Closing the billionaire borrowing loophole would strengthen the progressivity of the U.S. tax code

Overview

The vast majority of Americans are concerned that some wealthy people don’t pay their “fair share” of federal taxes. They’re right to be bothered: Loopholes in the U.S. tax code allow some billionaires to pay taxes equal to only 1 percent of the increases in their wealth, which tax textbooks across the country consider “income.”

How is this possible? The low effective tax rate arises in part because U.S. billionaires with large stock portfolios and other appreciated assets can borrow money using their considerable financial assets as collateral and then pay little to no taxes on the cash they use to finance their lifestyles. Some of the wealthiest people in the United States take advantage of this loophole, including Larry Ellison and Elon Musk. Without borrowing, they would have to sell more of their appreciated assets, “realizing” these gains and thus triggering income taxes.

Indeed, Americans with more than $100 million of wealth were recently estimated to hold $8.5 trillion in unrealized capital gains. According to that analysis, these 64,000 households hold as many unrealized gains as does 84 percent of the population, or 110 million households. Closing this billionaire borrowing loophole could raise more than $100 billion over 10 years in a highly progressive and reasonably efficient way.

These are among the findings in our new paper, “No More Tax-Free Lunch for Billionaires: Closing the Borrowing Loophole,” in which we suggest a simple way to close the loophole (and from which this piece is adapted). We propose that the borrowing of those billionaires and centi-millionaires be taxed as realizing income. This new revenue is not only sorely needed from the top 0.05 percent of households, but is fairly owed by them under the progressive principles of our federal tax system.

What’s more, there is an important upcoming window to close this gaping tax loophole. Some of the federal budget-busting provisions in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 will expire in 2025. This would be a good time for federal policymakers to act to restore some fiscal discipline by fixing this part of the U.S. tax code.

This issue brief will quickly detail how taxes levied on U.S. households with net assets of more than $100 million would close this loophole, what the timeframe for levying the tax on borrowed income would be, and how compliance with this change in the federal tax code could be enforced. We will then briefly summarize the economic benefits of enacting this kind of tax reform and demonstrate why possible legal and fiscal arguments against this proposed reform are off the mark.

The design features of our proposed tax on billionaires’ borrowed income are workable ways to address these possible challenges. As policymakers in the Biden administration and the U.S. Congress confront the serious federal budget challenges ahead—after decades of high wealth inequality in the United States—our paper presents a new option to raise revenue fairly and efficiently.

How to close the billionaire borrowing loophole

Let’s begin with some basic illustrative numbers to show how the tax would work. Suppose, for simplicity’s sake, that a billionaire holds all his wealth in the shares of a single Big Tech company. Let’s also suppose that the billionaire originally paid $1 billion for his earliest-purchased stock, but those shares are now worth $10 billion. In other words, among those shares, 90 percent of the value is gains on that stock that have not been taxed because they have not yet been sold. (Under the U.S. tax code, taxes typically accrue only upon “realization” events such as selling stock.) Now suppose that the billionaire borrows $10 billion, which he is only able to do because the banks know he has the (appreciated) assets to repay. We propose that this billionaire pay income tax on his borrowing. The tax would apply to borrowing regardless of whether the billionaire explicitly pledged some assets as collateral or not.

The tax would be easily calculated. Under our proposal, that $10 billion of cash—which is at least implicitly secured by the billionaire’s stock ownership—would be realized and thus become taxable. When income is realized, the tax code subtracts the “basis,” or the amount that the owner paid for the asset and has already paid tax on. We propose using the taxpayer’s basis in his oldest assets, so that taxpayers don’t avoid taxes by selectively pledging their highest-basis assets to borrow and avoid tax. Imposing this “first in first out” assumption for borrowing would considerably lower compliance costs because it requires only valuing the portion of assets whose total value equals the borrowing.

In our example, the oldest tranche of stock purchased by the billionaire for $1 billion is now worth $10 billion. So he would get a basis offset of $1 billion and pay income tax on $9 billion of gains when he borrows $10 billion. In return, when the billionaire sells his stock, he would pay less income tax. That $9 billion of income that is taxed is added to the basis of his oldest stock, making its basis $10 billion. Going forward, should the billionaire borrow additional amounts, then his basis offset is calculated based on his oldest assets not yet revalued under this new borrowing tax.

We would apply this tax, which we detail in our paper and summarize below, to borrowing for any purpose (including mortgages) by U.S. households with assets more than $100 million. The tax would be phased in for households with $100 million to $200 million in assets, with each increase of $1 million of assets beyond $100 million corresponding to a 1 percentage point increase in the share of borrowing covered by the tax. The tax would apply to all future borrowing, as well as borrowing currently on the books. For the tax on existing borrowing, taxpayers would have 5 years to pay, with the ability to pay in five equal installments.

To reduce compliance and administrative costs, the tax on existing borrowing would exempt households with less than $1 million of borrowing. There would also be a yearly de minimis threshold, under which households could borrow without triggering the tax, of $200,000. We selected this threshold to minimize avoidance opportunities while also avoiding costly revaluations of taxpayers’ assets. We further reduce compliance costs by only considering the basis of easier-to-value “major assets,” like stocks and large businesses, rather than homes and art.

To administer the tax, taxpayers covered by the new borrowing tax would report their borrowing in the same way that those with mortgage interest report their borrowing today. Third-party reporting from banks on their lending could back this up, but audits could be sufficient. Everything else in the tax system stays the same. In future years, taxpayers are taxed on increases in net borrowing versus the amount already taxed.

The fiscal reach of closing this loophole

We estimate that U.S. individuals covered by this new tax will have borrowed about $260 billion as of April 2024. This borrowing is explicitly or implicitly backed by assets, whose value we estimate is roughly 55 percent from unrealized gains. Put differently, ultra-wealthy Americans have likely accessed roughly $140 billion of their gains via borrowing, and therefore without paying any income tax. The proposal would tax this use of unsold gains as current income.

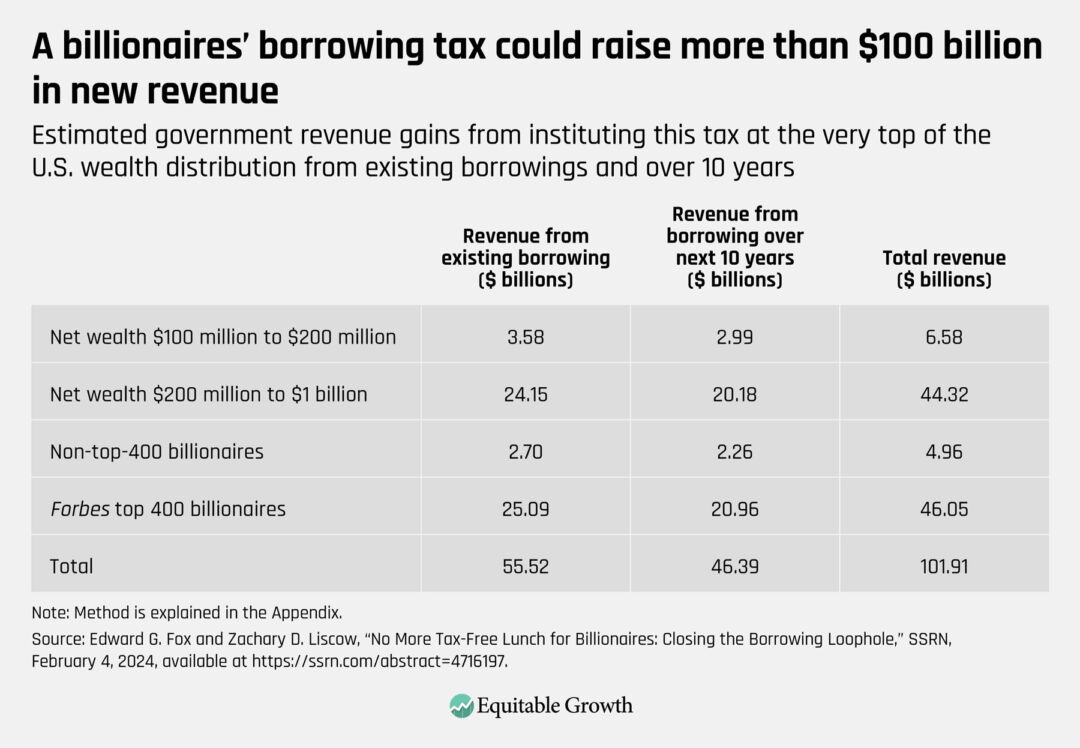

Under the tax rates proposed by the Biden administration, this new tax would raise about $56 billion in income tax from existing borrowing. We estimate that new borrowing over the decade following enactment of the tax would generate an additional $46 billion of income taxes on new borrowing using those same tax rates. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

This static “budget score” does not incorporate some behavioral effects, such as the chance that high-net-worth taxpayers could sell high-basis assets rather than borrow in response to the new tax. That said, the presence of substantial borrowing now, despite the interest costs of borrowing, suggests that there is not a superabundance of high-basis assets to sell.

There are three important fiscal components of our new borrowing tax that are worth emphasizing:

- A majority of the revenue comes from existing borrowing, so a proposal that was just forward-looking would raise far less.

- Our estimate for revenue over the next decade is more speculative, and possibly more upward-biased, than our estimate on existing borrowing because it is possible to avoid taxes on future behavior but not past behavior.

- Exactly half of the estimated revenue comes from billionaires, and 90 percent of that is from the richest 400 individuals in the United States. This makes the tax sensitive to the activity of a very small number of individuals.

The economic benefits of closing this tax loophole

Our proposed billionaire borrowing tax would raise considerable revenue in an equitable and relatively economically efficient way. Specifically, it would:

- Eliminate the tax bias favoring borrowing against assets instead of selling appreciated assets, thereby reducing wasteful tax planning. This tax bias has helped to build up a huge business in which the wealth management divisions of large banks lend to wealthy clients against their securities portfolios. In our paper, we document more than $175 billion worth of these loans as of the second quarter of 2023. Eliminating this bias for individuals covered by the new borrowing tax would eliminate many economically wasteful transactions whose primary purpose is tax avoidance.

- Reduce the tax bias favoring assets that do not regularly produce realized income. The U.S. tax code currently strongly incentivizes owning assets such as growth stocks or land that do not regularly produce realized income over owning assets such as bonds or stocks that pay a regular dividend—even if all the assets have the same risk and produce the same pre-tax return. Part of the reason that high-net-worth taxpayers prefer assets that do not regularly produce realized income is that, under current tax law, taxpayers can access some or all of the unsold gains on their assets by borrowing without triggering income tax. By eliminating this bias, billionaires will be less likely to choose assets with lower pre-tax returns simply because of their tax advantages, likely improving economic outcomes.

- Equalize the tax treatment of income used to fund consumption. Ordinary Americans are typically able to consume only after they pay income tax on their income, which comes primarily in the form of wages. Even when they borrow, they must repay with after-tax dollars. In contrast, the current treatment of borrowing allows wealthy Americans to consume their income without paying taxes on it. Moreover, wealthy Americans may never pay income tax on that appreciation—despite having used it to fund consumption—if they hold their assets until death, at which point the basis is “stepped up” for heirs. Our borrowing tax would equalize the taxation of consumed income for rich and ordinary Americans.

- Minimize distortion in the U.S. tax code by taxing existing borrowing. Importantly, much of the revenue (55 percent) would be raised from funds that have already been borrowed, reducing any potential distortion, because taxing an action that has already happened cannot directly cause any distortion.

Why arguments against closing this loophole are off-base

Importantly, our proposed borrowing tax would likely have little effect on incentives for entrepreneurship, which is one likely argument against it.Economic theory suggests that the efficiency costs of this proposal in terms of a reduced incentive to save or invest for entrepreneurs will be small because they will only be covered by the new borrowing tax if they become enormously wealthy through their ventures.

Entrepreneurs may know that if they do eventually become incredibly wealthy, and thus covered in the future by our proposed borrowing tax, then they will have a low marginal utility of additional after-tax funds—economics parlance for the idea that an extra $100 for a billionaire is worth less than $100 for a lower-income person.

Furthermore, this tax would discourage the current practice of mischaracterizing (higher-taxed) labor income as (lower-taxed) capital income by effectively taxing the entrepreneurial capital income of very high-net-worth individuals covered by the borrowing tax.

Similarly, our proposed borrowing tax would have modest effects on the incentives of those individuals covered by the tax incentives to save or work, another likely line of attack. To be sure, this proposal would likely—but only modestly—increase the effective marginal tax rate on capital income, and there could be small impacts on work efforts as some individuals anticipate slightly increased taxes on the returns to saving earnings from working. Any effects, however, are likely to be small because borrowing represents only a small portion of wealth—about 1 percent to 2 percent, our paper finds.

Furthermore, the resulting disincentive to save is mitigated by the fact that the alternative to saving—consuming—is also taxed a little more by closing the borrowing loophole.

Some may argue that our proposal is unconstitutional because it taxes unrealized income. We explain the legal arguments in more detail in our paper, but briefly, the U.S. Supreme Court has upheld taxes similar to our proposal as a constitutional excise tax on the activity at issue (here, borrowing). Likewise, the existing income tax already taxes apparently unrealized income in a variety of areas, including in partnerships and international taxation, as well as the taxation of some financial products. Finally, borrowing is itself arguably simply a realization of existing gains—the borrowers get cash for their own use, which they could not have obtained but for the gain on their assets.

Yet another likely argument against our proposed borrowing tax is that it would have prohibitively high compliance costs. Our proposal would certainly impose compliance and administrative costs, but we expect these costs to be manageable in part because of the small number of applicable taxpayers. There are only about 35,000 households in the United States that would be covered by this new tax, and fewer than 14,000 of them have more than $1 million in existing debt, according to data collected by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. And, as we noted earlier, about half of the revenue is raised from only 400 individuals.

Furthermore, available estimates suggest that the compliance costs would be modest. Many of the compliance cost issues in our proposal overlap with those that already occur in the estate tax, so that new innovations would not be needed. Estimates of the costs of such valuation vary substantially, but one widely cited estimate by Greg Leiserson, then-director of tax policy at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, calculates the compliance costs of the U.S. estate tax as about 0.2 percent of wealth subject to valuation. Applying that estimate, the compliance costs for our proposal would be about 0.8 percent of revenue raised by the proposal.

But our proposal is even easier to administer than the estate tax—and valuation is easier—because we suggest valuing only major assets, such as stakes in corporations, rather than every asset, some of which can be hard to value. This would further decrease compliance costs.

The billionaire borrowing tax has advantages over other potential new taxes, such as periodic taxes on all unrealized gains or a wealth tax. Our research suggests that the billionaire borrowing tax is more politically feasible than a periodic tax on unrealized gains. In particular, in a representative survey of the population, we find that taxing borrowing is 19 percentage points more popular than taxing unsold gains.

Compared to a wealth tax, the borrowing tax is on firmer constitutional grounds and can feasibly be enacted as a small fix to the current income tax, rather than a new tax on a new base. Taxing borrowing also would raise fewer liquidity concerns compared to a periodic tax on unrealized gains or a wealth tax because borrowers have received cash prior to being taxed. Still, it is difficult to compare the borrowing tax to these much more ambitious proposals, which would have both larger revenue potential and larger administrative costs.

Conclusion

There are many details discussed in our paper on the specific design features that would minimize compliance costs and maximize revenue without harming the entrepreneurial work ethic that helps power innovation in the U.S. economy.

Certainly policymakers who decide to take up our proposal will have to keep in mind that billionaires can afford the most pricey tax lawyers to lower their tax bills. In our paper, we discuss a number of ways to make sure that, as the billionaire borrowing loophole is closed, those hunting for new loopholes are stymied by the law. Others will object to taxing the wealthy unless they actually use their gains, but many of the wealthiest actually do use their gains through the borrowing loophole: They get rich, borrow against those gains, consume the borrowing, and do not pay any tax. This is unfair.

Our nation faces concerningly high wealth and income inequality, and strong revenue needs. Closing the borrowing loophole on the super wealthy would combat both challenges and raise more than $100 billion in a highly progressive and reasonably efficient way.