This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is the work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope that by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Equitable Growth released a working paper looking at why displaced workers experience long-term earnings losses. Equitable Growth grantees Marta Lachowska and Stephen Woodbury, along with Alexandre Mas find that unemployed workers who find new jobs experience reduced earnings in the short term—explained almost entirely by lost work hours—and also over the long term even as they work more hours because they do not regain their prior wage levels.

Nisha Chikale digs into the key findings of Lachowska, Mas, and Woodbury—that hours and wages both contribute to earnings declines for displaced workers, but the types of firms where they eventually found jobs matters as well.

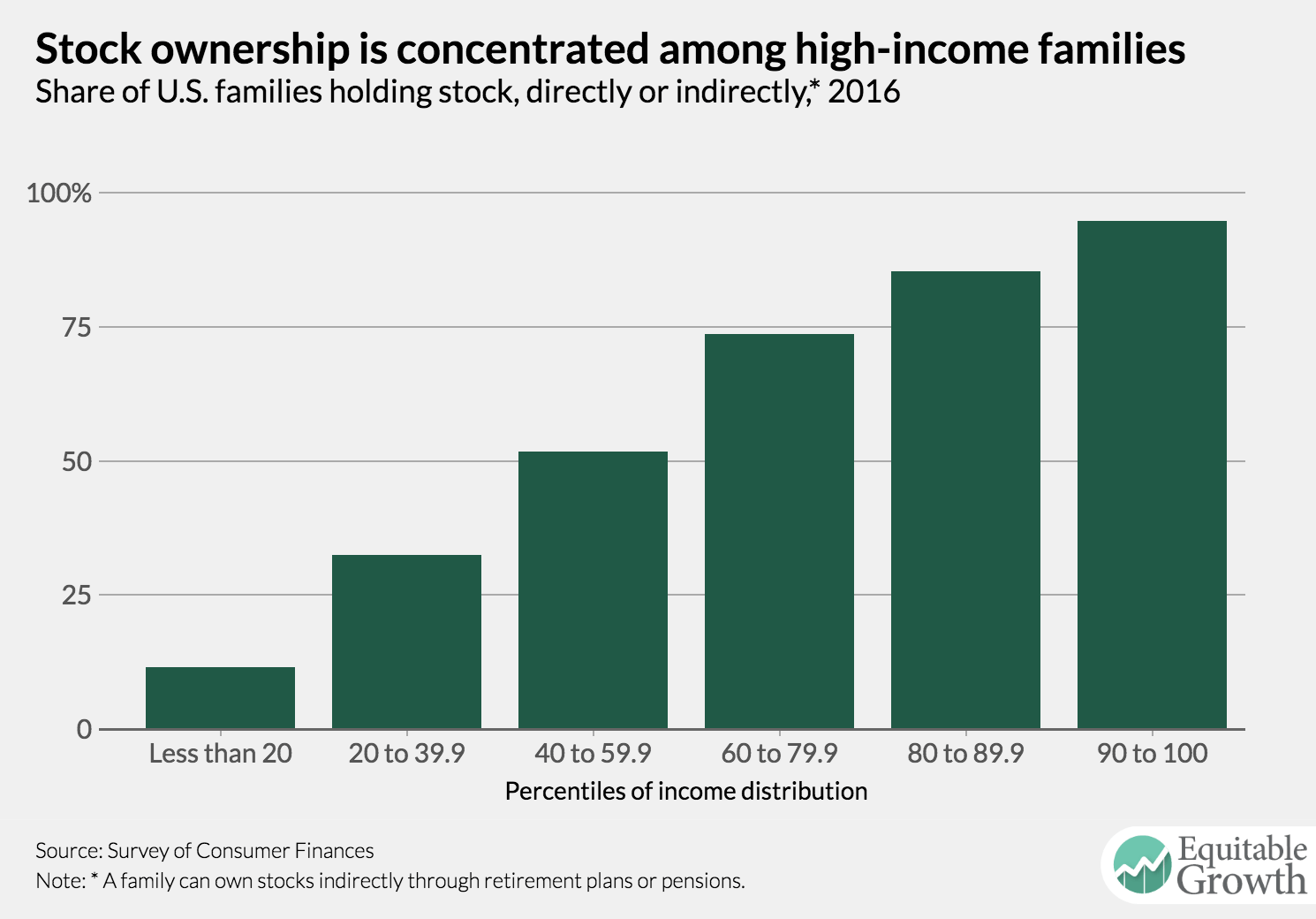

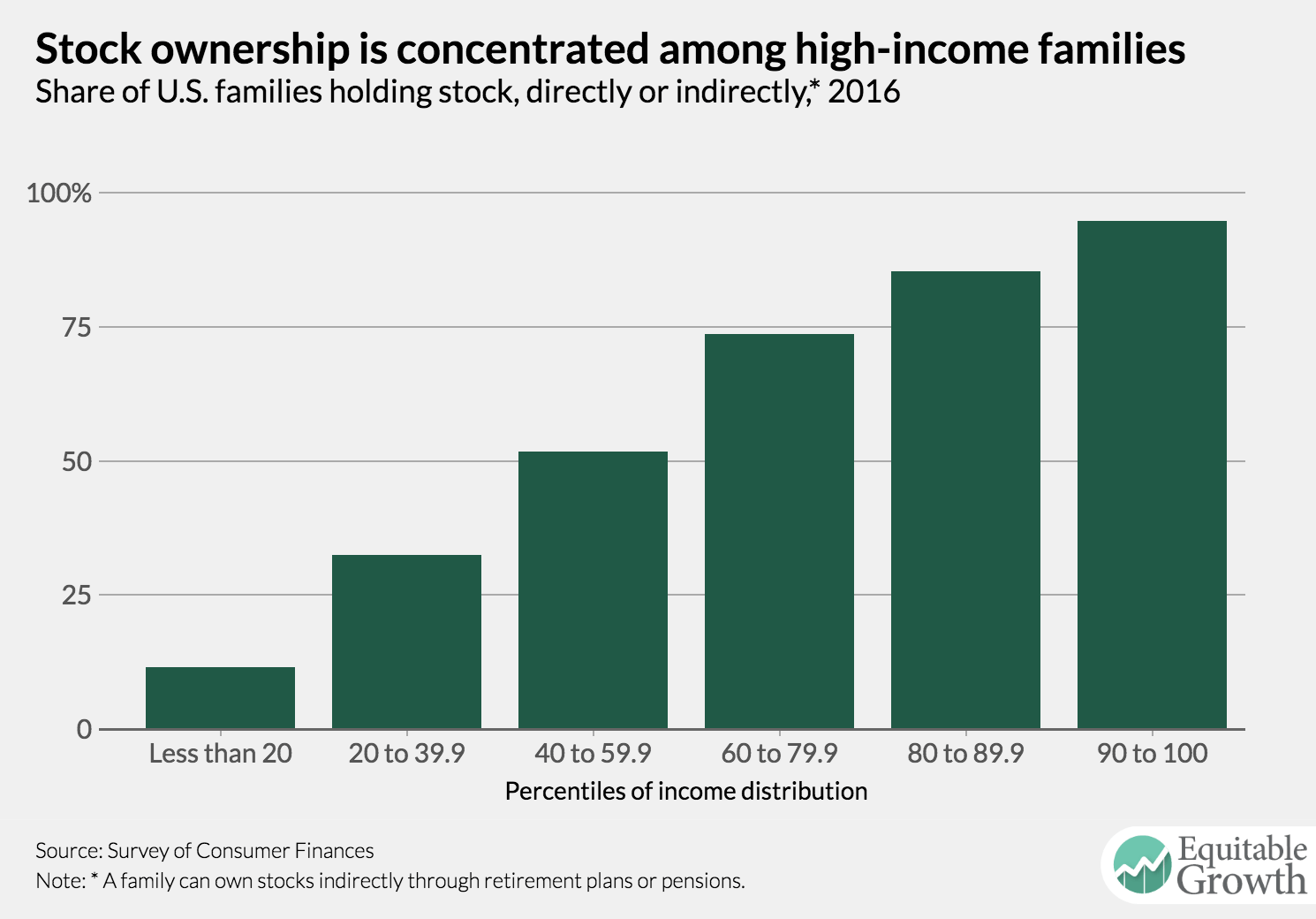

The U.S. stock market is on a roll, but what does this mean for the broader U.S. economy? Nick Bunker explains why, absent reforms to broaden stock ownership and to help reconnect business investment and profit growth, policymakers shouldn’t get overly excited about a booming stock market.

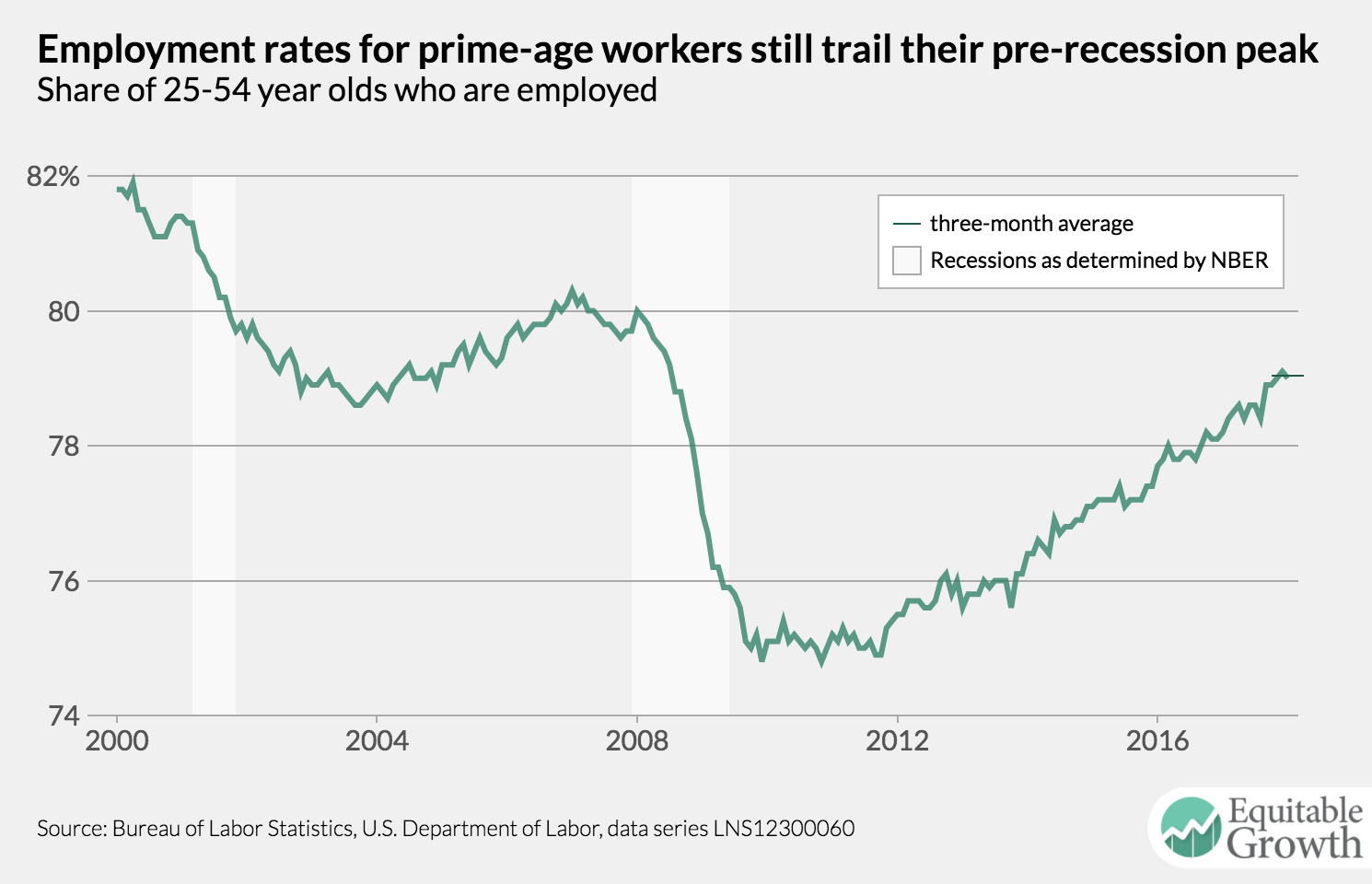

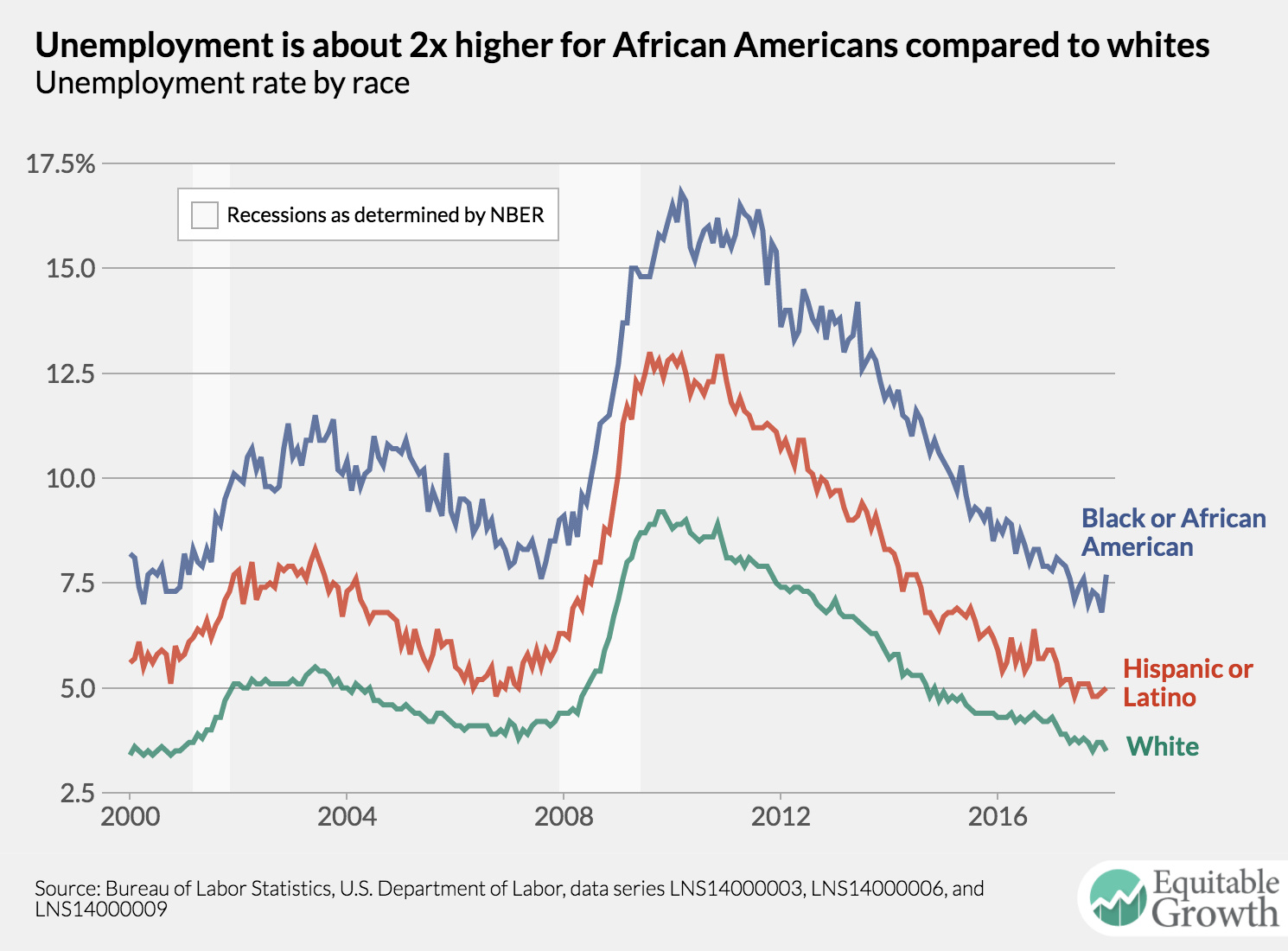

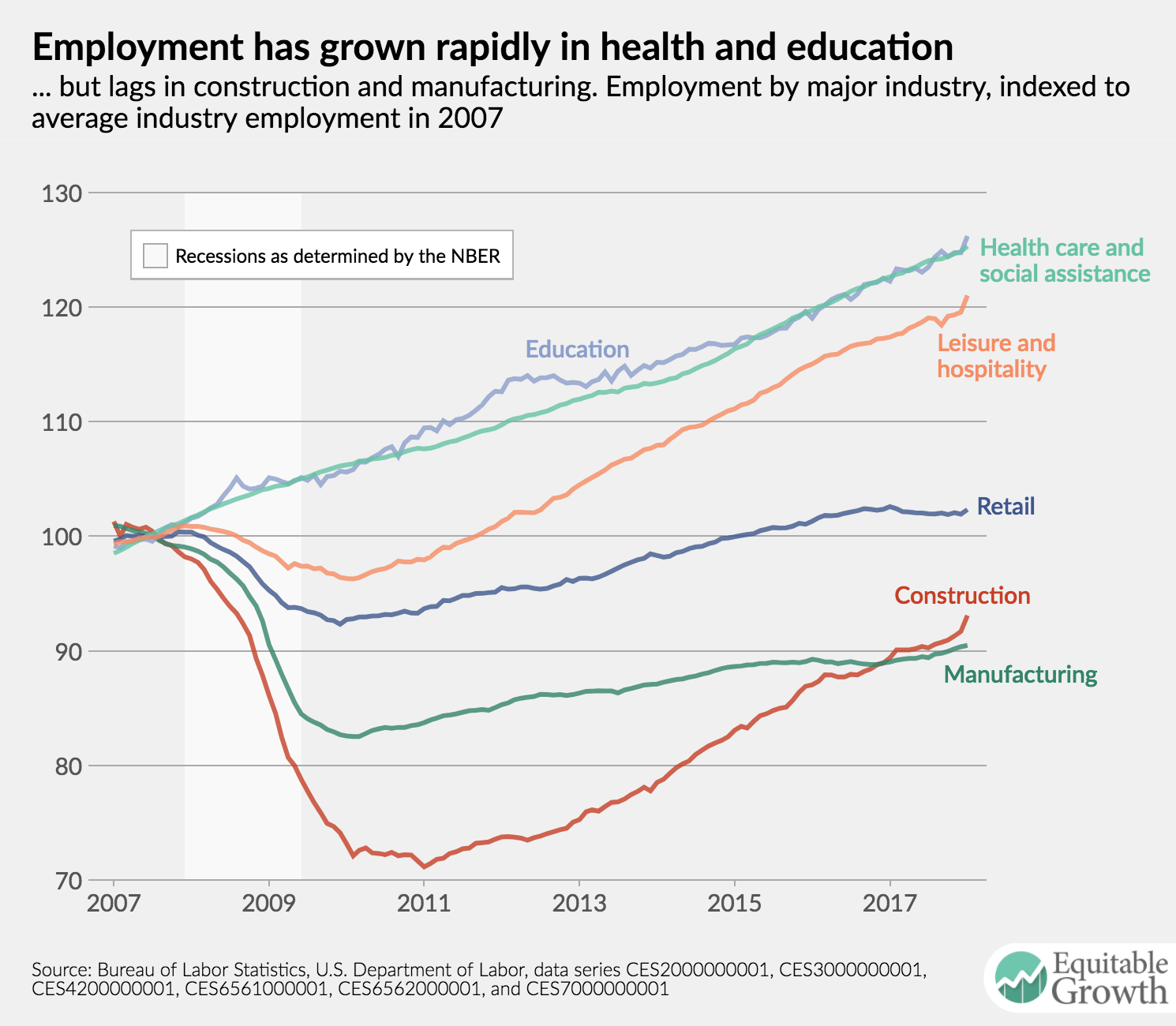

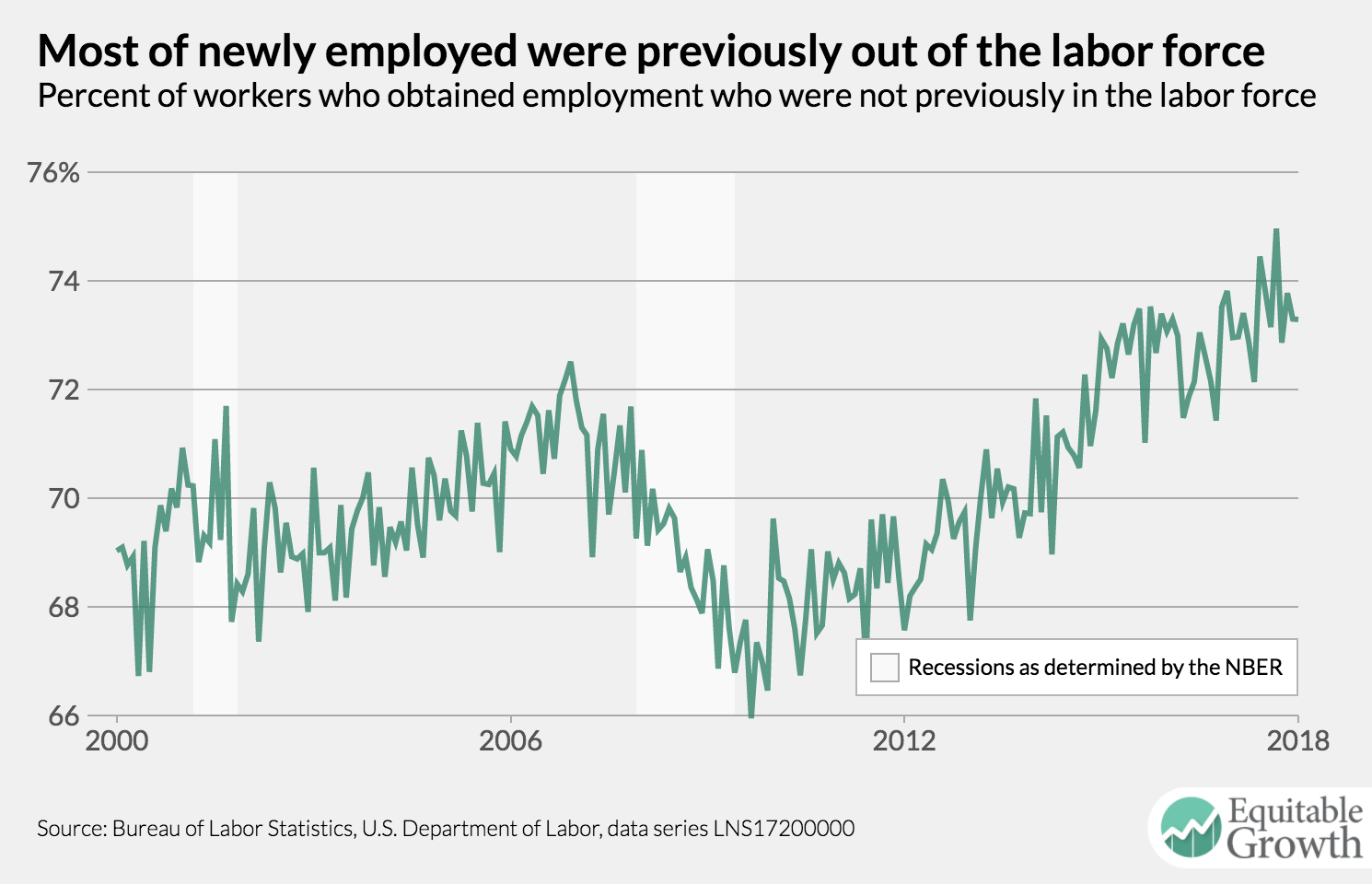

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released its latest U.S. labor market report for January this morning. Check out five key graphs from the new data compiled by Equitable Growth staff.

Links from around the web

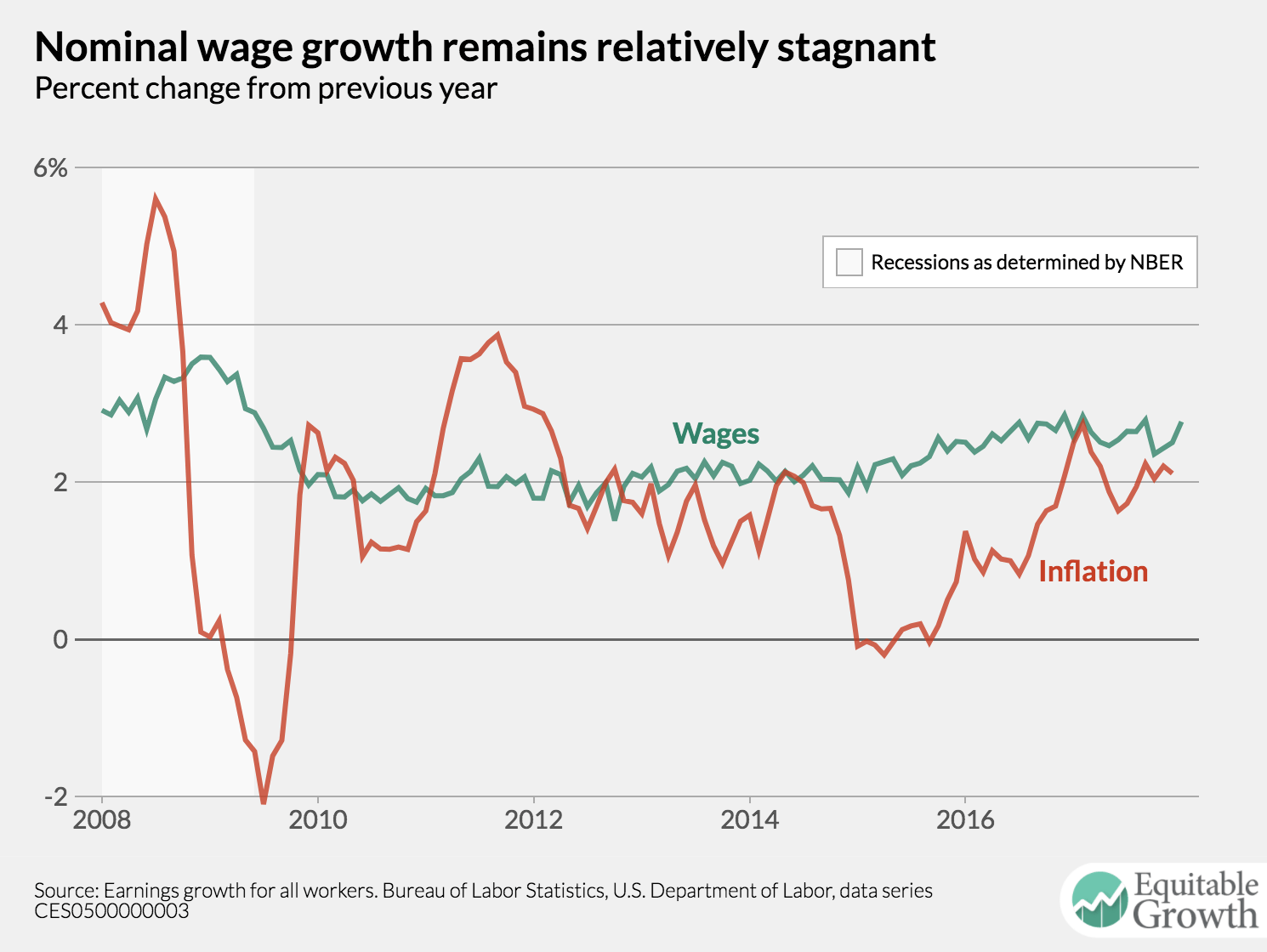

One of the major mysteries of the post-Great Recession economic recovery has been the lack of wage growth even amid declining unemployment. Ben Casselman explores economic trends such as declining unionization, restraints on competition, and a lagging minimum wage that may be suppressing wages. [the new york times]

For many struggling communities across the country, Amazon.com Inc. coming to town seems like a “rare and wonderful” opportunity. Cities and states have offered up huge tax breaks and other development incentives to woo the company’s second headquarters to their neighborhoods. But, as Alana Semuels writes, San Bernardino, which opened a massive Amazon distribution center in 2012, learned the hard way that “Amazon can exacerbate the economic problems that city leaders had hoped it would solve.” [the atlantic]

The U.S. Department of Labor announced this week that pay in the private sector is up 2.8 percent, the largest increase since 2015. As the labor market tightens, economists expects wages to continue rising. Yet due to increasing industry consolidation and market concentration, Kimberly Adams explains that “even a worker shortage may not be enough to push wages up quickly.” [marketplace]

The U.S. retail industry overall is floundering as bricks-and-mortar stores all across the United States have been forced to close their doors. Over the past five years, however, discount retail outlets have opened a new store every four-and-a-half hours, and now boast a collective market value of $28 billion. “Dollar General thrives where low-income families struggle,” explains the company’s chief executive, adding that “the economy is continuing to create more of our core customers.’” [the economist]

A former staple among South Florida retirees may be on its way out. Jaya Saxena explains that amid a declining U.S. middle class and rising inequality, early bird value meal specials may be headed for extinction. [eater]

Friday figure