Category: Equitablog

Must-Read: Justin Wolfers: Growth in Real Average Income for the Bottom 90 Percent

Must-Read: : Growth in Real Average Income for the Bottom 90 Percent:

Growth in Real Average Income for the Bottom 90 Percent: pic.twitter.com/90OUpUj8nJ

— Justin Wolfers (@JustinWolfers) May 19, 2016

I Continue to Fail to Understand Why the Federal Reserve’s Read of Optimal Monetary Policy Is so Different from Mine…

Does you think this looks like an economy where inflation is on an upward trend and interest rates are too low for macroeconomic balance?

Mohamed El-Erian says, accurately, that the Federal Reserve is much more likely than not to increase interest rates in June or July: : Federal Reserve Is Torn: “”Moves in financial conditions as a whole are making [the Fed]…

…more confident about going forward [with interest-rate hikes,] and they were worried that the markets were underestimating the possibility of a rate hike this year and they wanted to do something about it…. In the end, what’s clear is a hike will definitely happen this year…. If the Fed unambiguously signals that it will move, you will see a stronger dollar and that… will have consequences on other markets…

Olivier Blanchard (2016), [Blanchard, Cerutti, and Summers (2015)2, Kiley (2015), IMF (2013), and Ball and Mazumder (2011) all tell us this about the Phillips Curve:

- The best estimates of the Phillips Curve as it stood in the 1970s is that, back in the day, an unemployment rate 1%-point less than the NAIRU maintained for 1.5 years would raise the inflation rate by 1%-point, and that a 1%-point increase in inflation would raise future expected inflation by 0.8%-points.

- The best estimates of the Phillips as it stands today is that, here and now, an unemployment rate 1%-point less than the NAIRU maintained for 5 years would raise the inflation rate by 1%-point, and that a 1%-point increase in inflation would raise future expected inflation by 0.15%-points.

In only 6 of the last 36 months has the PCE core inflation rate exceeded 2.0%/year. I keep calling for someone to present me with any sort of optimal-control exercise that leads to the conclusion that it is appropriate for the Federal Reserve to be raising interest rights right now.

I keep hearing nothing but crickets…

My worries are compounded by the fact that the Federal Reserve appears to be working with an outmoded and probably wrong model of how monetary policy affects the rest of the world under floating exchange rates. The standard open-economy flexible-exchange rate models I was taught at the start of the 1980s said that contractionary monetary policy at home had an expansionary impact abroad: the dominant effect was to raise the value of the home currency and thus boost foreign countries’ levels of aggregate demand through the exports channel. But [Blanchard, Ostry, Ghosh, and Chamon (2015)][6] argue, convincingly, that that is more likely than not to be wrong: when the Fed or any other sovereign reserve currency-issuer with exorbitant privilege raises dollar interest rates, that drains risk-bearing capacity out of the rest of the world economy, and the resulting increase in interest-rate spreads puts more downward pressure on investment than there is upward pressure on exports.

It looks to me as though the Fed is thinking that its desire to appease those in the banking sector and elsewhere who think, for some reason, that more “normal” and higher interest rates now are desirable is not in conflict with its duty as global monetary hegemon in a world afflicted with slack demand. But it looks more likely than not that they are in fact in conflict.

[6]: Blanchard, Jonathan D. Ostry, Atish R. Ghosh, and Marcos Chamon

How high levels of inequality might change what innovation we see

When asked why he robbed banks, Willie Sutton reportedly replied, “Because that’s where the money is.” That dictum is apt for more than just bank robbery, though. If you’re running a business, it makes sense to target your efforts and products to large and growing markets. Perhaps that market is large because of the number of people in it or because of the amount of money the people in the market have. The rise of income inequality in the United States—an increase in the relative amount of money some people have—has made some researchers and analysts wonder if this change in potential markets affects innovation. Maybe the rise in inequality has spurred companies into innovating more for households at the top of the income distribution? Well, a new research paper finds such a result.

The new research comes from a working paper from Harvard University Ph.D. student Xavier Jaravel. The intent of the paper is to look at who has gained the most from the innovations in consumer products from 2004 to 2013. As Jaravel points out, if product innovation has focused more on consumers at the top of the income ladder, then prices will probably end up being lower.

Jaravel got access to scanner data that gives him access not only to data on the prices of goods that individuals buy but also to information about their quality and the incomes of the consumer. What he ends up finding is this: As incomes increased at the top (above $100,000 a year to be exact), more consumer goods targeted toward those consumers entered the market. This increase in the supply of goods ended up driving down the price of these goods. (For those concerned about which way causality is flowing here, Jaravel offers two statistical tests to tease out the causal effect of increases in market size on product innovation and finds that his findings hold in both cases.)

The impact of these price drops is fairly significant. Jaravel finds that the average annual inflation rate over the time period studied for households making more than $100,000 a year was 0.65 percentage points lower than that for those making less than $30,000. As inflation rates go, that’s a fairly significant difference. Over a five-year period, that’s about a 3-percentage-point difference in cumulative inflation.

This finding also has relevance for the amount of inflation-adjusting income inequality in the United States. If products have become relatively cheap for households at the top, then their incomes have actually grown even more than we thought. In other words, inequality has increased more than we previously thought based on research that assumes that all households, rich and poor, face the same inflation rate.

More intriguingly still, if Jaravel’s findings hold up and hold to areas outside of consumer goods, then it means inequality may well shape the path of innovation. Many economists are concerned about the pace of innovation, but maybe we should all be thinking about the beneficiaries of innovation. Sure, innovation may trickle down in some cases (think cell phones), but maybe we might want to see some innovation focused right from the beginning on pressing issues facing a broad swath of the population. What good are cheaper consumer goods if they’re only for a select few?

(featured photo credit: iStock/Anatoly Vartanov)

The new overtime rule is “good economics and good business”

Millions of Americans may soon be getting a raise, or at least will gain more time away from the office after a standard 40-hour workweek. The Department of Labor is set to issue a final ruling to expand the Fair Labor Standard Act’s overtime coverage today, making salaried workers earning up to $47,476 a year eligible for time-and-a-half pay if they work beyond a 40-hour week. The Obama Administration estimates that the new regulations, which go into effect on December 1st, will extend overtime protections to more than 4 million workers (with others estimating more).

The ruling is the first substantial update to the threshold since 1975, which covered 62 percent of salaried employees at the time. But because the overtime rule was not tied to inflation, today’s current threshold of $23,660 is below the poverty line for a family of four and covers only 7 percent of the salaried workforce. The updated provision allows for future increases every three years.

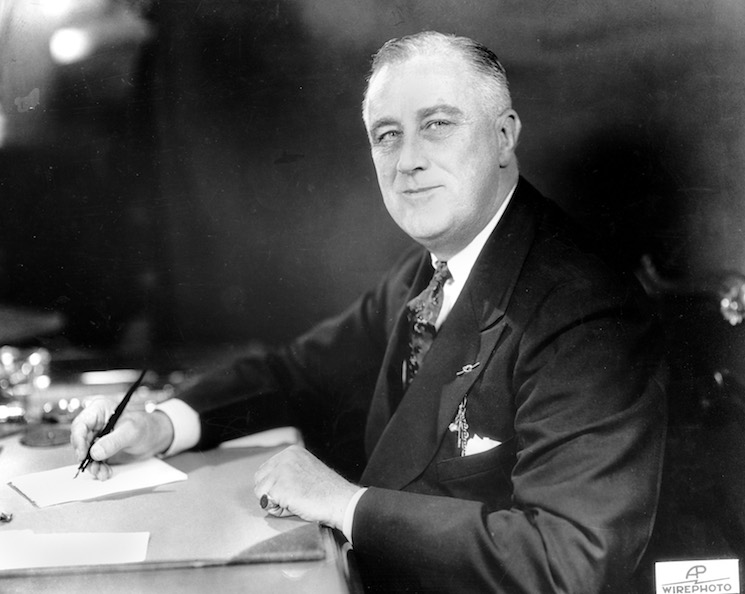

The new rule will obviously help individual workers, but these work-hour protections also deliver significant benefits for the entire economy as well. When the Fair Labor Standards Act was first enacted in 1938 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the height of the Great Depression, champions of the overtime provision argued that it would not just mitigate overwork but also encourage employers to “spread the work” by hiring more people working fewer hours. Roosevelt also urged businesses concerned about the initial cost of hiring more workers to consider that increasing employment would indirectly inject some much-needed cash into the struggling economy. As Roosevelt said in 1933:

I ask that managements give first consideration to the improvement of operating figures by greatly increased sales to be expected from the rising purchasing power of the public. That is good economics and good business. The aim of this whole effort is to restore our rich domestic market by raising its vast consuming capacity.

Today’s economy differs from that of the 1930s, yet, in an economy that is not operating at full capacity, this policy is likely to put more money into workers’ pockets. A bigger paycheck boosts their ability to buy goods and services—a key economic engine for domestic growth. That is because workers that will benefit from these policies are more likely to spend the extra money they earn.

Even if employers respond to the new overtime rules by limiting hours, which has been cited as a criticism of the new regulations, the extra time workers gain—time spent investing in one’s health, education, community, or family– may be just as valuable to some workers. Exhaustion from overwork takes a detrimental toll on one’s mental and physical health, relationship, or even one’s children. That may be why, when University of Pennsylvania, Abington’s Lonnie Golden undertook a 2013 survey of 1,000 adults, he found that one in five workers would take a 20 percent pay cut in exchange for one fewer day of work.

Because there are a certain number of fixed costs associated with each individual employee, it may seem like a cost-effective business strategy to have fewer employees work longer hours, especially if an employer does not have to pay them overtime. But Stanford University’s John Pencavel finds that, generally speaking, a worker’s output drops sharply if they routinely work beyond 49 hours a week (even if you think you are getting a lot done). If you tend to stick around the office late at night on a routine basis, you are getting little work done at the expense of your own well-being.

This costs companies money. One study contends that in 2007, fatigued workers cost employers more than $100 billion annually in lost productivity. Overtime also raises the rate of mistakes and safety mishaps, which put the general public at risk. Federal regulators, for example, found that a truck driver’s extreme fatigue due to many hours on the road was the main causes in the crash that killed comedian James McNair and critically injured Tracy Morgan.

More standardized work hours also make it easier for those with outside obligations to navigate the demands of work and life, which has implications on a national scale: When employers require long hours, it means they are less likely to hire those with caregiving or other outside responsibilities. Because women still take on the bulk of the caregiving responsibilities, long hours may push some women out of the workforce. This doesn’t just harm female workers: Because women are graduating from college and graduate school in higher numbers than men, employers miss out on the opportunity to hire the most qualified people for the job.

Fewer women in the labor market also harms the economy as a whole. Research by Equitable Growth’s Heather Boushey and John Schmitt, and Eileen Appelbaum at the Center for Economic and Policy Research found that that U.S. gross domestic product would have been about 11 percent lower in 2012 if women had not increased their working hours as they did since 1979. That translates to $1.7 trillion less in output—similar to what the combined U.S. spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid in 2012.

There is no doubt that workers and their families cannot succeed without hard work. But we must be more mindful of the consequences for individuals, businesses, and the economy alike associated with working without limitations. The new overtime rule, which will disproportionately help women, workers under 35, African Americans, Hispanics, and workers with lower educations, is an important step.

Must-read: Ben Thompson: “China Watching”

Must-Read: : China Watching: “I am often asked why I don’t write more about China…

…the reason, as I’ve explained in the past, is that the country, particularly anything having to do with the government–which by extension covers all big businesses, tech included–is basically unknowable to an outsider, and the more you learn about China, the more you realize this is the case. To that end, while I feel relatively confident about what I am going to write, given the Chinese angle I am unashamed to admit that I could be 100% wrong; frustratingly, we will probably never know for sure…

Must-read: Marshall Steinbaum: “Uber’s Antitrust Problem”

Must-Read: Are Uber and companies like it anti-rent seeking plays? Yes. Are they regulatory arbitrage plays? Yes. Are they behavioral economics plays–exploiting their workers who don’t properly calculate depreciation? Plausibly. What’s the proper balance? Allowing Uber to claim that its workers are in no sense its employees is surely wrong. Shielding existing rent-seeking monopolies created by regulatory capture from competition from Uber and its ilk is also surely wrong:

: Uber’s Antitrust Problem: “The Uber lawsuit captures the key question facing policymakers struggling to regulate the ‘gig’ and ‘platform’ economies…

…Are the new behemoths of the tech sector innovators that make the economy more efficient by ‘disrupting’ antiquated business models? Or are they just the trusts of a second Gilded Age, their new-fangled apps the equivalent of the railroad networks that monopolized commerce and access to markets 126 years ago, when the Sherman Act first took effect?

Until now, Uber and its fellow tech giants have managed to mystify policymakers and judges with double-speak regarding their relationship with employees. But in his decision allowing the case to move forward, Judge Rakoff wrote: ‘The advancement of technological means for the orchestration of large-scale price-fixing conspiracies need not leave antitrust law behind.’ Now one court has the chance to decide whether Uber can continue to have it both ways.

Must-reads: May 18, 2016

- : Apple in China

- : A General Theory of Austerity

- : Macro and Other Market Musings: The United States as a Banker to the World

- : Economic Models Must Account for ‘Who Has the Power’

- : The Fed’s Pause and the Dollar’s Retreat

- : What’s your (sur)name? Intergenerational mobility over six centuries

- : The Facebook Papers: Part 1: The great unbundling | The user experience revolt

- Today’s Economic History: John Maynard Keynes (1919): To Jan Smuts: ‘Ruthless Truth-Telling’

Must-Read: Ben Thompson: Apple in China

Must-Read: : Apple in China: “Apple… with its model of status-delivering hardware differentiated by software locked to its devices…

…has been uniquely successful in the world’s most populous country. [And] for many years Apple’s model freed them from the usual hoops that most Western tech companies have had to jump through to get a piece of the irresistible Chinese market. For example:

- Microsoft spends $500 million a year in China, mostly at its Beijing R&D center (its largest outside of Redmond), and has promised to up that total after a recent antitrust investigation

- Cisco pledged to invest $10 billion in China last year after being increasingly frozen out from Chinese purchases after the Edward Snowden revelations

Qualcomm, after settling an antitrust case, formed a $280 million joint venture with a provincial government that included technology transfer- Intel has promised up to $5.5 billion to transform a chip plant that it originally said would be two generations behind to become cutting edge; a few months later the company formed a joint venture with two local firms in direct response to Chinese concern about reliance on foreign companies in the chip industry. That follows a previous $1.5 billion investment in two other chipmakers partially owned by the Chinese government

- Dell adopted a new strategy last fall predicated on partnering in China to the tune of $125 billion over five years, forming a joint venture with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and deep partnerships with Kingsoft Corporation for work in the cloud ‘fully supporting and embracing the China ‘Internet+’ national strategy.’

The Internet+ strategy is a plan to integrate the Internet with traditional industries, but its introduction has gone hand-in-hand with an increasingly strong preference for Chinese technology from Chinese firms. Thus the partnerships, joint ventures, and investment. And yet, until now, the most successful American tech company in China has operated mostly without interference…

Today’s Economic History: John Maynard Keynes (1919): “I personally despair of results from anything except violent and ruthless truth-telling…”

Today’s Economic History: (1919): To Jan Smuts: “Ruthless Truth-Telling”: “My book [The Economic Consequences of the Peace] is completed and will be issued in a fortnight’s time…

…I am now so saturated with it that I am quite unable to make any judgement on its contents. But the general condition of Europe at this moment seems to demand some attempt at an éclairecissement of the situation created by the Treaty [of Versailles ending World War I], even more than when I first sat down to write. We are faced not only by the isolation policy of the U.S., but also by a very similar tendency in this country. There is a growing an intelligible disposition to withdraw (like America), so far as we can, from the complexity, the expense, and the unintelligibility of the European problems: and particularly as regards financial assistance, the Treasury is inclined, partly as a result of our own financial difficulties and partly because of the hopelessness of doing anything effective in the absence of American help, to let Europe stew. Also anti-German feeling here is, still, stronger than I should have expected. But perhaps most alarming is the lethargy of the European people themselves. They seem to have no plan; they take hardly any steps to help themselves; and even their appeals appear half-hearted. It looks as though we were in for a slow steady deterioration of the general conditions of human life, rather than for any sudden upheaval or catastrophe. But one can’t tell.

Anyhow, attempts to humour or placate Americans or anyone else seem quite futile, and I personally despair of results from anything except violent and ruthless truth-telling–that will work in the end, even if slowly…