A new working paper underscores the importance of pass-through businesses, such as sole proprietorships, S corporations, and partnerships, in the forthcoming debate on U.S. tax reform in Congress. The reason: The shift in business activity into pass-through form in recent decades, and a corresponding shift in income reported for tax purposes from wages to business profits, underscores just how consequential the compliance problems would be if Congress were to enact a preferential rate for income from pass-through businesses.

Nearly all of the rise in top incomes since 2000 in the United States has come in the form of business income, according to the new working paper by Matthew Smith of the U.S. Treasury Department; Danny Yagan of the University of California, Berkeley, and the National Bureau of Economic Research; and Owen Zidar and Eric Zwick, both of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and the National Bureau of Economic Research. Business income now accounts for a larger fraction of the income of the top 0.1 percent of income earners than either nonbusiness capital income, such as interest, or wage income. Most of this business income growth comes from pass-through businesses, which do not pay the corporate income tax. Instead, owners of these businesses pay taxes on their share of their firm’s profits on their individual income tax returns. In general, business income is a combination of capital income and labor income, and distinguishing the relative shares can be difficult. Moreover, the line between business income and nonbusiness capital income is itself ambiguous.

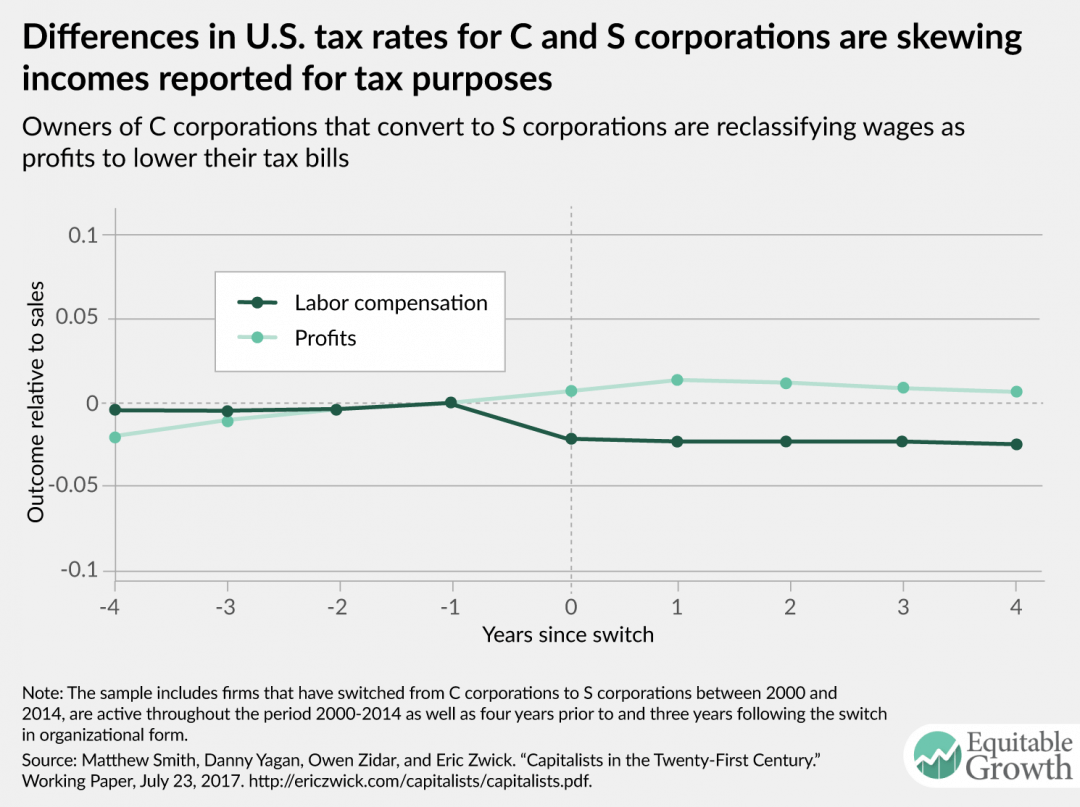

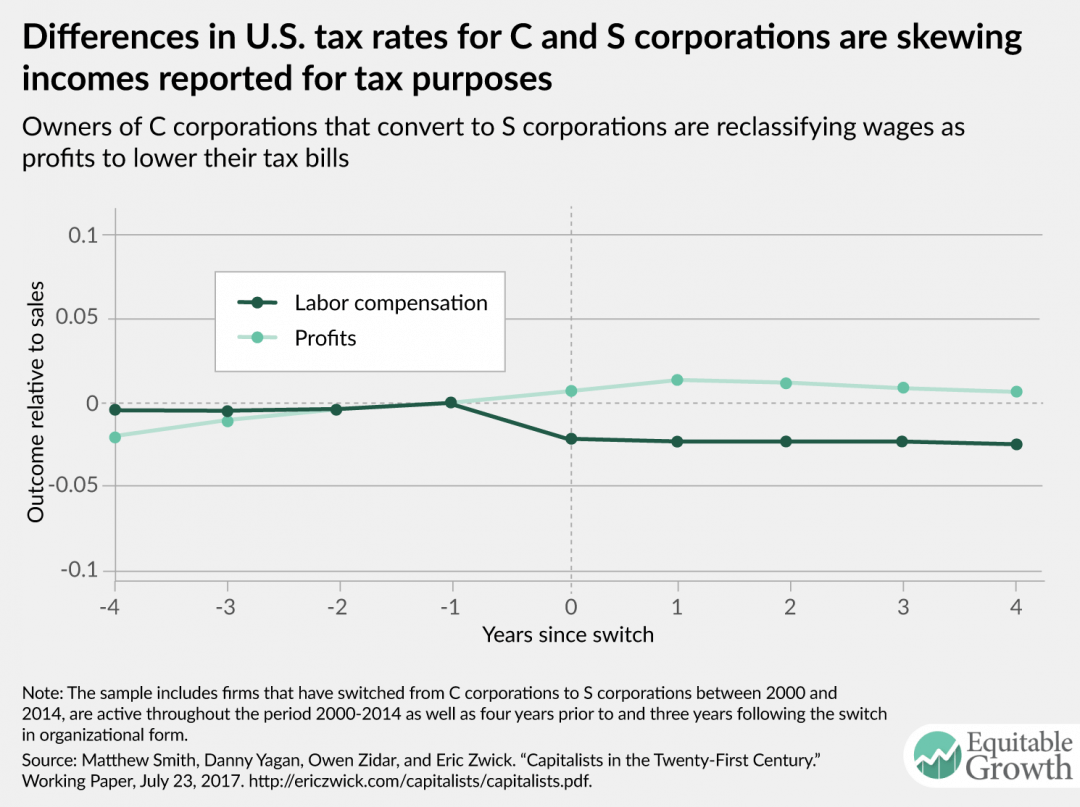

There are many interesting findings in the paper worthy of discussion, but one for policymakers to consider is that business owners show a substantial ability to reclassify income by type, such as from business profits to wages, when there are tax advantages to doing so. The magnitude of this response, even for businesses currently subject to rules intended to discourage such behavior, highlights the potential for compliance problems under a preferential rate for pass-through income—an idea included in several recent tax reform proposals.

The shift of business activity from C corporations—traditional corporations subject to U.S. corporate taxes—to pass-throughs began in earnest after the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which reduced the top personal income tax rate below the top corporate income tax rate. Today, C corporations no longer earn the vast majority of business income, earning less than half of business income as pass-throughs grow in importance. By 2011, 54.2 percent of all U.S. business income was earned by pass-throughs, compared with just 20.7 percent in 1980.

Under current law, active business owners typically face the lowest statutory tax rate on their profits if they conduct business activities in S corporation form. (Other tax considerations, however, may also affect the relative advantages of the choice of form, such as flexibility in allocating income and losses.) If owners “materially participate” in a firm’s operation, then their business income faces only the ordinary income tax—at a maximum rate of 39.6 percent. In contrast, C corporations pay a 35 percent tax on profits, and owners pay additional taxes at the investor level when earnings are distributed—at a maximum rate of 23.8 percent. Wage payments are deducted from business income and taxed at a maximum rate of 43.4 percent at the individual level regardless of the type of business.

Thus, owners of a closely held C corporation would realize tax advantages from paying higher wages and realizing lower profits, while owners of a closely held S corporation would realize tax advantages from realizing income in the form of business profits rather than wages. Both C corporations and S corporations are subject to requirements that wage compensation paid to owner-employees must be reasonable, thus—in theory—limiting the ability of C corporation owner-employees to overstate wages and the ability of S corporation owner-employees to understate wages.

Nonetheless, the data show exactly these kinds of shifts in the 21st century. Studying firms that switch from C corporations to S corporations, authors Smith, Yagan, Zidar, and Zwick observe a substantial reallocation between wages and profits. On average, wage payments fell by 1.95 percent relative to sales during the year of the switch, and profits grew by 1.76 percent relative to sales. (see Figure 1) For dentists’ and physicians’ offices, the swings were more dramatic, with profits increasing 7.81 percent and wages falling 6.36 percent. There was no discernible difference among firms with sales of more than $50 million, but firms with sales of less than $5 million acted much like the full sample of companies surveyed, with wages declining about 2 percent and profits increasing 1.75 percent. Firms with sales of less than $5 million account for the overwhelming majority of the firms in the analysis.

Figure 1

The analysis by the four researchers also finds that the shift of business activity from C corporations to S corporations since the 1980s has reduced the measured share of labor income. The growth in S corporations, and the corresponding shift from wages to profits, skews the measurement of the labor share of income in the corporate sector. The researchers estimate that the decline in the corporate labor share is overstated by 19 percent, as earned income has increasingly taken the form of S corporation profits. Policymakers may soon have to decide if they want to further incentivize this shift through a preferential rate for pass-through businesses.