This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is the work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Underemployment for recent U.S. college graduates was a very prevalent phenomenon in the wake of the Great Recession. But while it was a temporary for most grads, the trend raises some concerns about long-term trends in the U.S. labor market.

The issue of time spent outside of the (paid) workplace tends to be overlooked in debates around gender equality, but what happens at home has ripple effects throughout society, writes Bridget Ansel.

How much should policymakers tax capital? It’s a difficult question with lots of considerations we have to take into account before answering. A new paper provides a new framework for thinking about the optimal rate for U.S. capital taxation.

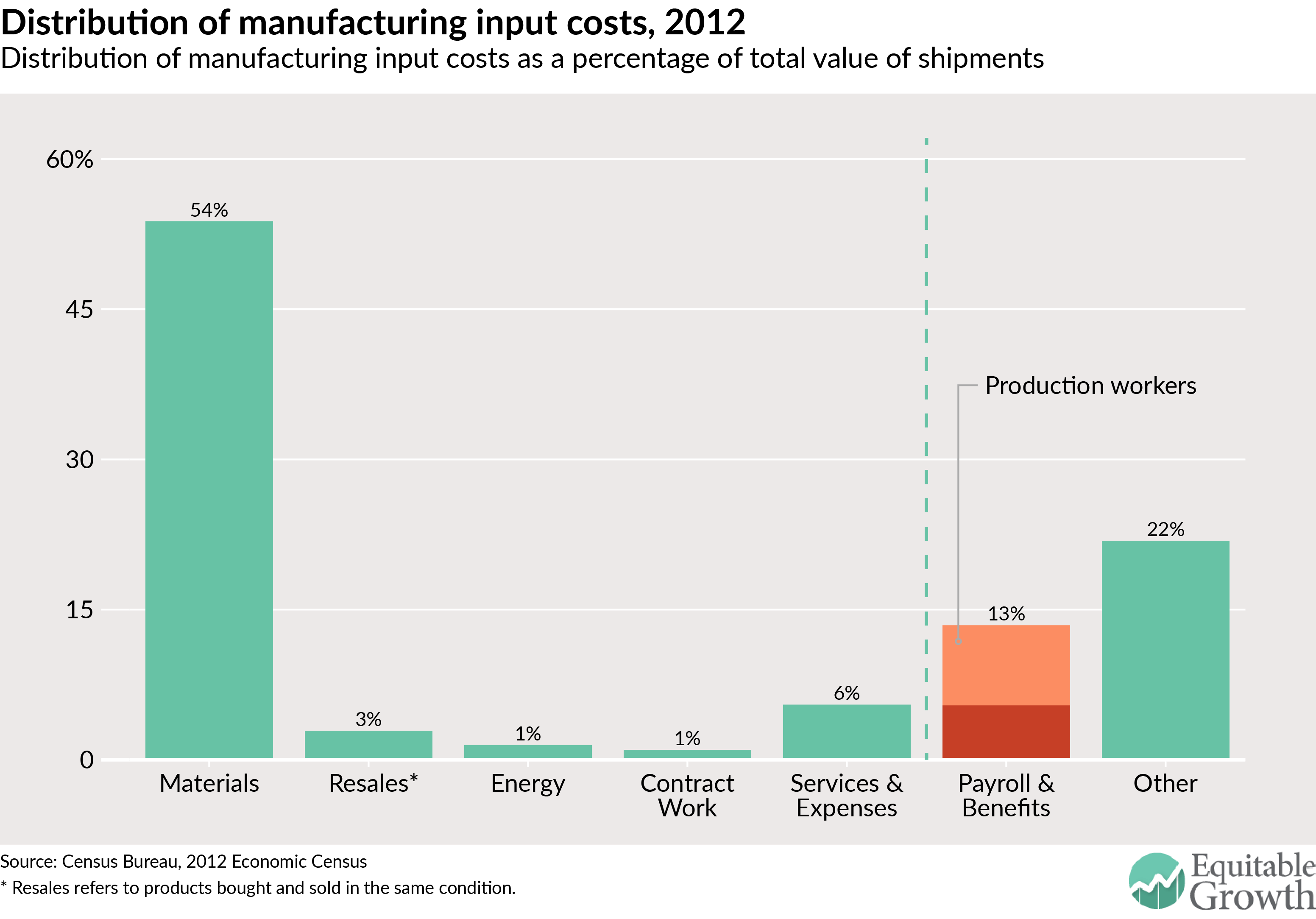

U.S. firms are increasingly outsourcing parts of their work to other firms. The growth of these supply chains is an underappreciated change in the U.S. economy and could have important implications for U.S. competitiveness and standards of living, according to a new report from Susan Helper and Timothy Krueger.

Would moving workers around the United States to maximize their chance of hiring significantly reduce unemployment? A new paper argues that, while it would have an impact, eliminating geographic mismatch in the U.S. labor market wouldn’t have a major impact on unemployment.

Links from around the web

One potential channel through which high levels inequality might affect economic growth is through reducing consumption. Larry Summers writes up a new International Monetary Fund working paper that shows a significant decline in consumption caused by higher inequality. [wonkblog]

A popular hypothesis for why productivity is on the decline is the shift away from manufacturing to the service sector in the United States? But maybe the service sector isn’t so much less productive than the manufacturing sector. Dietz Vollrath explains. [growth economics]

The U.S. population is aging and many workers are now entering the period of their working career when they won’t see much wage or earnings growth. This demographic shift can help explain the decline in overall U.S. wage growth, according to Robert Rich, Joseph Tracy, and Ellen Fu. [liberty street economics]

“To burst the illusion of safety in a particular financial asset is akin to shrinking the institutional money supply. But that is a tradeoff now considered worthwhile by regulators, a necessary price to pay for a stabler financial sector.” Cardiff Garcia writes on money market funds and financial regulation. [ft alphaville]

Long-run inflation expectations have been on the decline since 2014, around the time oil prices started to drop. Does this oil price trend explain all of the lower inflation expectations? Carola Binder describes her research pointing to additional reasons. [quantitative ease]

Friday figure

Figure from “Supply chains and equitable growth” by Susan Helper and Timothy Krueger