Implications of Reifschneider, Wascher, and Wilcox’s Estimates on the Immediate Need for Lots of Expansionary Policy: Tuesday Focus

As Reifschneider et al. politely put it:

Endogeneity of [long-run potential aggregate] supply with respect to [short-run] demand [shortfalls] provides a strong motivation for a vigorous policy response to a weakening in aggregate demand…

And, boy, do they find a very strong endogeneity of long-run potential aggregate supply–roughly three times as strong as the numbers I have been using for finger exercises over the past two years. And, boy, does the arithmetic then tell us that this then calls for a “vigorous” policy response…

Let me give the mike to Ryan McCarthy to explain the issues:

Ryan McCarthy: Growing pains:

At the IMF’s research conference… three Fed economists examined America’s economic wounds. A paper, by Dave Reifschneider, William Wascher, and David Wilcox, studied whether the economy has been permanently damaged by the effects of the financial crisis… “hysteresis”, a concept coined in 1986 by Larry Summers and Oliver Blanchard, in a seminal work on the European labor market. The Fed authors find that America’s potential GDP is about “7 percent below the trajectory it appeared to be on prior to 2007”. Before the crisis, America’s economy had the potential to grow at about 2.6% per year, the authors find; since the crisis, America’s potential growth rate has been just 1.3%. You can blame this decrease in productive capacity, the authors write, on things like lower productivity and persistently high unemployment…

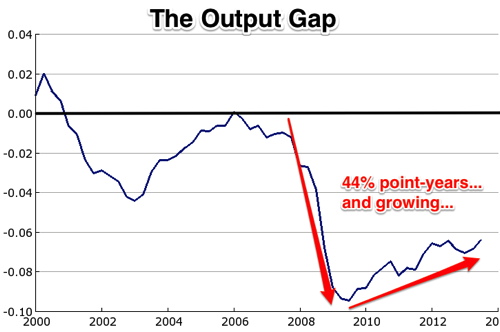

Since the start of the crisis we have had 44% point-years of “output gap”–of shortfall of actual production from potential, from what the economy could produce at full employment if supply balanced demand, and without upward pressure on inflation. And now come Reifschneider et al. to tell us that such a prolonged and deep depression generates an apparently-permanent one-time reduction in the growth path of potential GDP by 6.5%.

This is, in the language of DeLong and Summers’s 2012 “Fiscal Policy in a Depressed Economy” a value of η = 0.15.

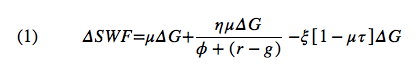

DeLong and Summers (2012) had a simple framework for evaluating whether expansionary fiscal policy passed a benefit-cost test at the zero lower bound in which central banks could not or did not offset the aggregate-demand effects of fiscal policy and so the net-of-monetary-offset Keynesian multiplier μ > 0. (We argued that away from the zero lower bound the net-of-monetary-offset Keynesian multiplier μ = 0, and so only at the ZLB was there a case for fiscal policy as an activist stabilization policy tool.

In a framework with a net-of-monetary-offset Keynesian multiplier μ, a hysteresis effect-of-depression-on-potential-output parameter η, a speed-of-hysteresis-decay parameter φ, a marginal tax share of GDP τ, a trend growth rate g, a real interest rate/discount factor r, and a cost-of-raising-extra-tax-revenue parameter ξ, the net benefits of expansionary fiscal policy would be given by:

with:

- μ ΔG being the current-period boost to production;

- η μ ΔG/(φ+(r-g)) being the present value of the future boost to aggregate supply from higher potential output resulting from reduced hysteresis due to a faster recovery;

- [1-μ τ] ΔG being the extra government debt incurred that needed to be financed; and

- ξ[1-μ τ] ΔG being the present value of the deadweight loss that must be financed.

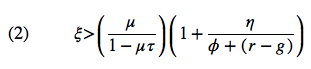

(1) implies that expansionary fiscal policy is a very good idea as long as the deadweight-loss cost ξ of raising an extra dollar of tax revenue satisfies:

With a marginal tax share τ = 1/3, an interest rate r that certainly looks no bigger than the growth rate g, and a Keynesian multiplier μ = 2, this equation becomes:

With Reifschneider et al.‘s η = 0.15, then assuming a hysteresis-decay parameter φ = 0.05, expansionary fiscal policy is a bad idea only if ξ > 24: only if it costs more than $24 in reduced welfare to raise $1 of tax revenue.

Until we get away from the ZLB, expansionary fiscal policy to boost the economy really is a no-brainer.

And the alternative hypothesis that the decline in the growth rate of supply-side potential output was going to happen anyway, and is not a knock-on effect of the demand shortfall. As Ryan McCarthy concludes:

Is it realistic to suggest that the economy’s capacity to expand has halved in five years? Population growth hasn’t ceased. Americans aren’t any less hardworking than they were five years ago, and their skills haven’t declined precipitously.

As Reifschneider et al. conclude:

Endogeneity of supply with respect to demand provides a strong motivation for a vigorous policy response to a weakening in aggregate demand…

And as Janet Yellen wrote back in 1988: in a framework like this, “Okun’s Law [calculations] understate the benefits of running a high-pressure economy…”–and also understate the costs of accepting a low-pressure one.

1089 words