…The fact that currently wealthy Americans have not, in general, inherited their wealth follows logically from the fact that, in their parents’ generation, there weren’t comparable accumulations…. Given the pattern of highly unequal incomes, and social immobility observed in the United States today, we can expect inheritance to play a much bigger role in explaining inequal…. Inherited advantages in the patrimonial society predicted by Piketty will include direct transfers of wealth as well as the effects of increasingly unequal access to education, early job opportunities and home ownership.

Category: Equitablog

Must-Read: Katharina Knoll, Moritz Schularick and Thomas Steger: Global House Prices, 1870‐2012

Must-Read: : Global House Prices, 1870‐2012: How have house prices evolved over the long‐run?…

…This paper presents annual house prices for 14 advanced economies since 1870. Based on extensive data collection, we show that real house prices stayed constant from the 19th to the mid‐20th century, but rose strongly during the second half of the 20th century. Land prices, not replacement costs, are the key to understanding the trajectory of house prices. Rising land prices explain about 80 percent of the global house price boom that has taken place since World War II. Higher land values have pushed up wealth‐to‐income ratios in recent decades.

Today’s Must-Must-Read: Georg Graetz and Guy Michaels: Robots at Work

…there is almost no systematic empirical evidence on their economic effects. In this paper we analyze for the first time the economic impact of industrial robots, using new data on a panel of industries in 17 countries from 1993-2007. We find that industrial robots increased both labor productivity and value added. Our panel identification is robust to numerous controls, and we find similar results instrumenting increased robot use with a measure of workers’ replaceability by robots, which is based on the tasks prevalent in industries before robots were widely employed. We calculate that the increased use of robots raised countries’ average growth rates by about 0.37 percentage points. We also find that robots increased both wages and total factor productivity. While robots had no significant effect on total hours worked, there is some evidence that they reduced the hours of both low-skilled and middle-skilled workers.

The problem of too much stuff sloshing around the global economy

Sometimes there can be too much of a good thing. Right now, in the global economy, there appears to be far more commodities available than current demand merits. This glut is matched by too many available workers and too much capital sloshing around the global economy. In the Friday edition of The Wall Street Journal, Josh Zumbrun and Carolyn Cui highlight these gluts, but the question underlying the article is whether these oversupplies are the result of increasing supply or due to insufficient demand.

First, let’s point out that the trends here are certainly different for different aspects of the glut. Take oil. The rapid decline in oil prices during 2014 was one of the biggest economic stories of the year. But what exactly caused that decline? In another piece, Zumbrun highlights research from the International Monetary Fund on the cause in the decline of oil prices. According to the IMF, the decline was first caused by a slowdown in economic activity (a reduction in demand) before increased supply of oil contributed an increasingly large role in the price decline.

That explanation might not hold for other commodities in the current situation. In the copper market, for example, technology can’t lead to a sudden expansion of copper supply analogous to the rise of fracking that has contributed to the increased oil supply. The decline in copper prices is almost certainly a function of declining demand, especially from China.

Then there’s capital. Interest rates are very low right now due to the monetary easing done to counteract the Great Recession and the weakness in many parts of the world, such as Europe. In other words, the price of capital is quite low right now because of demand. Just as the United States economy appears to be healing, Europe, China, and other weak spots could start growing at a healthy clip and that would reduce the glut of capital.

That possibility assumes that the mismatch between the supply and demand of capital is a short-term phenomenon. Given enough time, the price of capital will adjust so that’s there’s no oversupply or insufficient demand. But as Zumbrun and Cui note in their piece, there’s an argument, advanced by former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, in which nominal interest rates need to drop below zero for the imbalance to disappear. And if you’ve paid attention to Europe in recent months, you’ve seen interest rates do exactly that.

Summers has argued that this imbalance has been a feature of the global economy for years and has been responsible for the decline in interest rates and some the bubbles of the late 20th and early 21st century. Ben Bernanke, the former Federal Reserve Chair, has argued that the imbalance is a fleeting feature of the global economy and will abate as the economy recovers.

When it comes to labor, this particular glut might be the one that is most clearly a long-run trend. The new waves of workers from the former Soviet Union, China, and India have dramatically increased the supply of labor in the global market. This increase plus the increased opening of the U.S. economy is one potential cause of the decline of the labor share of income in the United States.

Whether these gluts are something economists understand as a strange, but one-off event or as a major feature of our times will have a large impact on how we understand our economic future.

Just What Are the Risks That Alarm Ken Rogoff?

As I say, repeatedly: everything that Ken Rogoff writes is very interesting, nd almost everything is correct.

But.

This part of Ken Rogoff’s piece appears to me to be very much on the wrong track:

small changes in the market perception of tail risks can lead both to significantly lower real risk-free interest rates and a higher equity premium…. Martin Weitzman has espoused a different variant of the same idea…. Those who would argue that even a very mediocre project is worth doing when interest rates are low…. It is highly superficial and dangerous to argue that debt is basically free. To the extent that low interest rates result from fear of tail risks a la Barro-Weitzman, one has to assume that the government is not itself exposed to the kinds of risks the market is worried about, especially if overall economy-wide debt and pension obligations are near or at historic highs already. Obstfeld (2013) has argued cogently that governments in countries with large financial sectors need to have an ample cushion, as otherwise government borrowing might become very expensive in precisely the states of nature where the private sector has problems…

First, we need to be clear about what the relevant tail-risk states that Ken Rogoff is talking about are. There are definitely potential future states of the world in which nothing has value except for sewing machines, ammunition, and bottled water; in which even your gold Krugerrands are sources of risk as they attract theft and violence rather than stores of value. But those future states of the world are irrelevant for pricing financial assets because all financial assets–even government bonds–are worthless in them. Thus worry about those states of the world provides no reason for a government to issue debt. They are not the relevant tail-risk states.

The relevant tail-risk states are those in which (a) there is still an economy, (b) there is still a government, (c) the government is either imposing taxes to amortize its debt or choosing some costly and dissipative default procedure, and yet (d) investments in corporate debt (and presumably corporate equities) are strongly negative in net terms. It is those states of the world that people think that government debt provides insurance against. It is insuring against those states of the world that have driven the prices of government debt sky-high. And it is with respect to those states of the world that Ken Rogoff claims that the actual costs to the government at borrowing at those very low interest rates are high because:

the government is… itself exposed to the kinds of risks the market is worried about, especially if overall economy-wide debt and pension obligations are near or at historic highs already. Obstfeld (2013) has argued cogently that governments in countries with large financial sectors need to have an ample cushion, as otherwise government borrowing might become very expensive in precisely the states of nature where the private sector has problems…

And thus, even though it was sold at a high price and carries a low interest rate, the issuing of government debt is very expensive to the government: when the time comes in the bad state of the world for it to raise the money to amortize the debt, it finds that it really would very much rather not do so.

It is clear if you are Argentina or Greece what the risk is: it is of a large national-level terms-of-trade or political shock, something that you can insure against by investing in the ultimate reserves of the global monetary system.

If you are the United States or Germany or Japan or Britain, what is the risk?

What is the risk that cannot be handled at low real resource cost by a not-injudicious amount of inflation, or of financial repression?

Weekend reading

This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles we think anyone interested in equitable growth should be reading. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week we can put them in context.

Links

Eduardo Porter argues that something has gone wrong in the labor market. [nyt]

Jared Bernstein is all for higher productivity growth, but he’s not sure it’ll necessarily resulting in higher middle-class incomes. [on the economy]

Tony Yates is, let’s say, less than convinced by John Taylor’s argument that loose monetary policy caused the Great Recession. [long and variable]

Arin Dube writes about the idea that social safety net programs are subsidies for employers. [arin dube]

The 1.5 million missing black men in the United States, an incredibly important fact for debates about inequality, highlighted by Justin Wolfers, David Leonhardt, and Kevin Quealy. [the upshot]

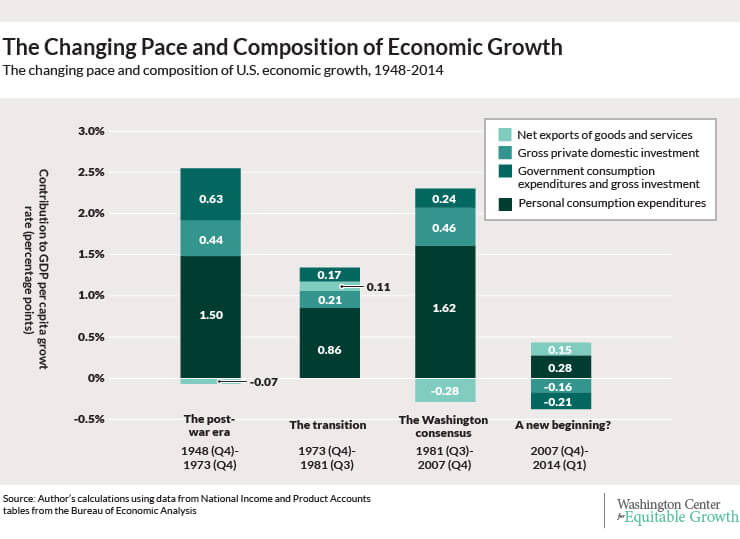

Friday Figure

Figure from “A post-war history of U.S. economic growth,” by Nick Bunker

Must-Read: Timothy B. Lee: The Trans-Pacific Partnership: Great for Elites. Is It Good for Anyone Else?

…where powerful interest groups try to use trade rules to overrule democratically elected governments…. The WTO’s dispute-settlement process… puts pressure on countries to actually keep the promises they make in trade deals…. But the complex, secretive, and anti-democratic way the TPP is being crafted rubs a lot of people the wrong way….

We expect the laws that govern our economic lives will be made in a transparent, representative, and accountable fashion. The TPP negotiation process is none of these — it’s secretive, it’s dominated by powerful insiders, and it provides little opportunity for public input. The Obama administration argues that it’s important for TPP to succeed so that the United States — not China — gets to shape the rules that govern trade across the Pacific. But this argument only makes sense if you believe US negotiators are taking positions that are in the broad interests of the American public. If, as critics contend, USTR’s agenda is heavily tilted toward the interests of a few well-connected interest groups, then the deal may not be good for America at all…

Must-Read: Zeynep Tufekci: The Machines Are Coming

…but also read their expressions. They can classify personality types, and have started being able to carry out conversations with appropriate emotional tenor. Machines are getting better than humans at figuring out who to hire, who’s in a mood to pay a little more for that sweater, and who needs a coupon to nudge them toward a sale. In applications around the world, software is being used to predict whether people are lying, how they feel and whom they’ll vote for. To crack these cognitive and emotional puzzles, computers needed not only sophisticated, efficient algorithms, but also vast amounts of human-generated data, which can now be easily harvested from our digitized world. The results are dazzling. Most of what we think of as expertise, knowledge and intuition is being deconstructed and recreated as an algorithmic competency, fueled by big data. But computers do not just replace humans in the workplace. They shift the balance of power even more in favor of employers….

I recently had a conversation with a call center worker from the Philippines. While trying to solve my minor problem, he needed to get a code from a supervisor. The code didn’t work. A groan escaped his lips: ‘I’m going to lose my job.’ Alarmed, I inquired why. He had done nothing wrong, and it was a small issue.‘It doesn’t matter,’ he said. He was probably right. He is dispensable…. This is the way technology is being used in many workplaces: to reduce the power of humans, and employers’ dependency on them….

Optimists insist that we’ve been here before, during the Industrial Revolution, when machinery replaced manual labor, and all we need is a little more education and better skills. But… one historical example is no guarantee of future events…. It’s easy to imagine an alternate future where advanced machine capabilities are used to empower more of us, rather than control most of us. There will potentially be more time, resources and freedom to share, but only if we change how we do things. We don’t need to reject or blame technology. This problem is not us versus the machines, but between us, as humans, and how we value one another.

Must-Read: Nick Bunker: What Is the Right Size and Purpose of the U.S. Financial System?

…[Noah] Smith notes that they all [pieces of finance]… take savings and turn them into investments…. Size might not be the only relevant question when it comes to the financial sector. The structure and the purpose of the financial system and its constituent parts are important to consider as well. If finance acts like an irrigation system for the broader economy, we need to question not only how big specific pipes are but also where those pipes eventually lead…

Must-Must-Read: Adam Kotsko: The Good Inequality

…They want inequality, but the good kind, the justified kind. Hence it is plausible that someone could rail against the power of the 1% and yet still get snippy: “They want $15 an hour for flipping burgers?!” The good inequality now would be based on getting a college education, but whether you received that education and the degree of quality would be based solely on your merits and efforts…. It’s weird the directions that meritocracy starts taking you, though. Have you ever noticed how many firm believers in meritocracy seem to assume that taking race into account automatically cuts against a merit-based approached?… Racism was once considered the good kind of inequality. The racial hierarchy… was a reflection of inherent merit. After all, how could whites be so much more powerful if they weren’t somehow better on the ontological level? Those for whom the race-based meritocracy was too crass leaned on the superiority of cultural institutions….

People demonize equality as totalitarian uniformity–hat would look different for different people, and I think it’s fair to say that such a life might contain its share of tedium and toil (rendered more bearable by its being shared and unstigmatized)…. But… it’s worth the effort of trying to figure out the elusive “what it would look like.”