.” Working Paper No. w10488 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2004); Gould-Werth, “Workplace experiences and unemployment insurance claims: How personal relationships and the structure of work shape access to public benefits.”

10. Matthew Dimick, “Labor Law, New Governance, and the Ghent System,” North Carolina Law Review 90 (2012): 320–78; Bruce Western, Between Class and Market: Postwar Unionization in the Capitalist Democracies (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997).

11. The survey was conducted by YouGov Blue. For more details on the survey methodology, see Alexander Hertel-Fernandez and others, “Understanding the COVID-19 Workplace: Evidence from a Survey of Essential Workers” (New York: Roosevelt Institute, 2020).

12. Kate Bahn, Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, and Carmen Sanchez-Cumming, “Why workers are engaging in collective action across the United States in response to the coronavirus crisis” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020).

13. Item text: “On a scale of 1-7, how likely do you think you would be to receive unemployment benefits if you quit your job due to safety or health reasons?”

14. Item text: “How likely would you be to join an organization of other workers like you to improve working conditions at your employer?”; “How likely would you be to participate in a strike to improve working conditions at your employer?”

15. Item text: “What are the reasons you would not be very likely to take actions to improve working conditions at your employer?” Response: “Might lose job.”

16. Regressions controlled for gender, age (in five bins), race, education (in four bins), region, union membership, supervisory responsibilities, establishment size, and occupation.

17. Josh Eidelson, “Covid Gag Rules at U.S. Companies Are Putting Everyone at Risk,” Bloomberg Businessweek, August 27, 2020.

18. John W. Budd, “The Effect of Unions on Employee Benefits and Non-Wage Compensation: Monopoly Power, Collective Voice, and Facilitation.” In J. T. Bennett and B. E. Kaufman, eds., What Do Unions Do? A Twenty-Year Perspective (New York: Transaction Publishers, 2007); Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, “American Workers’ Experiences with Power, Information, and Rights at Work: A Roadmap for Reform” (New York: Roosevelt Institute, 2020); David Weil, “Individual Rights and Collective Agents: The Role of Old and New Workplace Institutions in the Regulation of Labor Markets.” In R. B. Freeman, J. Hersch and L. Mishel, eds., Emerging Labor Market Institutions for the Twenty-First Century (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2004).

19. On the importance of information and assistance in applying for government programs, see Amy Finkelstein and Matthew J. Notowidigdo, “Take-Up and Targeting: Experimental Evidence from SNAP,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 134 (3) (2019): 1505–56.

20. On the importance of stigma in benefit use, see Sarah K. Bruch, Myra Marx Ferree, and Joe Soss, “From Policy to Polity: Democracy, Paternalism, and the Incorporation of Disadvantaged Citizens,” American Sociological Review 75 (2) (2010): 205-26; Currie, “The take up of social benefits.”

21. John W. Budd and Brian P. McCall, “The Effect of Unions on the Receipt of Unemployment Insurance Benefits,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 50 (3) (1997): 478–92.

22. John W. Budd and Brian P. McCall, “Unions and Unemployment Insurance Benefits Receipt: Evidence from the Current Population Survey,” Industrial Relations Journal 43 (2) (2004): 339–55.

23. Our measure of unionization includes workers who had been covered by a union contract in their last job and therefore counts both members and nonmembers alike.

24. We controlled for the following individual characteristics: nativity, race and ethnicity (with indicators for Hispanic ethnicity and race in four categories), education (with indicators for high school or less, some college, or college or more), age (with indicators for ages 16–24, 25–35, 36–50, and older than 51), gender, and family income (with indicators for less than $25,000, $25,000–$39,000, $40,000–$74,000, and more than $75,000). We controlled for the major occupational and industry codes of workers’ last jobs, as well as the reason for workers’ unemployment (i.e., job losers, job leavers, temporary job ending, and labor market re-entrants). Lastly, we included state fixed effects to account for state UI systems, among other state-level differences.

25. We are unable to disaggregate the racial/ethnic and educational categories in further detail because of sample size concerns among unionized workers.

26. For examples of a labor law reform agenda, see Sharon Block and Benjamin Sachs, “Clean Slate for Worker Power: Building a Just Economy and Democracy” (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Law School Labor and Worklife Program, 2020); Sharon Block and Benjamin Sachs, “Worker Power and Voice in the Pandemic Response” (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Law School Labor and Worklife Program, n.d.).

27. David Madland and Malkie Wall, “American Ghent: Designing Programs to Strengthen Unions and Improve Government Services” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2019).

28. Dimick, “Labor Law, New Governance, and the Ghent System”; Madland and Wall, “American Ghent: Designing Programs to Strengthen Unions and Improve Government Services.”

29. Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, William Kimball, and Thomas Kochan, “How U.S. Workers Think About Workplace Democracy: The Structure of Individual Worker Preferences for Labor Representation.” Working Paper (Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2019).