…Strain also notes that conservatives might ‘have their way with Obamacare’ if ‘the Supreme Court deals it a death blow.’… [Strain’s] wishing for this outcome is morally dubious, and Strain’s counterclaim is unusually weak. ‘In a world of scarce resources, a slightly higher mortality rate is an acceptable price to pay for certain goals–including more cash for other programs, such as those that help the poor; less government coercion and more individual liberty; more health-care choice for consumers…. Such choices are inevitable. They are made all the time.’ This argument about ends is concise, unobjectionable, and completely unresponsive to the situation at hand. If the Supreme Court eliminates ACA subsidies… the federal government will indeed spend less…. But none of the other tradeoffs Strain lists will happen… [no] programs that help the poor… individual liberty will not increase… a wider array of health plans will not materialize. Millions will lose their coverage, insurance markets will collapse…. The moral implications of this outcome are hideous…

Category: Equitablog

Afternoon Must-Read: Ann Friedman: Heather Boushey on Can We Solve Our Child-Care Problem?

What’s interesting about the cost question is that it presumes that no one is paying the costs right now…. We are paying for it, we’re just paying for it in this inefficient way that doesn’t work for families and isn’t good for kids.

Families that can scrape together the money for safe, inspected day-care facilities are forgoing other priorities like saving for retirement or buying new shoes. Families who can’t afford day care are relying on a relative or a neighbor to provide informal care, which may or may not be paid…. Obama’s suggested tax credit is a first step. But he was not proposing a network of state-run, quality day-care facilities–which actually did exist, during World War II, when men were at war and women flooded the workplace…. Nixon vetoed a bill that would have established a network of federally subsidized child-care centers, open to all parents on a sliding scale. He cited the bill’s ‘family-weakening implications’…. The notion that affordable day care is harmful to families sounds downright crazy today…. Sure, personal politics play a role in how each family makes child-care decisions. But in the vast majority of cases, the economics matter far more…

The Future of the European Project, and the Future of the Eurozone: The Honest Broker

J. Bradford DeLong :: U.C. Berkeley and NBER :: April 16, 2013 http://eurofuture2013.wordpress.com/1

My problem this morning is that I have four starting points. Or maybe my problem is that I have five starting points:

I. A Little Dutch History

My first starting point is the history of the Netherlands.

I would have to be more rash indeed than the fifteenth century’s Charles de Valois-Burgogne,2 the last sovereign Duke of Burgundy, to dare to opine about classical Dutch history with Jan de Vries in the room. But my read of it tells me that “political union” is a very vague and sketchy concept indeed. Consider the “political union” of what was surely the strongest power in seventeenth-century Western Europe: the seven United Provinces of the Netherlands that dominated the economy and were the political-military lynchpin of the coalition to contain the aggressive King Louis XIV Bourbon of France. As I understand it, the Dutch political union then consisted of:

- A talk-shop in the Hague, with rather less power than currently held by the organs of the European Union in Brussels and Strasbourg.

- The holding of the seven offices of stadthouder of each of the provinces by the then-current Prince of Orange, whoever that happened to be.

- The fact that the single province of Holland had 60% of the GDP of the whole; and thus could credibly threaten to go it alone, do what was necessary, make a little list of those who had not enthusiastically contributed their share of the resources needed for the common good, and remember.3

That was enough of a political union to support a great power in the seventeenth century that could dominate the seas and orchestrate the best-funded and most powerful military coalition on land as well. Certainly the most memorable piece of bureaucrat and raconteur Samuel Pepys Diary of his life in Stuart-Restoration England is his lament, one night as he watched the warfleet he had spent so much of his career trying to build burn in the Thames estuary, that it seemed to him “the Devil shits Dutchmen!”4

It was enough then. Will that amount of “political union” be enough for Europe today? I do not know. That is my first point–that “political union” is a vague thing, and often you only know that you had it after the fact when you look back, and see that things worked, and that in fact it did not all fall apart.

II. The Classical Political Theory Tradition (and James Madison)

My second starting point is to ask whether a stronger political union than what Europe has now–or than the Dutch Republic of the seventeenth century–is even possible.

Here the place to start is with the classical political tradition plus James Madison. Aristotle of Stagira5 believed that there were and could be no stable democracies, and certainly no good democracies. They were, he thought to the innermost core of his bones, inevitably ruled by faction–so much so that the end-state of democratic politics was a downward spiral of street-fights and purges ending in tyranny. And while this process worked itself out, he thought, at those times when you could get enough people assembled in the Assembly to make a decision, the policies that resulted would be irrational and random. They would decide today that they should execute every adult male in the recently-recaptured city of Mitylene because even the demos had been unwise enough to follow the lead of the aristoi when they had decided to rebel and affiliate with Sparta. They would decide tomorrow–after what must have been an incredibly intense night of bribery by Mitylene’s ambassadors and well-wishers in Athens–that their decision of today had been unwise, reversing themselves, and sending a second messenger-ship across the Aegean to tell the occupying fleet not to do what the previous day’s messenger-ship had commanded them to do.6

Moreover, a democracy would be a bad neighbor. It would be always prepared for aggressive war, for war would bring the demos paid employment in the fleet and their share of plunder as well. Since those who were prosperous and had something to lose did not have a big voice in the government, the government would not pay proper attention to the destructive side of war.

Faction-ridden, irrational, aggressive, militaristic–the classical Athenian democracy, Aristotle said, and for good reason, was very bad news for its neighbors and for itself.

A better alternative government, Aristotle thought, would contain an element of “monarchy”–top-down direction of an elite competition for winning zero-sum status in serving the government and the people–an element in which the ruling principle of politics was “honor”, as Montesquieu would put it 2000 years later7. A better alternative government, Aristotle thought, would even be one of despotism–under despotism the ruling principle would be fear, but at least order would be maintained, and life and prosperity could proceed for all except the few who got crosswise of the despot. Perhaps the best regime would be a “republic”–a government where, again in Montesquieu’s words, the ruling principle would be a positive-sum contest for displaying “virtue” in serving the republic. But such needed to be small–the virtuous cycle of public spirit and public-spirited action could only be maintained in a small community where the behavior of all could be seen. Thus a small city-state with a not-very-democratic mixed-constitution virtue-oriented regime could approximate the Just City, for a while, if you were lucky, if you had a good initial lawgiver, but only as long as the extent of territory did not grow too great.

And if territory did grow too great? Then the good republic was unsustainable, and you would oscillate between monarchy and despotism–as Aristotle must have reflected many times during his life first as tutor to and then as subject of Alexander III Argeios of Macedon, called “the Great”.

Thus the classical tradition says that something like today’s “Europe”–a highly-democratic republic on a continent-wide scale–cannot be a possible good regime. To this James Madison, writing in The Federalist, says: “Not so! Look at the institutions of the second-century BC Aeolian League.”8 (I have not found any other references in secondary works that might have been read by James Madison: he must have trawled deeply indeed to come up with this one as a possible model for what he hoped the United States would become.) It is true that democratic politics tends to be faction-ridden. It is true that political decision-making tends to be irrational–ruled by transitory passions rather than durable interests. But start with a large enough territory, add enough cooling constitutional elements to the orrery of government, construct an eighteenth-century Enlightenment mechanical system of political order with the right properties, and if in its division of power between president, senate, and house of representatives it just happens to mimic the division in Great Britain of power between king, lords, and commons at the accession of King George III Hanover of Great Britain–well then, says Madison, it just might work. The constitutional cooling-off elements tame the irrationality. The extent of territory makes it more difficult for factions, limited to one class in one region, to out-organize the rational upholders of good government.

So Madison, trying to correct Aristotle and found the United States, raises at least the possibility that “Europe” could work–with the right constitutional order.

III. The Necessity of Political Union in the Dark Continent

My third starting point is the absolute necessity of political union in Europe today. It is just too costly and too terrible not to have one: the history of the first half of the twentieth century and then the edge-of-nuclear-terror decades of the Cold War teach that very strongly.

Was it 111 BC that the Kimbri and the Teutones, having moved down from Jutland to what is now Austria and crossed the Danube, decided they would rather cross the Rhine into the land of feta and olives in the Rhone Valley rather than eat Sauerkraut and sausage–or, back then, probably auroch jerky–in Noricum, near what is now Salzburg? So they went. And so they looted, burned, ravaged, killed, and ruled until a decade later they were broken at the battles of Aquae Sextiae and Vercellae by the new-model Roman Republican army commanded by Gaius Marius C. f. seven times consul.9 Ever since then, by my count, it is every thirty-seven years that a hostile army crosses the Rhine going one way or the other bringing fire and sword. The original Swiss–the Helvetii. Julius Caesar. All of those who claimed to be Julius Caesar’s adoptive descendants. The Visigoths heading for Andalusia. Louis XIV commanding his armies to make sure that nothing grows in the Rhinish Palatinate so that his armies attacking Holland have a secure right flank. And, last, Remagen bridge in 1945. Every thirty-seven years, with increasing destructiveness as time passes.

Thirty-seven years after 1945 carries us to 1982. Thirty-seven years after 1982 will carry us to 2019. By 2019 we will have missed two of our appointments with slaughter. We desperately need political union in Europe lest the bad old days from 111 BC to 1945 come again as we once again fall victim to the tragedy of great power politics10. That means that politicians find some way to union–so that differences are thrashed out in conference rooms in Brussels and Strasbourg rather than in the streets with Molotov cocktails, submachine guns, armed drones, and worse. That is the necessity.

:

IV. Kindlebergian Hegemony?

The fourth starting point: return to the question of the possibility of a unified Europe. A presupposition of the Madisonian hope for a durable and well-functioning democratic government of great extent and territory was a certain original cultural not homogeneity but affinity: people in Georgia had to look at people in Maine as friends and allies by default, with the growth of faction needed to convince them otherwise. Suppose that is lacking. What then?

You then have to jury-rig something. You then have to hope for or to somehow generate a benevolent Kindlebergian hegemon11–some actor large enough to be the first-mover, to set the policy, because it is our way or the highway. This requires a willingness on the part of the hegemon to follow-through on its policy commitments–to mean it when it says “our way or the highway”. This also requires a willingness on the part of the hegemon to be exploited to some degree–to let others free-ride on the public goods of international civil, political, and economic order that it establishes and provides. The hegemon has to be large and powerful enough to have an overarching interest in those international public goods. And it has to value public order, or public order plus various exorbitant-privilege12 benefits of hegemony, more than it feels taken advantage of by the free-riding.

Absence of a hegemon is, in brief, Kindleberger’s theory of why the history of the North Atlantic economy between 1919 and 1939 was such a tragedy: Britain no longer but the United States not yet willing and perhaps not yet able to be the hegemon. That leads one to fear that perhaps, at the deepest level, the central problem with Europe today is that the United States is no longer the Cold-War North Atlantic benevolent hegemon it once was, but that Germany has not or has not yet stepped into that benevolent-hegemon role–or because of German history and German attitudes would not be tolerated by the rest of Europe in that role.

V. External Pressure?

The fifth and last starting point is what Madison left out: who the Aetolian League actually worked. It did work. It was remarkably stable. It had an executive. Its executive had powers and made decisions. It could command rather than request from its city-state members–and its commands were obeyed. But the Aetolian League was impossible to imagine without Macedon to the north. A hostile great power on its borders was essential to induce the surrenders of sovereignty needed for the Aetolian League to function. Analogously, a hostile Great Britain that would not have minded scooping up an ex-colony or two that wished to return to the bosom of Westminster–and confiscate the fortunes, and perhaps the lives and sacred honor–of the politicians who had led them astray into independence was essential to induce the surrenders of sovereignty needed for Madison’s constitution and Madison’s United States. In the absence of potentially hostile Great Britain, it is very difficult to imagine the politicians of Rhode Island agreeing to their voice being all-but-drowned-out in the lower house of representatives, and impossible to imagine the politicians of Virginia and Massachusetts agreeing to their voice being reduced to no louder than Rhode Island’s voice in the upper house of the senate.

There is a story that when Paul-Henri Spaak was Secretary-General of NATO, he was asked if it would not be a good idea to erect statues to the founders of what was then becoming the European Union–the ECSC, the EEC, the EC, et cetera. His response, supposedly: “What a wonderful idea! There should be a fifty-foot tall statue of Josef Stalin in front of the Berlaymont Palace to remind us of why we are all here!” It was the Red Army’s Group of Soviet Forces in Germany at the Fulda Gap that concentrated people’s minds behind the ideas of the Monnets and the Schumanns most powerfully in the decades after World War II. That potentially-hostile superpower created a powerful desire on the part of many to make sure the ECSC, then the EEC, then the EC, and finally the EU succeeded.

And all of that vanished at the start of the 1990s–although there is a chance that we may in a few years be thanking Vladimir Putin for bringing it back.

Where do all five of these starts leave us?

VI. The Euro and the Lessons of 1919-1939

We ought, when we started the euro, have remembered the principal lessons of 1919-1939.

First, there is the lesson that John Maynard Keynes tried unsuccessfully to teach Harry Dexter White at Bretton Woods: that in order for an international market economy to be stable and prosperous, adjustment to macroeconomic disequilibrium needs to be symmetrically undertaken by both surplus and deficit regions, and not by deficit regions alone.[][]

When Christina Romer was in office back in 2010, she would stand up at OECD meetings and say: “What Europe needs to do in order to solve its financial and structural crises is not just a shift to sounder finance and more public austerity in the periphery, but pro-growth policies in the core.” Everyone would say “yes, yes” and applaud. But what Christie would mean by “pro-growth policies in the core” is for a proportional share of the adjustment burden to be undertaken by surplus regions, which would mean 4%/year inflation in Germany and Holland. That would have been required for 2%/year inflation in the Eurozone as a whole, and thus for structural adjustment in Southern Europe to take place without grinding wage deflation. Deflation in the periphery and only 2%/year inflation in Germany means you won’t hit your 2%/year inflation target for the Eurozone as a whole. And you won’t get structural adjustment until generations have passed.

Second, if an international economy is to have any chance of avoiding crises, an integrated banking system requires an integrated banking supervisory system. Either you have to cut banking systems off from each other and run credits and debits through sovereigns–and then backstop those sovereigns, as the government of Austria was not backstopped when it tried to support the Credit-Anstalt back in 1931–or if you let banks hold assets and liabilities across national borders the supervision with an eye toward minimizing and then dealing with systemic risk needs to cross national borders and be global as well.

Third, for crises to be successfully managed, the lender of last resort must truly be a lender of last resort. The first part of the Bagehot rule is lend freely–and the lending must be truly free, and truly unlimited in quantity. The lender must be able to create whatever asset the market thinks is their port-of-safe-refuge and do so in whatever quantities the market thinks it might every possibly demand. It cannot get hung up on, say, Pierre Laval’s desire to win points for himself in French domestic politics by vetoing Austro-German plans to increase the tax base via customs union as a way of making it sustainable for the German Weimar Republic’s Reichbank to rescue the OeNB which was trying to rescue the Credit-Anstalt which had tried to moderate the Great Depression in the Danube basin by continued lending into the post-1929 downturn.

Fourth, in order for any monetary union or fixed exchange-rate union larger than the size of a true optimum currency area to survive, it must be willing to undertake large-scale fiscal transfers to compensate for the absence of the prohibited exchange rate movements that would otherwise shift terms of trade and rebalance the economy. Monetary union on a scale as large as the Eurozone requires large fiscal transfers, which are unthinkable without some operating and functioning form of political union.

I do know that those of us who were, back at the start of the 1990s, watching the project of the establishment of the Eurozone assumed that the establishment was being carried out by people who had learned these lessons. They were, after all, obvious–or maybe obvious only to people who watched international finance, or maybe obvious only to people with Ph.D.’s in economics who had written their dissertations in international finance, or maybe obvious only to those few of us who had made a relatively deep study of 1919-1939. We now find that the Princes and Princesses of Eurovia today do not appear to have learned these lessons. History taught the lessons. It taught them, I thought, fairly convincingly. But were the Princes and Princesses of Eurovia listening?

How did this come about? Why didn’t Maastricht set up a single Eurovia-wide banking supervisor to align financial regulatory policies across the Eurozone? Why didn’t Maastricht explicitly set up the fiscal transfer funds that, it was clear then, would be needed whenever some regional component of Eurovia were to fall into a deep recession–as some regional component surely would at some time? Why did Maastricht leave a good deal of lender-of-last-resort authority in the hands of national governments that could not print money–could not create the safe asset for the system–and implicitly task them with responsibility for their banking system? And why, given that one country’s exports are another country’s imports by necessity–and given that the United States will not always be enthusiastically the possessor of a hyper-strong dollar and the importer of last resort to guarantee full employment throughout Europe–does not the adoption of policies in Eurovia deficit regions to shrink their imports automatically trigger the adoption of corresponding policies in Eurovia surplus regions to boost their imports?

Part of the reason was the general belief in the Berlaymont and elsewhere that requiring the specification of what were seen as ancillary details at Maastricht would postpone the project for years if not decades. The logic of events, it was thought by many, would inevitably lead to the development of the missing pieces: first the common banking regulatory union, then over time the fiscal union, and then the political union necessary to make the fiscal union durable and acceptable, and then the making of the Europeans needed to populate the political union and keep it stable against centrifugal tendencies. And as for the fear that surplus countries might be reluctant to share in adjustment–well, back in 1992 it must have seemed extremely unlikely that politicians anywhere in Europe would ever have turned down an IMF-blessed demand that they expand their economies and reduce their levels of unemployment.

Surely when the crisis came we thought–at least those of us who worked in the U.S. Treasury and talked to the IMF thought–if it is indeed necessary that some European countries expand in the interest of structural adjustment, the IMF blessing of that expansion would neutralize any domestic political opposition to “sound finance”. Yet we seem today to live in a very different world indeed from the world that we thought then that we did.

And, of course, underlying everything at Maastricht and in those Helmut Kohl post-Cold War years was a background gestalt that Maastricht was in large part Germany renewing its commitment to the continued and further integration of Europe in the aftermath of the very strong support given by the rest of continental Europe to the Bundesrepublik’s absorption of the German East. If it turned out that someone had to pay somehow somewhen for the sin of not clearly foreseeing the consequences of the single currency and the Eurozone, this political support by the rest of continental Europe in the face of some skepticism as to the wisdom of immediate German unification from the United States and Russia meant that the rest of Europe had a very deep well of credit with Germany on which it could draw. Germany would remember. And Germany would be eager to pay.

It may well all work out. Fifty years from now historians may well be writing that Maastricht was a gamble–and was, like Waterloo, a near-run thing–but a gamble that in the end paid off after all. “After all”, historians may say in 2063, “it has now been 108 years since an army crossed the Rhine with fire and sword, and the unforeseen costs of Maastricht are a very small payment for an insurance policy against that eventuality”. There may still be large differences in prosperity between Europe’s core and its periphery. But come 2063 Europe as a whole may well be so rich that these are and are seen as second-order concerns at most. In 2063 Northern Europeans may still grumble that Southern Europeans lack a proper work-ethic, but when they do so they may do so as they pay through the nose for the amenities of all of their Mediterranean vacations.

After all, being taxed a bit to support the common European project has large benefits. The Kimbri and the Teutones never got to enjoy the feta and the olives and the sunshine. We have every reason to think that the Northern Europeans of 2063 will.

Perhaps.

Perhaps not.

But right now, it looks to me as though history did indeed teach the lesson, but that while history was teaching the lesson the Princes and Princesses of Eurovia today were too busy texting on their cell phones to pay any attention.

http://delong.typepad.com/files/20130416-brad-delong-22future-of-the-euro22-eichengreen-conference-talk.m4a | Notes

4256 words

Did credit really replace wage growth in the mid-2000s?

The bursting of the U.S. housing bubble in 2006 and 2007 revealed a mountain of debt that households had accumulated in the preceding years. This massive debt overhang obviously had severe consequences for the U.S. economy, which is why economists and policymakers have spent the years since the bust arguing about the best way to deal with the overhang.

But with households starting to increase their leverage once again, perhaps reconsidering the dynamics that led to the housing bubble might be more useful. A rush of new middle and high income mortgage borrowers may have been a significant factor in the run up to the housing crisis of 2006 and 2007, according to a new paper. This new analysis challenges the findings of other recent research into the origins of the crisis that suggest lending to lower-income borrowers who were experiencing no wage gains in this period was the primary cause.

So first, let’s briefly present the currently favored theory. One argument that garners quite a bit of attention is from economist Raghuram Rajan, now the governor of the Reserve Bank of India but formerly of the International Monetary Fund and the University of Chicago. In his book, Fault Lines, Rajan argues that governments loosened credit so that low-and medium-income households could borrow to make up for stagnant wage growth.

Economists Atif Mian of Princeton University and Amir Sufi of the University of Chicago build on Rajan’s research, finding evidence that credit and relative wage growth in zip codes were negatively correlated—meaning that credit grew as relative wages went down—as the housing bubble inflated. But importantly, Mian and Sufi didn’t look at individual lenders, only the activity in the zip code as a whole.

The new National Bureau of Economic Research working paper does look at individual borrowers. The authors, economists Manuel Adelino of Duke University, Felipe Severino of Dartmouth College, and Antoinette Schoar of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology analyze individual mortgage and income data from the Internal Revenue Services to tackle this question. They find similar results to Mian and Sufi on a variety of questions. Their data, for example, also show that credit flowed to areas where housing prices increased the most and that there was a negative correlation between relative income growth and credit growth at the zip code level.

But when Adelino, Severino, and Schoar look at the individual level they find a positive correlation. In other words, mortgage credit was going to individuals who were seeing positive income growth. The authors show that the borrowers who were receiving the credit weren’t those at the bottom of the income ladder, but rather those at the middle and the top. And the credit growth appeared to be in proportion to income growth: The debt-income-ratio didn’t appear to change much during the bubble years.

So were the middle class and the rich were taking out much larger loans than before or more mortgages? According to Adelino, Severino, and Schoar it was both, but more so the latter. They find that the effect on the extensive margin, meaning new borrowers entering the market, was larger than the effect on the intensive margin, or borrowers increasing the size of loans. As the title of their paper says, the composition of home buyers changed during the period.

Adelino, Severino and Schoar’s paper would seem to indicate that what caused the run up in mortgage debt wasn’t due to a change in “lending technology” such as securitization or looser government policies. Rather, the debt was built by the same kind of bubble dynamics that leads to investors betting that an asset will never lose value. Which story is true is still up for debate, but it could just be that this time wasn’t no different after all.

Robert Waldmann on the Fiscal Cliff and Fiscal Multipliers: Focus

I was writing a piece about the rather strange belief I hear that the failure of the U.S. economy to fall into a recession in 2013-2014 demonstrates that fiscal multipliers are relatively small. But Robert Waldmann did it first, and better than I was doing:

…of how fiscal tightening in the first quarter of 2013 (the fiscal cliff in January and Sequestration in March) was followed by decent growth in the second half of 2014…. I have two more thoughts. First… there was a contractionary fiscal shock… and a contractionary forward guidance of monetary policy shock…. No matter what one’s view of the relative effectiveness of fiscal policy and of non standard monetary policy at zero lower bound, one would expect disappointing growth… very disappointing compared to forecasts of rapid growth reducing the output gap as all past US output gaps have shrunk.

Second the lags people use are getting extremely long and variable. The debate was triggered by the surprisingly high growth in the third quarter of 2014… six quarters after…. This is very odd data analysis…

And:

…have argued that Keynesians predicted that the fiscal cliff January 2013 and sequestration March 2013 would cause a recession. A fairly large number of Keynesian economists have denied personally making that prediction…. it is fairly easy to decide if the orthodox Keynesian view was that 2013 fiscal contraction would cause a recession… [because] official… forecasting models range from new Keynesian (with added epicycles) for the Bank of England, to paleo-Keynesian for the Fed…. Official forecasts… give a hostage to fortune….

Strikingly the CBO seems to have qualitatively nailed it. The report starts:

Economic growth will remain slow this year, CBO anticipates, as gradual improvement in many of the forces that drive the economy is offset by the effects of budgetary changes that are scheduled to occur under current law. After this year, economic growth will speed up, CBO projects, causing the unemployment rate to decline and inflation and interest rates to eventually rise from their current low levels.

They didn’t predict the polar vortex, but seem to have done OK…. The CBO didn’t forecast a recession…. ‘In November 2012, the CBO specifically addressed the “fiscal cliff” here: http://www.cbo.gov/publication/43694 and predicted a very mild recession IF Congress did absolutely nothing to moderate or prevent the tax hikes and budget cuts scheduled for January 2013. Of course, we didn’t go off the cliff. Instead, we went on a moderated glide path.’…

The Fed… is a methodologically and ideologically diverse bunch… but it sure looks as if they all or almost all expected an acceleration of GDP growth from 2013 to 2014… no mention of any possible recession in 2013…. [The] Federal Bank of New York staff forecasts… “Significant fiscal drag in 2013”, showing they are Keynesian. No recession forecast…. A year later, May 2013, with funds actually sequestered, the FRBNY staff seemed not to have changed their views…. I don’t see any special challenge to the CBO New York Fed orthodoxy in the data.

Nighttime Must-Read: Kenneth Thomas: What Is Noah [Smith] Thinking?

…purporting to show that things aren’t so bad for the middle class… immediately shows us a chart of median household income. Stop right there….. We need to look at individual data, aggregated weekly… to know what’s going on…. The individual real weekly wage is still below 1972 levels, [so] households… have traded time and debt for current consumption. This is not an improvement in the middle class lifestyle…. Richard Serlin points out that we also need to consider risk…. The middle class is less secure than it was in 1972. Noah has lots of interesting things to say, and you should check out his blog if you haven’t already. But this is an error on his part, and I don’t understand what he’s thinking.

Things to Read on the Morning of January 24, 2015

Must- and Shall-Reads:

- : Time to get serious about bank reform: After the financial crisis, governments staved off a second Great Depression – too well. This triumph let them duck tough reforms

- : GOP Rep. Tom McClintock: Keep minimum wage low ‘for minorities’ who aren’t worth more than $7 an hour

- : Medicaid Expansion

- : Unicorn Bloodbath: VC Bill Gurley Sounds The Alarm, Again

- : GOP senator Joni Ernst who boasted about her family’s self-reliance received $460K in federal subsidies

-

: Hall of Mirrors [Audio] :: London School of Economics :: Public lectures and events -

: The Midwest’s climate future: Missouri becomes like Arizona, Chicago becomes like Texas: “The bipartisan trio of climate risk prognosticators for the business community–Michael Bloomberg… Hank Paulson, and… Tom Steyer–are back…. A higher prevalence of extremely hot temperatures could severely impact corn and wheat production, the report warns, unless we take serious evasive action…. By 2100… the more likely range for losses, says the document, is 11 to 69 percent…” -

: The Upshot: “That’s the power of The Upshot, an online news and data visualization portal on the New York Times’ website… entrust[ed]… to the paper’s former Washington bureau chief and economics columnist David Leonhardt…. To Leonhardt, The Upshot is more of a laboratory where he can lead a team of 17 cross-disciplinary journalists to rethink news as something approachable and even conversational. The goal: to enable readers to understand the news and by extension, the world, better. publisher. But we live in the puppy-GIF era…”

Should Be Aware of:

- : How working women, cheap cars, and Starbucks killed carpooling

- : “Romney appears to have been body-snatched—perhaps by the ghost of Ted Kennedy…. What’s next? Supporting gay rights, gun control, and abortion rights? (Or, in his case, going back to supporting gay rights, gun control, and abortion rights)…”:

- The Earl Grey Tea House

- : The AI Revolution: Road to Superintelligence

-

: Why the Plaintiffs in King Are Wrong: “A third constitutional defect in this ObamaCare legislation is its command that states establish such things as benefit exchanges, which will require state legislation and regulations. This is not a condition for receiving federal funds, which would still leave some kind of choice to the states. No, this legislation requires states to establish these exchanges or says that the Secretary of Health and Human Services will step in and do it for them. It renders states little more than subdivisions of the federal government.” -

: Back On The Veldt, People Who Didn’t Attribute Innate Personality Differences To Gender Were All Eaten By Wolves. What Were Wolves Doing On The Veldt? Who Can Tell?: “The Atlantic… an article… ‘The Secret To Smart Groups: It’s Women’. Researchers… quantifying the ‘intelligence’ of small groups… found… it was less strongly related to the individual intelligence of the group members than the average… capacity to understand what other people are feeling…. Women are on average better at social sensitivity…. Look: I completely believe that social sensitivity is terribly useful in making a group accomplish anything…. I’m also perfectly ready to believe that women are on average much better at it. But come on…. If you want a smarter group, you want more socially sensitive members, not more women… just choosing women blindly isn’t–I know some deeply socially insensitive women…. The researchers themselves say this kind of sensitivity is a learned skill…. Could the headline of the article maybe be about how this is a skill people should be focusing on improving, rather than about how one gender is just better at it than the other? Feh. (It is kind of relaxing, for once, to come up with a stereotypical gender difference where I personally come up feminine, though. While I’m deeply socially awkward in general, I kick ass at… ‘what emotion is this set of eyes expressing’… I do spend a fair amount of time at work massaging other people’s states of mind so as to keep the work progressing…)”

Morning Must-Listen: Barry Eichengreen: Hall of Mirrors

Weekend reading

This is a weekly post we publish every Friday with links to articles we think anyone interested in equitable growth should read. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week we can put them in context.

Monetary policy

Matthew C. Klein on the rise of borrowing in dollars outside of the United States and the implications for monetary policy. [ft alphaville]

Annie Lowrey on how central bankers should heed the lessons of the rap duo Outkast. [new york]

Capital and taxation

Peter Orzag argues that profit-sharing for employees can help alleviate the problems stemming from the decline of the labor share of income. [bloomberg view]

Justin Fox writes on the high price of avoiding taxes and corporate inversions. [bloomberg view]

The labor market

Allison Schrager looks at the data on labor force participation and finds that the dropouts are mostly students or retirees from high-income households. [businessweek]

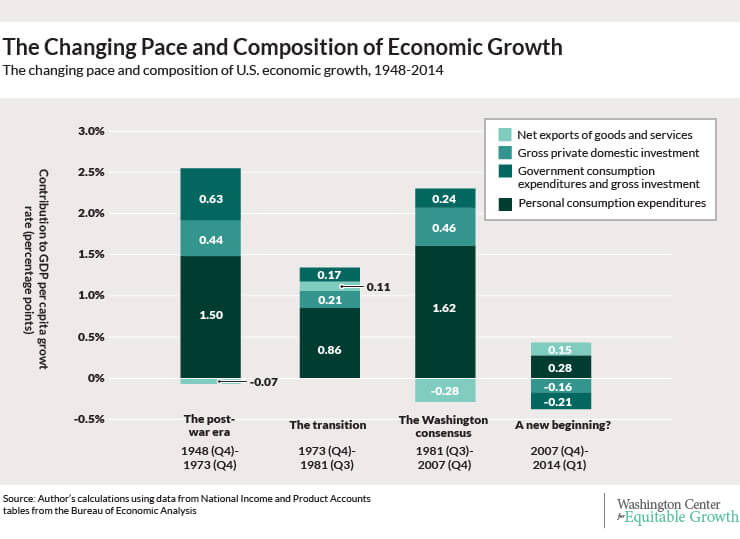

Friday Figure

Morning Must-Read: Chris Mooney: The Midwest’s Climate Future

for the business community–Michael Bloomberg… Hank Paulson, and… Tom Steyer–are back…. A higher prevalence of extremely hot temperatures could severely impact corn and wheat production, the report warns, unless we take serious evasive action…. By 2100… the more likely range for losses, says the document, is 11 to 69 percent…