This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is the work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

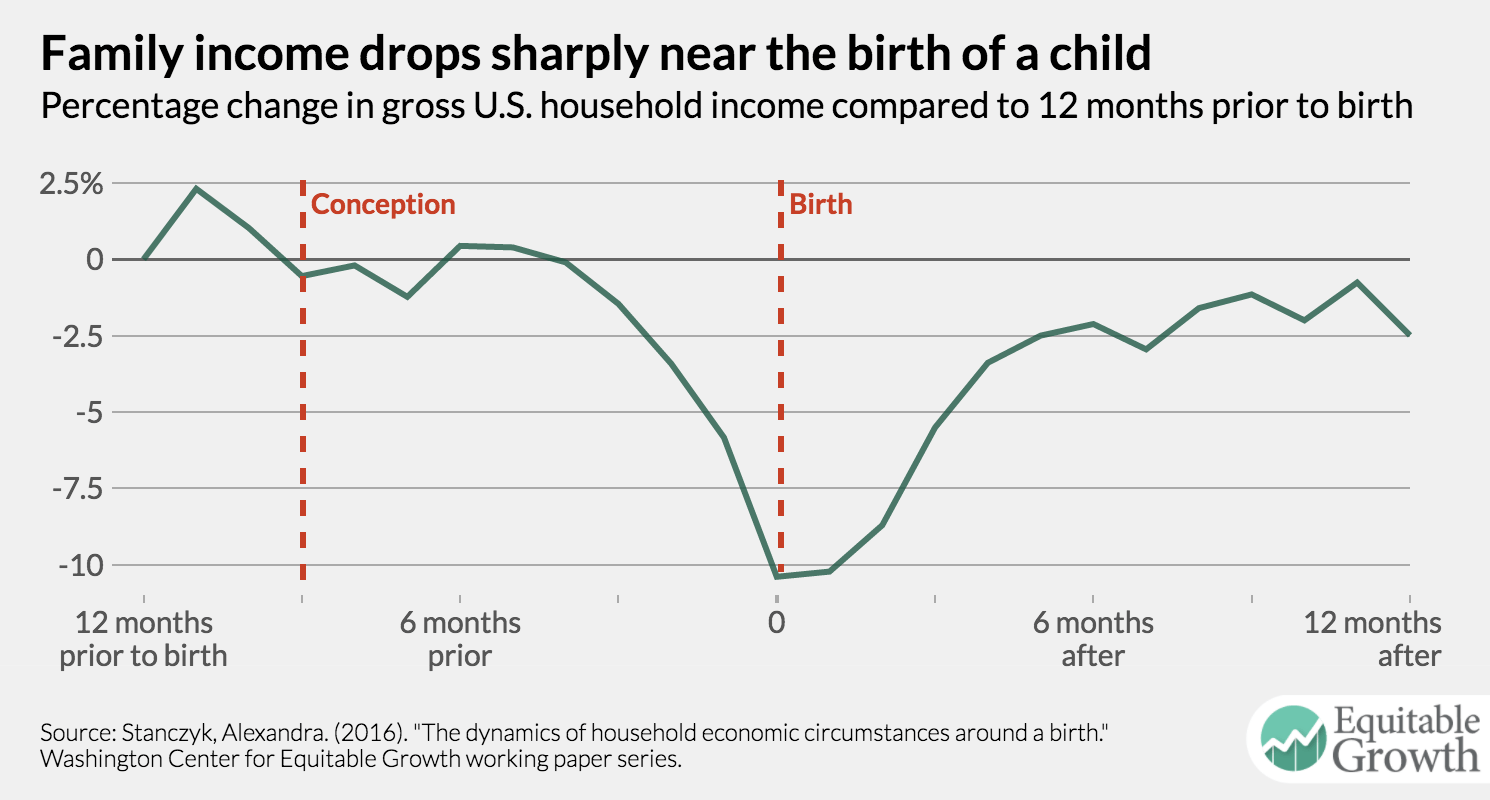

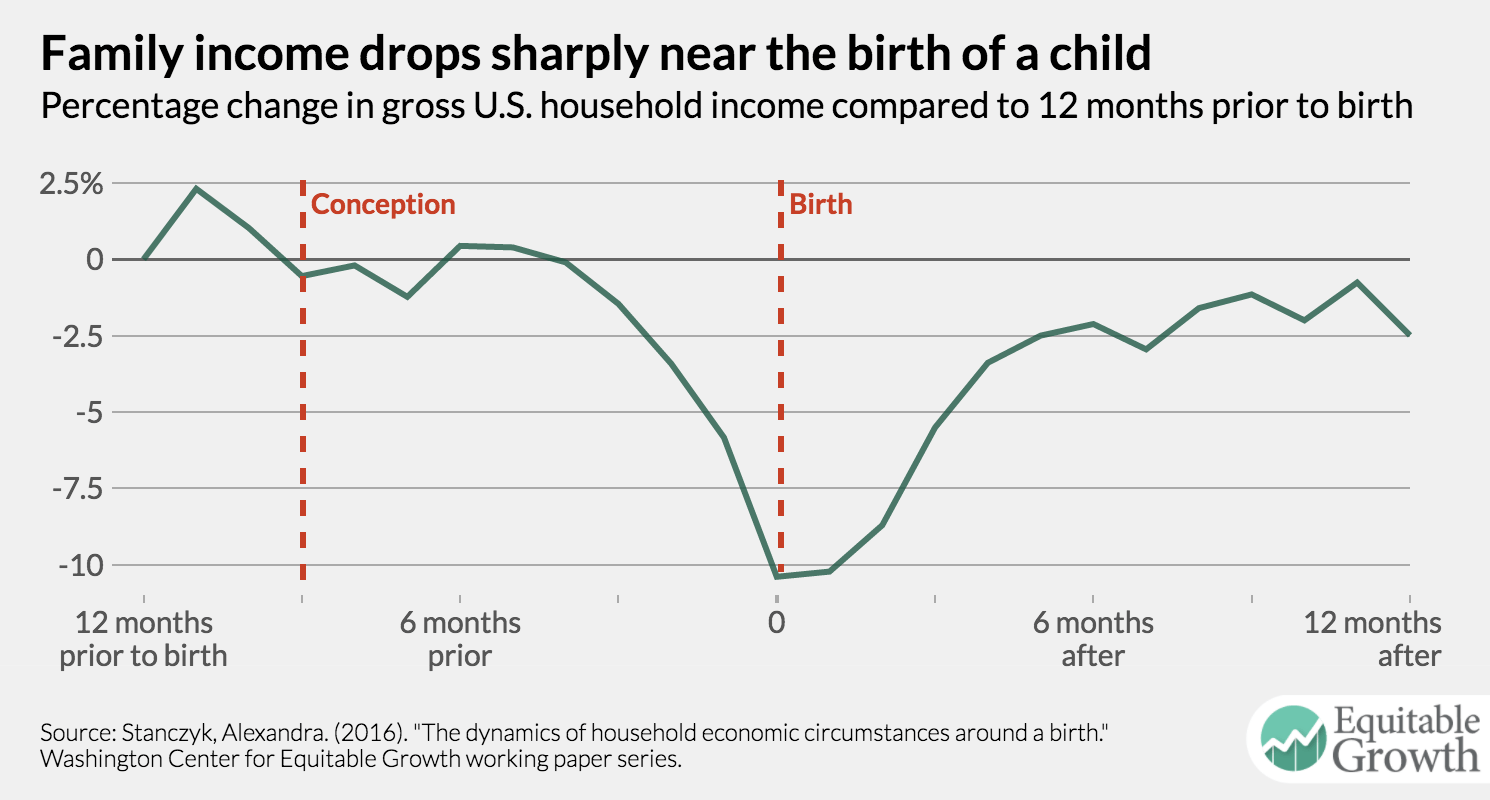

Despite the well-understood temporal and pecuniary chaos that is pregnancy and early parenthood, there is relatively little quantitative documentation on just how much a new child affects household finances in the Unied States. But new research provides new data on this front that Kavya Vaghul and Austin Clemens present with a number of graphs.

Last week, Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen gave a speech on the state of macroeconomics research in the wake of the Great Recession. The questions she posed are important, and investigations into those areas would be very worthwhile.

How much do U.S. workers value a choice in their work schedules especially when it comes to flexibility? Bridget Ansel digs into recent research on this questions and highlights the variation among the results.

Research on cash transfer programs in the United States focus, for the most part, on the effects of the program in the short run. But a new paper takes a look at the long-run effects on both parents and children. The paper can inform our understanding of the effect of different kinds of cash transfer programs.

Links from around the web

Is radically cutting the corporate income tax the best way to boost a flagging economy? Alana Semuels takes a look at the experience of Ireland and the United Kingdom to see if such a policy would be beneficial for the United States. [the atlantic]

The state of the federal budget deficit was brought up several times during the presidential debates this fall. But it’s not entirely clear that the deficit is an urgent or pressing policy concern right now. Richard Rubin and Nick Timiraos take a look at the level of concern among experts. [wsj]

A common narrative about U.S. manufacturing is that the sector is doing well because productivity growth is strong, leading to declining employment. But research by economist Susan Houseman of the Upjohn Institute challenges that story. Jared Bernstein interviews her about this work. [on the economy]

The homeownership rate in the United States has been on the decline since the peak of the housing bubble in 2006. Will this trend continue apace or will the rate level off or even climb? Timothy Taylor reviews a few projections. [conversable economist]

A recent survey finds about a quarter of Americans don’t trust official U.S. economic data. Why is that? Claudia Sahm runs through a number of hypotheses for why so many people don’t believe data from the federal government. [claudiasahm]

Friday figure

Figure from “Economic insecurity rises around childbirth, explained in four charts” by Kavya Vaghul and Austin Clemens