How Much There Is There in Attempts to Ascribe Any Significant Component of Our Current Economic Distress to “Policy Uncertainty”?: Wednesday Focus

I have always thought that the idea that there is a lot of “there” there is, at best, unproven–and given the energy that has been devoted to trying to prove it, that the failure to connect the links is strong evidence that there is not much there there at all,

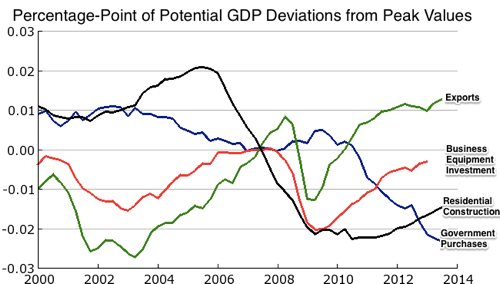

Thus one of the analytical points made about the past six years I have not understood is a focus on “policy uncertainty” a la Baker, Bloom, and Davis as a factor holding back the U.S. economy. Residential construction is 1.5%-points of GDP below its level the last time the U.S. was at full employment, government purchases its 2.5%-points below its peak level, business equipment investment is nearly at its peak level, and exports are 1.5%-points of GDP above their level at the last peak. Add these up and we get a 2.5%-point of GDP drag. Apply today’s standard multiplier and add on a little bit for depressed household wealth and we have explained the shortfall in real GDP relative to potential.

Where is the space for policy uncertainty to matter? You can say that depressed residential construction is a result of uncertainty about future housing finance policy, but it is a reach to do so rather than simply to say that housing finance is wedged along a number of dimensions, and that is not what people mean by “policy uncertainty” anyway. The stock market tells us that whatever uncertainty there is is not leading owners of capital to want to sell off their shares at a discount. So I genuinely do not see why this is supposed to be a major contributing cause to our current macroeconomic distress:

Or how, indeed, the Obama administration’s acceding to the latest policy demand of the week from the Republican House caucus is supposed to do much to reduce whatever component of this measure is not just the Washington echo-chamber but actually affects people’s perceptions of risk and opportunity.

But I could always be wrong…

Thus I am interested to note that lunch at the Berkeley Women’s Faculty Club yesterday I learned just how strongly David Romer more than agrees with me–and that he had in fact said so at some length on November 8, at the IMF’s Jacques Polak conference:

David Romer: Comments on “Will the U.S. and Europe Avoid a Lost Decade? Lessons from Japan’s Post Crisis

Experience”:

…So it is even more plausible than it is for Japan that aggregate demand problems have been central to what has been going on in Europe and the U.S. [since 2007].

The last sleight of hand is something that features in the paper. I do not think that Takeo mentioned it at all in the discussion. They do eventually acknowledge that their story is not complete. And then in the U.S. case they then go immediately to a discussion of “policy uncertainty” and the work of Baker, Bloom, and Davis. So I want to spend my last few minutes on that.

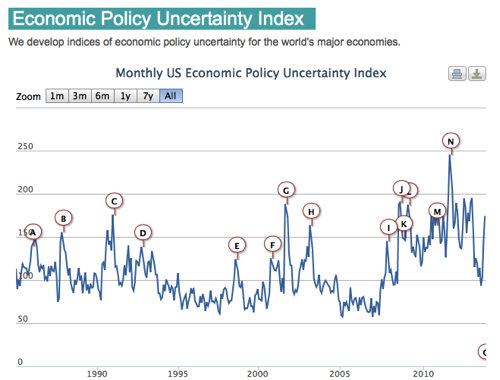

Comment 1 is: Why single out “policy uncertainty” rather than all the forces I have mentioned that are clearly holding back demand? The Baker, Bloom, and Davis work has to be taken with an enormous grain of salt. This quick resort to stories about policy uncertainty is something that I think we should avoid. I get the appeal of the Baker, Bloom, and Davis work. It is an important subject. They are serious people. They are working really hard at it. But in the end I think that it just does not lead us all that far.

There are two really big problems:

The first is: Baker, Bloom, and Davis do not even find a clear correlation between their measure of “policy uncertainty” and subsequent economic activity. Once you control for stock-market uncertainty–or in an earlier draft they did the experiment of controlling for confidence–with either of those controls there is just not much of a remaining correlation between their index of policy uncertainty and what happened subsequently to the economy.

Second, correlation is not causation. There are really compelling reasons to think that some of that remaining correlation is coming from nonpolicy factors adversely affecting the economy being correlated with their index, thus overstating the causal impact of “policy uncertainty”. I have three reasons: let me focus on what I think is the most important. Think about what causes “policy uncertainty”. One obvious thing is big adverse shocks hitting the economy. If the economy is sailing along smoothly, there are going to be disagreements about whether we should raise or lower the federal funds rate a little bit, whether we should tighten or loosen fiscal policy a little bit. There will be the usual disagreements about long-run fiscal policy. But we are not going to have a disagreement about whether we should have an $800 billion TARP stimulus or should we be bailing out the banking system? Because the economy is doing fine, nobody is going to be advocating measures like that.

In other words, there is an incredibly obvious mechanism by which big adverse nonpolicy shocks hitting the economy are going to cause “policy uncertainty”. That is the main one. I have two others: I will do them incredibly briefly in the interest of time:

One is that one component of their index is uncertainty about inflation over the coming year. It is supposed to be an index of monetary policy uncertainty. The horizon is so short that I think that what it is picking up is supply shocks.

There is also the issue that in the past few years there has been an artificial increase in a narrative measure of policy uncertainty from policymakers deciding to focus on that.

Let me wrap up because the organizers want me to. I have spent most of my time focusing on saying: “don’t focus entirely the issues that Takeo and Anil are drawing your attention to. The conventional accounts stressing the importance of weak aggregate demand and both policy and private-sector actions restraining aggregate demand deserve to stay at the center of our attention. But Takeo and Anil do raise some very important and interesting issues. And what they have to say about them is incredibly insightful. I learned a lot from the paper. Thank you.

David Romer: Slides:

…#4: From Acknowledging that Their Story Is Incomplete to Discussing Policy Uncertainty

Why single out policy uncertainty rather than other forces that are clearly holding back demand? More importantly:

Baker, Bloom, and Davis do not find even a clear correlation between their policy uncertainty index and subsequent economic activity.

There are compelling reasons to think that Baker, Bloom, and Davis’s index is correlated with nonpolicy factors adversely affecting the economy, and thus that what correlation there is overstates the effect of policy uncertainty:

One cause of uncertainty about policy is big nonpolicy shocks.

Disagreement about inflation over the coming year is unlikely to be driven mainly by uncertainty about monetary policy.

In recent years, some policymakers have deliberately emphasized the issue of uncertainty about policy, artificially raising the index.

…

Conclusion

Please do not give all your attention to the issues that Hoshi and Kashyap focus on–keep some of it on more conventional theories stressing the importance of weak aggregate demand.

But: What they have to say about the issues they focus on is insightful and valuable.

1328 words