Combating market power through a graduated U.S. corporate income tax

Editor’s note: This version has been updated from the original publication on April 15, 2024. The update corrects a prior underestimate of the revenue potential from graduated corporate tax rates resulting from the treatment of tax credits.

This issue brief has been excerpted with minor modifications from a more extensive treatment of these issues in “Capital Taxation and Market Power,” to be published in the forthcoming Spring 2024 issue of Tax Law Review, Issue 77, Number 2.

Overview

Rising market power in the United States and around the world calls for changes to our nation’s international corporate taxation system. The importance of market power today suggests that corporate tax policy should distinguish between normal returns to capital and above-normal returns to capital, the latter of which is a telling indicator of corporations’ market power. This distinction has important consequences for the efficiency and equity of capital taxation.

Market power, alongside long-understood tax administration criteria, strengthens an already-strong case for entity-level taxation. The corporate tax has the potential to distinguish companies based on the magnitude of their reported profits—the larger the company’s taxable income, the more likely that a large share of their corporate tax payments are above-normal returns. The implementation of a graduated corporate tax rate system, presented in this issue brief, has the potential to act as a constant nudge, tilting the playing field in favor of more competitive markets.

Data indicate that the U.S. corporate tax base is very concentrated. In 2019, about 350 companies (out of about 500,000 filers with positive tax liability) account for nearly 70 percent of the corporate tax base. Even among these top companies, total profits are skewed toward the largest companies. Analysis within my working paper, to be published in the Spring 2024 issues of Tax Law Review, suggests that the revenue gains from a graduated rate structure could be substantial, while affecting less than one-half of 1 percent of corporations.

Any proposal to raise corporate income taxes on the largest, most profitable companies will invariably spark questions about global profit shifting, and, indeed, international tax reform has an important role to play in enabling consideration of a graduated U.S. corporate tax system. The largest multinational companies often pay particularly low effective tax rates, due to features of U.S. international tax law that facilitate and incentivize their ability to shift taxable income toward low-tax jurisdictions. To tax these large companies, international tax reforms are needed to make the corporate tax base less tax-elastic.

In this regard, recent advances in international tax cooperation are an encouraging development. In 2021, more than 135 countries representing about 95 percent of the world economy reached a political agreement to levy minimum taxes on multinational companies, and recently, major countries have moved to implement that agreement. The agreement also includes a feature—the undertaxed profits rule—that will encourage adoption by other jurisdictions in the years ahead.

This type of international tax cooperation is crucial for resolving longstanding global collective action problems that have often resulted in a shift of the tax burden away from capital and toward labor or consumption, and, importantly for the topic of this issue brief, paves the way for an anti-monopoly corporate tax in the United States.

Defining market power

Economists often distinguish between two types of firms when considering how to define market power. “Perfectly” competitive firms earn no “economic profit,” or above-normal (excess) returns, but they do earn enough “accounting profit” to pay the normal returns to capital and labor. The free entry and exit of firms in marketplaces assure that, over time, these perfectly competitive firms earn just the amount required to cover normal returns but no more than that. Perfectly competitive firms do not have any control over the prices they face in the marketplace; they are “price-takers.”

In contrast, “imperfectly” competitive firms face downward-sloping demand curves for their output, meaning they have some control over the prices they charge in the marketplace. Imperfectly competitive firms may, in some cases, earn profits above the amount required to cover normal returns to labor and capital, generating economic profits (or excess returns). Firms may accumulate market power due to high barriers to entry into marketplaces, collusion with would-be competitors, or simply the normal economic actions of dominant firms.

In this issue brief and in my working paper, I use the term “market power” to capture situations where firms operate under conditions of imperfect competition, recognizing that there is a wide spectrum of possible outcomes, and market power becomes more policy-relevant when deviations from the perfectly competitive outcome are larger.

Market power and corporate taxation

In recent decades, and especially since 1990, the U.S. economy has experienced growing market concentration, alongside the increased market power of dominant companies. This trend of increasing market power has been sustained and substantial, and it has occurred across a broad swath of U.S. industries. These trends have important implications for the U.S. economy, affecting the bargaining power of firms relative to workers, inequality, consumer welfare, the efficiency of capital allocation, and the broader functioning of markets.

Increasing market power also has important implications for tax policy. Longstanding tax analyses that treat capital taxes as falling on the “normal” return to capital have efficiency implications that are very different from those that hold if capital taxes instead fall on profits above the normal return to capital. The incidence of capital taxes also depends on whether they fall on normal or excess returns. The optimal rate of capital taxation depends crucially on such efficiency and incidence considerations.

The ideal form of capital taxation also depends on these distinctions. Alongside administrative rationale, market power considerations strengthen the argument for the corporate tax as an important tool for achieving capital taxation goals. Further, market power considerations buttress the case for a graduated system of corporate tax rates.

The large role of market power reinforces the already-powerful case for tackling international tax competition and countering international tax avoidance. While international tax reform entails balancing the competing goals of tax base protection with the competitiveness concerns of domestic multinational companies, recent improvements in international tax cooperation make that trade-off less stark. Further, the policy relevance of such competitiveness concerns is impacted by the presence of market power.

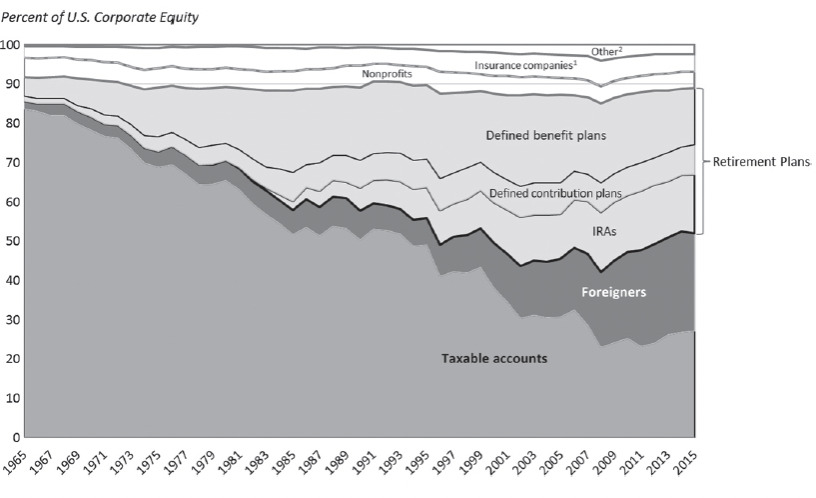

The importance of market power strengthens the argument for taxing capital income at the entity level, rather than the individual level, though there are already important reasons to favor taxation at the entity level. First, entity-level taxation is simply more comprehensive. About 70 percent of all U.S. equity income is completely untaxed by the U.S. government at the individual level. Why? Because this income is either held by untaxable entities, such as nonprofit endowments, or in untaxed accounts, including retirement accounts, pensions, and college savings accounts, or in foreign hands whose governments may or may not tax that income. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Ownership of U.S. corporate stock, including both direct and indirect holdings, 1965 to 2015

Unless many popular tax preferences are reconsidered, much of the capital income tax base is unreachable if one is limited to the individual layer of taxation. Further, the entity level of taxation is the only way to reach most foreign investors in U.S. equity markets. These investors also benefit from the features of the U.S. economy that generate U.S. equity income, so the entity layer of tax is one way to ensure that foreign investors contribute to financing the relevant government services.

Second, even for those accounts that are taxable by the U.S. government, the taxpayer has substantial discretion over when, and indeed if, capital taxation occurs. While corporate dividends may trigger immediate taxation, capital gains are only taxed at realization, so taxpayers can defer taxation (allowing funds to grow free of tax) indefinitely. Further, if assets are held until death, they qualify for a “step-up” in basis, so that capital gains escape taxation entirely. Any shares donated to charity will also escape taxation.

Finally, entity-level taxation can also serve as an important backstop for the individual income tax, preventing those individuals with discretion from channeling funds into corporations, retaining earnings, and obtaining lower tax rates as a consequence. The more the corporate rate falls below the top individual rate (or pass-through rate), the more the corporate form acts as a tax shelter.

Beyond these rationales, the presence of significant and rising market power makes the argument for the corporate tax stronger. The corporate tax has long played an important role as a regulatory device. Governments can use the tax system to influence the behavior of corporate actors. Corporate investment is spurred through rounds of bonus depreciation, research and development is incentivized through the R&D tax credit, and other activities such as clean energy, low-income housing, and the development of orphan drugs (treating rare diseases) are encouraged through general business credits.

In a similar manner, the more that the corporate tax base overlaps with a tax base that is solely excess profits, the greater the efficiency justification for the corporate tax. Taxing excess profits generates government revenue, allowing society as a whole to share in the fruits of the exercise of market power (or the fruits of luck or risk-taking), without deterring investment or economic activity. Indeed, if the corporate tax fell onlyon excess profits, one could justify (on efficiency grounds) much higher tax rates than today’s 21 percent rate, especially if one could address international mobility issues.

Prior to the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, there was a modest graduated rate in the corporate tax rate structure, but most of the corporate tax was paid by corporations that were at the top marginal rate of 35 percent, which applied at the $10 million income threshold. A slightly lower 34 percent marginal rate applying for income between $75,000 and $10 million, and lower marginal rates of 25 percent and 15 percent applied for income below $75,000 and $50,000, respectively.

Since 2018, the corporate tax has been levied as a flat 21 percent rate. There is a good argument for a flat rate of tax. Unlike the individual income tax, a graduated rate in the corporate arena need not improve progressivity. For instance, we do not know that wealthier people are more likely to own shares in the most profitable corporations (as opposed to less profitable ones), relative to those lower in the income distribution. Thus, a graduated rate structure is an indirect (and potentially ineffective) way to achieve progressivity goals.

Yet the larger the company’s taxable income, the more likely that a large share of their corporate tax payments are above-normal returns. In my working paper, I detail why the U.S. tax code provides favorable or neutral treatment to many types of investment (subsidizing debt-financed investment and allowing expensing or favorable depreciation regimes in many instances), such that there is a large overlap between the corporate tax base and a tax base on rents. Thus, companies that comprise a large share of the corporate tax base are also likely to be those earning rents. Further, the Fortune or Forbes lists of the most profitable companies show that many of them benefit from large market shares, and many are in fields—such as technology, pharmaceuticals, or finance—where intangible capital (the normal return to which is untaxed) is an important source of value.

Since taxing above-normal returns is both more efficient and particularly likely to burden shareholders, a higher tax rate may be justified. By contrast, for less profitable companies, more of the corporate tax burden may fall on investment or labor.

Beyond these favorable incidence effects, a graduated corporate tax can also discourage size itself, as well as the accumulation of economic power, which has negative consequences for the broader economy. A graduated rate does not distinguish among the causes of size—which could result from economies of scale, luck or first-mover advantages, risk-taking, access to some key resource, or other factors—but it does tilt the tax playing field against large-profit companies relative to small-profit companies, improving the competitive environment in a clear and transparent manner.

While a somewhat-higher tax rate will not prevent companies from becoming large, which may be warranted or even desirable in many instances, it will act as a marginal disincentive for mergers, acquisitions, and agglomeration itself.

European Union antitrust authorities have been active, and U.S. antitrust efforts appear to be on the rise, but it is difficult for antitrust law to address many prevalent instances of market power. Antitrust processes require due deliberation, focus on different criteria for market power, can be slow, and often act as a blunt on/off switch, rather than as a continuous policy lever. While company mergers have been blocked on occasion, and there have been instances of fines or regulation, antitrust remedies are generally infrequent.

Tax policy reform cannot replace antitrust policy (nor should it), but it can be a useful complement that provides a continuous policy signal in favor of a more competitive marketplace. A higher tax on more profitable companies, for example, would provide a direct and transparent tax preference for companies operating in a relatively competitive environment, compared to those that are more insulated from competition. And given the distribution of corporate profits and tax payments in the United States, even a small hike in the rate at the top could have large revenue consequences.

Enacting a graduated global U.S. corporate tax system

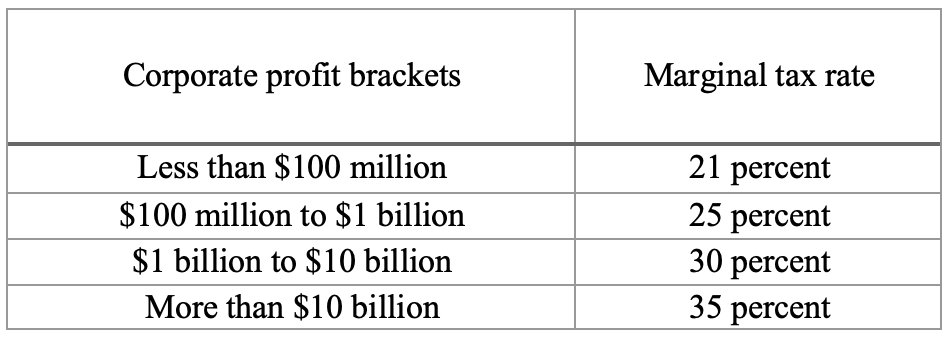

One way to enact a graduated global U.S. corporate tax system could keep the corporate rate at its present level of 21 percent for smaller-profit companies, while raising the corporate tax rate for those companies with higher profits. Marginal rates would be calculated as they are presently under the individual income tax system, so that the increased rate would only apply to income above the thresholds in question. Table 1 illustrates one possible graduated corporate tax rate schedule.

Table 1

Example of graduated global U.S. corporate tax rate schedule

In Table 1, corporate taxpayers with $2 billion in income, for example, would pay 21 percent on their first $100 million in income, 25 percent on $900 million of their income, and 30 percent on $1 billion of their income, for a total tax bill of $546 million and an average tax rate of 27.3 percent. Importantly, a graduated rate of corporate taxation was, until recently, a feature of the corporate tax, so this sort of rate structure is not unprecedented. And, under current law, there are many provisions that are more favorable for small companies, as well as some base protection measures that only affect large companies.

Examples of the former include special expensing rules under Section 179, under which approximately $1 million of investment can be deducted, and the favorable treatment is phased out at higher investment levels (above about $2.9 million). Examples of the latter include 163(j) interest limits, which affect only those taxpayers with more than $27 million in receipts in 2022, and the base-erosion anti-abuse tax, or BEAT for short, which affects those with average annual gross receipts of $500 million or more. Indeed, the BEAT exists to counter avoidance opportunities that are far more likely to occur among large companies.

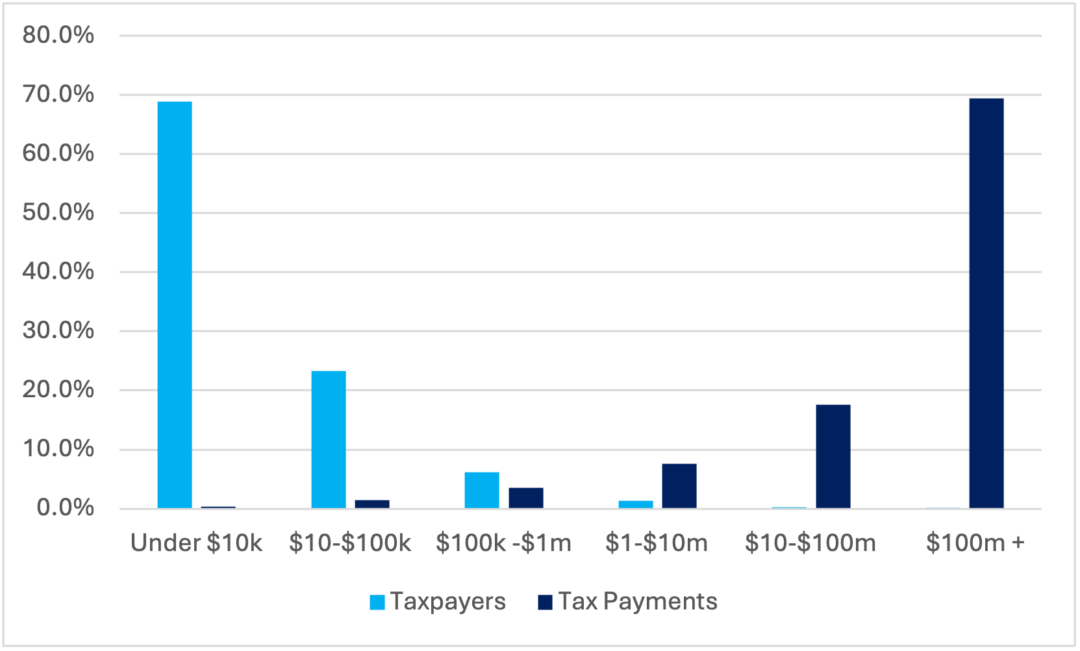

While publicly available IRS data do not allow an investigation of the exact breakdowns of Table 1, one can examine proximate statistics for 2019, the most recent year not affected by the COVID-19 pandemic (though 2020 data lead to similar inferences). (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Distribution of corporate taxpayers and corporate tax payments, 2019

It is readily apparent that most corporations would be untouched by the tax-bracket reform that is illustrated in Table 1. Of the approximately 500,000 corporate tax returns filed in 2019 with positive tax liability, fewer than 2,000 of them had tax payments of more than $10 million (and thus taxable income nearing $50 million). Indeed, about 99.7 percent of corporate taxpayers fall below those thresholds, and thus even more would be excluded from the reform suggested above.

But most of the tax base would be affected by this reform, since 87 percent of the tax payments are made by corporations above the $10 million tax payment threshold, and 69 percent of all corporate tax is paid by companies with tax payments of more than $100 million (and thus with taxable income nearing $500 million). The average company with more than $100 million in tax payments has $3.2 billion in taxable income.

Consider the revenue effects of this reform in 2019 under two (restrictive) assumptions: There is no behavioral response, and each corporation has a situation that is the average of those in their IRS segment. In that event, tax burdens would only increase for fewer than 4 out of 1,000 corporations with positive tax liability. For those with tax payments between $10 million and $50 million, about one-third of the average company’s taxable income (which averages $154 million) would be subject to an additional 4 percent tax; this group of taxpayers would pay $2.5 billion in additional tax. There are 272 taxpayers with tax payments between $50 million and $100 million, who have an average taxable income of $593 million, so about 83 percent of their income would have an additional 4 percent tax rate applied, generating about $5 billion in tax revenue.

For the 353 companies with tax payments of more than $100 million at present, who have an average taxable income of $3.2 billion, about 69 percent of their income would be taxed at 30 percent, and another 28 percent of their income would be taxed at 25 percent. This group would generate about $82 billion in additional tax revenue.

Across these three groups, tax revenues would increase by about $90 billion in 2019, an increase of 35 percent relative to the baseline. This revenue increase is an underestimate in one respect, since assuming everyone in the top bracket is an “average” company removes any additional revenue associated with the 35 percent bracket for those companies with more than $10 billion in profits.

Data from the Fortune 500 list covering the year 2019 suggest that there are about 13 U.S. companies with more than $15 billion in worldwide profits, suggesting they might be above the $10 billion threshold in U.S. profits. Together, these companies generate about $273 billion in profit above the $10 billion threshold. An additional 5 percent tax on that base would generate $14 billion in additional revenue. Approximately one-third to one-half of U.S. corporate profits are foreign profits, so this suggests perhaps about $7 billion to $9 billion in additional U.S. tax, bringing the total to about $98 billion.

These calculations do not account for behavioral response, but one would expect behavioral response along at least three margins. First, if companies face higher tax burdens, they may do less real activity. Given the target population of companies, this is not a big concern, since these companies have large excess profits, and the additional tax is unlikely to fall on the normal return to capital, so it would be relatively nondistortionary.

Second, and more significant, large companies have other ways to respond to higher tax burdens. For instance, they may seek to shift profits toward lower-tax destinations. This would be true even if size thresholds were set based on global income, if the tax base were determined by U.S. reported income. This issue is the most important hurdle to adopting this proposal, and it will be addressed in detail below.

Third, larger companies may split into smaller companies (or do fewer mergers and acquisitions) in order to avoid the higher rates of tax felt by larger companies. If a split were a mere formality, such that ownership and control of the company remained as before, that would circumvent the higher tax burdens for large companies. But the law should ensure that companies would be consolidated for tax purposes if they were not truly separate, and prior law (when the corporate rate structure was graduated) had provisions to address this issue.

With a tight definition of commonality, companies would only be able to separate if they were truly willing to give up the benefits of internalization that result from their combination. Such internalization benefits can be significant. For instance, internalization resolves principal-agent problems, helping to align the profit-maximizing incentives within the group. Internalization allows economies of scale (cost reductions due to greater production scale), economies of scope (cost reductions due to producing a larger number of complementary goods), and synergies associated with cooperative product or service development. When companies break up, they lose many of these advantages.

The hypothetical tax schedule in Table 1 above attempts to balance two considerations. First, scale economies may be beneficial, generating cost savings that benefit consumers, resources that fund innovation, and the capacity to absorb risk. One wouldn’t want to eliminate the possibility of large companies and the attendant advantages of scale.

There also are disadvantages associated with market domination. Concentration of economic power may generate serious negative consequences: depressing wages or employment, systematically lowering the labor share of income, impeding healthy market competition, harming consumer welfare, and corrupting public policy processes. Given these factors, it would be useful to have a public policy tool that counters excessive agglomeration of economic power.

While antitrust law also has an important role to play, the objective of antitrust law can be usefully complemented by a tax code that, at minimum, does not incentivize market concentration, and instead works to promote market competition. The tax code can act as an ever-present nudge in this area, as in so many others, by incrementally changing marginal incentives.

Indeed, the tax code is a statement of values. It encourages things such as clean energy and research by offering them low tax burdens. In this case, market power can be discouraged by levying a somewhat higher tax on those firms most likely to exercise it. This has the salutary effect of allowing society to benefit from those activities that generate above-normal profits, providing an efficient source of finance for fiscal priorities.

At present, the tax code often tilts the playing field in the other direction. Large, profitable multinational companies pay lower rates than smaller domestic companies, often by a substantial margin. In part, this is because multinational companies can avail themselves of opportunities to shift profit offshore, toward jurisdictions with rock-bottom tax rates. These low tax rates advantage large multinational companies relative to their smaller, less profitable peers, turbocharging market concentration.

Further, the causality can go the other way too, as market power fuels tax avoidance. Sophisticated multinational tax avoidance techniques often entail sizable fixed costs, and large profits provide the resources to invest in this expertise. Large companies also invest more in political activity, which can bear large fruits in terms of more favorable tax or regulatory environments. In turn, successful political activity provides policy advantages that fuel concentration.

Implications for international tax reform

The most important objection to taxing large, profitable companies at higher rates in a graduated U.S. corporate tax system is that such companies are particularly adept at shifting income offshore. Therefore, any higher tax rates for the most profitable companies should be accompanied by associated measures that combat international profit shifting.

There are different approaches to tackle profit shifting, but a central aim is to reduce the elasticity of the corporate tax base. Some have suggested full worldwide consolidation, which would require resident firms to pay tax on their global income alongside their domestic income; foreign tax credits would prevent double taxation. This would end the incentive to shift income offshore, although it would put pressure on the definition of residence, so accompanying reforms would need to reduce the elective nature of tax residence by using a management and control criterion and by employing measures to counter corporate inversions. A bill introduced by Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) in the current U.S. Congress takes a similar approach.

One daunting concern with such reforms is that they would hamper the international competitiveness of U.S.-headquartered multinational companies in global markets if foreign income were taxed more heavily than that of their competitors. While this form of competitiveness is a concern, it is less of a concern for those companies that wield substantial market power.

Further, it is also useful to note that the competitiveness of the United States as a place for U.S. multinational companies to undertake economic activity and book profits would be improved. Unlike current law, there would be no tax advantage associated with operating in lower-tax countries, so U.S.-based companies would face no tax distortions in their location decisions regarding where to deploy investments or hire workers.

A more modest reform would simply narrow the existing tax preference favoring foreign income over domestic income. Under current law, the so-called GILTI provision, which stands for “global intangible low tax income,” exempts the first 10 percent return on foreign tangible assets from U.S. tax, and income above that threshold is taxed with a 50 percent deduction relative to domestic income. This provides a large incentive to earn income offshore.

In President Joe Biden’s budgets for fiscal years 2022, 2024, and 2025, the administration proposed eliminating the tax-free return on foreign tangible assets, reducing the deduction for foreign income to 25 percent, and calculating the tax burden on foreign income on a country-by-country basis. Together, these changes would have substantially reduced the incentive to shift profit offshore, lowering the elasticity of the tax base.

In November 2021, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a reform that would move in this direction, applying the GILTI tax on foreign income on a country-by-country basis, lowering the deduction for low-taxed foreign income, and reducing the tax-free return on foreign tangible assets to 5 percent. The U.S. Senate did not pass a similar reform, but instead legislated a corporate alternative minimum tax; this reform will slightly raise the tax burden on foreign income for some multinational companies.

The country-by-country feature of GILTI reforms is important. It further reduces the incentive to earn income in low-tax jurisdictions offshore, since the resulting U.S. tax cannot be offset with tax credits from higher-tax locations.

The GILTI provision operates as a deduction from the normal corporate rate; thus, whatever GILTI design is adopted, it can accommodate higher corporate tax rates (such as those envisioned in the prior section) with proportionate changes in the tax rate that would apply to low-taxed income abroad. Yet the higher the U.S. rate on foreign income relative to the lightest possible treatment of foreign competitors, the more corporations will fear negative competitiveness impacts. Still, it is important to bear in mind that the higher corporate tax rates envisioned in the prior section are triggered by the exceptionally high corporate profits earned by dominant corporations; this should alleviate competitiveness concerns.

Since competitiveness concerns also hold in many countries abroad, this provides a strong argument for international tax cooperation. Left to their own devices, governments often behave as players in a noncooperative game, lowering their tax rate to attract tax base and activity from other countries. Since all countries face similar incentives, tax rates are too low relative to what would be chosen if countries could coordinate.

Luckily, countries cancoordinate, although such coordination is never easy. Still, in 2021, more than 135 jurisdictions accounting for about 95 percent of the world economy agreed to transformative reforms in international tax rules, including a global country-by-county minimum tax of 15 percent. This OECD/G20/Inclusive Framework agreement responds to the “race to the bottom” dynamic in international taxation by raising the bottom, from 0 percent (the approximate tax rate currently levied by some important low-tax jurisdictions) to 15 percent.

Further, the agreement is strengthened by an undertaxed profits rule, or UTPR, which allows adopting countries to top-up tax burdens for companies operating in their markets that are headquartered in nonadopting countries. Such an enforcement mechanism should encourage widespread adoption once a few major economies adopt. Otherwise, companies based in nonadopting countries will still face top-up taxes when they operate in adopting countries—the resulting revenue will just accrue to adopting country governments instead of their home governments.

In December 2022, the European Union unanimously moved forward to implement this country-by-country minimum tax by issuing a Council Directive. In addition, many other countries, including South Korea, Japan, Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom, are also implementing this minimum tax. Hopefully, the United States will soon follow suit.

Based on current implementation plans, OECD researchers have concluded that 90 percent of the multinational companies that are in the scope of the agreement will be covered by its provisions. Of course, this agreement is not perfect. Some forms of tax competition will persist, as countries may offer subsidies or refundable tax credits in place of low tax rates. That said, such measures are more difficult for countries to adopt, as they entail direct budgetary costs, not just foregone revenue. Thus, the constraint on tax competition provided by this agreement is a real one, and it is an important step forward.

In the end, the elasticity of the corporate tax base is a choice. And there are multiple options for reducing the elasticity of the corporate tax base. In the near term, the most practical way forward is to build on the momentum created by the international agreement. International adoption of the OECD/G20/Inclusive Framework agreement will help limit tax competition pressures and reduce profit-shifting incentives.

Foreign adoption of these reforms also supports U.S. international tax reforms that strengthen the GILTI provision, reducing the current tax preference that favors foreign income relative to U.S. income. First, foreign adoption of minimum taxes reduces any competitiveness concerns associated with a stronger GILTI provision, which could otherwise create sizable gaps between U.S. treatment of foreign income and rules abroad.

Second, foreign adoption of the undertaxed profits rule causes U.S. multinational companies to face top-up taxes abroad in adopting countries. Thus, these companies would still face 15 percent tax burdens on their foreign income, but the revenue would go to foreign governments instead of the U.S. government, giving the U.S. government a strong incentive to adopt conforming GILTI reforms.

Further, without adoption of aligned reforms, U.S. multinational companies would risk facing several overlapping minimum tax regimes. Current U.S. law includes the GILTI provision and a Base Erosion and Anti-abuse Tax, or BEAT. Foreign governments will also levy UTPR taxes. In addition, there is the new corporate alternate minimum tax, or CAMT. (The CAMT was part of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. It taxes companies with more than $1 billion in book income at a rate of 15 percent, but it contains special features to avoid clawing back existing investment incentives, R&D incentives, or general business credits. It does not include a country-by-country minimum tax on foreign income.)

With reform of the U.S. international tax rules, as suggested by recent Biden administration proposals, these taxes could conceivably be consolidated, as U.S. companies would no longer pay UTPR taxes abroad, and there would be far less need for the CAMT (especially for multinational companies) or the BEAT.

Other ways to combat market power through the tax code

There are additional ways to improve existing U.S. tax laws to better address market power concerns. For instance, the design of the foreign-derived intangible income, or FDII, deduction is perverse, since it provides a tax break for above-normal returns to some income, relative to normal returns. Under the FDII, companies receive a deduction of 37.5 percent (scheduled to fall to 21.9 percent in 2026) on their income above a 10 percent return on qualified business asset investment if that income is derived from exports. This provision should be repealed. It serves no economic purpose to favor excess profits, and it is an indirect (at best) way to incentivize the development of intangible property in the United States, which would be better targeted by measures that focus more narrowly on research and development.

Another area where tax policy might be reconsidered is that of tax-free reorganizations. Global mergers have surged in recent years, reaching $5 trillion in value in 2021. Mergers can spur market concentration, and while they may generate efficiencies, many mergers fail to do so. Under U.S. tax law, some mergers can be structured to be tax free, when the acquiring firm exchanges some of its stock for target-firm stock; tax is then deferred until the underlying asset is later sold. While there are justifications for such favorable tax treatment, there are also counterarguments, and rising market power provides a strong rationale for reconsidering this tax preference.

Ideally, tax provisions would instead provide lessfavorable treatment to very-high-profit large companies. Under the proposed international reforms and the new CAMT, minimum tax regimes would only apply to large companies, although the thresholds vary. As this issue brief and my more comprehensive working paper argue, that focus on large companies makes good economic sense, as the corporate tax is more likely to serve both efficiency and fairness goals when levied on above-normal returns to capital, and above-normal returns are more likely for companies with high profits.

Compliance costs and tax administration concerns

Administrative complexity provides another reason to focus such provisions on large companies. Large companies have more tax-avoidance opportunities, both due to their international reach, which allows them to exploit variations in tax treatment across jurisdictions, and due to their scale, which helps them afford the fixed costs associated with setting up tax-avoidance structures. The large scale of these companies also helps them comply with complicated new tax provisions, including the minimum taxes described here. While such provisions can be dauntingly complex, the largest companies have the resources required to handle complexity.

Administering graduated corporate tax brackets, as envisioned above, would be straightforward, as applying tax brackets is a simple part of compliance and enforcement. Yet because higher rates would put additional pressure on international profit-shifting incentives, improving international tax rules—and providing the IRS with sufficient resources to administer such rules—are especially important.

Conclusion

Market power is an important force in both the U.S. economy and the world, and a wealth of evidence indicates that market power has become increasingly important in the past few decades. While the scale economies and network effects that are associated with market power generate efficiencies, they also generate policy concerns, through possible detrimental effects on income inequality, labor bargaining power, consumer welfare, and market dynamism.

The importance of market power suggests rethinking common corporate tax policy design concepts. Most important, tax policy should distinguish the normal return to capital from the above-normal return to capital. This distinction has important consequences for the efficiency and equity of capital taxation.

Market power, alongside long-understood tax administration criteria, strengthens an already-strong case for entity-level taxation. The corporate tax has the potential to distinguish companies based on the magnitude of their reported profits: The larger the company’s taxable income, the more likely that a large share of their corporate tax payments are above-normal returns. A graduated corporate tax rate system has the potential to act as a constant nudge, tilting the playing field in favor of more competitive markets.

International tax reform has an important role to play in enabling consideration of such reforms by strengthening governments’ ability to tax the largest multinational companies and making the corporate tax base less tax elastic. Recent advances in international tax cooperation are encouraging, due to the coordinated implementation of minimum taxes on multinational company income. In the years ahead, this agreement can be further improved to allow jurisdictions more tax policy autonomy in addressing both market power and fiscal needs.

—Kimberly Clausing is the Eric M. Zolt Professor of tax law and policy at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Law. She also is a nonresident senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and an NBER research associate.