More women in the United States are working past retirement age

It’s not uncommon for working women and men to scale back their hours to part-time as they grow older. But a growing number of women are bucking this trend, working past the traditional retirement age. According to a new paper by Harvard University economists Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz, the growth in women’s increased labor force participation beyond their 50s and into their 60s and 70s is overwhelmingly driven by those working full-time.

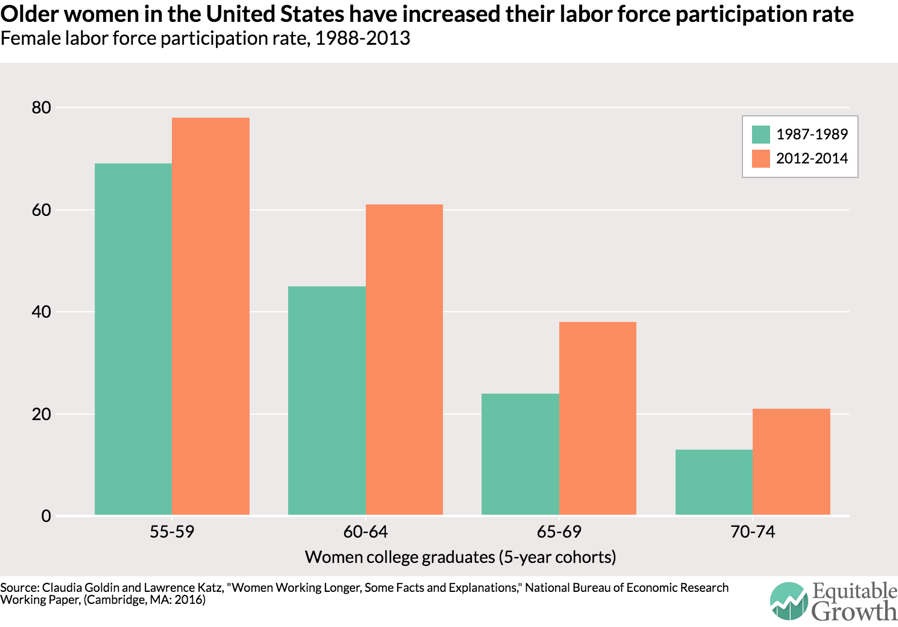

So why are more women working longer? Part of the explanation has to do with women’s increased labor force participation overall. The women who today are in their 60s and 70s are much more likely to have worked throughout their life compared to those who were at those same ages 10 years or 20 years ago. Education also plays a role: College-educated women (as well as college-educated men) are much more likely to work full time into their 60s and 70s compared to less-educated Americans. The number of older women in the workforce with a bachelor’s degree also is rising. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

At first glance, it may seem that anemic savings have something to do with this new labor force trend. About 60 percent of all U.S. households have no savings in an Individual Retirment Account or defined-savings retirement plan such as a 401(k) account. A recent Federal Reserve report on economic well-being finds that 26 percent of those surveyed claimed their retirement plan is to “keep working as long as possible.”

But Goldin and Katz find that financial insecurity isn’t the whole story. The increase in later-life employment is happening among women who are better educated and healthier, which tend to go hand-in-hand, and therefore are more likely to be in white-collar occupations that are relatively well-paid. What seems to matter is whether women enjoy their jobs. As Goldin and Katz say, “As jobs become more enjoyable and less onerous and as various positions become part of one’s identity, women work longer.”

What your spouse does also matters. Women are more likely to remain working if their partner is working, too, compared to other married women. Considering that a larger number of couples are delaying retirement than they were two decades ago, this also plays into this trend.

The same can be said for women’s early work history. Women who reach a certain level of career advancement early on are much more likely to still be employed past their 50s, regardless of how much they earned. In addition, while those who have children are less likely to be working full time (or at all) between the ages of 25 and 44, kids don’t seem to affect their return to the workforce later on, although it does have a major impact on women’s wages throughout their lifetime.

This finding is important considering that Goldin and Katz find that more recent cohorts of 40-year-old women are less likely to be working between the ages of 25 and 44 compared to older generations. A college-educated woman born between 1964 and 1968, for example, was less likely to be working at age 40 compared to her counterpart born between 1944 and 1948, which the authors attribute to a lack of family friendly policies such as paid leave (a sentiment other researchers have echoed). But considering the increase in education and more young women joining the labor force in recent decades, researchers suggest that older women’s employment will only grow in the coming decades, despite the dip in participation when raising children.

All of these factors play a quantifiable, predictive role in driving older women’s labor force participation. But Goldin and Katz note that the number of college-educated women in their 60s still working is higher than these factors would anticipate, meaning that there is an unknown factor keeping them in the labor force. The same can be said for younger women as well, who will “likely retire later than one would have predicted based on their educational attainment and lifecycle participation rates.”

Regardless of why, what’s clear is that this is not an isolated phenomenon: Women are likely to continue working past “traditional” retirement age for years to come. This could have important implications for the size and productivity of the U.S. workforce in the future.