This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth has published this week and the second is work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

The share of men with a job has been on the decline for decades in the United States. Most explanations for this trend focus on forces that affect men during their working years. But new research from Stanford University’s Raj Chetty and his co-workers highlights the influence of one’s boyhood environment on employment later in life.

The fourth report in Equitable Growth’s “History of Technology” series focuses on responsible innovation, a movement during the 1970s fighting for reforms to the research community in the United States. Cyrus Mody—the report’s author and a professor at Maastricht University—shows how those fights are relevant for thinking about innovative growth today.

Who pays a tax? The answer may not be as simple as whom the tax was placed upon. The incidence of a tax depends on how elastic the supply of and the demand for the good or service is. The example of a proposed oil tax may be illuminating.

The U.S. economy has a tale of two wage growth statistics going on right now. Nominal wage growth is subpar, but inflation-adjusted wage growth looks solid. Which statistic tells us more about the health of the labor market? Here’s an argument for focusing on nominal growth.

When a worker loses a job, they have to find a way to cushion the blow of losing their main source of income. Credit can help them bridge that gap. And increased access to credit can help them search for a higher-paying job than they would have found otherwise.

Yesterday marked the launch of “Equitable Growth in Conversation,” our new series of talks with economists and social scientists. The first installment is an interview with Larry Summers by Heather Boushey about secular stagnation and the role of economic inequality.

Links from around the web

The Great Recession has caused many rethinks in economics and spurred many research agendas. The role of fiscal policy in fighting recessions is an important example of shifting thinking in the wake of the recession. Adam Ozimek takes a look at what we’ve learned and what we still need to dig into. [datapoints]

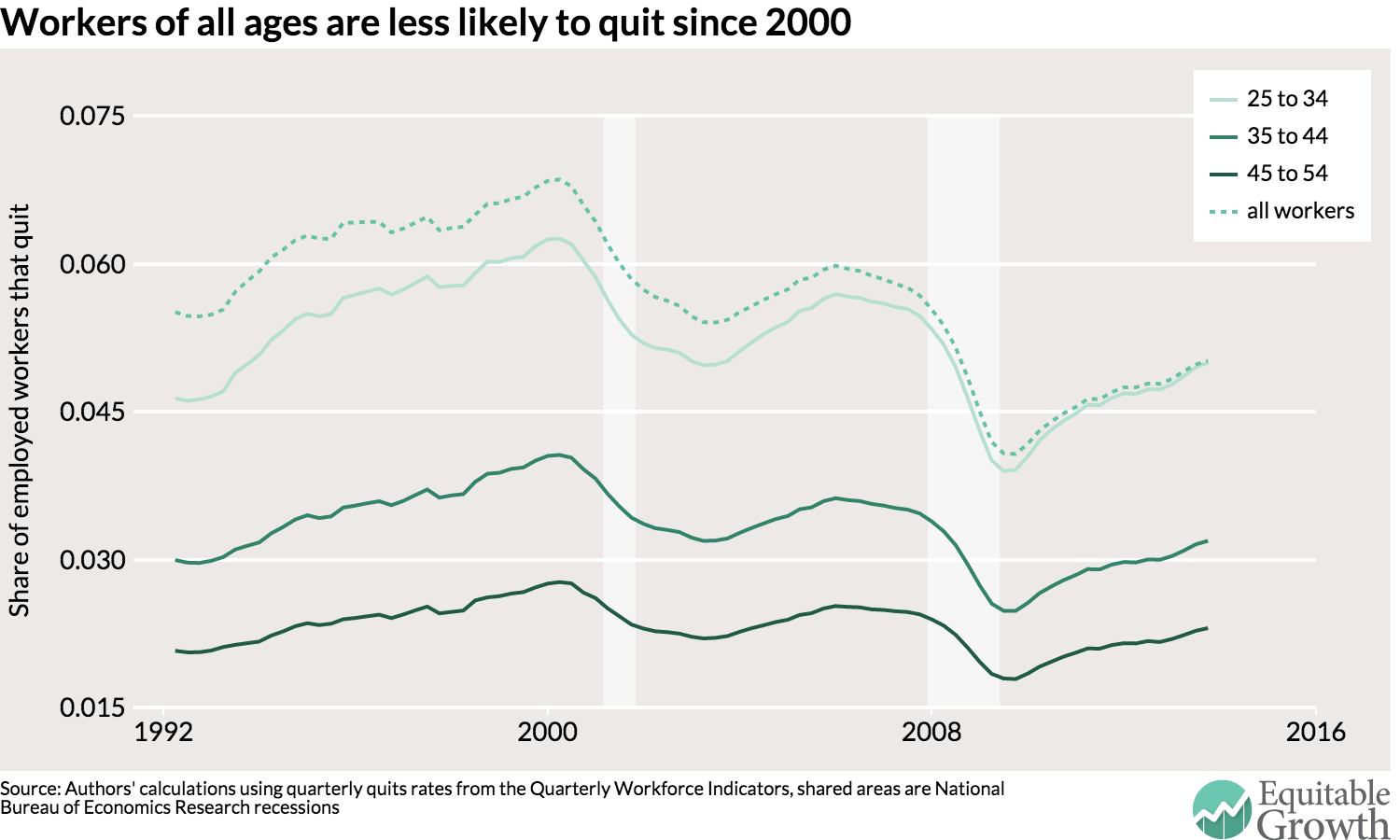

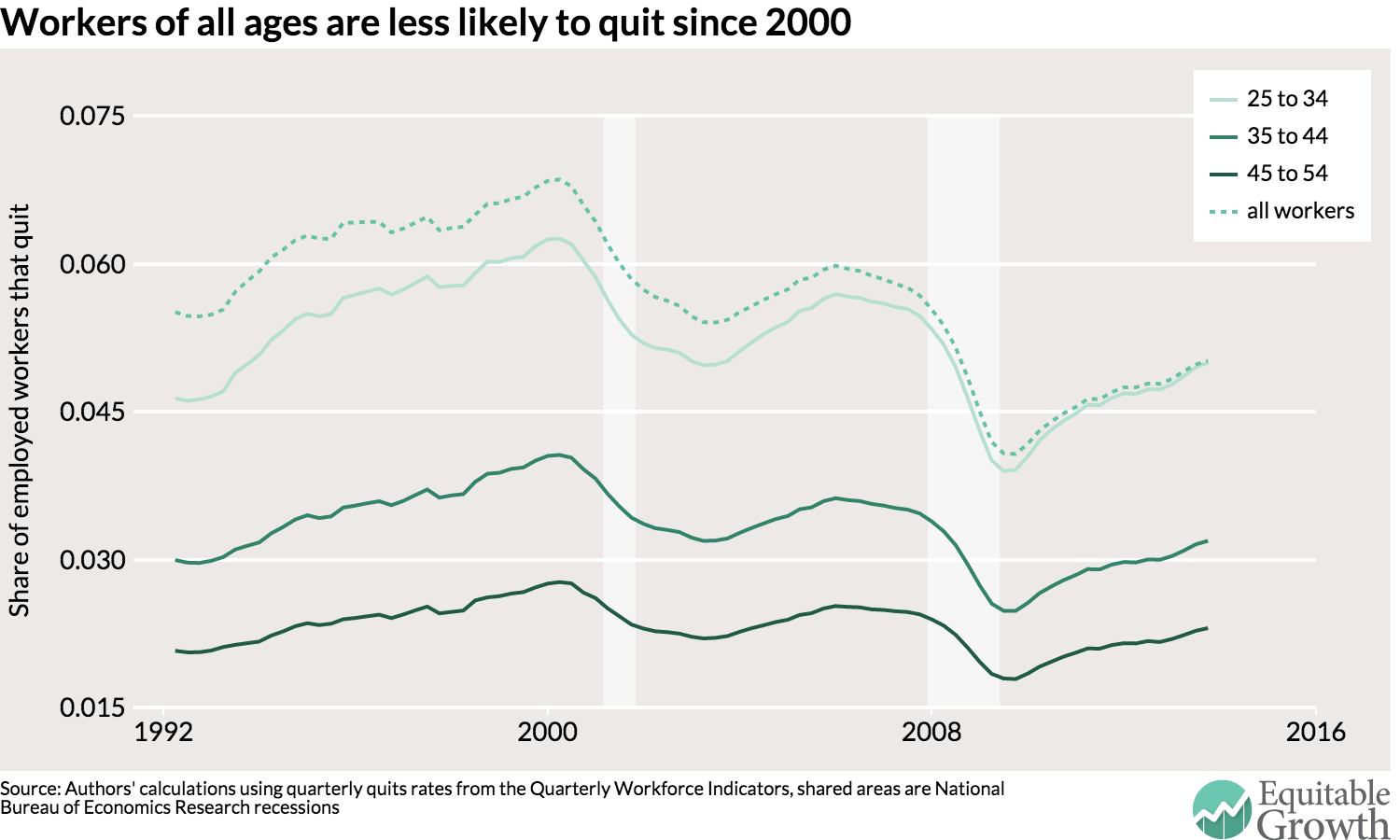

This week’s release of data about labor market flows in December sparked optimism about the U.S. labor market. Workers are seemingly quitting their jobs at rates not seen since before the Great Recession—a sign of a healthier labor market. But Dean Baker argues we shouldn’t be satisfied until the rate has exceeded its old peak for a while. [beat the press]

One of the criticisms of the idea that increasing housing supply can increase housing affordability is that the housing being built is just for high-income residents. But evidence from the Bay Area indicates that lower-income neighborhoods with more housing construction saw less displacement than similar neighborhoods with less construction. Emily Badger reports. [wonkblog]

Negative interest rates are weird, to say the least. The advent of this heretofore impossible situation has sparked some really big questions about the role of the financial system and even the definition of money. Neil Irwin takes a look at the world on the other side of the monetary looking glass. [the upshot]

Negative interest rates—now that we know they are possible—may be the answer to how to ease monetary policy in our current environment. Narayana Kocherlakota, former president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, argues they are appropriate right now. But their necessity is an indictment of fiscal policymakers. [thoughts on policy]

Friday figure

Figure from “Demographics don’t explain the decline in quitting” by Nick Bunker and Kavya Vaghul