Context may be everything when it comes to the Phillips curve

It’s been a few months since we last checked in on the Phillips curve, or the relationship between unemployment and inflation. The curve has been the center of many debates over the course of monetary policy, most recently due to the Federal Reserve’s decision to raise interest rates last month. Fed chair Janet Yellen cited Phillips curve-style thinking in her speech about inflation back in September.

Now, with U.S. wage growth seemingly accelerating over the end of 2015, it’s worth thinking about how the relationship between the strength of the labor market and inflation is holding up.

In a policy brief for the Peterson Institute of International Economics, Olivier Blanchard—senior fellow at the Institute and former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund—looks at the vitality of the Phillips curve in the United States. While he finds that the curve still has a pulse, the unemployment/inflation relationship is decidedly different from the curve’s previous incarnations.

First, the slope of the Phillips curve has declined. This means that inflation will increase less for a given decrease in the unemployment rate. At the same time, inflation expectations have become, in economics-speak, incredibly “well-anchored.” Investors believe quite strongly that U.S. inflation will stay around 2 percent and that the Fed will fight to maintain their (now explicit) target.

This anchoring means the curve resembles its 1960s form where changes in the unemployment rate affect the level of inflation, as opposed to its “accelerationist” form where changes in the unemployment rate affect the change in the inflation rate. To put this finding in the terms that University of Michigan economist Justin Wolfers used this past fall, it means we should be more focused on the level of wage growth than its trend at the moment.

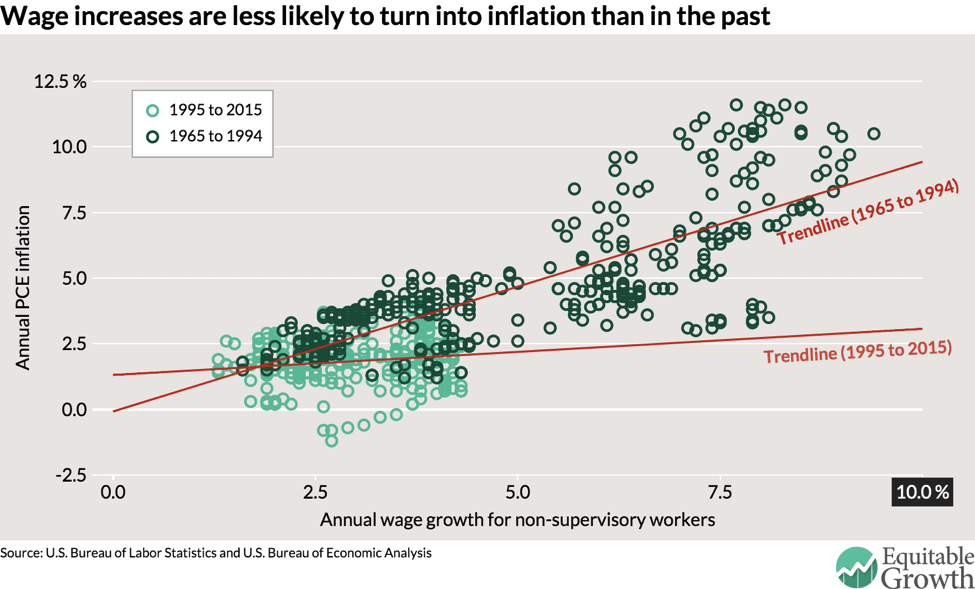

Wage growth, of course, is one of the transmission mechanisms that links lower unemployment to higher inflation. But how much of wage growth gets translated into inflation? Research by Federal Reserve economists Ekaterina V. Peneva and Jeremy B. Rudd finds that wage growth actually doesn’t pass through that much to inflation anymore. This change is easy to see in the following graph (inspired by similar graphs from John Jay College economist J.W. Mason):

The accelerationist Phillips curve relied upon a relatively strong pass-through between wage growth and inflation. But increasing wages don’t have to go entirely toward boosting the inflation rate—higher wage growth might also result in a higher share of income going to labor. J.W. Mason makes this point quite well in another piece on the Phillips curve, or rather the varieties of the curve. Whether the increasing wage growth will go more toward inflation or a higher labor share of income, however, isn’t obvious from a theoretical perspective. In fact, the context of the increasing wage growth seems to make quite a bit of difference.

The accelerationist Phillips curve relied upon a relatively strong pass-through between wage growth and inflation. But increasing wages don’t have to go entirely toward boosting the inflation rate—higher wage growth might also result in a higher share of income going to labor. J.W. Mason makes this point quite well in another piece on the Phillips curve, or rather the varieties of the curve. Whether the increasing wage growth will go more toward inflation or a higher labor share of income, however, isn’t obvious from a theoretical perspective. In fact, the context of the increasing wage growth seems to make quite a bit of difference.

Given the declining share of income going to labor and the high share of income going to profits, perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that wage increases aren’t filtering on to accelerating inflation. The economic situation has changed quite a bit. Stronger wage growth today may do more to increase the labor share of income than spark inflation. And as Mason points out, wage growth that exceeds inflation and productivity growth would result in pushing income more toward wage earners.

Given the times, accelerating wage growth seems unlikely to spark accelerating inflation anytime soon. But if we give it more time, it may help reduce one form of inequality.

Nick Bunker is a Policy Analyst at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth.