It’s no surprise that the Kansas tax cut experiment failed to create jobs

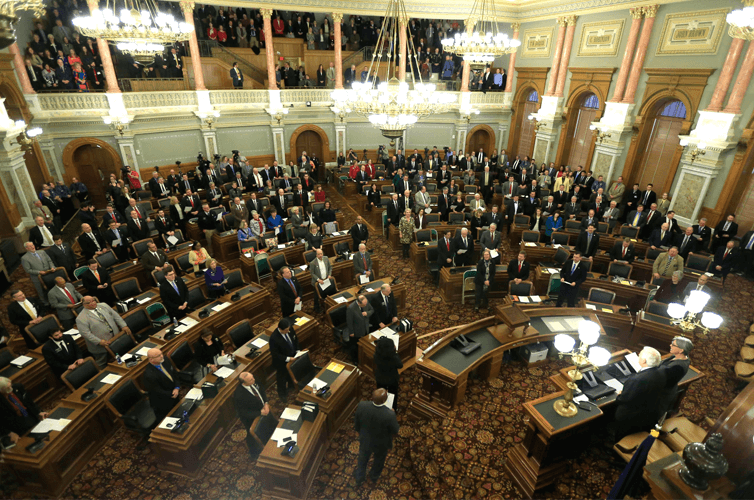

A supermajority of Kansas legislators last week voted to roll back Gov. Sam Brownback’s (R) signature tax cuts, overriding his veto. The tax cuts, enacted in two stages in 2012 and 2013, caused a recurring series of budget crises and cutbacks that angered voters and in turn spurred a bipartisan coalition of legislators to reverse several of their most harmful elements.

Proponents of the tax cuts argued that they would unleash economic growth and job creation. Yet as numerous subsequent analyses demonstrate, the promised economic growth did not materialize. Tax revenues fell sharply. Job growth and output growth disappointed. Population growth, whether as a cause or consequence of the economic growth, failed to materialize. Finally, last week, state legislators recognized the experiment’s failure and reversed course.

Understanding the reasons that the Kansas tax cut experiment failed to create jobs is particularly important given that the outline for tax reform rolled out by the Trump administration in April shares many features with the Kansas model. U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin says the administration’s plan “is all about jobs, jobs, jobs,” much as Gov. Brownback did in Kansas five years ago. In fact, subsequent reporting suggests that the Trump administration’s tax plan was rolled out in an incomplete state because the president read an op-ed in The New York Times co-authored by some of the same advocates who provided advice to Brownback on his tax plan.

The failure of the Kansas tax cut experiment to create jobs has little to do with Kansas, however, and everything to do with the fact that the underlying economics of tax reform—as envisioned by Gov. Brownback and President Donald Trump—isn’t a good path to jobs. To understand this point, it’s worth considering in turn the two primary types of taxes that were cut under the Kansas plan and in the Trump administration’s outline: taxes on labor income and taxes on business profits.

Claims of supply-side growth from labor income tax cuts rely on the idea that people will be more willing to work when their after-tax wages are higher. This theory posits that labor income tax cuts result in growth because people who could increase their earnings choose not to because tax rates are too high, but it does not take much to see why cutting tax rates for middle- and higher-income families does not create jobs through this mechanism. Middle- and higher-income families already have jobs, even if they are not the jobs they necessarily want.

Claims of supply-side growth from tax cuts on business profits rely on the idea that those cuts will increase the level of investment and that, in turn, will increase productivity. Under this theory, a tax cut on business profits could increase employment by spurring investment, increasing wages, and attracting people into the labor force who are not willing to take a job at current wage rates. For this theory to work, however, it would need to be the case that cutting statutory business tax rates would meaningfully reduce the effective tax rate on an incremental investment such that the tax cut causes businesses to increase investment. Second, it would need to be the case that the reduced tax rate causes businesses to increase investment in a way that increases the wages they would be willing to pay to people who currently choose not to work because wages are too low. Third, it would need to be the case that this increase in wages would be large enough to spur people who currently choose not to work to enter the labor force and seek jobs. And finally, the deficits resulting from the tax cuts would need to be small enough that they increase businesses’ cost of capital by less than the reduction resulting from the lower tax rate, as a higher cost of capital would cause businesses to reduce investment rather than increase it.

These conditions are highly unlikely to hold in practice. Businesses already pay relatively little tax on the incremental return from investments in tangible capital due to tax benefits such as accelerated depreciation and interest deductibility, and they often pay no tax—or even receive a tax subsidy—on marginal investments in intangible capital. Moreover, reducing the statutory tax rate on business income actually increases the effective tax rate on debt-financed investment, which is a common source of financing for investments in tangible capital because businesses deduct interest payments from taxable income.

The so-called crowd out effect from government deficits on debt markets was not a significant concern in Kansas because of balanced-budget requirements and the small size of the state relative to U.S. debt markets, but tax cuts such as those proposed by the Trump administration would cause a substantial increase in federal borrowing and likely lead to meaningful crowd out. Finally, even if there were an impact on wages despite the questionable empirical validity of the links between business tax rates and take-home pay, it would be tiny relative to the other costs and benefits of work and therefore would likely generate little impact on employment.

Thus, given the underlying economic logic, it should come as no surprise that the Kansas tax cut experiment failed to deliver job growth. Similar reforms at the national level would be no different.

If federal policymakers are looking for a supply-side tax reform that would create jobs, then they could expand the Earned Income Tax Credit, or EITC, for low-income families, particularly workers without dependent children. The EITC provides a substantial boost in take-home pay for low-income workers with children and encourages workers who are out of the labor force to seek jobs. A substantial academic literature finds that the EITC boosts labor supply, creating jobs. Notably, these labor supply effects result from a boost in wages far larger than anything on offer from even the most optimistic assessment of the impact of business tax cuts. The EITC boosts pre-tax wages for families with one, two, and three or more children by 34 percent, 40 percent, and 45 percent, respectively. Even an unprecedentedly large expansion of the EITC could be accomplished for a fraction of the cost of President Trump’s high-income and business tax cuts.